On November 7, 2019, news broke that 8 children aged 12-17 were killed in a military raid conducted by the Colombian military in late September. This newest violation of human rights added fuel to the mounting discontent against Colombia’s President Iván Duque and his cabinet members. This revelation came in the midst of an ongoing campaign for a historic paro nacional (national strike) scheduled for November 21, 2019, whose grievances include a host of issues: Duque’s proposed labor and pension reforms, privatization of electric and gas companies, instances of government corruption, including the Odebrecht scandal, cuts to education, a lack of progress on the historic 2016 peace accords, and a call for the government to do a better job at protecting social leaders who have been systematically threatened and assassinated for their work on social and economic justice initiatives since the signing of those same accords.

All of these claims and grievances can be encompassed into a concept known as positive peace, which includes not only the absence of direct violence by armed actors (including the state), but also takes into account issues of structural violence. Structural violence includes lack of access to food, potable water, shelter, medical care, and education, and should take into consideration the ways in which structural violence is compounded by intersectional identities. Intersectionality theory discusses the ways in which issues of both direct and structural violence is more likely to impact, or impacts more seriously, people who hold one or multiple minority identities.

This article discusses the relationship between Colombia’s historic, ongoing protests and these concepts of structural violence and positive peace as they relate to the 2016 peace accords. My research examines these concepts in the lack of implementation of the accords, and explores alternative forms of peacebuilding and implementation of transitional justice (TJ) mechanisms in areas where there is a lack of positive state presence. The explainers in this article are based on 60 semi-structured interviews conducted throughout Colombia between 2017 and 2019 (the first three years of the implementation of the accords), as well as my ongoing research.

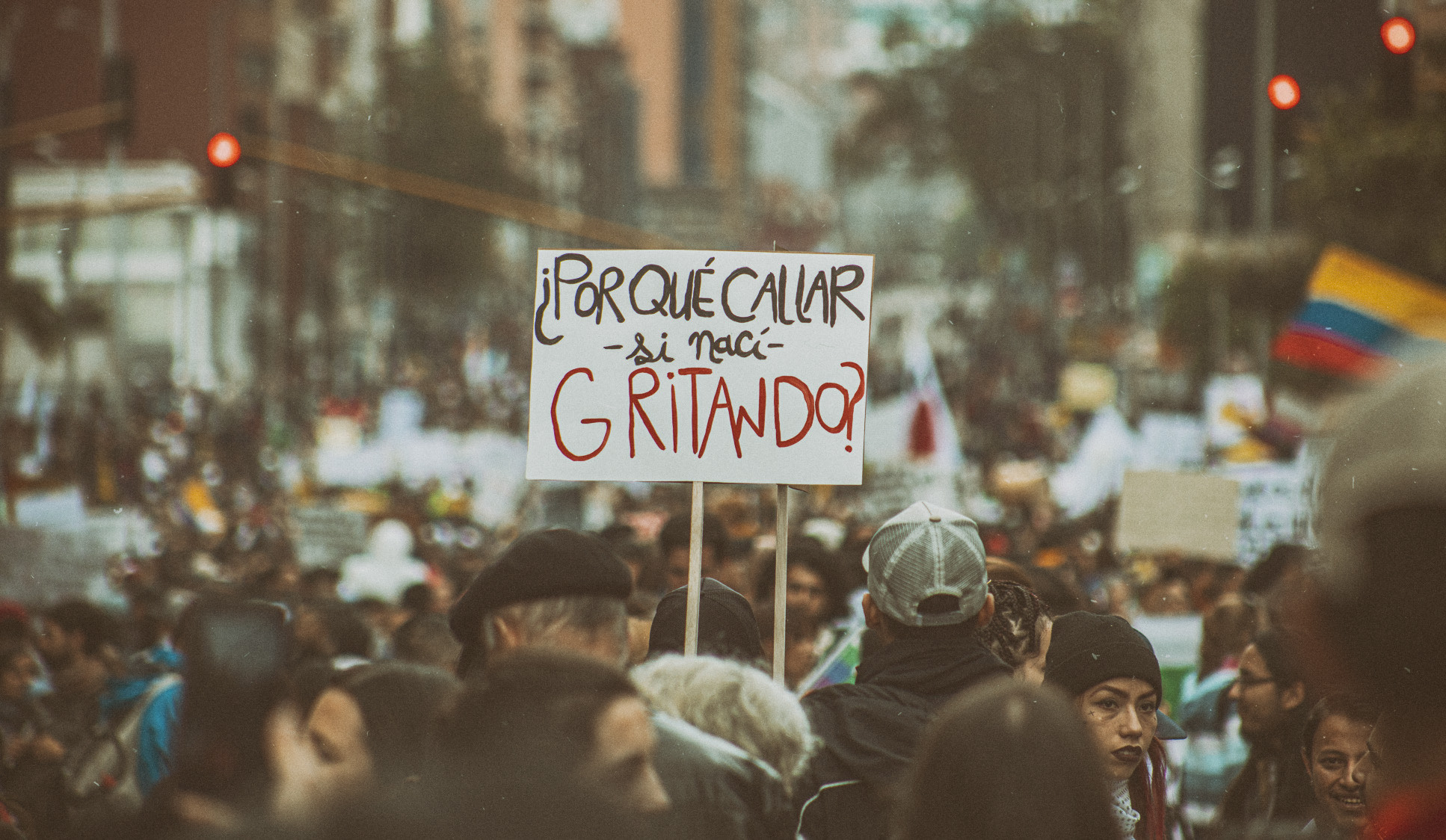

The following images (and the featured image) are by Alejandro Calderón González, a Colombian biologist and photographer who has worked on endangered species conservation and scientific pedagogy programs for over 10 years. Most recently, he has worked on documentary and book projects about environmental concerns, alongside his independent photographic art projects.

Peace and Violence in Colombia: A Contemporary Primer

In November 2016, the Colombian government and leftist guerrilla group the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), ratified peace accords after approximately 4 years of renewed negotiations. These accords signaled an end to a 54-year conflict, the longest-running one in the Western Hemisphere. The 2016 Havana Accords were touted as a sophisticated, inclusive agreement, and received praise from the international community for its design. It is an extensive agreement, including comprehensive rural reform, an increase in the plurality of political participation, replacement of illicit crop cultivation, reintegration of former combatants, a victim’s chapter for truth-finding and guarantees of non-repetition, and international observation of implementation. One of the main points of the victim’s chapter includes the creation of a tribunal court known as the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), which is responsible for collecting evidence and hearing cases regarding violence during the conflict. This court is not only hearing cases against the guerrillas, but also against members of the Colombian Armed Forces as well as the right-wing paramilitaries that were active throughout the course of the conflict.

Upon ratification of the accords, it appeared that they might be more successful than any other before in Colombia. The United Nations supervised a demobilization and disarmament process, which they declared completed in August 2017 with FARC handing in more than one weapon per combatant, more than was expected. Following disarmament, former combatants moved into over two dozen demobilization zones throughout the country in order to prepare for reintegration into society. As of 2018, the JEP began its work on investigating cases, another guerrilla group, the National Liberation Army (ELN) was at the negotiating table for a peace deal of their own, and the Kroc Institute at the University of Notre Dame, the party responsible for international monitoring of implementation, was reporting slow but steady progress on implementation of various points of the accords.

However, there was also significant opposition facing the implementation of the accords. Between 2016 and 2019, an estimated 734 activists and human rights leaders have been murdered, with an even higher number threatened and still under threat. The majority of these threats and murders have been against activists working in rural parts of the country on initiatives such as environmental protections, prevention of illegal mining, fighting against the presence of armed actors, and those activists working for the replacement of coca. These continued threats are destabilizing to the implementation to the accords and serve to deepen the divide between Colombia’s urban and rural populations. In addition to this systematic threat against activists, approximately 130 former FARC combatants have also been murdered or forcibly disappeared since demobilization began. When former combatants reached the demobilization and reintegration zones, they found an absence of healthcare, potable water, and shelter that had been promised by the government in the accords. In addition to these delays of immediate and basic needs, only a fraction of former combatants have been enrolled in the reintegration benefits promised in the accords. Due to these delays, three high-level FARC commanders left integrations zones in August 2018, and issued a call to FARC to return to arms earlier this year. It is estimated that approximately 15% of FARC has remobilized following or even previous to this call.

Right-wing candidate Iván Duque won the 2018 presidential elections and took office in August 2018. Upon his inauguration, he announced that he was not sure if he would continue negotiations with the ELN, Colombia’s biggest guerrilla group following the technical demobilization of FARC, and would only do so if additional conditions were met. In January 2019, a faction of the ELN set off a car bomb at a police academy in Northern Bogotá, killing 21 and injuring 80. This was the first time in decades that the central capital of Bogotá had been impacted directly by violence as a part of the conflict. This action guaranteed the total stop of negotiations between the group and the government for the foreseeable future.

Now-president Duque campaigned on a promise to ‘reform’ the divisive 2016 peace accords. To that end, during his time in office, he has cut the Truth Commission’s budget by 40%, sent the war crimes bill which allowed for the creation back to Congress, and eliminated a key reintegration agency for former combatants. These actions have created delays in once-promising implementation, and Duque’s additional labor, pension, privatization, and environmental reforms have created the perfect conditions for massive and historic protests in Colombia’s major cities. Entering the third weeks of protests, large-scale mobilization in Colombia’s capital of Bogotá continues, but that same mobilization has not transferred to more rural areas, which are also the parts of the country which continue to be the most impacted by a continuation of both direct and structural violence. In the following section, I discuss why.

The Urban/Rural Divide

Just as there exists a divide between the urban and rural reactions to Colombia’s ongoing protests, there has been a consistent divide in realities for the two populations. Largely due to high levels of violence in the countryside in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Colombia rapidly urbanized. Today’s population divide stands at approximately 70% urban, 30% rural. Colombia is a country of cities. However, the 30% rural population, largely made up of Afro-descendant and indigenous communities on their ancestral land, along with campesino farmers, have been by far the most impacted by the violence by a variety of armed actors throughout the course of Colombia’s conflict. A significant number of those impacted have been internally displaced to the larger cities of Bogotá, Cali, and Medellín. Still, many chose to stay, or could not leave, strategically significant and/or resource rich land in rural parts of the country. For decades, this land was fought over by paramilitary groups, a variety of left-wing guerrillas, the Colombian military, and allied drug trafficking and other criminal organizations for the environmental ability to grow coca, the first ingredient in what eventually becomes cocaine, natural resources such as gold, emerald, and oil mines, and access to the Pacific Ocean or other routes via rivers.

In many instances, a group which held territorial control over an area almost completely replaced the state. Guerrilla groups such as FARC would often fill such functions as regulating fishing rights and punishing thieves. After the 2016 peace accords, FARC left the areas that they had territorial control over, moving into their demobilization zones, leaving a vacuum of services, power, and control which the state refused to see. In that absence, different guerrilla groups, neo-paramilitary groups, or drug traffickers moved in to fight over the now freely available territory.

So, the question remains—why is state-laden capital Bogotá on its third straight week of protests, while the majority of the rural areas in the country continue with business-as-usual? My response, which hinges on interviews conducted with actors involved in social and economic justice initiatives in Colombia at the local, national, and international levels, is the following: why bother to protest a state that is not there to begin with, and has not been there, in living memory?

The State: Here, There, Nowhere?

This is not to discount the fact that there are people doing incredible work, based in Bogotá. People dedicated to the peace process, peacebuilding, and the concept of positive peace in general, whether they call it by that particular name or not. People who have, more or less, dedicated their life to these ideas. But for a long time, these people have been in the minority. Bogotá is often characterized by the rest of the country as a distant, uncaring, bureaucratic, traffic-laden disaster. With the paro nacional still in full force in the nation’s capital, many might also be thinking, “well, too little too late.”

But is it, really? Yes, perhaps Bogotá is finally mad enough about everything that other parts of the country have been resisting for decades to organize and mobilize on a large and diverse scale. But, as protestors continue to mobilize over a myriad of issues, all linking to this idea of positive peace, these protests can be used as real acts of allyship and solidarity, to put the voices of those most impacted by violence at the front and center of the protests, right in front of the symbols of central power in Colombia, in front of a state which refuses to see or hear them. Last week, the Resguardo Indigena (indigenous community defense guard) arrived from Cauca to join in the protests in central Bogotá. The department of Cauca has been one of the most impacted parts of Colombia throughout the conflict, and continues to be after the peace accords It is estimated that 88 indigenous activists have been murdered in Cauca since January 2016. Their arrival in Plaza de Bolívar was accompanied by thousands of students, union members, feminist groups, political parties, and other organizations.

When asked about their vision of a truly ‘post-conflict’ Colombia, almost every bureaucrat, technocrat, or elite I have asked has responded by discussing the need for true rural reform and provision of positive government services in all parts of the country. Despite this supposed consensus, it has been a slow-moving and difficult task. This difficulty lays in the durability of conditions which contribute to continued systems of structural violence, and the ways in which leaders and other members of the population turn a blind eye to those same conditions and systems. In optimistic terms, protests and other forms of mobilization in Colombia are strategies to make a state and other citizens ‘see’ the ways in which a lack of positive peace continues to impact citizens in huge ways, ways that continue all the way to central Bogotá.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Colombia at the Crossroads? The Road Ahead in an Election Year

- Colombia’s ‘Total Peace’ and Climate Change

- Indigenous Conflict Victims and the Growing Tent City in Bogotá

- Gender-Transformative Peacebuilding in Colombia

- Opinion – Colombia’s Transitional Justice System Sets Precedent for Accountability

- Colombia: Coronavirus in a Scenario of Humanitarian Crisis