On March 6th, 2015, the US Secretary of State presented Captain Niloofar Rahmani, the first Afghan women to serve as a fixed-wing air force pilot, with the International Women of Courage award. Rahmani’s story elevated her onto the international stage and was told across global news outlets and also by the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). Her fame came at a personal price, with death threats from the Taliban directed at her and her extended family, culminating in Rahmani being granted asylum in the US in 2018. Rahami herself has accused the West of ‘making her a target by using her as a poster girl for women’s rights and then abandoning her’. The global media coverage following the successful completion of training in 2016 is therefore worth examining.

Much has been written about how the emancipation of Afghan women has been key to Western justifications for the continued intervention in Afghanistan. What has received less attention, is how these stories have permeated beyond the West, for example in India where women officers from the Afghan National Army and Air Force took part in a 21-day military course at Chennai’s Officers Training Academy. In this article, we examine how Afghan women have been invoked in geopolitical imaginaries from India to NATO members, specifically how the military achievements of Afghan women have functioned as a part of an emancipatory narrative.

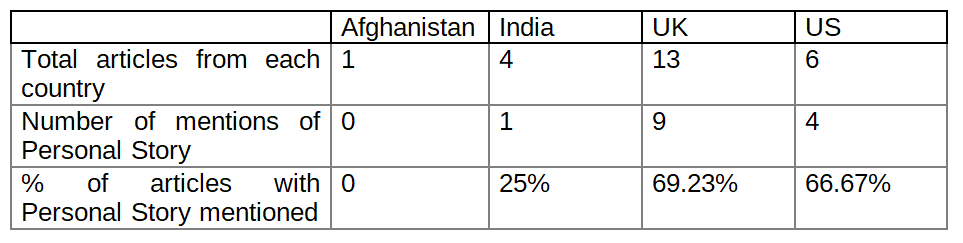

Rahmani is not the only Afghan women to qualify as an air force pilot, even if she is the first to qualify as a fighter pilot in 2016. Col Latifa Nabizada became Afghanistan’s ‘first woman of the skies’ in 2013 when she piloted helicopters in the Afghan air force, and Capt. Safia Ferozi began to fly transport planes in 2016. It is also worth highlighting that women remain significantly underrepresented in the Afghan National Forces at under 1%, in comparison to the NATO average of 10.9% and in India the army has 3% women, the Navy 2.8% and the Air Force 8.5% (it was only in 2015 that India opened up fighter pilot training to women). The coverage of these women and their stories then belies the reality of women’s continued underrepresentation in both Afghanistan, the US, UK and India. In order to address this research puzzle, we compare the coverage of the few Afghan women air force pilots, including Rahmami, by the media from 4 different states: Afghanistan, India, and the US and UK. This research analysed a total of 24 English language newspaper articles identified using LexisNexis from 2013-2018. We used discourse analysis to identify instances where the personal story was covered. We also focused our analysis on differences in media coverage across the political spectrum because this has been a determinant of public support for the war. For example, in the US, people on the right of the political spectrum have been more like to support the intervention in Afghanistan. Each article was divided into three broad categories of left, centre and right using the Pew Database in the US, YouGov for the UK and public alignment and ownership for newspapers in India to identify these. For Afghanistan, only one newspaper article was identified as relevant so we excluded it from our analysis of the political spectrum. The fact that there was only one Afghan-based news piece could be a result of the limited media available in the English language. It could also indicate that this was not a topic deemed newsworthy in Afghanistan, although further research would be needed here.

Afghanistan in Perspective

One of the justifications for the 2001 intervention in Afghanistan was based on the pretext of ‘white men saving brown women from brown men’. Laura Bush invoked this in her address following the start of US-led Operation Enduring Freedom in 2001:

Civilized people throughout the world are speaking out in horror — not only because our hearts break for the women and children in Afghanistan, but also because in Afghanistan we see the world the terrorists would like to impose on the rest of us.

The emancipation of Afghan women, therefore, served to supplement the initial justification of the war as a necessary defensive action to protect American people following the attacks of 9/11 when this was called into question. It was deeply orientalist, setting the world in a manner where the West is the ‘masculine saviour’ while Afghanistan is the ‘feminine other’ in need of saving through the logic of ‘masculinist protection’. As a result, many in the West still see a single picture of an Afghan woman and automatically assume it is someone who is oppressed and suffering and therefore requires help from the international community.

The centrality of Afghan women to Western involvement in Afghanistan has a long history dating back to the early 20th century. The inconsistency in when and how their stories are invoked supports the contention that Afghan women have ‘become implicated in the geopolitical manoeuvrings of powerful global actors’. For example, during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan (1979-1989) efforts were made to emancipate women. Yet when the US-backed mujahidin came to power in Afghanistan in 1992 it oversaw one of the worst periods of human rights abuses the country had seen. Then when the Taliban overthrew the mujahidin in 1994 severe restrictions on women’s rights were put in place including on their freedom of movement. The preoccupation of the Western interveners with ‘rescuing’ Afghan women, therefore, has both an imperialist and political implications.

This troubled history, as well as the use of gendered justifications by states to pursue their own foreign policy goals, does not exclude the neighbours of Afghanistan and their relationship, for example, India. Afghanistan and India as neighbours have had a longstanding relationship in terms of culture, commerce and between the people of the two states. The relationship almost ended during the Taliban regime, and after the regime fell, India immediately opened its embassy in Kabul. Today, there are multiple reasons for India to maintain its relations with Afghanistan. One of the main reasons is to combat the influence of Pakistan in the region. As a result, India is the largest provider of aid in South Asia to Afghanistan. The Indian government has also used the idea of the protection and improvement of the standard of living of the people of Afghanistan, particularly women to assert more influence in the region. For example, as we go onto discuss, India agreed to train women officers from the Afghan Air and Armed forces, despite the fact that India maintains a combat ban for women stating that the men in its forces are not ‘yet mentally schooled to accept women officers in command’.

The Personal Is Political Is International: Invoking Afghan Women’s Stories

Following the end of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission in Afghanistan in 2014, the Resolute Support Mission was launched by NATO in January 2015. The same year that Rahmani’s stories came to global prominence. Resolute Support is a non-combat operation to transfer security to Afghan National Defence and Security Forces, including a focus on training. Rahami began training with the US airforce at in the same year. Since this time, security has deteriorated in Afghanistan. In the first 6 months of 2018 alone, a total of 1,692 deaths have occurred including 157 women. This death toll and the status of Afghan women has been used as a justification for maintaining NATO’s presence in Afghanistan by NATO itself, but also by organisations such as Human Rights Watch who have argued that ‘NATO shouldn’t abandon Afghanistan’s women’.

Our analysis here (see Table 1) finds a predominance of personal stories in media coverage of Rahmani and the other pilots in the UK and US, both prominent NATO members. The personal stories focus on the plight of Rahmani, rather than her agency, for example, having ‘to spend [her] early life as a refugee in Pakistan after the Taliban seized control of Afghanistan in 1996’ and her aspirations, for example, ‘ever since she was a little girl she had dreamed of becoming a pilot’. As an article in The Times describes:

She was playing chess with her brother, Omar, in 2010 when an advert came on the television calling on women to enlist in the Afghan armed forces. Rahmani’s family told her it was too dangerous. “This is Afghanistan,” her mother said. “Society is not ready to accept working women, let alone women in uniform.” Her best friend laughed at the idea. “In Kabul the only things that fly are pigeons and Americans,” she scoffed. Eventually Rahmani’s father agreed as long as it was kept secret from the rest of the family, even her younger siblings. They were told she was at university.

Afghanistan’s one piece of news coverage is factual with no personal stories included. The coverage in Indian media, in contrast to that in the US and UK, focuses on India’s supporting role and the wider significance in terms of the live debate on women in combat, rather than Rahmani herself. In 2020, for example, the Indian Supreme Court ruled women were ‘not ready for combat’, while the UK had announced a lifting of combat exclusion ban for women in 2016 and the US in 2015 settling the debate. In one of the articles in The Hindu Times, a woman officer raises the contradiction of a combat ban and a role which finds them training women of another country to take part in active combat missions:

Though they are not allowed in combat roles, the exposure of some members of the Afghan delegation to combat means that their trainers too, learn from them. “Yes, I think we can learn from them. I think the women of the Indian Army should be given a fair opportunity in combat roles. If Afghan lady officers can, surely we can too,” said Maj. J.R. Sanjana of the OTA (Officers training academy).

Table 1: Personal stories in media coverage

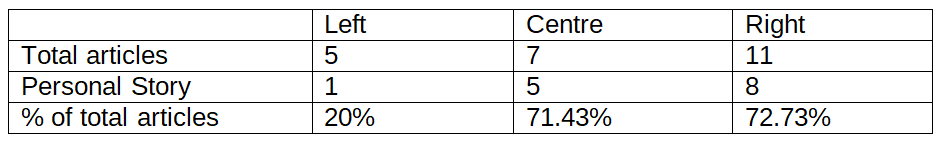

We also examined the political leanings of newspapers to see if this had a determining effect on the likelihood they would focus on Rahmami’s personal story. If the plight of Afghan women was a central justification for the 2001 intervention and given those on the right of the political spectrum are more likely to support the war in Afghanistan, then we would expect right-wing newspapers to focus more predominately on personal stories.

Table 2: Political leaning of articles/personal story

The use of personal stories in media coverage is particularly interesting here because the focus on a personal narrative helps to support the contention that the intervention in Afghanistan has supported the ‘emancipation’ of Afghan women in the face of evidence which shows otherwise. Decades of war have left Afghanistan the ‘worst place in the world to be a woman’. NATO’s own public diplomacy strategy has utilised Afghan women’s narratives, for example, in a 2014 social media initiative titled Return to Hope which sought to tell ‘NATO’s story of Afghanistan’. As Katharine A. M. Wright argues:

NATO’s approach to digital diplomacy is not just concerned with selling the alliance’s ‘hard power’ capabilities and that the alliance takes a more sophisticated approach to reach target audiences. The focus on individual narratives, even when discussing broader issues – such as women’s rights – serves to depoliticize NATO’s story of Afghanistan. This draws attention to the necessity of contextualizing individual narratives within the wider framework in which they are presented.

We should, therefore, be cautious about the heavy reliance on personal stories to tell any story, but particularly when they predominately focus on one group, in this case, Afghan women. The preoccupation of the Western media with Afghan women is nothing new and Vera Mackie has argued that the icon of the veiled Afghan woman in this coverage has come to stand ‘for the people, the land, and the nation-state of Afghanistan’. As Judith Butler argues it is necessary to demonstrate caution before championing the ‘liberated’ faces of these Afghan women and ‘to ask in what narrative function these images are mobilised’. The focus on a veiled Afghan woman in a pilot’s uniform is a new addition to this narrative, but one which fits with NATO’s move in 2015 to offer training and support to Afghan armed forces, rather than engaging in a combat mission. Here Rahmani’s and the other women’s stories comes to represent progress and becomes symbolic of emancipation, through women’s full integration into the armed forces. The projection of this narrative is interesting when considered against the wider context given it came just a couple of years after the US had lifted their combat ban and a few years before the UK would itself do so.

Our Enemy, the Taliban: ‘White Men Saving Brown Women from Brown Men’

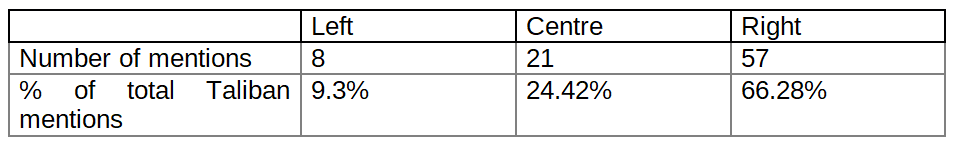

The Western intervention in Afghanistan has been justified along with the War on Terror within the logic of masculinist protection. Both Bush and Obama, for example, drew on a particular gendered ‘villain–victim–hero’ discourse in order to gain support for their actions across the globe. Through their speeches they constructed this ‘hero-villain’ relationship as unequally gendered, with the ‘hero’, the US, taking a hegemonic masculinized position as ‘civilized, virtuous, just and peaceful’, while the subordinate masculinised villain, the Taliban, was ‘uncivilized, cruel, unjust, and violent’. The rest of the world became ‘passively dependent’, ‘unable to protect themselves’ or feminised. The result is also deeply racialised and speaks to Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s notion of ‘white men saving brown women from brown men’.

Our sample of newspaper articles demonstrates that although the focus was on Rahmani and Afghan women pilots, the Taliban were mentioned most significantly in those on the right of the political spectrum, with a far less focus on left and centre leaning publications. If those on the right of the political spectrum are more likely to support the war in Afghanistan then it follows that their view of Rahmani’s success would be predicated as an achievement which would not have been possible under the ‘villain’ Taliban. The narrative, therefore, focuses on how the ‘heroic’ West has ‘saved’ the Afghan women ‘victims’ from their

Table 3: Number of times ‘Taliban’ is mentioned in articles and their political leaning

Conclusions

The research presented here reinforces the existing postcolonial and feminist scholarship on Afghanistan which has drawn attention to the predominance of Afghan women in the framing of the intervention in Afghanistan in the West. Our findings also suggest that this is the case beyond the West, in neighbouring states such as India. This study provides a small snapshot of this coverage around one particular event, the first women to become Afghan Air Force pilots and further research is needed. However, our findings do suggest that the coverage in India, while gendered, focuses less on personal narratives and more on India’s support to Afghanistan and is understood within the context of India’s ongoing debate on whether to lift their combat exclusion ban for women. Afghan women are undoubtedly caught between geopolitical imaginaries of Afghanistan.

Our study also suggests that the ‘villain-victim-hero’ has shifted as the NATO intervention has moved from combat to training and support. This has led to the presentation of Afghan women air force pilots, such as Rahmani, as evidence of this emancipation. If we contextualise this against wider developments in the US and UK to open combat positions to women in recent years, then we see how Rahmani’s story supports a wider purpose which effectively militarises women’s emancipation.

Ultimately, the focus on personal stories in much of the media coverage obscures the uncomfortable truth of the dire situation for Afghan women and their significant underrepresentation in Afghan armed forces. As Rahmani herself has stated her story has been instrumentalised to sell a narrative of progress and she has been left abandoned by the West.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Afghan Peace Talks, China, and the Afghan Elections

- Opinion – Why Women’s Rights in the Gulf Matter for Afghanistan

- The Afghan Peace Agreement and Its Problems

- Opinion – #arrestlucknowgirl: A Reminder of India’s Postcolonial Desire to Control Women

- What Happened to the Afghan Peace Talks?

- The Geopolitical Influence of India And Indonesia in SAARC and ASEAN