This is an excerpt from Fieldwork as Failure: Living and Knowing in the Field of International Relations. Get your free copy from E-International Relations.

I got off the bus and after a few moments, I figured out the right direction. It took me about ten minutes to find the address which was stated on yad2, an Israeli version of craigslist, where the owners of a family house were advertising a small studio for rent. I buzzed at the door and was quickly let into the house. I met a young couple who offered me coffee and then showed me the sizeable room upstairs, with a shower, toilet, and a separate entrance from the street. It seemed perfect. Not only the particular room which would suit me quite well, but also the Israelis who were renting it and seemed fairly nice and communicative, qualities which would be perfect for my fieldwork. Even more importantly, the location fitted the criteria of my research in Israel/Palestine exactly: we were in a small settlement in the West Bank, a sort of community that I set to research for my doctoral project on depoliticisation of contested environments. However, I did not take the room, nor did I take any of the other three that I went to see over the next few days.

The reason was fairly simple: after seeing each of them, I quickly realised that my mental state would run a significant risk of deterioration. By that point, I had been experiencing depressive episodes for more the ten years. I could immediately foresee that the environment in the settlement, and the loneliness the stay would entail, would likely lead to psychological complications on my part. This decision would, according to many standards, constitute a missed research opportunity, or even a failure – by almost any conceivable academic criteria, I should have moved to the settlement. My apartment hunting and the surrender was thus one of the first instances in which my mental state shaped my fieldwork in Israel/Palestine. In what follows I show that attending to my mental condition is necessary to really grasp the contours of my research, how it proceeded, and how I approached it.

Essentially, then, this piece is an attempt to come to terms with what a lot of people would call ‘mental illness’, namely depression, and how it intersects with my academic work. In writing and publishing this chapter, I hope to show that the personal and the academic are intimately intertwined: my encounters with depression proved deeply formative for my intellectual and later academic self, with tangible repercussions for my fieldwork as well. Through disclosing some of my experiences, I want to show that our research, prisms we adopt, and approaches we take are inseparable from matters often condoned in the academic discourse as personal and irrelevant. Contrary to this trend, I illustrate that my mental condition is one of the most important ‘facts’ impacting my work.

I want to start with a disclaimer of sorts because I am well aware that my issues were never serious to the extent to which they had been for many others. Still, it proved repeatedly disruptive for my life and the lives of people around me, and as such I feel it further justifies my efforts here. However, for me it is also an exercise in coping with these issues. Although they represent only a particular facet of the whole condition, I have gradually realised that thinking about the impact my condition has on my work enables me to objectify my mental states, detach myself from these experiences and make sense of them. Perhaps writing this piece is an attempt at solidifying this analytical distance.[1]

What follows is composed of various segments that I have written over the course of the last four years or so in various states of mind and being, as well as sensations, experiences, and memories that I have not kept in a written form. I’ve come to think about all this as a peculiar type of archive, an archive that can be organised and from which different files can be extracted so that they can contribute to the narrative I want to offer here. I suppose all life experiences can be understood as such an archive, and indeed this is how social scientists often treat others’ lives. But for some reason, I had never really thought about mine in this way until my fieldwork. What I realised as I was writing these various segments is that my reflection on my mental health led me to reorganise the way I approach my self.[2]

Illness and Me

Spring 2016, Ariel

I first got depression when I was 17 years old. The event (or rather a series of events) that triggered this state of my mental health, this state of me, was quite banal as I can clearly see now (or rather as my current self understands it). In fact, it seems so silly that despite my decision to write this piece, I still cannot push myself to talk about it. In any case, at the time, it meant a great deal to me. And as I realise now, it was a transformative experience in many regards.

My condition was not too serious. I was exhibiting some classical symptoms like inability to sleep properly, anxiety, and absence of appetite, but I could still more or less function on an everyday basis. For several months, I was seeing a psychiatrist which I felt was helpful. He provided some food for thought which I seemed to digest quite well, and depression left me in the course of half a year or so. What stayed with me was the memory, a trail, an imprint of the intensely bodily, yet somehow also vaguely mental feeling. I realised later that those would be somatic expressions of my condition, of ‘a mood disorder marked especially by sadness, inactivity, difficulty with thinking and concentration, a significant increase or decrease in appetite and time spent sleeping, feelings of dejection and hopelessness, and sometimes suicidal thoughts or an attempt to commit suicide’ as defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary.[3]

These sensations returned repeatedly. Gradually, I discovered that ‘normal’ pain, i.e. physical pain, could help to alleviate the mental dislocations and anguish. I started to cut myself from time to time, although, in general, the intervals were a year-or-so long. Cuts on hands proved (unsurprisingly) too visible and tended to raise questions from people around me. I thus resorted to cutting my legs – the cuts could then be covered by trousers (I usually cut myself on calves), or I could come up with a reasonably plausible story about them being the result of me running through bushes (I like jogging) rather than a product of a chemical disbalance in my brain.

This practice of mine has never been uncontrollable, nothing like the images of bodies covered in self-imposed scars. Mine were very modest scars, almost innocent. Nevertheless, in summer 2014, my condition escalated, and I started to take anti-depressants – I am still using them at the time of writing – as well as attending psychotherapy (although with some breaks). The treatment usually proved to be quite effective, but not always.

Actually, I felt the first signs of this condition as I was walking around Ariel, an Israeli settlement in the northern part of the West Bank, where I was conducting my Ph.D. fieldwork.[4] I felt the things that usually precede and accompany depression, mostly loneliness and self-disgust. As I was passing by fire places (it was Lag BaOmer)[5], I started to think about writing down these thoughts and feelings. Obviously, this is a rather established way for some people to deal with these conditions, but I have never tried it. And being trained in political science, I started to link them to what would usually be understood as academic work.

In his work on firemen in the US, Matthew Desmond, drawing on a Bourdieusian conceptual apparatus, suggested that in the course of his participant observation his ‘body became a fieldnote’ (Desmond 2006, 392). Although Desmond talks about the embodied nature of a particular habitus, I found this remark intriguing with regards to my own experience. I do not mean to say that the somatic experience I went through would provide me with insights into the operation of certain rationalities I was looking into, in a manner parallel to Desmond’s research. It is rather that, first, my body became a site for the scars (personal jottings of sorts) which continue to remind me of the very real possibility of slipping into the zone in which a certain amount of physical pain poses as a preferred alternative to the mental anguish.

Autumn 2017, NYC

But Desmond’s remarks importantly speak to impressions which accompany depression for me.[6] I have not written in this document for quite some time. I am sitting in the NYU library. I feel on the verge of depression, like it is within my grasp, or rather the other way around. It is again this physical sensation, something that creeps around my lungs. If I am to describe the state in somatic terms, I resort to suffocating. I suppose this is as close as it gets to conveying the physical sensation that accompanies depression. In an article about the experiences of the illness, Andrew Solomon (Solomon 1998) describes his experiences with depression ‘as though I were constantly vomiting but had no mouth’.

Autumn 2017, NYC

I thought I would never experience this again. The intensity is interesting. I want to die.

In the following months, my condition improved quite significantly but in spring 2018, after I submitted the first draft of my Ph.D. thesis, I slipped into depression again. I was finishing my fellowship at NYU and I decided to take a trip to the West Coast before my US visa expired. Already before leaving, I was not feeling entirely okay but only upon my arrival to Seattle did I realise the severity of the situation. I was unable to focus on anything but the pain. I suppose the new, unfamiliar environment (by then, I felt quite like at home in NYC), coupled with the temporary lifting of the doctoral thesis burden and remembering some taxing personal issues I was going through in the autumn led to a renewal of the depressive state. My original plan was to go to Portland, Oregon and then to hike alone in a nearby national park. At one moment, I suddenly realised that I was quite likely to kill myself if I was to spend several days completely alone in the wilderness. I had never actually felt that I was so close to suicide.

Going back home to Prague a couple weeks later helped significantly but the progress was fragile. In late June, I attended a friend’s wedding in the countryside. At one point, I found myself in a kitchen staring at knives and imagining the physical sensation of plunging one of them in my throat and the resulting loss of blood, consciousness, and ultimately, life. Latour once asked ‘who, with a knife in her hand, has not wanted at some time to stab someone or something?’ (Latour 1999, 177). But for me the question really is who, with a knife in her hand, has not wanted at some time to stab herself?

Ideas like these do something to you. I keep being surprised when people tell me that they have never thought about suicide. For me, these contemplations have become perhaps not everyday, but still consistent parts of my inner life. Despite chemical treatment and psychotherapy, I still find myself thinking from time to time that perhaps killing myself would be preferable to continuing to coexist with these sensations.

These are curious states of being. As I write this, I remember being this person who has these states, these feelings, and these urges. And yet, they also do not really register as my own memories. This is why, on an analytical level, I find these mental states deeply intriguing. It is an opportunity to take a completely different position in and towards the world than is the norm for me. With the risk of exaggerating, I am inclined to say that during these depressive episodes, I do become someone else, someone whom I have a hard time recognising now when I remember these periods.

Illness, Academia, Fieldwork

With the advantage of hindsight, I realise that the experience of depression had profound influence on my academic work in several distinct regards. This very categorisation, this move of making my feelings neat, is a legacy of my university training: my being honed to identify and pin down social phenomena, label them, and put them into proper boxes. But this reflection does not change the fact that I came to think about these issues in such terms.

First, my alienation from myself was instrumental in drawing my attention to the existence of a multiplicity of incongruous perspectives in the social world we live in. Let’s consider what I wrote above: ‘I want to die.’ Perhaps due to biological imperatives, most human beings do not seek death. On the most basic level, I was forced to embrace that there are indeed people who want to commit suicide, and not in an abstract way: I – or rather a certain form of my self – was one of these people.

Considering that it was me who wrote this and who is yet still alive brings about quite curious ideas regarding different perspectives. I remember having these urges and feeling this pain but at the same time, they are completely alien and incomprehensible to my current self: I cannot relate to the person who had these impressions, although this person was actually me. This bifurcation, the experience of what I now perceive not only as an ‘abnormal’ urge to kill myself, but also as a completely unrelatable feeling, is quite destabilising. I cannot but acknowledge that I went through this state of mind, yet it is completely alien to me.

The distinctions between my ‘current’ self and my ‘depressive’ self, and the repercussions of these experiences, have meanings which go beyond the ‘emotional’. During the state of mind that I described above, I adopt a completely different outlook and my ontological and epistemological position shifted profoundly as my being in, and perception of the world underwent quite major transformations. During the worst depression I experienced, time basically stopped; I was sure nothing was to ever change; I could not imagine the pain would go away; and I could not focus on anything but it. I suppose this is not dissimilar from what Elaine Scary (Scary 1987) famously called ‘world-destructing pain’, although inflicted in a different way. I essentially went through a dissociation from my former self not only emotionally but also in terms of how I understand the qualities of this self and the environment I find myself in. What this means is that I somehow had to come to terms with the fact that there are things which are just on completely different planes of reality, impressions and experiences which are not reconcilable, and yet which coexist not only within the same physical space but even within the same person.

As a result, I believe my experience with depression led me to embrace particular academic approaches known under the label of ‘poststructuralism’, or at least it significantly facilitated this process. Although this claim might be a bit contentious, I would say that one of the main premises of what became known as critical scholarship is to recognise that there is a multiplicity of prisms, world views and ways of being in the world, and by extension that one’s position is necessarily just one contingency among many other possibilities. To really accept this is, I would say, actually a fairly hard task – it entails realising the confines of one’s positionality and its arbitrariness, something that is antithetical to the established notion of the self. Indeed, achieving this realisation is something that we seek to achieve through the laboured process of fieldwork that is supposed to bring us closer to the worlds of others.

I feel that depression significantly facilitated this process in my case. I do not doubt that I could have come to this experience through different means, as many others have. Nonetheless, it was the personal, even intimate experience with depression which made me attuned to alterity. This bifurcation – emotional, psychosomatic, epistemological – brought about by my mental illness made me aware of difference and otherness in a way that solely intellectual journey could not. As I am writing this, I cannot really relate to my own self from a few years earlier. What I am trying to say is not only that this realisation casts doubts on my ability to understand others (along the lines of ‘how could I if I can’t even comprehend my own thoughts’) but rather that it made me more open to the multiplicity of life experiences in the first place. I did not only comprehend that different people have different outlooks and worldviews; I lived this difference.

In a distinct sense, I think that my depression had a more concrete and specific impact on my scholarly conduct which I touched upon in the opening lines of this chapter. This transpired mostly during my doctoral studies, especially during my Ph.D. fieldwork. Not unimportantly, my mental condition made my stay in Israel/Palestine even more taxing. From several conversations I had with other researchers, activists and foreigners working in the region, I would argue that it is safe to say that the local situation is not exactly beneficial for one’s mental health. I guess it is redundant to say that already having issues in that regard does not exactly help.

As a result, my mental illness deeply impacted the way in which I conducted my fieldwork. There were several concrete instances in which my condition made me unable to take steps which I knew would be beneficial for my research but fairly detrimental for my well-being. I opened this chapter with one of these cases – I could not imagine living alone in a small, apparently boring community, without much social contact, even if it could have been beneficial for my research. Similar considerations also shaped my decisions several months later, after I spent some time in Ariel, a bigger settlement. My original plan was to spend the rest of my stay (about four more months) in Israel/Palestine in the settlement in order to further my ‘first-hand experience of everyday life’ in this particular field. However, I was struggling not only with alienation from my informants but also with reoccurring periods of mental instability – part of this chapter was written during that period as an attempt to offset these crises. I knew that I should stay in a settlement for academic reasons. But I also knew that I would be fairly miserable because of that. In retrospect, I am glad I chose to leave, even if I missed more opportunities for immersion.

Later I noted in my thesis that I simply ‘didn’t have what it takes’ (D’Aoust 2013) to fully immerse myself in the community I came to study. I still think this was the case. But I also realised there are limits to the lengths to which one should go in order to ‘have what it takes’, to be a ‘proper’ fieldworker, and to do the kind of research which would expose oneself to harm, physical or psychological. Based on my experience, I believe that these considerations should also matter when one tries to figure out the parameters of her stay in the field.

Later, my mental issues proved highly harmful for my academic productivity, something that is rather unsurprising to anyone familiar with these conditions. During the last year of my Ph.D. when I was a visiting student in New York City, my condition worsened for a few months, to a fairly debilitating extent. I could still function in terms of the everyday, less demanding activities, but I was not able to write. I did not think I would be able to finish my thesis if my condition persisted.

Nonetheless, in hindsight I can also see that my condition had imports which facilitated my research. In the course of my stay in Ariel, I was having a hard time really following the core ethnographic commitment and understanding the world of people I came to work with. I felt alienated from Israeli settlers with their conservative, right-wing, and casually racist remarks. Even more so, I could not really comprehend their mostly indifferent attitude towards the larger political conditions they were part of. In short, this constituted what I perceived as an ethnographic failure, a failure to really relate to the research participants.

It was only after I finished my fieldwork that I managed to harness empathy for the Israelis who move to the West Bank to live among the occupied Palestinians without giving much thought to the system they effectively maintain. First, I became wary of my own position as a foreigner who came to Israel/Palestine to get enough ‘data’ for a project, and then left once this task was completed. As such, the extractive nature of my stay on the one hand, and taking advantage of socioeconomic benefits by the Israeli settlers on the other, seem not so different. Also, as I discuss elsewhere, my attention to various material and visual practices that condition the everyday life in the settlements helped me to comprehend the epistemological, political, and ultimately ethical gap between the settlers’ experiences and the nature of Israeli occupation.

But I would also say that the attitude shift vis-à-vis the settlers on my part was enabled by my previous close exposure to Otherness – not political difference but the alterity that occurred between different states of me. It was, in a way, perhaps the ultimate ethnographic experience, an experience that made me more receptive towards other ways of thinking, feeling and being, albeit only after I finished my fieldwork and could better reflect on the encounters I had in the settlements. I don´t think I could understand the settlers to a similar extent, seemingly so different and detached from me, had I not encountered difference and detachment from and within myself before.

Illness and Failures

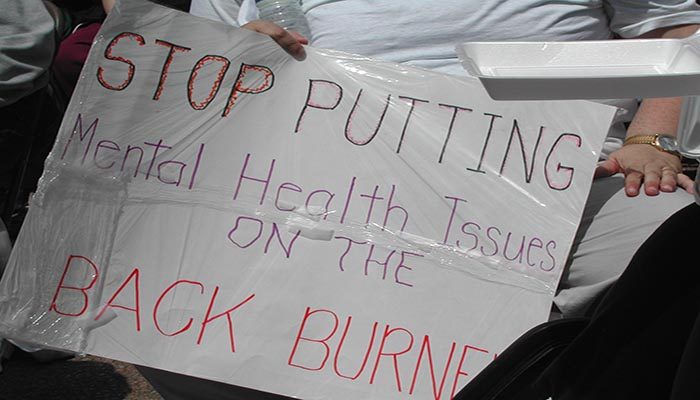

There is an infamous tendency to treat mental illnesses as individual insufficiencies, as particular failures of will. This is naturally not the kind of failure I want to entertain here. The existing research clearly shows that one cannot conceive mental health issues as personal shortcomings, something that I suspect the readers of this particular volume are aware of. And there is now more than enough evidence that higher education is a particularly hostile environment for people with mental illnesses – and that academia even induces those.[7]

The failure that I want to briefly talk about here is essentially two-fold, and to some extent consists more of repeating what others have expressed much better before me (see e.g. Hartberg 2019). First is the absence of institutional support for people in academia struggling with various mental illnesses (which reflects the situation in our society at large). Although there are some consultation services available, they are usually insufficient to really provide support in the midst of the current mental health epidemics. Frequently, these concerns are even more pressing during fieldwork when the researcher finds herself away from what (hopefully) had become an academic home where one can find refuge among colleagues and friends. In the field, the pressure of research is thus combined with the absence of social and institutional safety nets.

Second, failure is a somewhat more specific articulation of the first one. It is, very much in the spirit of this volume, failure to publicly discuss how these and similar experiences and issues impact our scholarly conduct. By now, it has (thankfully) become standard in the academic works based on fieldwork to attend to one’s positionality and how it plays out in the field. Nonetheless, to my knowledge there is a lack of works which would attend to mental health in relation to fieldwork (for an exception see Tucker and Horton 2019). As I discussed in this chapter, these issues are crucial, not only in terms of individual wellbeing but also in making our knowledge claims. If we accept that the research experience is an embodied one, we need to attend to these aspects as well: for many, mental issues are part and parcel of the stay in the field.

Conclusion?

After Katarina read the first draft of this chapter, she asked me what I was trying to achieve by writing all of this, ‘what am I hoping to get from publishing the chapter’. When I was thinking about this question, I realised that the most honest question is rather selfish. As I wrote in the introduction, I sought to adopt detachment from my condition: over the last few years, I found out that writing down my impressions and taking a certain distance, turning my depression into (yet another) problem to be probed academically, helps me to better cope with it. Doing so does not allow me to overcome the condition altogether but it is useful for making sense of this experience. It felt that publishing what I wrote over the last several years is a logical next step, a step which would further cement this attitude.

But beyond this, in this chapter I sought to caution against disregarding the importance and salience of ‘personal’ and health issues for the academic conduct, practice and knowledge production. Not only do my experiences show that the academic is intimately related to other dimensions of one’s life, they also demonstrate that we need to weigh academic calculations with concerns for our wellbeing, perhaps especially in the context of a taxing stay in a foreign and strange land of ‘fieldwork’. And I also hope that in discussing these issues, this chapter can be useful for people facing similar problems, although the pessimistic me suggests that it might be wishful thinking.

I am sceptical towards the promise of this text because I recognise that it is easy for me to say these things now, when I have not experienced a depressive episode in a while. The following (and concluding) paragraphs that I wrote more than a year ago show that my current stable state is far from guaranteed, and that its deterioration can have a serious impact.

New York City, May 2018

Andrew Solomon (1998) finishes his piece on coming to terms with depression by noting that ‘I cannot find it in me to regret entirely the course my life took’. As I read it, I remembered that I uttered almost the exact same words some 13 years ago, in conversation with a friend after I had undergone my first wave of estrangement from myself. Perhaps this piece is a reiteration of this sentiment: what I wanted to show here is that my current self and my depression cannot really be separated, and in many regards I am glad for the forms that my self and, with Solomon, my life at large obtained.

But at the same time I am not sure if the price was not too high. My depression was (or rather has been, and perhaps will be again), after all, extremely painful. And they proved to be disruptive for the lives of people around me, in some cases they served as a large part of the reason why people I considered close became estranged from me. This is why I feel that writing all of this is also, or perhaps mostly, an effort to be able to cling to this analytical self the next time I feel my sanity waning and dissolving. But I am afraid it might not work. Because with every new seizure, I feel my resolve to struggle against these disruptions fading a little bit more. I am just tired. I will stop now.

*The author would like to thank Katarina Kušić and Františka Schormová for their comments on previous versions of the chapter. All that you dislike about this text is my fault though.

Notes

[1] Curiously, in this regard the present text and the personal effort to make sense of my condition that animates it somewhat parallels the ethnographic project of learning from a close encounter with ‘the field’, yet seeking to maintain a distance from it at the same time. I am grateful to Katarina Kušič for pointing this out to me after reading an earlier draft of the chapter.

[2] I re-read this passage more than two years after I wrote it. I remember the feeling, almost psychosomatic, that I had when writing it. It was in the middle of my doctoral fieldwork which I was conducting in Israel/Palestine, and I was deeply frustrated with the scholarly literature which seemed so detached from my experience. As I discuss below, I also felt unwell mentally.

[3] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/depression#medicalDictionary

[4] This whole section was written in spring 2016.

[5] Lag BaOmer is a Jewish holiday which is in Israel traditionally celebrated by lightning bonfires and barbecuing.

[6] The following part was written in autumn 2017 when I was a visiting Ph.D. student at New York University.

[7] For example, a recent study (Levecque et al. 2017) found that 32% of Ph.D. students are at risk of developing a mental disorder, mostly depression, a rate much higher than other comparison groups. Importantly, this applies not only to early career researchers, but senior staff (see e.g. Weale 2019) as well as non-research students. With regards to the latter, according to research conducted among the UK students by All Party Parliamentary Group on Students (All Party Parliamentary Group on Students 2017), one third of the respondents reported having suicidal thoughts at some point.

References

All Party Parliamentary Group on Students. 2017. ‘APPG Briefing: “Lost in Transition? – Provision of Mental Health Support for 16–21 Year Olds Moving to Further and Higher Education.”’. http://appg-students.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/APPG-on-Students-December-Mental-health-briefing.pdf.

D’Aoust, Anne-Marie. 2013. ‘Do You Have What It Takes? Accounting for Emotional and Material Capacities.’ In Research Methods in Critical Security Studies: An Introduction, edited by Mark B. Salter and Can E. Mutlu, 1 edition, 33–36. London and New York: Routledge.

Desmond, Matthew. 2006. ‘Becoming a Firefighter’. Ethnography 7 (4): 387–421.

Hartberg, Yasha. 2019. ‘Depression and Anxiety Threatened to Kill My Career. So I Came Clean about It’. The Guardian, September 10, 2019, sec. Society.

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/sep/10/depression-and-anxiety-threatened-to-kill-my-career-so-i-came-clean-about-it.

Latour, Bruno. 1999. Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Levecque, Katia, Frederik Anseel, Alain De Beuckelaer, Johan Van der Heyden, and Lydia Gisle. 2017. ‘Work Organization and Mental Health Problems in Ph.D. Students’. Research Policy 46 (4): 868–79.

Scary, Elaine. 1987. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Solomon, Andrew. 1998. ‘Anatomy of Melancholy’. The New Yorker, January 4, 1998. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1998/01/12/anatomy-of-melancholy.

Tucker, Faith, and John Horton. 2019. ‘“The Show Must Go on!” Fieldwork, Mental Health and Wellbeing in Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences’. Area 51 (1): 84–93.

Weale, Sally. 2019. ‘Higher Education Staff Suffer ‘epidemic’ of Poor Mental Health’. The Guardian, May 22, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2019/may/23/higher-education-staff-suffer-epidemic-of-poor-mental-health.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Fieldwork, Feelings and Failure to Be a (Proper) Security Researcher

- Fieldwork and the Coronavirus Pandemic

- What Might Have Been Lost: Fieldwork and the Challenges of Translation

- Fieldwork, Failure, International Relations

- Failing Better Together? A Stylised Conversation about Fieldwork

- The Limits of Control? Conducting Fieldwork at the United Nations