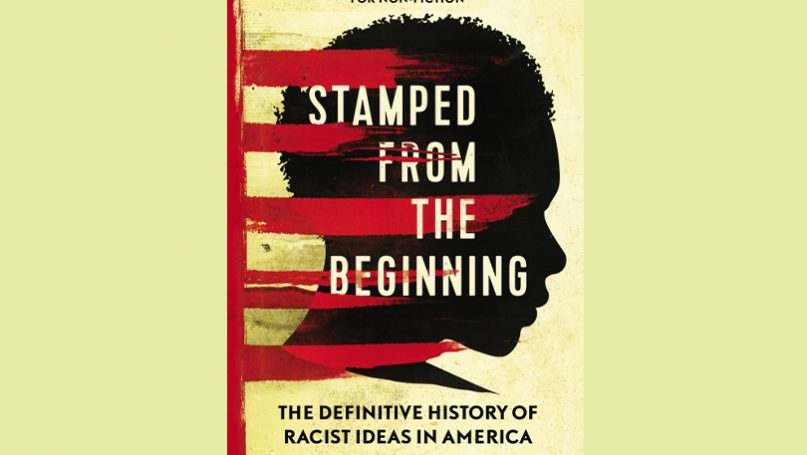

Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America

By Ibram X. Kendi

Penguin, 2017

Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning provides one of the most thought-provoking accounts of American racial history. Kendi’s work is not confined to the boundaries of American political space. As much as Kendi examines the history of racism in the political discourse in America and its resultant effect on the lives of millions of people of color, he also implicitly “internationalizes” racial discourse. And in doing so, makes his work a theorization of global anti-blackness. Kendi’s utilization of the Haitian revolution of 1804, Obama’s Kenyan roots, and Ghanaian independence followed by the country’s pivot to the Soviets right after independence are episodes of black success/decisions that greatly impacted how Blackness was “othered.”

Kendi, a professor of history and international relations at American University in Washington, D.C., where he researches race and discriminatory policy in American politics, questions international politics as often influenced by either overt or subtle racism. This is not a new area. Robert Vitalis also explored the central role of racism in the formation of Western empires, the triumph of capitalism, and the industrialization of western states. Vitalis’ work positioned racism at the center in modernity in White World Order, Black Power Politics. Similarly, Duncan Bell’s work Reordering the World focused on the contradiction between liberal political thought and the absurdity of imperialism in 19th century British societies. Robert Bates, V.Y. Mudimbe and Jean O’barr wrote in Africa and the Disciplines that “research into the experiences of persons of African descent in the modern world poses fundamental challenges to Western society’s understanding of itself” (Bates, Mudimbe, & O’Barr, 1993; xi). In The Predicament of Blackness, Jemima Pierre argues that a meaningful conversation on race must reckon that the “postcolonial societies are structured through and by global white supremacy” (Pierre, 2013;1).

Kendi’s work adds to these debates using the dual and dueling narratives of American racial progress and the concurrent resurgence and evolution of racism. Kendi writes that “racist progress has constantly followed racial progress” (p.xi). Stamped from the Beginning begins at the escalation of deaths of young Black men at the hands of armed police officers in the middle of Obama’s second term. The election of Donald Trump, a right-wing candidate who emboldened his political career by challenging the validity of Barack Obama’s birth certificate, further entrenches the summersaulting of racial progress with racist ideas.

While Stamped from the Beginning, is a story of the mutation of racist ideas, it is also one of the failures of American attempts at uprooting racism. Kendi is critical of the ideas of self-sacrifice, education, and economic advancement of a section of Black people as a panacea of racism, and the notion that white people could be persuaded away from racist views if they only saw black people working to lift themselves from their lowly station, dubbing this process uplift suasion. Using the historic election of Barack Obama, followed by his historical opposition, he surmises that the “more black people uplift themselves, the more they will find themselves on the receiving end of racist backlash” (p.505). The problem with uplift suasion is that “while negative portrayals of black Americans reinforce racist views, positive ones do not weaken them – they are simply dismissed as exceptions” (p.124).

Kendi asserts that American racial history should be examined from the lenses of three groups. First are the segregationists, who are outright anti-blackness. Segregationists focus on the concept of “black pathology,” blacks as “stamped from the beginning.” Assimilationists form the second group of actors, who argue that black people can integrate with mainstream American culture by shedding the pathological aspects of blackness caused by culture, environments, poverty, and the psychological effects of discrimination. For this group, Blackness can be shaded or shaped to conform to whiteness in looks and behavior. The last group, which forms the analytical framework upon which Kendi bases his work, are the anti-racists. Anti-racists argue that Blackness has always been problematic in American history. Therefore, a racist idea is “any concept that regards one racial group as inferior or superior to another racial group in any way” (p.5). In the same token, anti-black racist ideas are those that “suggest that Black people, or any group of Black people, are inferior in any way to another racial group” (p.5).

Kendi uses five influential characters in American history from the colonial era to the present age as tour guides to explore the landscapes of the evolution of racial ideas. He starts with Cotton Mather, the New England Puritan Minister, who wrote that “dark souls of enslaved Africans would become white when they become Christians” (p.6). While Thomas Jefferson proclaimed that “all Men are created equal,” it is difficult to argue that he extended his definition to “all men” – including Black men and women. While Jefferson defended the equality of the White men in America, he was not able to shield the equality of over 200 colored slaves he owned in Virginia (p.104). Kendi examines the life of William Garrison, the abolitionist, journalist, and suffragist who founded the well-known newspaper The Liberator. However, Kendi argues that Garrison was an assimilationist and not anti-racist. Garrison felt that slavery had “imbruted” black people (p.187) and that perhaps Black people could be “developed by Northerners” (p.237). On W.E.B. Dubois, the first Black intellectual, Kendi argues that Dubois started as an assimilationist but ended-up an anti-racist. Dubois’ double-consciousness faded as he realized that any attempts at assimilation always faltered at the altar of American racialized politics. The unquestionable anti-racist in his count is Angela Davis, the radical civil rights leader in the 1960s.

Kendi’s work brings to force the idea that racial policies in America are sprung from a collection of interests ranging from economic, political, and social concerns. Furthermore, these ideas function to speed-up resistance to racial progress, which ends up entrenching racial disparities. Underlined in Kendi’s work is the argument that “there is nothing wrong with Black people as a group” (p.11). We must accept that Black American’s history of oppression has “made black opportunities – not black people – inferior (p.11). In order to “truly be antiracists, we must also oppose all of the sexism, homophobia, colorism, ethnocentrism, nativism, cultural prejudice, and class bias teaming and teaming with racism to harm so many black lives” (p.502).

The ramafication is that regardless of political and legislative rights, the racism manifested in the form of enslaving black people and the colonization of Africa are conceivably the most destructive forces on the self-esteem of people of color. It was a successful project that achieved the desired goal of erasing an African worldview and its significance. Today, the remaking of humanity from the lenses of the previously colonized people is only at a primary stage. Moreover, this process, although legitimate, is forever contested by forces of Westernization and political exclusion, what Ibram Kendi has described as “anti-blackness.”

Kendi is not favorable to good intentions or good deeds, as seen in the cases of Abraham Lincoln or FDR (labeled friend of black folks), he terms these as assimilation. Instead, he is interested in rooting out anti-blackness and racism. In doing so, his ideas sacrifice moral correctness at the altar of the complicated and convoluted politics of race. The pursuit of personal purity on race exposes his work as one that runs contrary to the evolution of race. In short, can we examine puritan ethos the same way as we do to those of the current generation? It is not deniable that perspectives on race have changed from the era of Cotton Mathers in the 17th century, evolved during Angela Davis’s 1960s, and reformed in Obama’s presidency. It is not a question of whether America has a problem with race, this is undeniable; it is one of whether an individual or the system at large can be genuinely and thoroughly anti-racist.

Kendi clearly articulates that racial progress is not linear and progressive. Racial progress in America, at least, is a cyclical and convoluted process that is often shaped with discourse prevalent at the time. Thus, Kendi invites us to understand why Thomas Jefferson is worrisome of freed-slaves, shocked at the speed of the Haitian revolution, and is obstinate about the inalienable rights of all men. In contrast, Jefferson himself engages in an illicit affair with Sally Hemmings, a woman who self-identified as black.

Therefore, in places such as continental Africa, whiteness becomes a symbol of knowledge and power. Understandably, the pursuit of whiteness often drives people to make choices such as skin lightening. On an external surface, one easily judges individuals who partake in such activities as victims of self-hate, though, an intellectual analysis shows their attempt at whitening as a quest for power. The lessening of blackness gathers privileges that are reserved for the colonialists – it is a flawed attempt at assimilation. In short, Kendi’s pursuit of anti-blackness is the quest for global humanism.