Alongside poststructuralist approaches, critical security studies has been at the forefront of engaging the visual in International Relations (IR). Rune Andersen and Juha Vuori’s (2018) edited volume on visual security studies (VSS) is testament to this and brings various disciplines together to focus on (in)security and war. Acknowledging that we live in the ‘age of the image’ (Williams, 2018), IR scholars are turning to the visual in various, innovative ways. Andersen and Vuori (2018) point out three ways the visual comes into international security: visuality as modality, where images represent and signal security; as practice, where images construct (in)security; and, as method, where images are a research tool used to make security visible. The first two are the most common way of engaging images in IR: treating images as artefacts through which we come to know, make sense of, and act in the world; through which we ‘see’ and ‘do’ international politics.

These works emerge from the pictorial and aesthetic turns. Examples of this type of work include: Lene Hansen’s work on the Muhammad cartoon crisis (2011) and comic books engaging the Bosnian War (2017); Axel Heck and Gabi Schlag’s study of a TIME magazine cover and the Afghanistan war (2013); Roland Bleiker’s work on representations of HIV/AIDS (Bleiker and Kay, 2007)and the dehumanisation of refugees (Bleiker et al., 2013); Vuori, Andersen, and Guillaume’s (2015; 2016) semiotic, chromatological approach, which argues that colour enacts and makes security intelligible; Simone Molin Friis’ (2018) combination of digital ethnography and visual approaches to study militant imagery; Helen Berents’ (2019) work on images of dead children and the ‘telegenic dead’; Constance Duncombe’s (2019, 2020) work on images, emotion, and social media; my work on the use of posters (2019) and comic books (2020) to constitute and/or contest gendered-sexualised-racialised (in)security; and Megan MacKenzie’s study of soldier-generated illicit images, which shows how they are “central to, and reinforce aspects of, military band of brother culture” (2020).

In the less common but growing strand, visuality as method, Sophie Harman’s (2019) pathbreaking work, which I reviewed for E-IR and Disorder of Things, uses narrative feature film as a “method of seeing those who are invisible from politics, policy, and global health research”, challenging how we ‘see’ international politics and global power structures; Sara Särma (2018) uses collage to rethink the spatiality of international politics; Debbie Lisle and Heather Johnson (2019), and Roland Bleiker (2019) use their own photographs to sight, trouble, and rethink (in)security; Cynthia Weber (2011) and William Callahan (2015) use film as research output; and Benjamin Dix, engaging with issues like conflict, migration, and asylum, works with marginalised individuals to produce comics (positivenegatives.org).Works from all three (not always separable) ‘strands’ of visual politics, as well as the plethora of others not mentioned, form part of ongoing and productive discussions about how we approach the visual ontologically and methodologically. In other words, what images ‘do’ and how we use/study them.

There is no end to the ways that the visual can be brought into the study of (international) politics. The studies I have mentioned above are mostly qualitative. That is not to say a quantitative approach cannot be used: there are merits to quantitative and mixed methodologies that allow scholars to ask different types of questions. A quantitative approach may, for example, be better suited to identifying different patterns in large data sets of images. Bleiker et al. (2013) use content analysis to analyse newspaper coverage of asylum seekers, which opens space for different, more nuanced, qualitative study of those images. This piece, therefore, should serve as one of many (many!) ports of departure that visual venturers can leave from. Better yet, it will take the mystery out of doing visual scholarship and inspire methodological play in a robust way that avoids just ‘adding images in because it’s trendy now’.

Through the empirical case of the pink triangle and US AIDS activism, I will present some tools for those looking to engage with visuals in their work. What follows stems primarily from my own work on the visual. It should not be read as a blueprint, definitive ‘how to’ guide, or a manifesto outlining what visual politics ought to be. It is unproductive to police the boundaries of VSS and visual methodologies: a pluralist approach is key to understanding the complexity of the visual (Bleiker, 2015) and using visuals as scholarly output can help de-centre the epistemological priority given to texts in academia (e.g., essays, articles). Visual scholars agree that the visual is irreducible to and cannot adequately be captured through written/spoken words. Nonetheless, we commit to trying to capture their politics in the words we write; inevitably, we will always fail. This is a hard tension to negotiate. The most exciting part of VSS is that it is a moving target: new and innovative ways of using the visual as method and/or empirics are always emerging.

Theorising the visual: A tripartite approach

Drawing on poststructuralism, I have engaged with the visual as part of discourse and, thus, as a site through which to see (in)security (Cooper-Cunningham, 2019, 2020). I have engaged images as both representing and constructing (in)security; as modality and practice. Using a poststructuralist-inspired approach has implications for how one theorises and engages the visual. How images ‘speak’, what they ‘do’, and their ontological status is an ongoing debate in visual politics. Like many visual scholars, I draw on Roland Barthes (1977) who argues that the meaning of an image cannot be pinned down definitively, that images do not have a single universally received message, and that images cannot be understood as telling a story in and of themselves. How you and I interpret an image is not necessarily the same because we draw on different personal experiences and knowledge to read it.

We, therefore, need to include other texts and images in our analysis because these help to attribute meaning to the image(s) under study; these are the ‘stock’ that we draw on to interpret images(Hansen, 2011). Not only are other texts and images important, we must also consider how an image is circulated, how it is used, and how it is spoken about: does it cross borders, get used in protests, or capture widespread attention for instance? These all affect the arguments we can make of an image, how they might be read, and what political status they’re attributed: when a particular visual motif is used in protest marches, for example, it acquires a different status than if it were not. Recently, critical scholars have moved to engage with the aural, the sounds that accompany (moving) images, and how this imbues them with meaning (Baker, 2020; Malmvig, 2020). A simple way of experiencing the powerful visual-aural, visual-textual interaction, the effect of one on the other, is to turn off the sound/visual on your favourite film scene and to recall when you’ve encountered artwork in a gallery and interpreted it very differently from the explanatory caption.

My theorisation of and relationship with the visual emerged from a theoretical-empirical problem. Theoretically, how feminist scholars think about silence. Empirically, how British suffragettes resisted the oppressive silencing practices of a government seeking to ensure women’s exclusion from public political fora. Working through the case of British suffragettes’ acts of resistance against the patriarchal system, I noticed that they used a combination of words (written and spoken), images (posters/postcards), and embodied action (hunger-striking) to contest and undermine the dominant narrative that women were apolitical, incapable of politics, and that their participation in British politics through the vote would undermine (gendered) order and bring about chaos.

To understand what was going on in this case, I brought together Lene Hansen’s (2000: 300) argument that we should bring in the visual and the bodily as additional epistemological sites where (in)security can be announced with Karin Fierke’s (2013) work on ‘acts of speech’, communication without words. From there I developed what I call a ‘tripartite model’ to study (global) politics—particularly security—where one brings in words, images, and bodies into their analysis simultaneously. Put simply, this means that we shouldn’t just look at the written/spoken words (e.g., government documents, press, activist statements) around political issues (e.g., state homophobia, wartime rape) because sometimes there aren’t any or they are not the primary way of announcing (in)security. Instead, for a whole host of reasons, there might be (imposed or chosen) silence, or insecurity is announced in another way. For example, through hunger striking, silent protest, making and circulating online memes, taking a dangerous 100mile boat ride, self-immolating. Silence does not mean absence, that nothing is going on[1].

Insecurity might be articulated in other ways: through the visual, for example. In this sense, I theorise communication as something more expansive and complex, enacted through and exceeding words: words, images, bodies ‘speak’ together. That also means silence isn’t necessarily just vocal/textual: it encompasses the visual, too. Just because there aren’t any words articulating (in)security doesn’t mean there aren’t images doing the work. Neither the visual nor words have primacy: they must have equal analytic footing. Scholars must think about other epistemological sites through which we can understand and explore (international) political phenomena. When we are speaking of issues with such high stakes as security, which can often be (constituted as) existential for some individuals and collectives, it is important to look at a broad range of materials.

Pink Triangles

To ground this discussion and put some empirical flesh on the theoretical bones above, I turn to the pink triangle, which was marked on (suspected) male homosexual bodies during World War II by the Nazis, and the ‘Silence = Death’ pink triangle used during AIDS activism from the mid-1980s. Both connect to (in)security, particularly how certain collectives/individuals are constituted as threatening, and how images and symbols are used to represent, to call attention to, insecurity.

The story of the pink triangle is actually a tale of two triangles: one triangle pointing up, the other down. This is an important distinction that marks two somewhat different, even if overlapping, political uses. The downwards pointing triangle, was used in Nazi Germany to mark (suspected) non-heterosexual bodies in concentration camps. In the 1970s, this triangle was appropriated by gay activists and became a symbol of the gay liberation movement in the USA. You can also find pink triangles around the world memorializing both the punishment and killing of homosexuals during WWII, and the AIDS crisis. The Silence = Death (upwards pointing) triangle emerged in the mid-1980s. It is a repurposed version used by the artivist collective Silence = Death—associated with AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power (ACT UP)—to call attention to AIDS-related issues.

Under Hitler many thousands of men were convicted of homosexuality. Those convicted were forced to wear pink triangles identifying their conviction for homosexuality, which was deemed unnatural and illegal at the time. The pink triangle functioned in the same way as the better-known yellow Star of David marking Jewish bodies. A quarter century after the end of WWII, in 1970s New York, this triangle started to be reclaimed and soon became a symbol of gay pride and was used to draw attention to the oppression of non-heterosexual individuals, how they were rendered insecure through high political and society-wide discourses constructing them as ‘abnormal’ and threatening.

An example of this discourse of queer threat and its consequences is the USA’s queer panic during the 1950s ‘Lavender Scare’ when gay men and lesbians were removed from state employment, deemed national security threats and possible communist sympathisers.

Refashioning the Nazi pink triangle, it was used in a celebratory fashion, a symbol for pride, solidarity and community, and the fight against homophobia. What makes this symbol so important is its origins. The political power of this symbol lies in the inability to extricate it from its history: without this politically charged history, the Pink Triangle would be nothing more than a randomly chosen emblem for the gay movement. Its visual link to the Nazi version is crucial to its political effect and power in reframing the security discourse.

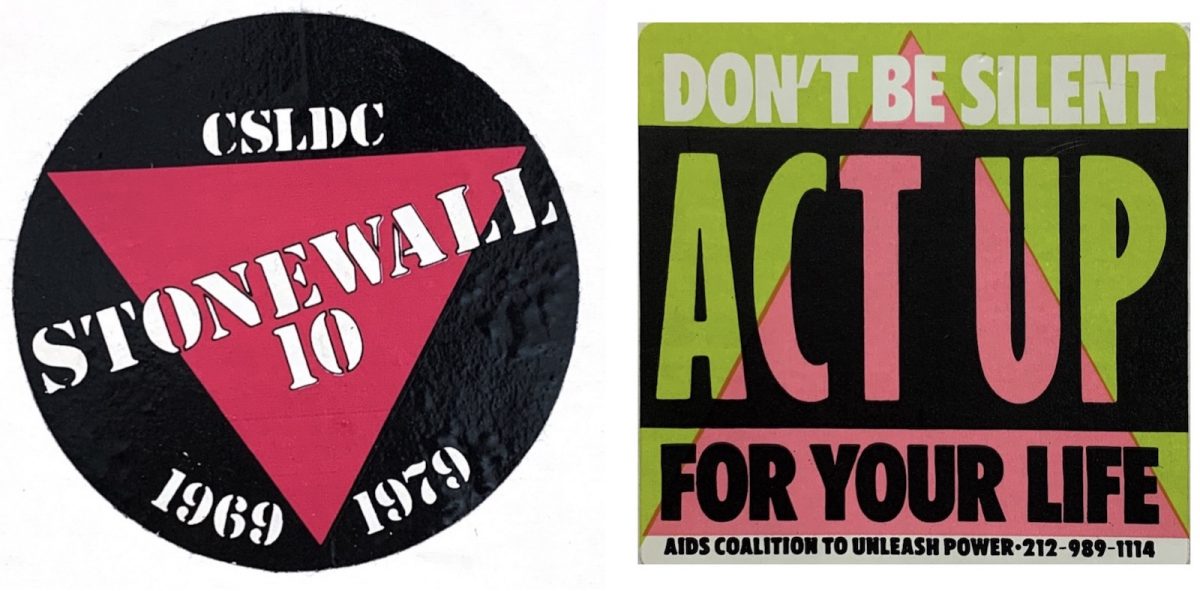

The optimism and hope of gay liberation in 1970s USA were accompanied by increased presence of this triangle. It was used similarly to how the rainbow flag is at contemporary Pride events: as a celebration at marches and as a way of making queer space. Then, in the 1980s, as the AIDS crisis gripped the USA, the upwards-pointing ‘Silence = Death’ triangle emerged. While the difference in point direction appears small, there is a different politics attached to each triangle: pride and celebration (figure 1) versus death and resistance (figure 2).

Figure 1 (L). CSLDC ‘Stonewall 10’ Sticker. Figure 2 (R). ACT UP ‘Don’t Be Silent’.

From the mid-1980s, there is rarely an occasion, a protest or march, when the ‘Silence = Death’ triangle visual is absent. It functioned as a call to mobilisation, effectively saying: if you don’t come out, if you don’t fight, if you stay silent, we will die and they (the government) will let us; silence is killing us. In terms of ‘into the streets’ demonstrations and material produced to resist homosexual demonisation and AIDS ignorance, the ‘Silence = Death’ triangle was visually hegemonic.

Unlike the reclaimed Nazi pink triangle, the ‘Silence = Death’ version was not an exclusively queer symbol and it invoked a politics of fear and anger rather than hope. ACT UP sought to tackle AIDS-related issues and stigmatisation. And while AIDS overwhelmingly affected the queer community—particularly men who had sex with men—ACT UP was not an LGBT organisation. It held intersectional values, which can be seen in the translation of its key messages into Spanish and the group’s focus on previously neglected groups such as women with AIDS.

ACT UP, like the British Suffragettes I have written about, paired theatricality and into-the-streets actions with coordinated visuals (the ‘Silence = Death’ triangle being most famous). Combining a unified visual aesthetic and direct action, ACT UP drew attention to oppressed people’s insecurities and reframed the debate on not just HIV/AIDS but gender and sexuality. They made those left to die by a deliberately inactive US government the referent objects of security. Both pink triangles are painful reminders that particular bodies, human lives, were targeted and left to die because of their (suspected) sexual practices and assumed monstrosity and danger to society.

Conclusion

It is fair to say that visual scholarship has made a veritable impact on IR. There is, however, still much to be done. So, I will keep my concluding remarks deliberately short because this piece should hopefully serve as a provocateur and empirical-theoretical inspiration. WJT Mitchell famously wrote that “all media are mixed media” (2005: 260). Supporting the visual approach, I’ve outlined above, Mitchell continued that: “the very notion of a medium and of mediation already entails some mixture of sensory, perceptual and semiotic elements”. In this sense, I want to make one important point that visual scholars might engage with moving forward: if texts anchor and give visuals meaning, then visuals can also be said to anchor and provide meaning to text. Seeing, combatting, and studying (in)security requires more than words.

[1] Swati Parashar and Jane Parpart (2018) recently published an important edited volume on ‘silence’, which is crucial in deepening our understandings of the way silence functions politically.

Bibliography

Andersen RS and Vuori JA. (2018) Visual Security Studies: Sights and Spectacles of Insecurity and War, London:Routledge.

Andersen RS, Vuori JA and Guillaume X. (2015) Chromatology of security: Introducing colours to visual security studies. Security Dialogue 46:1-18.

Baker C. (2020) ‘Couture military’ and a queer aesthetic curiosity: music video aesthetics, militarised fashion, and the embodied politics of stardom in Rihanna’s ‘Hard’. Politik 23:11-51.

Barthes R. (1977) Image, Music, Text, New York:Hill and Wang.

Berents H. (2019) Apprehending the “Telegenic Dead”: Considering Images of Dead Children in Global Politics. International Political Sociology 13:145–160.

Bleiker R. (2015) Pluralist Methods for Visual Global Politics. Millennium Journal of International Studies 43:872-890.

Bleiker R. (2019) Visual autoethnography and international security: Insights from the Korean DMZ. European Journal of International Security 4:274-299.

Bleiker R, Campbell D, Hutchison E, et al. (2013) The visual dehumanisation of refugees. Australian Journal of Political Science 48:398-416.

Bleiker R and Kay A. (2007) Representing HIV/AIDS in Africa: Pluralist Photography and Local Empowerment. International Studies Quarterly 51:139-163.

Callahan W. (2015) The Visual Turn in IR: Documentary Filmmaking as a Critical Method. Millennium 43:891-910.

Cooper-Cunningham D. (2017) Analysing but Not Seeing: What’s Missing When We Forget Images in IR. E-International Relations.

Cooper-Cunningham D. (2019a) Review of Seeing Politics: Film Visual Method and International Relations (Sophie Harman). E-International Relations.

Cooper-Cunningham D. (2019b) Seeing (In)Security, Gender and Silencing: Posters in and about the British Women’s Suffrage Movement. International Feminist Journal of Politics 21:383-408.

Cooper-Cunningham D. (2019d) Showing, Speaking, Doing: How ‘Seeing Politics’ Forces Us to Rethink Epistemological and Methodological Biases in International Relations. The Disorder of Things.

Cooper-Cunningham D. (2020) Drawing Fear of Difference: Race, Gender, and National Identity in Ms. Marvel Comics. Millennium: Journal of International Studies 48:165-197.

Duncombe C. (2019) The Politics of Twitter: Emotions and the Power of Social Media. International Political Sociology 13:409-429.

Duncombe C. (2020) Social media and the visibility of horrific violence. International Affairs 96:609-629.

Fierke KM. (2013) Political Self-sacrifice: Agency, Body and Emotion in International Relations, Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

Friis SM. (2018) Virtual Violence: Militant Imagery, Online Communication, and the Islamic State. University of Copenhagen.

Guillaume X, Andersen RS and Vuori JA. (2016) Paint it black: Colours and the social meaning of the battlefield. European Journal of International Relations 22:49-71.

Hansen L. (2000) The Little Mermaid’s Silent Security Dilemma and the Absence of Gender in the Copenhagen School. Millennium Journal of International Studies 29:285-306.

Hansen L. (2011) Theorizing the Image for Security Studies: Visual Securitization and the Muhammad Cartoon Crisis. European Journal of International Relations 17:51-74.

Hansen L. (2017) Reading comics for the field of International Relations: Theory, method and the Bosnian War. European Journal of International Relations 3:581-608.

Harman S. (2019) Seeing Politics: Film, Visual Method, and International Relations, Qeuebec:McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Heck A and Schlag G. (2013) Securitizing Images: The Female Body and the War in Afghanistan. European Journal of International Relations 19:891-913.

Lisle D and Johnson H. (2019) Lost in the aftermath. Security Dialogue 50:20-39.

MacKenzie M. (2020) Why do soldiers swap illicit pictures? How a visual discourse analysis illuminates military band of brother culture. Security Dialogue.

Malmvig H. (2020) Soundscapes of war: the audio-visual performance of war by Shi’a militias in Iraq and Syria. International Affairs 96:649-666.

Parashar, Swati, and Jane Parpart, eds. 2018. Reconsidering Gender, Silence and Agency in Contested Terrains. London:Routledge.

Särmä S. (2018) Collaging Iranian Missiles: Digital Security Spectacles and Visual Online Parodies. In: Vuori JA and Andersen RS (eds) Visual Security Studies: Sights and Spectacles of Insecurity and War. London:Routledge,114-130.

Weber C. (2011) I am an American: filming the fear of difference, Bristol:Intellect.

Williams M. (2018) International Relations in the Age of Images. International Studies Quarterly 62:880-891.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- World Security in the 21st Century: Re-evaluating Booth’s Approach to Critical Security Studies

- Critical Security Studies Needs to Better Consider the Intricacies of Social Media

- What I Learned from Geolocating 1,000 Satellite Images

- Sensible Politics: Expanding from Visual IR to Multisensory Politics

- The Importance of Racial Inclusion in Security Studies

- What Might a Global Security Studies Look Like?