By sheltering in place and working from home during the COVID-19 lockdowns, consumers have stressed broadband networks to the breaking point. On the world stage, disparate reactions by China and the US to the demand for remote communication and entertainment mark a new inflection point in the contest for global 5G leadership. Yet the significance of this moment is lost in the daily welter of news about the pandemic. While the US Congress flirts with an infrastructure bill and passes light-touch 5G framework legislation, China has ordered major economic stimulus in the form of new infrastructure investments, including 5G, for as much as $394b. US carriers consider incremental steps to accelerate network rollouts – meanwhile, in the space of one week, China’s 5G industry protagonists awarded $5b of new contracts and posted strong financial results in the face of the stiffest of economic headwinds.

Here’s a scorecard for the pandemic era, comparing the US and China in four key areas of contention: policy, standards, deployments, and international contracts. Spectators will observe the ever-widening distance between the contestants.

Policy

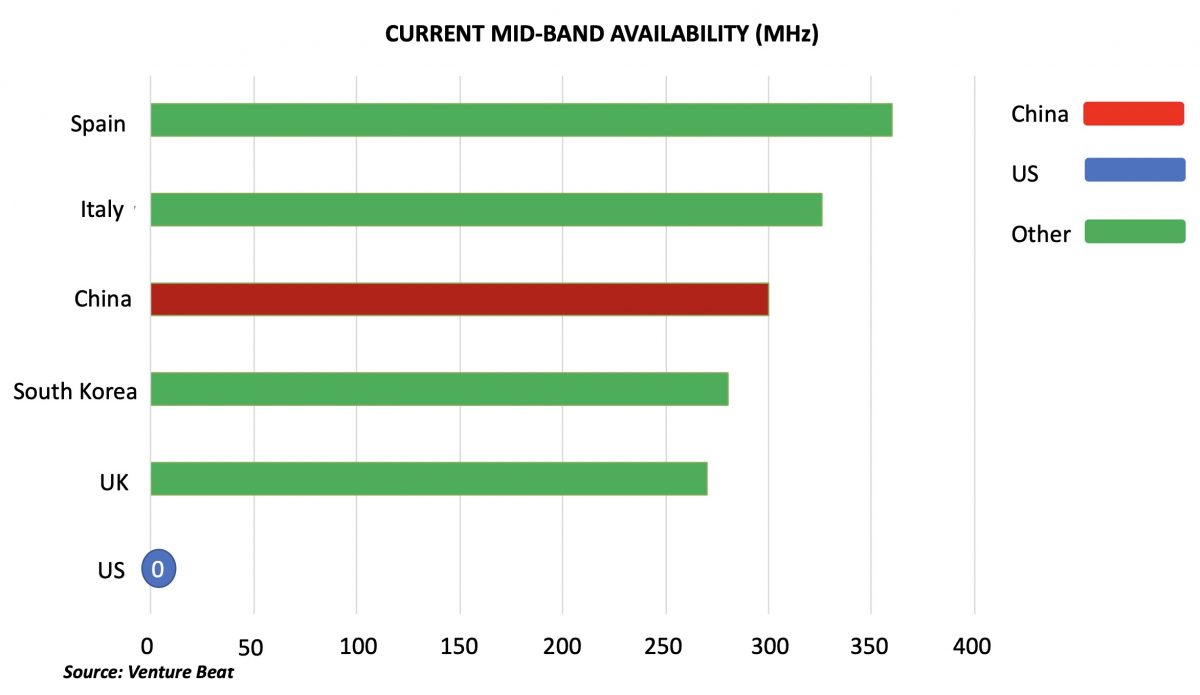

China’s state command-and-control model set the stage for the swift domestic implementation of 5G well prior to the COVID-19 crisis. Authorities moved decisively to allocate mid-band (or “Goldilocks”) spectrum that optimally balances coverage with performance. The state also provided land grants to carriers on favorable terms in areas where they can quickly deploy the dense array of small cell antennas that 5G requires.

Meanwhile, US domestic policy has remained rudderless – even as the Trump administration has hyped the race for 5G. The Federal Communication Commission’s preference for market-based solutions has left key issues like cybersecurity standards to the industry to sort out for itself. The FCC’s red-tape slashing initiatives (e.g. fast-tracking zoning rights for antennae placement) have devolved into lawsuits that now languish.

A particularly thorny matter remains the allocation of mid-band Goldilocks spectrum, currently in the hands of government and private operators. Existing commercial arrangements and possible signal interference will delay 5G roll-out in that efficient slice of spectrum. Instead, the US is placing high-band millimeter wave spectrum front and center in its 5G strategy. While millimeter wave offers faster speeds, the signals are only effective over a few hundred feet, are easily blocked by physical objects, and require more costly on-the-ground infrastructure.

Standards

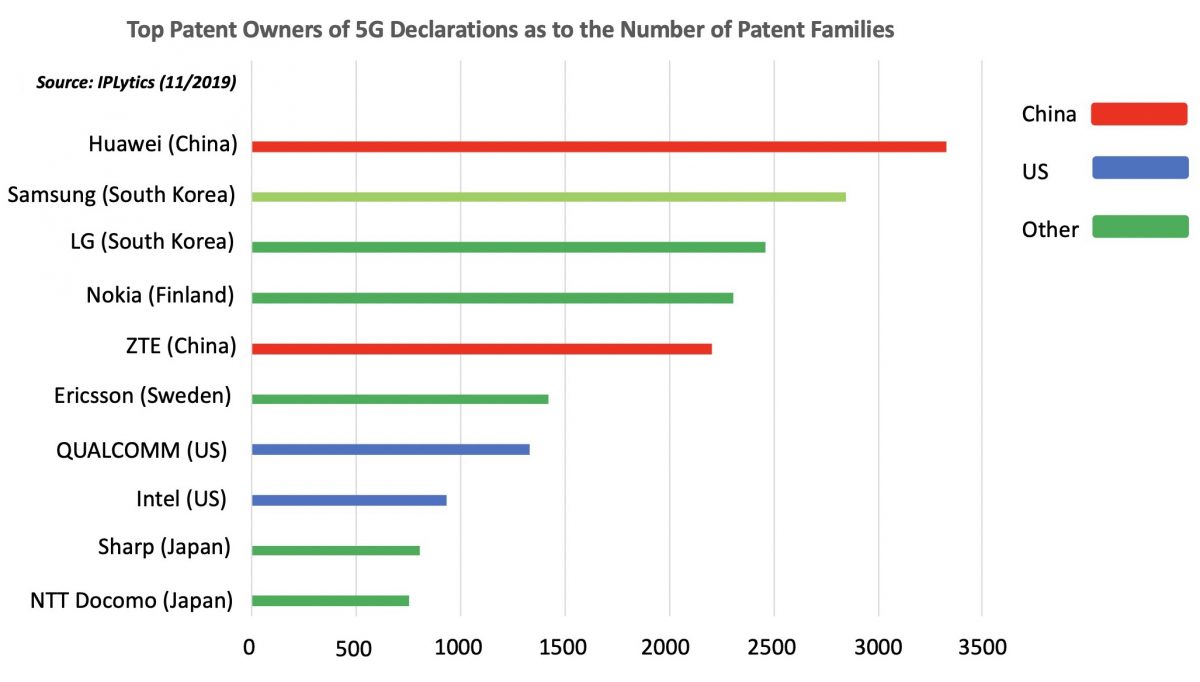

If 5G is a race, whoever set the rules of the road has the inside track. The underlying intellectual property of the technology defines its development framework, creates dependence for other developers, and establishes future revenue streams from licensing royalties for patent holders. In the contest to develop standards-setting IP (so-called “standards essential patents,” or SEPs) China maintains a significant quantitative lead.

Chinese companies accounted for 34% of SEPs granted as of last year. In comparison, the US had a mere 14%, trailing both China and South Korea. Huawei alone boasts 15% of all SEPs, having committed massive state-subsidized budgets to this strategic R&D exercise. Chinese companies have likewise outflanked their US counterparts in their presence at the many global industry gatherings devoted to establishing 5G standards.

Domestic Deployments

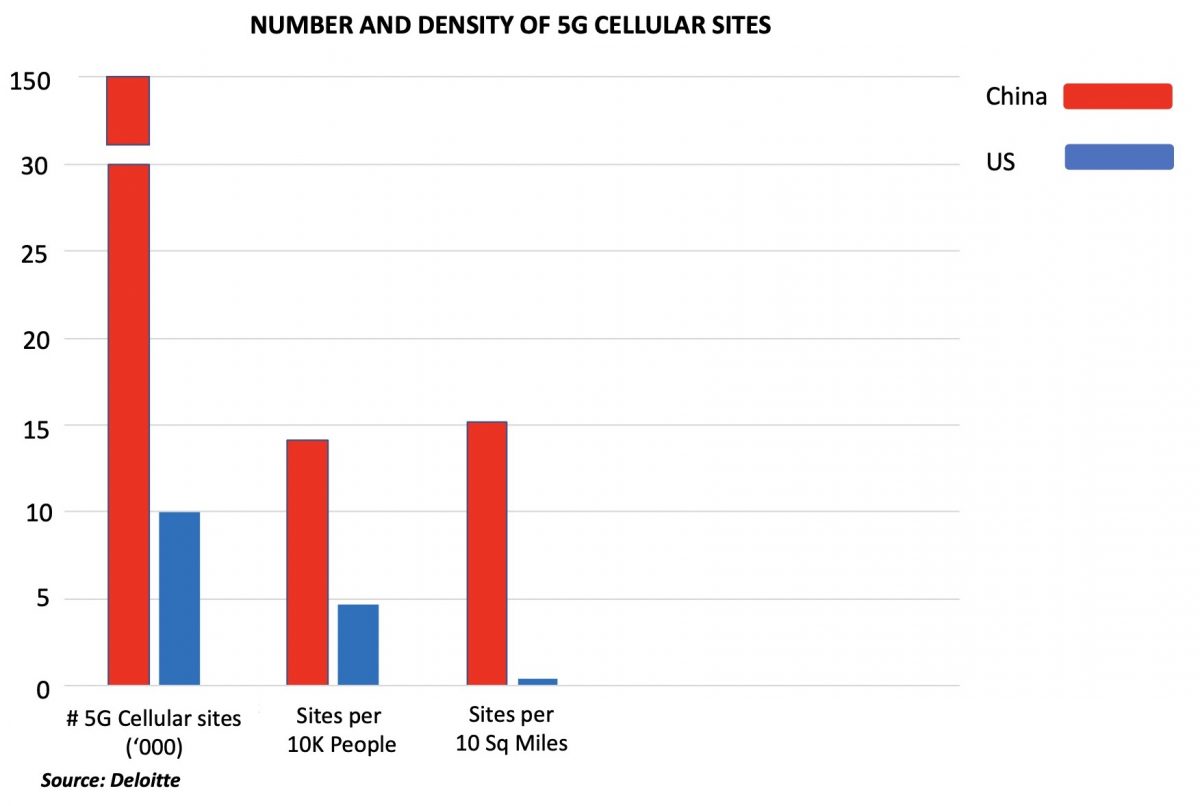

The ultimate test of success is actual domestic deployments, and thanks to a national investment of $411b on 5G mobile networks – topped up by the additional tens of billions committed during COVID-19 – China expects full national coverage by the end of 2020. A view of the number and density of cellular sites by country tells the story:

According to ABI Research, Chinese operators will have 143 million 5G subscribers by the end of 2020, “an overwhelming 70% of the total worldwide connections, compared to about 28 million in the US by 2025.” In particular, China Mobile, the world’s largest carrier by subscribers, has pulled out all stops for 5G deployment, demonstrating working applications for advanced technologies like telesurgery and augmented reality. China Mobile’s $5.2b worth of new 5G contracts signed with vendors in April cements its position as undisputed leader.

Though US carriers have clear 5G strategies, they have thus far largely fudged their rollouts through misleading consumer marketing campaigns. Sprint claims to cover 11 million people with its 5G network in five cities, but doesn’t reach Gigabit speeds. AT&T got caught deploying a 5G icon to mobile phones while still running the devices on its current 4G networks. Among US carriers, Verizon offers the fastest network and the most enabled devices, but coverage is limited within its 5G markets.

International Contracts

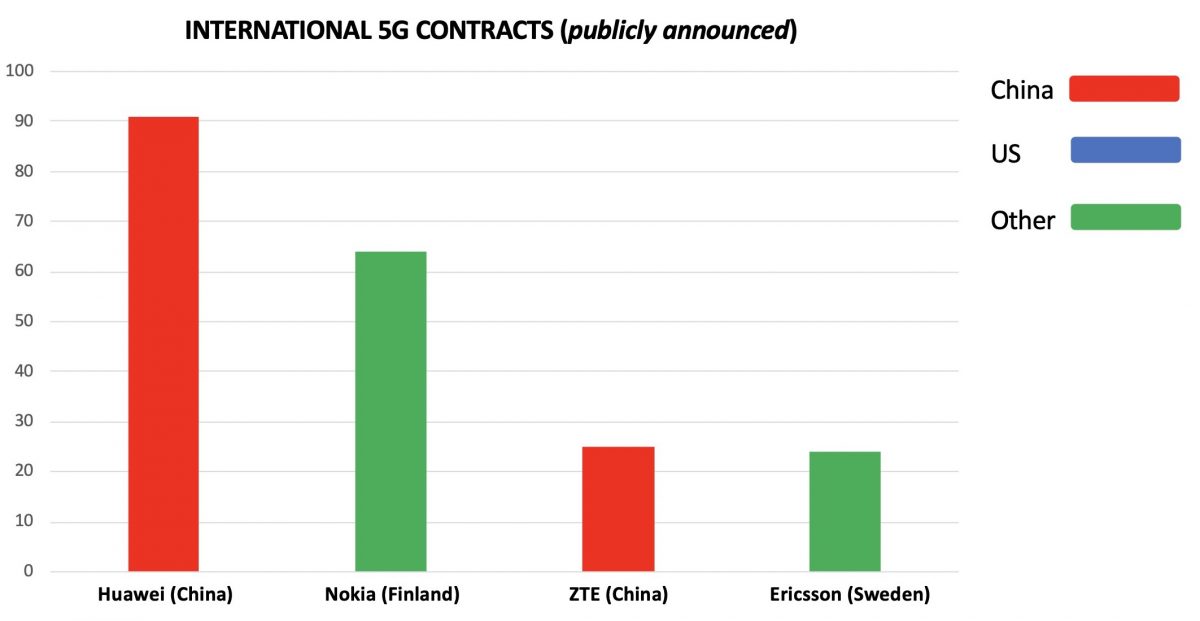

The Trump administration’s PR campaign has successfully portrayed China’s tech companies as high risk vendors, using genuine security concerns to stoke the trade war. And yet Huawei can still claim that two-thirds of all 5G networks outside of China use its gear.

The PRC’s export-led telecom achievements are indisputable. Huawei currently has 800 international projects currently active, while ZTE and China Telecom have over 200 each (not, of course, all 5G-related). However, their collective go-to-market strategy has been to compete on price, leading to a higher concentration of clients in the developing world (with attendant financial risk).

US government prohibitions have effectively closed some doors to Huawei and ZTE. Australia, Japan, New Zealand and Taiwan have banned Huawei from their networks. Yet, 54 other nations plan to work with the company, including US allies Spain and the UK.

Beyond COVID

National leadership goes beyond any one company’s ability to stand up an end-to-end 5G network using only its own equipment – Huawei’s particular distinction. Internationally, China dominates in network hardware sales. However, crystal ball gazers point out that the US industry is positioned to lead a transition from hardware-based to software-defined 5G networks. That could be transformational in supplanting the dominance of legacy hardware manufacturers like Huawei. But without bold support and big checks from the US federal government, private sector firms lack the wherewithal to seize that opportunity during COVID economic uncertainty.

The US-China Trade War exposed how inextricably linked the two countries are in the technology sector generally and the 5G supply chain in particular. Among US companies on the S&P with 20% or more revenue exposure to Greater China, all but five are tech companies. And all are of those in the business of 5G. In some of China’s technology sectors – notably integrated circuits crucial to 5G – imports outweigh local production by up to a factor of five. Likewise, more than a third of Huawei’s core suppliers are US companies. Both nations’ equipment manufacturers in turn rely on companies like Ericsson, Nokia, Samsung, and a range of sources from other countries for components. Within the 5G ecosystem competitors have no choice but to collaborate.

And yet the COVID-19 crisis has pushed competitors further apart. Of the $5.2b worth of contracts awarded this month by China Mobile 57% went to Huawei, 29% to ZTE, 12% to Ericsson, and the balance to other Chinese companies. Evidence, if any were needed, of the PRC’s China-first agenda and heightened efforts to scrub foreign vendors from its domestic networks. Another threat to globalized 5G ecosystem is the strain on the supply chains for critical network gear caused by the pandemic, as chip manufacturers pull back production and idle plants. And, of course, COVID-19 restrictions on public activities limit workers’ ability to build out network infrastructure.

The Chinese government has acted aggressively on the maxim “never waste a good crisis.” Meanwhile, the US’ crisis response has consisted of doubling down on security concerns about China’s tech vendors. Those concerns are real. However, public policy that relies on pitting US competitors against their Chinese counterparts misses the point – which is to hasten the proliferation of 5G. It also serves to bifurcate the market for next-gen wireless communications, posing both technical and geopolitical risks. A lack of unified standards would fail to guarantee network interoperability and performance. That has implications for everything from consumer and commercial applications to defense partnerships: smart phones that can’t communicate across borders; networked industrial devices marooned on incompatible Internets of Things; reconnaissance and surveillance applications unable to transfer data efficiently. Such a scenario undermines short-term economic recovery as well as the long-term upside of 5G. If the US wants to reclaim the lead in this race, it needs to act like a leader.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Lessons America’s Adversaries Can Learn from the Covid-19 Pandemic

- Opinion – Nationalism and Trump’s Response to Covid-19

- Doom, Boom or Hibernation? Covid-19 and the Defense Industry

- Opinion – Cambodia’s COVID-19 Success, Economic Fallout and Image Crisis

- Opinion – COVID-19 and the Coming Crisis in America

- Opinion – Omicron and Navigating the New Normal with Covid-19