Although the field of International Relations (IR) has seen a cascade of newly developed theories over the last decades, realism has remained one of the most prevalent theories in the field. In spite of this prevalence, realism has kept evolving over these last decades, with new varieties being developed and old varieties being expanded on. While there is not yet a theoretical framework within the discipline of IR which analyses the influence of domestic discourse on shaping foreign policy, some scholars of IR have explored the intersection of domestic politics and international relations.[1] Nonetheless, existing theories of realism that do acknowledge domestic politics as a factor in international relations do not analyse whether domestic politics are a determining factor in shaping foreign policy. Moreover, these theories fail to provide a framework through which to analyse how domestic considerations shape international relations.

In this paper I will argue that international relations are often shaped by domestic considerations and explore how this synergy between domestic and foreign policy can be analysed within a realist theoretical framework. I will do so by giving a short overview of realism, particularly in terms of the global political economy, and intermestic affairs; policies that blur the line between the domestic and the international sphere. Afterwards, I will propose a thesis of intermestic realism. Finally, I will offer a short instrumental case study on intermestic considerations in the US-China trade war. By doing so, this paper aims to show how a frame of intermestic realism can be used to explain how domestic considerations can shape international relations.

Realism and the Global Political Economy

“The history of the nations active in international politics shows them continuously preparing for, actively involved in, or recovering from organized violence in the form of war.”[2] This quote by political scientist Hans J. Morgenthau, the father of realist thought in IR, illustrates the core idea of realism: the perpetual struggle for power in international politics, which inevitably results in war. His classical realist view explains the continual power struggle in international relations as a consequence of human nature and, therefore, as a core aspect of humanity.[3]

Since Morgenthau’s classical realism, there have been numerous variations and additions to this theory.[4] Kenneth Waltz’s neorealism stresses the anarchical nature of the international system, while nonetheless approaching it as “a system with a precisely defined structure.”[5] This approach is the crux of neorealism, for it allows for more distinct theorising than classical realism can. Another significant addition to realism was the theory of defensive realism, which argues that when an offensive stance within the international system becomes too difficult, expansion will decline. If the costs for an offensive strategy become too high, the reduced power struggle will lead to cooperation between states and relative peace, mitigating the anarchical nature of the international system.[6]

These examples of realist thought approach international relations as conflict in the form of violent warfare. Nonetheless, realism can be applied to a non-violent war as well. Journalist and historian E.H. Carr argues that “the aim of mercantilism … was not to promote the welfare of the community and its members, but to augment the power of the state.”[7] As such, he approaches economic power as a tool for states to advance within the realist power struggle. Robert Gilpin, a realist scholar of IR, has similar views on the global political economy, arguing that “the relatively large size of the hegemon’s market is a source of considerable power and enables it to create an economic sphere of influence.”[8]

Gilpin differs from contemporaries like Waltz in his approach to assessing the possibility of conflict. IR scholar William C. Wohlforth explains that the difference between these two authors is that Waltz assumes that “states are conditioned by the mere possibility of conflict,” while Gilpin assumes that “states make decisions based on the probability of conflict.”[9] As such, while both authors are realists, they differ in the extent to which they assume conflict is inevitable. While Gilpin may not have found as much influence as Waltz has, he is an influential realist scholar of IR concerning the global political economy. Gilpin argues that by opening their economic sphere up to states, or by closing it to others, a hegemon uses its economic power to contribute to managing the global market economy, which further “enables the hegemon to exploit its dominant position.”[10] As such, a trade war can be seen as a realist power struggle between two states in which sanctions and tariffs are the tools used to disadvantage the other state.

However, an international economic power struggle not only affects a country’s international relations but also has a significant effect on its domestic sphere. As such, there is a synergy between international relations and the domestic sphere, particularly concerning economic affairs. In the following section, I will outline the concept of “intermestic affairs” and examine how this relationship between foreign and domestic policy can be analysed in realist thought.

Intermestic Realism

The term “intermestic” originates from a 1979 Foreign Affairs article by Bayless Manning, best known for being the first president of the Council of Foreign Relations. In his article, Manning argues that some foreign policies have such a significant direct effect on the domestic sphere, that the deliberations behind them are rooted in both international and domestic considerations.[11] Manning’s original conception of these intermestic affairs mainly involved policies that directly affected the domestic economy, such as energy policies, tariffs, and embargoes.[12] For example, an embargo on another country’s oil sales may directly affect domestic oil prices. As such, the decision of whether or not to place an embargo in the first place is guided by not only international considerations but also domestic ones.

While Manning’s original conception of intermestic affairs was mostly concerned with the dividing line between the international political economy and the domestic economy, others have broadened the scope of intermestic affairs to include the effect that foreign policy has on domestic public opinion and the effect of public opinion on foreign policy.[13] Historian Fredrik Logevall has further developed the concept of intermestic affairs. Logevall’s main argument in his book Choosing War is that one of the main reasons for President Lyndon B. Johnson’s decision to remain in Vietnam – while Johnson himself was hesitant to continue the war effort – had to do with his diminished chances for re-election had he been the president who lost the Vietnam war.[14] As such, Logevall broadens the definition of intermestic policy to mean an international policy that affects or has implications on the domestic discourse.

The concept of intermestic affairs has become increasingly influential in the field of diplomatic history over the last decade.[15] However, scholars of IR have also started to focus more on the role of domestic politics in international relations.[16] Since the start of the 21st century, the use of qualitative methodology has “become more deeply institutionalised” in the field of IR.[17] This qualitative turn allows for a more in-depth analysis of the less measurable causes and effects of diplomatic history and International Relations, like those policies of an intermestic nature which are harder to quantify.

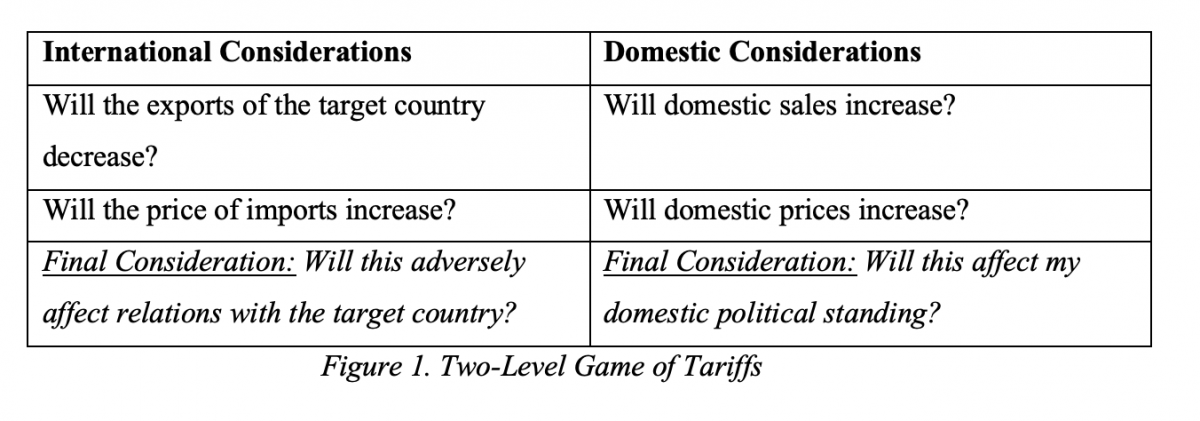

Considerations grounded in intermestic affairs can be examined within a realist framework by approaching these considerations as a power struggle that plays out simultaneously on a domestic and international level. Political scientist Robert D. Putnam approaches such a struggle as a two-level game wherein a government is pressured domestically by interest groups for domestically favourable policies while trying to minimise the possible negative international consequences of pursuing such a policy.[18]

The two-level game visualised in figure 1 uses the example of placing tariffs on another country’s products. Tariffs are a classic example of how foreign policy affects the domestic sphere. Realism is essentially a theory of the struggle for power. Therefore, intermestic realism examines the power struggle that originates from a particular action both internationally and domestically.

The last row from figure 1 is the consideration regarding the outcome of the first two rows. The answer to this final row explains whether to pursue the policy or not, based on the power gained both internationally and domestically. Domestic power can be gained if this intermestic policy increases one’s domestic political standing, and international power can be lost if this policy adversely affects the relations with the target country. Therefore, from a perspective of intermestic realism, a government will choose to pursue a policy if the domestic power gained is greater than the international power lost and vice-versa.

Intermestic Realism and the US-China Trade War

China and the US have been in a trade war since the 22nd January 2018. Both countries have taken increasingly heavy blows to their economy since the trade war began. As such, this trade war does not seem to be just economically motivated, but also rooted in political considerations. Although the trade war was instigated by the US, the country has seemingly gained neither an economic advantage nor a political one.[19] To the contrary, besides the economic harm that this trade war has inflicted on the US, if anything their global soft power and goodwill in China have deteriorated, rather than expanding their global influence. However, this does not mean that China comes out of this trade conflict as the victor. A recent scenario analysis has shown that China may suffer a 1.1% increase in unemployment and a 1% GDP loss.[20]

Since the US-China trade war does not seem rooted in solely economic considerations, one could argue that this conflict is a political power struggle between two dominant world powers. Taking a realist approach could help us understand what the motivation behind this conflict is. However, since the geopolitical gain of either party is not immediately apparent, there may be domestic factors shaping international relations in this conflict.

In the case of China, the intermestic nature of the trade war becomes apparent by placing their economic policies in the context of the global political economy. One of the US’s main grievances with China leading up to the trade war regards intellectual property (IP) rights.[21] The World Trade Organization (WTO), which China joined in 2001, stresses the need to “ensure that IP rights are respected in an effective, timely and accessible manner, alongside the legitimate interests of others concerned.”[22] As such, with the important role that the WTO plays in the global political economy as an institution, abiding by IP rights is important to operate within the international system. Neglecting the enforcement of these rights harms a state’s international standing, as it violates international rules. As such, whether or not to enforce IP rights is an international consideration for China. Referring to figure 1, China’s final international consideration is whether not enforcing IP rights will adversely affect relations with the US and the broader international community.

However, China’s international consideration is contrasted with a domestic consideration: how will enforcing IP rights affect the domestic sphere? Economists Falvey, Foster, and Greenaway explain how the protection of IP rights affects countries differently depending on their level of development. Through a threshold regression analysis, they show that for high-income countries the protection of IP rights encourages innovation and for low-income countries it encourages technology flows.[23] However, they found that the protection of IP rights in middle-income countries slows down knowledge diffusion and discourages imitating production which negatively impacts economic growth.[24] As other authors have pointed out, this negative relation for middle-income countries between economic growth and the protection of IP rights holds true in the case of China.[25]

As such, the question of whether or not to abide by international IP rights standards is rooted in both domestic and international considerations for China. Abiding by these standards would improve US-China relations and improve China’s international standing and legitimacy internationally. However, these outcomes are contrasted to the possible harm that abiding by these standards may have on China’s domestic economy and economic growth. As such, China’s considerations in the trade war are intermestic, for they are based on the power gained or lost both domestically and internationally.

In the case of the US, scholars have pointed out that allegedly unfair US-China trade relations were an important campaign point for now President Donald Trump in the 2016 election.[26] Political scientist Lowell Dittmer points out that elections often play a vital role in shifting foreign policy.[27] Dittmer puts forth the examples of the 1952 election and the end of the Korean War and the 1968 election and the withdrawal from Vietnam as examples of how intermestic considerations regarding an upcoming election can influence foreign policy decisions.[28] Handley and Limão argue that US-China trade relations as a talking point in the Trump campaign served two purposes: (1) it fed into the populist-nationalist sentiment that the economic hardships of the working and middle class were due to international trade and immigration; (2) the threats made toward China during his campaign had a “unifying principle,” uniting people against a “rigged” international system.[29]

The strategy borne out of this sentiment is further elaborated on in a policy paper by Navarro and Ross, both senior policy advisors to the Trump campaign at the time of their paper’s publication. They argue that, due to China entering the WTO, “Mr. and Ms. America are left back home without high-paying jobs,” further calling China’s entrance into the WTO “a critical catalyst for America’s slow growth plunge.”[30] The Trump campaign’s adverse attitude towards China is most clearly seen through its “America First” rhetoric, argued by some to be a justification for the ensuing protectionist policies.[31] It is this particular discourse that served as a major focal point during Trump’s campaign. The use of this rhetoric in relation to the US-China trade war, shows how – at least partially – the trade war is rooted in intermestic considerations.

Applying the effects of the US-China trade war to the two-level game of tariffs as shown in figure 1, allows us to examine how the instigation of the trade war is rooted in intermestic considerations. The adverse effects of the trade war on international economic outcomes, geopolitical standing, and US-China relations, are international considerations for not engaging in the trade war. However, the domestic benefits gained through the America First rhetoric make up for the adverse international effect by increasing the domestic power of the Trump campaign. As such, the perceived domestic power gained by engaging in the trade war outweighs the perceived international power lost.

Conclusion

This paper has sought to explain how domestic considerations can shape international relations through a lens of intermestic realism. Applying the concept of intermestic affairs to realist theory, allows us to examine the consideration of policies that affect a government both nationally and internationally. Through a lens of intermestic realism, a government will choose to pursue a policy if the domestic power gained is greater than the international power lost or vice-versa.

The case of the US-China trade war shows the importance of domestic considerations in determining foreign policy and shaping international relations. While the international considerations for the US-China trade war have negative consequences for both countries, engaging in this trade war has clear domestic benefits. As such, while these countries do not gain international power from their international relations, the domestic power gained by their actors offset these adverse effects.

The goal of this paper is to introduce a thesis of intermestic realism, which analyses the power of domestic interests in international relations. While this paper is by no means a complete overview of the intersection between the domestic and international sphere, or a thorough analysis of intermestic considerations in the US-China trade war, it hopes to serve as a guideline for the development of a theory of intermestic realism.

Bibliography

Amiti, Mary, Stephen J. Redding, and David Weinstein. The Impact of the 2018 Trade War on US Prices and Welfare. No. w25672. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2019.

Barilleaux, Ryan J. “The President, ‘Intermestic’ Issues, and the Risks of Policy Leadership.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 15, no. 4 (1985): 754-767.

Brenner, Philip, Patrick J. Haney, and Walter Vanderbush. “The Confluence of Domestic and International Interests: US policy toward Cuba, 1998–2001.” International Studies Perspectives 3, no. 2 (2002): 192-208.

Brooks, Stephen G. “Dueling Realisms.” International Organization 51, no. 3 (1997): 445-477.

Carr, Edward Hallett. Nationalism and After. London: Macmillan, 1945.

Chong, Terence Tai Leung, and Xiaoyang Li. “Understanding the China–US Trade War: Causes, Economic Impact, and the Worst-Case Scenario.” Economic and Political Studies 7, no. 2 (2019): 185-202.

Dittmer, Lowell. “American Asia Policy and the US Election.” Orbis 52, no. 4 (2008): 670-688.

Elman, Colin, and Miriam F. Elman. “The Role of History in International Relations.” Millenium 37, no. 2 (2008): 357-364.

Falvey, Rod, Neil Foster, and David Greenaway. “Intellectual Property Rights and Economic Growth.” Review of Development Economics 10, no.4 (2006): 700-719.

Foyle, Douglas C. “Public Opinion and Foreign Policy: Elite Beliefs as a Mediating Variable.” International Studies Quarterly 41, no. 1 (1997): 141-169.

Gienow-Hecht, Jessica. “What Bandwagon? Diplomatic History Today.” Journal of American History 95, no. 4 (2009): 1083-1086.

Gilpin, Robert. The Political Economy of International Relations. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987.

Handley, Kyle and Nuno Limão. “Trade under T.R.U.M.P. Policies” in Economics and Policy in the Age of Trump. Edited by Chad P. Brown, 141-152. London: CEPR Press, 2017.

Hocking, Brian, and Michael Smith. Beyond Foreign Economic Policy. London: A&C Black, 1997.

Jaskuła, Paweł. “The Redefinition of Foreign Policy of the United States since Trump’s Election: The Case of Trade War with China.” International Studies, 23, no. 1 (2019): 161-182.

Jervis, Robert. “Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma.” World Politics 30, no. 2 (1978): 167-214.

Katzenstein, Peter J. “International Relations and Domestic Structures: Foreign Economic Policies of Advanced Industrial States.” International Organization 30, no. 1 (1976): 1-45.

Keohane, Robert O., and Joseph S. Nye, Power and Interdependence. Boston: Little, Brown, 1977.

La Croix, Sumner, and Denise Eby Konan. “Intellectual Property Rights in China: The Changing Political Economy of Chinese–American Interests.” World Economy 25, no.6 (2002): 759-788.

Logevall, Fredrik. Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam. Oakland: University of California Press, 2001.

Logevall, Fredrik. “Domestic Politics” in Explaining the History of American Foreign Relations, Edited by Frank Costigliola and Michael J. Hogan, 151-167. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Logevall, Fredrik. “Politics and Foreign Relations.” Journal of American History 95, no. 4 (2009): 1074-1078.

Manning, Bayless. “The Congress, The Executive, and Intermestic Affairs.” Foreign Affairs 57, no. 2 (1979): 306-324.

Milner, Helen V., and Dustin H. Tingley. Sailing the Water’s Edge: The Domestic Politics of American Foreign Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Morgenthau, Hans J. Politics Among Nations. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1948.

Navarro, Peter and Wilbur Ross. “Scoring the Trump Economic Plan: Trade, Regulatory, & Energy Policy Impacts,” 2016. https://assets.donaldjtrump.com/Trump_ Economic_Plan.pdf.

Peng, Mike, David Ahlstrom, Shawn Carraher, and Weilei Shi. “History and the Debate over Intellectual Property.” Management and Organization Review 13, no. 1 (2017): 15-38

Putnam, Robert D. “Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: The Logic of Two-Level Games.” International Organization 42, no. 3 (1988): 427-460.

Snyder, Jack. “One World, Rival Theories.” Foreign Policy 145 (2004): 52-62.

Snyder, Jack. Myths of Empire: Domestic Politics and International Ambition. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013.

Tarzi, Shah M. “The Trump Divide and Partisan Attitudes Regarding US Foreign Policy: Select Theoretical and Empirical Observations.” International Studies 56, no. 1 (2019): 46-57.

Walt, Stephen M. “International Relations: One World, Many Theories.” Foreign Policy 110 (1998): 29-46.

Waltz. Kenneth N. “Realist Thought and Neorealist Theory.” Journal of International Affairs 44, no.1 (1990): 21-37.

Wohlforth, William C. “Gilpinian Realism and International Relations.” International Relations 25, no. 4 (2011): 499-511.

World Trade Organization. “Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights.” World Trade Organization, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/ipenforcement_e.htm. Accessed 11 December 2019.

Yarhi-Milo, Keren. “After Credibility: American Foreign Policy in the Trump Era.” Foreign Affairs 97, no. 1 (2018): 68-77.

Yin, Jason Z., and Michael H. Hamilton. “The Conundrum of US-China Trade Relations Through Game Theory Modelling.” Journal of Applied Business and Economics 20, no. 8 (2018): 133-150.

Zeiler, Thomas W. “The Diplomatic History Bandwagon: A State of the Field.” Journal of American History 95, no. 4 (2009): 1053-1073.

Notes

[1] The most notable attempt in creating such a framework is: Robert D. Putnam. “Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: The Logic of Two-Level Games.” International Organization 42, no. 3 (1988): 427-460. For other important contributions to the hybrid space of the domestic sphere and international relations, see for example: Peter J. Katzenstein. “International Relations and Domestic Structures: Foreign Economic Policies of Advanced Industrial States.” International Organization 30, no. 1 (1976): 1-45; Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye, Power and Interdependence. (Boston: Little, Brown, 1977); Brian Hocking, and Michael Smith. Beyond Foreign Economic Policy. (London: A&C Black, 1997); Jack Snyder. Myths of Empire: Domestic Politics and International Ambition. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013).

[2] Hans J. Morgenthau. Politics Among Nations. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1948), 21.

[3] Morgenthau. Politics Among Nations, 13.

[4] Stephen G. Brooks. “Dueling Realisms.” International Organization 51, no. 3 (1997): 445-477; Stephen M. Walt. “International Relations: One World, Many Theories.” Foreign Policy 110 (1998): 29-46; Jack Snyder. “One World, Rival Theories.” Foreign Policy 145 (2004): 52-62.

[5] Kenneth N. Waltz. “Realist Thought and Neorealist Theory.” Journal of International Affairs 44, no.1 (1990): 29-32.

[6] Robert Jervis. “Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma.” World Politics 30, no. 2 (1978): 176.

[7] Edward Hallett Carr. Nationalism and After. (London: Macmillan, 1945), 5-6.

[8] Robert Gilpin. The Political Economy of International Relations. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), 76.

[9] William C. Wohlforth. “Gilpinian Realism and International Relations.” International Relations 25, no. 4 (2011): 503.

[10] Gilpin. The Political Economy, 76.

[11] Bayless Manning. “The Congress, The Executive, and Intermestic Affairs.” Foreign Affairs 57, no. 2 (1979): 306-324.

[12] Manning. “Congress, Executive, and Intermestic Affairs,” 308-309.

[13] Ryan J. Barilleaux. “The President, ‘Intermestic’ Issues, and the Risks of Policy Leadership.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 15, no. 4 (1985): 754-767; Fredrik Logevall. “Domestic Politics” in Explaining the History of American Foreign Relations, Edited by Frank Costigliola and Michael J. Hogan, 151-167. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016); Shah M. Tarzi. “The Trump Divide and Partisan Attitudes Regarding US Foreign Policy: Select Theoretical and Empirical Observations.” International Studies 56, no. 1 (2019): 46-57.

[14] Fredrik Logevall. Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam. (Oakland: University of California Press, 2001).

[15]See: Fredrik Logevall. “Politics and Foreign Relations.” Journal of American History 95, no. 4 (2009): 1074-1078; Jessica Gienow-Hecht. “What Bandwagon? Diplomatic History Today.” Journal of American History 95, no. 4 (2009): 1083-1086; Thomas W. Zeiler. “The Diplomatic History Bandwagon: A State of the Field.” Journal of American History 95, no. 4 (2009): 1053-1073.

[16] Colin Elman, and Miriam F. Elman. “The Role of History in International Relations.” Millenium 37, no. 2 (2008): 361; Philip Brenner, Patrick J. Haney, and Walter Vanderbush. “The Confluence of Domestic and International Interests: US policy toward Cuba, 1998–2001.” International Studies Perspectives 3, no. 2 (2002): 192-208; Douglas C. Foyle. “Public Opinion and Foreign Policy: Elite Beliefs as a Mediating Variable.” International Studies Quarterly 41, no. 1 (1997): 141-169; Helen V. Milner, and Dustin H. Tingley. Sailing the Water’s Edge: The Domestic Politics of American Foreign Policy. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).

[17] Elman and Elman. “The Role of History,” 363.

[18] Putnam, “Diplomacy and Domestic Politics,” 434.

[19] Mary Amiti, Stephen J. Redding, and David Weinstein. The Impact of the 2018 Trade War on US Prices and Welfare. No. w25672. (Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2019).

[20] Terence Tai Leung Chong, and Xiaoyang Li. “Understanding the China–US Trade War: Causes, Economic Impact, and the Worst-Case Scenario.” Economic and Political Studies 7, no. 2 (2019): 199-201.

[21] For an overview of this dispute, see: Mike Peng, David Ahlstrom, Shawn Carraher, and Weilei Shi. “History and the Debate over Intellectual Property.” Management and Organization Review 13, no. 1 (2017): 15-38.

[22] World Trade Organization. “Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights.” World Trade Organization, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/ipenforcement_e.htm. Accessed 11 December 2019.

[23] Rod, Neil Foster, and David Greenaway. “Intellectual Property Rights and Economic Growth.” Review of Development Economics 10, no.4 (2006): 712.

[24] Falvey, Foster, and Greenaway. “Intellectual Property Rights,” 712.

[25] Falvey, Foster, and Greenaway. “Intellectual Property Rights,” 700-719; Sumner La Croix, and Denise Eby Konan. “Intellectual Property Rights in China: The Changing Political Economy of Chinese–American Interests.” World Economy 25, no.6 (2002): 759-788.

[26] Paweł Jaskuła, “The Redefinition of Foreign Policy of the United States since Trump’s Election: The Case of Trade War with China.” International Studies, 23, no. 1 (2019): 162-165; Keren Yarhi-Milo. “After Credibility: American Foreign Policy in the Trump Era.” Foreign Affairs 97, no. 1 (2018): 72-75.

[27] Lowell Dittmer. “American Asia Policy and the US Election.” Orbis 52, no. 4 (2008): 670.

[28] Dittmer. “American Asia Policy,” 670.

[29] Kyle Handley and Nuno Limão. “Trade under T.R.U.M.P. Policies” in Economics and Policy in the Age of Trump. Edited by Chad P. Brown, 141-152. (London: CEPR Press, 2017), 142.

[30] Peter Navarro and Wilbur Ross. “Scoring the Trump Economic Plan: Trade, Regulatory, & Energy Policy Impacts,” 2016. https://assets.donaldjtrump.com/Trump_ Economic_Plan.pdf, 3-4.

[31] Jason Z. Yin, and Michael H. Hamilton. “The Conundrum of US-China Trade Relations Through Game Theory Modelling.” Journal of Applied Business and Economics 20, no. 8 (2018): 135.

Written by: Tom Meinderts

Written at: Leiden University

Written for: Dr. André Gerrits

Date written: December / 2019

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Limits of the Scientific Method in International Relations

- Tracing Hobbes in Realist International Relations Theory

- Rehabilitating Realism Through Mohammed Ayoob’s “Subaltern Realism” Theory

- International Relations Is Not Post Postcolonialism in the Twenty-First Century

- Cultural Relativism in R.J. Vincent’s “Human Rights and International Relations”

- A Critical Reflection on Sovereignty in International Relations Today