Despite over 30,000 North Koreans resettled in South Korea, the economic integration of these arrivals remains poorly understood. North Korean refugees have an unemployment rate nearly 7% higher than South Koreans and those that do work average eight more hours a week than their South Korean counterparts for roughly two thirds the wages. Moreover, 75% work irregularly or in part-time positions. Employment struggles are compounded with challenges with social integration, due to post-war cultural divides and arrivals associated with negative aspects of North Korean life.

Interestingly, the employment of North Korean defectors may fall along gendered lines. A survey of North Korean defectors and South Koreans and found that it is commonly believed that North Korean women integrate faster into South Korean society because they can find jobs more easily. Other studies find that male defectors have less experience working in businesses and commerce, which may make adapting to life in South Korea harder. In North Korea, women gain experience by working in stores, as entrepreneurs, and in the black market, whereas men often are forced to work for government-run institutions.

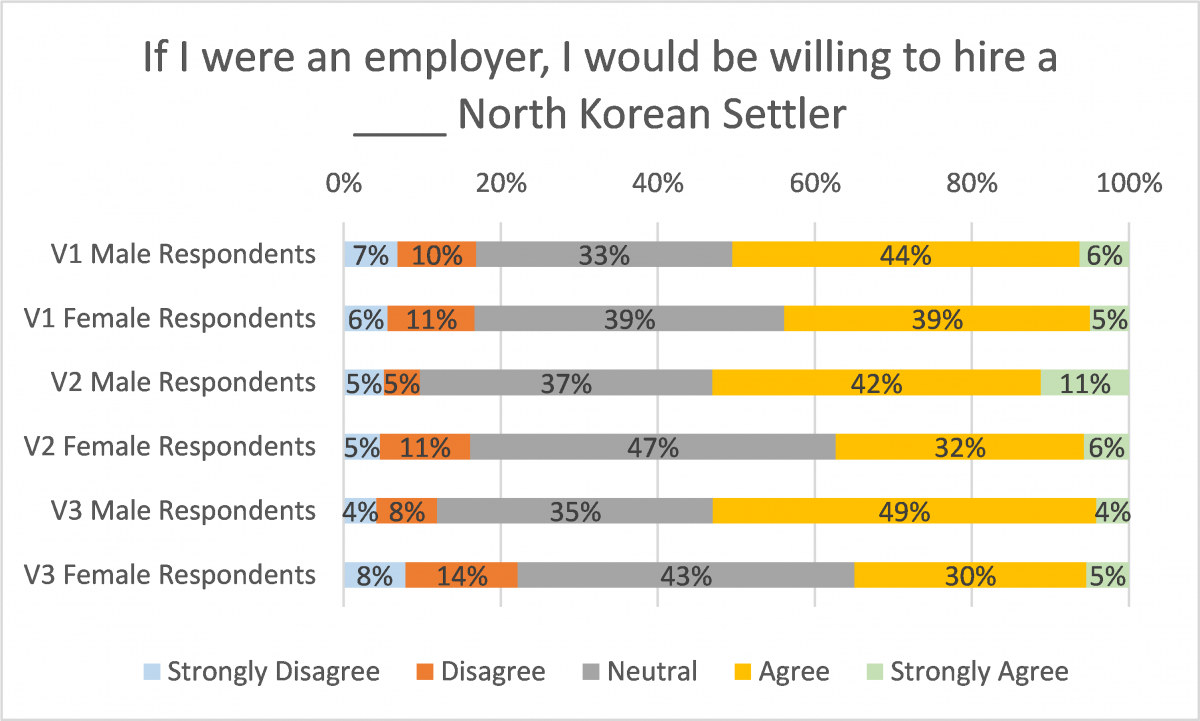

In order to study South Korean perceptions of defectors, we conducted an experimental web survey through Macromill Embrain, using quota sampling by age, gender, and region based on census data. 1,111 respondents were randomly received one of three versions of a statement and evaluated the statement on a five-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The versions were:

Version 1: If I were an employer, I would be willing to hire a North Korean settler.

Version 2: If I were an employer, I would be willing to hire a female North Korean settler.

Version 3: If I were an employer, I would be willing to hire a male North Korean settler.

The figure below shows the survey results broken down by gender. Overall, nearly 50% of respondents were willing to hire a North Korean settler. However, when dividing by gender there are clear differences in perceptions. Regardless of the version, female respondents were less likely to hire a North Korean. Most tellingly, female respondents were 18% less likely hire a male North Korean than male respondents.

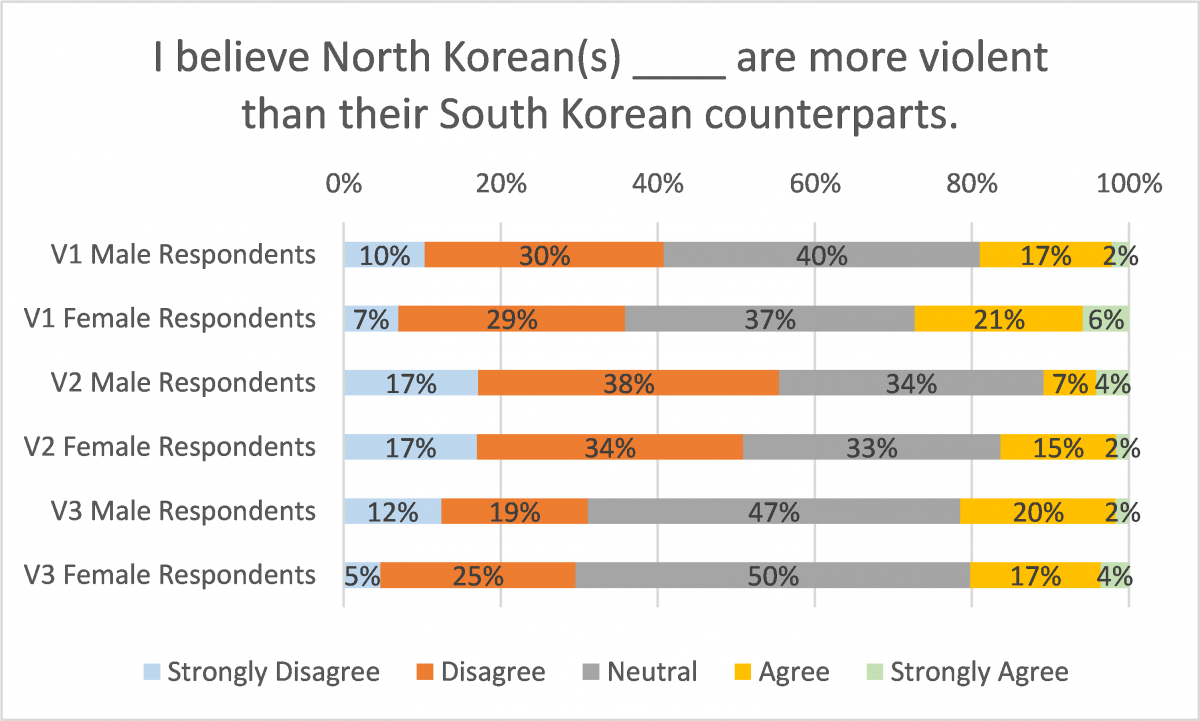

One potential reason South Koreans are hesitant to employ North Koreans is because they believe that North Koreans are violent. Factors such as the prevalence of bribery, organized crime, and theft in North Korea may increase negative perceptions of defectors. Moreover, nearly half of North Korean defectors experienced violence caused by North Korean authorities, which may induce later violent behavior or PTSD in defectors.

In order to evaluate perceptions of North Koreans as violent, which could explain reluctance to hire North Koreans, respondents also were asked to evaluate another randomized statement on the same five-point scale as before:

Version 1: I believe North Koreans are more violent than their South Korean counterparts.

Version 2: I believe North Korean women are more violent than their South Korean counterparts.

Version 3: I believe North Korean men are more violent than their South Korean counterparts.

The figure displayed below shows the survey results broken down by gender. We find that all respondents are most likely to agree with version one, that North Koreans are more violent than South Koreans and least likely to agree with version two, that North Korean women are more violent than South Korean women. Female respondents were 8% more likely to believe that North Koreans are more violent than South Koreans overall, and approximately 5.5% more likely to view North Korean women as violent than South Korean men. Regression results (not shown) find a strong relationship between viewing a North Korean as violent and being unlikely to hire a North Korean, even when controlling for age, gender, education, political ideology, and income.

Overall, female respondents were more likely than male respondents to perceive North Koreans as violent, and they view men as more violent. Female respondents may fear North Korean men more than women due to reports of human rights abuses, especially against women, in North Korea. For instance, Human Rights Watch reported that North Korean officials are permitted to assault women and face little, if any, consequences. The already widespread social acceptance for sexual violence in South Korea coupled with existing stereotypes of North Koreans may trigger concerns for women’s personal security.

Although it is a positive sign that most respondents did not identify North Koreans as more violent than their South Korean counterparts, the high number of neutral responses could indicate a social desirability bias. Additionally, future surveys would likely benefit from asking about defectors specifically rather than generalizing perceptions of all North Koreans, as differences may exist in perceptions between the two groups.

The South Korean government could address some of the underlying causes of defectors’ struggles. Firstly, the assistance the South Korean government offers in areas such as housing, job training, and education, yet when spread amongst thousands of recipients, the funds allocated are clearly not enough. The current five-year limit on assistance may also be too short, but rather than simply extending financial aid, the South Korean government could also survey defectors to see what areas they find most challenging, and channel resources to where help is most needed.

The South Korean government already gives incentives to businesses to hire North Koreans, including subsidizing up to half of each defector’s pay for four years. Despite this policy, less than half of South Koreans are willing to hire a North Korean. Businesses promised aid in return for hiring North Koreans may feel resentful if that money never appears. Our survey also found that male South Koreans were more willing to hire any North Korean, regardless of gender, than female South Koreans were. This may be because male South Koreans are more likely to be in upper-level positions or other hiring roles than female South Koreans, rather than a deeper perceptual difference by gender.

Despite the considerable amount of assistance which the South Korean government provides for North Korean defectors, many still face discrimination in their everyday lives. Consequently, the government must approach the situation in an alternative manner. For instance, the government should pinpoint areas where aid to defectors is needed most, as blanket policies have proven insufficient in the past. Finally, these results show that deep divisions exist along gendered lines in South Korean society, and these divisions worsen when defectors are added to the equation. Therefore, policies to help improve defectors’ situations must also address issues of gender.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – South Koreans Support Unification, But Do They Support Integration?

- Opinion – The Potential of Strategic Ambiguity for South Korean Security

- The Emperor’s Dignity: A Candid Primer on Korean Reunification

- The Danger of Passive Containment and Ignoring North Korea

- Surveying Opinion on Withdrawing US Troops from Afghanistan and South Korea

- A Unified Korea: Good for All (Except Japan)