It is difficult to overstate the impact of Brexit European defence policy – from here onwards referred by the acronym CSDP, the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy. Indeed, the departure of one of the European Union’s (EU) “Big Three” – to include France and Germany – would always lead to a long term shift in the geopolitical profile of the EU that is still difficult to fully appreciate. Nonetheless, the departure of the United Kingdom (UK), which remains, with France, one of two military powers in Western Europe with nuclear weapons and deployment capabilities outside of Europe (Keohane, 2018) was not necessarily a negative one for the CSDP. However traumatic Brexit has been for the EU, this event also meant the exit of the most reluctant EU member to an autonomous European defence policy outside of NATO.

As last year’s Munich Security Report (2019, p.24) recognized, the ‘deepening of CSDP was something that London was notoriously reluctant to.’ Already in the year of UK’s referendum to leave the EU, Zandee (2016) has stated that ‘the British vote (…) can open the door to a real strengthening of the CSDP (…) without the blocking position of London.’ In this article, I shall take stock of this prediction and whether or not “real strengthening” has been happening since the UK’s momentous vote.

Germany: The indispensible EU member

When it comes to the evolution of the political direction of the EU, and in particular the CSDP, one country remains the most influential: Germany. The biggest economy in the EU was almost unanimously considered as the most influential and powerful member state of the EU during the last decade, independently from the source, be it from academic experts, European and global media outlets and senior officials of the EU and other countries (such as Kundnani 2015; Matthijs, 2016; Paterson, 2011; Schweiger, 2014; Stelzenmüller, 2016; The Economist, 2013). Such a leadership, or even according to some, ‘Hegemony’ (Bulmer and Paterson, 2016; Kunz, 2015), which remains a rather charged concept in the realm of International Relations, will not be the focus of this article. Nonetheless, suffice to say that Germany remains the essential EU country without which, for political, economic, and even strategic reasons no major reforms in the CSDP can advance (Major and Mölling, 2018).

The past ten years, following the Euro crisis of 2009-onwards, was the moment when Germany stood out as the indispensible member of the EU. The crisis provided an opportunity for Germany to assert a clear leadership in defining the EU’s policies. This is a trend with would go on in further crises, such as the one following the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 (Daehnhardt, 2015) or the refugee crisis with its height in 2015 (Meiritz, 2015). Even though it had already been an important state in the EU, for instance, in defining the rules for the Economic and Monetary Union in the 1990s (Baun, 1996), Germany exercised its power in the EU in the context of the Franco-German axis – even serving as a junior partner to the French in matters of foreign and security policy (Pachta, 2003).

When it comes to the European defence policy, the turning point for Germany, in hindsight, came in 2014 after the Crimean crisis (Pond, 2015). When Russia invaded another European country it came as a shock to the German establishment (Kwiatkowska-Drożdż and Popławski 2014) – a country traditionally keen on maintaining as close a relationship as possible with Russia for historical and economic reasons (Götz, 2007). However, those strong ties were not enough do deter Berlin from taking a lead role in applying crippling sanctions on the Russian economy (Daehnhardt, 2015; Pond, 2015). Additionally, in the Munich Security Conference of 2014, there were three major speeches delivered by members of the German government on defence policy, notably by its president (Bundespräsidialamt, 2014). These were followed, in 2015, by a statement from the Defence Minister Von Der Leyen that introduced the concept of ‘leadership from the middle’ [of the EU]. The 2016 ‘White Paper on German Security Policy and the Future of the Bundeswehr’ put to paper those and other speeches by German senior officials and mentioned some of the concepts advanced for the future of German security strategies in previous years.

In the years between the Treaty of Lisbon becoming effective (December 2009) and the Brexit referendum, Germany continued its traditional policy of focusing mainly on NATO as the main field of cooperation in the area of defence (Kunz, 2018; Algieri, Bauer and Brummer, 2006). The successive Merkel governments were not interested and/or willing in investing more in European defence and in deepening the capabilities of CSDP – not even on the military capabilities of the German army, which suffered years of investment shortfalls. An official report by the Military Commissioner of the German parliament, cited by Deutsche Welle (2018), stated that less than 50% of the main weapons systems of the German armed forces were ready for interventions, or even for training, of the country’s military forces.

More importantly, as the abstention in the 2011 Libya operation had shown, Germany’s aversion to the use of military force remained an important factor (Brockmeier, 2013). The lack of German leadership at a time when German economic, and even political preponderance, in the EU was unrivalled by any other state meant that a truly integrated European defence had hardly come any closer to being materialized by the wake of the Brexit vote than when the CSDP was originally created in 1999. As Anand Menon considered in 2010 (p.88), ‘most Member States share an increasing disillusionment with the CSDP.’

Main German interests and preferences for the CSDP

Any analysis of Germany’s role in forming the EU’s security and defence policy in the wake of Brexit shall begin by establishing the main German interests and preferences for European defence policy – for which the main source will be the German Government itself and namely, the aforementioned most recent “White Paper on Security Policy and the Future of the Bundeswehr,” which is the key German policy document on security policy.

The first priority for Germany concerns the importance of preserving the sovereignty of the entire European continent, by which the country clearly identifies its own security with the security of all its neighbours and fellow EU members. The second priority is the commitment to the further integration of European defence policies. For this regard, Germany’s 2016 White Paper: ‘strives to achieve the long-term goal of a European Defence and Security Union’ that includes ‘strengthening the European Defence industry’ and ‘integration of military and civilian capabilities.’ From this second quote, we can deduce a nuance that is important in understanding some of the differences arising with Paris over the future development of the CSDP.

Reading between the lines of the White Paper, it seems clear that maintaining unity and cohesion between the entire EU and in cooperation with NATO are the German priorities, even if that entails compromises in the EU that lead to less ambitious initiatives under the CSDP (Algieri, Bauer and Brummer; 2006; Von der Leyen, 2019). On the other hand, France gives absolute priority to augment integrated European military capabilities – its own 2017 Strategic Review document (commissioned after the election of Emmanuel Macron) referring to the need to ‘respond’ effectively to the US request to ‘share the burden’ of military expenditures.

The third priority comes attached to the second: Germany supports a deepening of the CSDP, but not (unlike France, for instance) at the expense of a weakening of its commitment to the NATO alliance, which includes a component of military presence of American troops on German soil (Algieri, Bauer and Brummer; 2006). This is a position that German governments have consistently defended, even under the rather strained bilateral relationship with Washington under President Trump (Erlanger, 2019). In the 2016 White Paper, Germany declares that among its national interests ‘is the strengthening of transatlantic and European security partnerships.’ Thus, for Berlin, maintaining full compatibility with NATO remains the bedrock of its defense policy, arguably trumping (no pun intended) its commitment to the CSDP, at least until now.

Finally, a very important principle for Germany as a normative power, is the defense of what it considers as indispensable values connected to its belonging to the European Union and, in a broader way, the Western world. In the realm of security policy, Germany states in the White Paper its perennial upholding of multilateralist principles, reiterating multiple times its strict respect for multilateral norms. In practice, it states that it should intervene militarily with an international mandate (namely from the UN), helping to put its refusal to intervene in Libya in 2011 in the context of a consistent national policy.

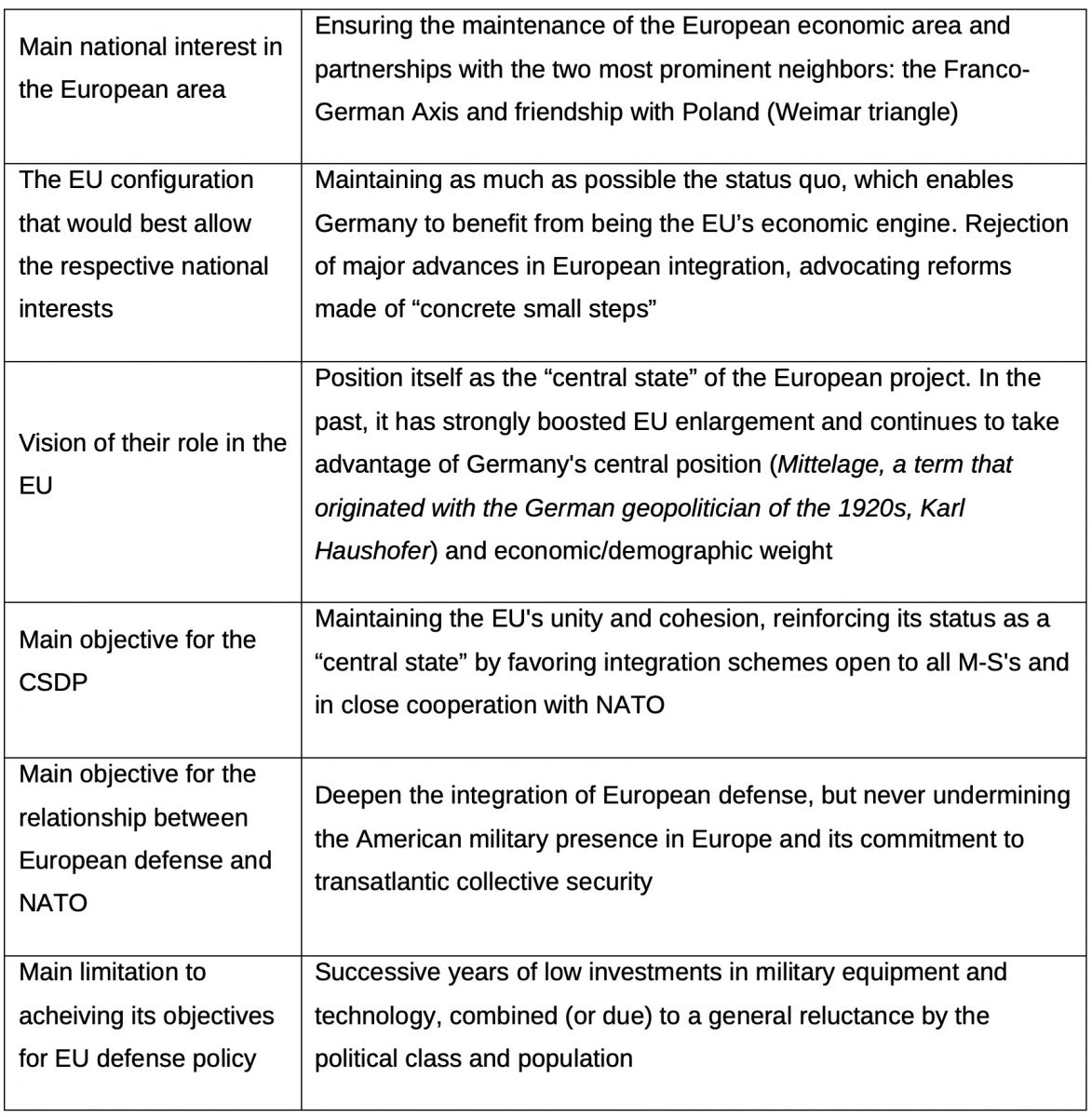

Any self-respecting analysis must go beyond the written words and dive into what is their meaning in an overall strategic sense for Germany’s policy. As such, I believe that one can identify certain principles which guide Germany in the EU. These are summarized in the table below and will help guide the next stage of this analysis – what policies were actually implemented in the European Defence policy after Brexit and the German influence on those.

Germany and the EU: The main guiding principles (own work)

PESCO: The landmark for a new beginning in the German-shaped CSDP

If one looks back, almost every progress in the European Integration begins with new institutional arrangements, and the post-Brexit renewed push on Defence policy was no exception. In 2003, the EU had published its first European Security Strategy Strategic document as a Union (essentially its own White Papers), and this was replaced in 2016 by a new document written under the authority of then High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Federica Mogherini. Even though it is nominally written under the authority of the Commission, this is a policy area where member-states have been reluctant to delegate too much power to Brussels, and the new document necessarily reflects a compromise among all the member-states. The 2016 Global Strategy reflects an intention to bring renewed life to the CSDP, being ‘doubly global, in geographic and thematic terms’ (Zandee, 2016). Several initiatives have been implemented since the Strategy was approved:

- Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO; 2017)

- European Defence Fund (2017)

- Military Planning and Conduct Capacity (2017), which is part of the Military Corps of the External Action Service and constitutes the EU’s first permanent operational headquarters, a long-standing Franco-German ambition.

- Coordinated Annual Defence Review (2019)

In the Global Strategy, the EU undertakes to achieve ‘strategic autonomy.’ In addition, there is a ‘principle-based pragmatism’ that guides the implementation of the strategy, but again without defining it in detail. In an assessment of this Global Strategy, Bendiek (2016) was critical of the ambiguity of ‘defence cooperation’ proposed for the CSDP ‘without a convincing description of how this great ambition should be achieved under resource scarcity conditions, strategic discord among member states and continued adherence to the consensus commitment in decision making,’ (the consensus rule having been, in my view, a frequent block in more ambitious proposals for the CSDP).

The document seeks to balance such ‘strategic autonomy’ with the reiteration of the importance of NATO for the defence of Europe, in a commitment to a majority of ‘Atlanticist’ or strongly pro-NATO member states. In this way, the document refers to the objective of deepening the transatlantic bond and further ensures that NATO remains ‘the primary framework for the majority of Member States, whose defensive planning and development of military capabilities are conducted in full coherence with NATO’s defence planning process’ (European Commission, 2016).

So, this new push in the CSDP is not (yet) ‘Europe taking its fate its own hands,’ as Merkel famously declared it must do in 2017 (in Paravicini, 2017) after the first round of G7 and NATO meeting with US president Donald Trump. Nevertheless, PESCO can indeed be the bedrock foundation for the future of European defence policy, and it was likely the biggest institutional change for the CSDP since its creation at the turn of the century.

PESCO was a mechanism made possible under the concept of Enhanced Cooperation (in which a minimum of 9 member states decide to reinforce cooperation or harmonization in a given area), introduced by the Treaty of Lisbon. In Defence, PESCO was created with support from the German government (Major and Mölling, 2018) and institutionalized in 2017. In September 2017, an agreement was made between EU foreign ministers to move forward with PESCO with 10 initial projects. The agreement was signed on November 13 by 23 of the 28 member states. Ireland and Portugal notified the High Representative and the Council of the European Union of their willingness to join PESCO on 7 December 2017, and PESCO was activated by 25 states on 11 December 2017 with the approval of a Council decision (European Council, 2017). Denmark and Malta did not participate, the first being consistent with its position to not participate in the CSDP (Cunningham, 2018). The biggest absentee from PESCO was, of course, the UK, which finally left the EU in 2020.

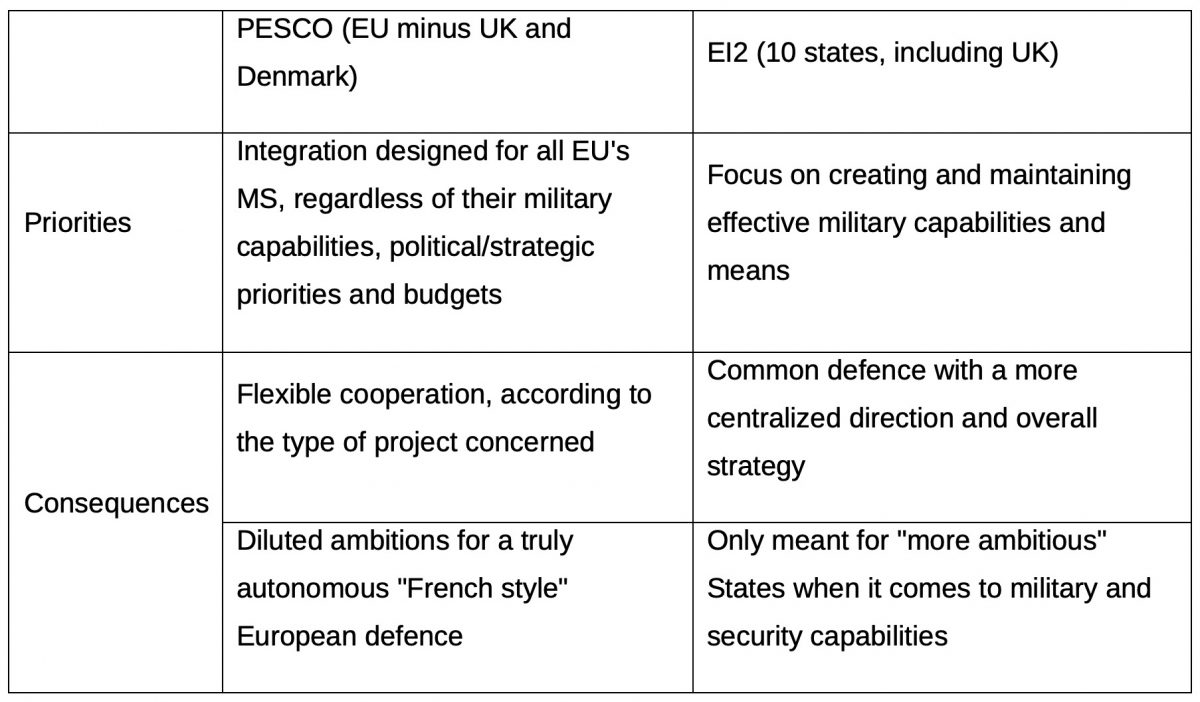

The description by Major and Mölling (2018) seems to support the view that PESCO has an initiative primarily aimed at combining a will to further EU defence policy, while not hurting internal cohesion; ‘because of German lobbying, PESCO has become an inclusive political effort (and bureaucratic due to) typical EU procedures and institutions that allowed the participation of all EU states, rather than an exercise focused on (building) capabilities’ at the security/military level. According to the same authors, ‘France preferred the opposite: an exclusive club for states that are really capable and willing to contribute forces to operations.’ Major and Mölling add that, ‘Disappointed with a Germanized PESCO, Paris is now shaping its European Intervention Initiative (EI2) outside the EU,’ allowing for the inclusion of the UK, which remains as previously mentioned the other largest military power in Western Europe.

France: Indispensible partner, but regular source of disagreement

This is the time to address one of the elephants in the room when it comes to European Defence: even if Germany remains the indispensable EU member, nothing can be done without France’s approval – especially not in the matters of defence and security, for which France is arguably still a more capable country than Germany and certainly a less inhibited one for well-known historical reasons. Germany’s pacifism was a feature of Cold War times and one that remains until the present day (Bittner, 2019). In 1971, Chancellor Willy Brandt summed up this paradigm in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize: ‘War is not the ultima ratio but the ultima irratio.’

Since the Brexit vote, France has gone through its own significant political election. In 2017, under the more real threat than ever of the election of the highly Eurosceptic Marine le Pen, Emmanuel Macron was elected President of France with the most pro-Europeanist mandate ever in the Fifth French Republic (The Economist, 2017). In his plan for the “revival” of the EU, strengthening the CSDP was one of the priorities, with Macron also referring to the goal of creating a ‘European army’, a statement soon echoed by Chancellor Merkel (Brunsden and Chazan, 2018).

Was this a revival of the Franco-German Axis in the realm of defence policy? Perhaps, but the interests of the two states regarding the future of EU Defence remain divergent. In July 2017, the two countries agreed at a bilateral meeting (Koenig and Walter-Franke, 2017) on an ambitious agenda for capabilities in the context of the military operations in Sahel, where France had long been doing the heavy lifting. This was a step in the right direction for European Defence after years of disagreements over military interventions outside Europe and with Paris reportedly becoming increasingly frustrated by Germany (Munich Security Report, 2019). Cooperation in the Sahel, on paper, should be the perfect combination of the French (military) and German (civil) forces. Nonetheless, a more profound political divide remains between Paris and Berlin, now a matter of an occasional cooperation agreement. Indeed, a close examination of the French and German approaches to defence and security, even after the post-2016 push, reveals that structural differences have not disappeared, particularly with regard to the three dimensions of the current debate on security in Europe, as defined by Kunz (2018),

the East vs. South dimension; the definition of the right level of ambition for the CSDP; the question of whether Europe needs a Plan B for its defence in times of an increasingly weakened transatlantic link.

The 2019 Munich Security Report also refers to Franco-German differences:

Contrasting models of European defence cooperation also illustrate different mindsets: for the French, the integration of European defence is a means of strengthening their military power, strengthening military power is the means and improving European integration is the end (p.20).

These differences are all the more crucial as they also represent a deeper divide in the geographical security priorities between eastern and southern members or, respectively, the ones more worried and threatened by Russia and the countries traditionally more friendly to Moscow and more concerned with the security issues of the wider Mediterranean basin, like terrorism or even the refugee crisis, depending on the government.

Perhaps the most fundamental of these differences is the sense of urgency felt in Paris and Berlin when it comes to defence. In both countries, the idea that Europe’s strategic environment is deteriorating is today almost unanimous among official documents (Bundesministerium der Verteidigung, 2016; Ministère des Armées, 2017) and leading politicians (Gauck, 2014). But the money both governments allocate tells a clear story: The respective defence budgets are clear: France, after years of weak economic growth, still makes an effort to reach the 2% target (Chassany, 2018). Germany, which for the past decade benefited from an unprecedented budget surplus, only plans to reach 1.5% of GDP by 2024, and even this might be at danger (Sprenger, 2019) despite huge deficiencies in the Bundeswehr’s staff and equipment (von Krause, 2018). In particular, German Social Democrats are critical of increasing defence spending, warning of what they see as an ‘armament spiral’ (Agence France Press, 2017).

Summing up, since Macron’s election, France and Germany have repeated proposals to create a ‘European army,’ (Brunsden and Chazan, 2018) but different ideas still persist about what this – and the concept of ‘more Europe’ in general – would mean in practice. As such,

Paris still does not have the partner she hoped for (in Berlin) and is getting increasingly disappointed seems increasingly frustrated with the distance between Berlin’s words and actions (Munich Security Report, 2019, p.20).

Unlike Germany, France saw the need to develop multilateral cooperation with the most ambitious European countries in terms of military capabilities and the political will to intervene militarily when necessary – in their likeness. This cooperation was proposed in a “bottom-up” scheme and was introduced as the ‘European Intervention Initiative (EI2).’ According to the document (Bundesministerium der Verteidigung, 2018) that announced its launch, EI2 is ‘a meeting of European nations willing and able to promote their military interoperability and capability to conduct interventions’ (Ministère des Armées, 2018) and is part of France’s perennial effort to improve Europe’s strategic autonomy. According to Pannier (2018), ‘the project derives from a double assessment: that Europe urgently needs to improve its coordination in international crises and the interoperability of its forces’ and, in addition, that the countries most likely to mobilize forces alongside France ‘may or may not be members of the CSDP,’ a likely reference to the UK.

France’s expansive view on EU defence policy may cause renewed problems on the Franco-German axis. Germany is currently a member of EI2, but Berlin fears that the project will create conflict or redundancy with the European Union’s own initiatives to deepen military cooperation, especially the aforementioned Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO). Germany is also concerned about the participation of a future non-EU country, the United Kingdom, and the fact that only a third of EU member states are currently members, as Berlin would prefer a broader consensus at the bloc level (Koenig, 2018). Finally, Germany fears that EI2 might force it to become more active in military operations abroad, which is always a controversial issue for the country (Sanders IV, 2018).

EI2 was ambitious from the outset with regard to building European defence capabilities and appears to resemble an embryo of a “European Army.” According to an article on Stratfor (2018, p.2), ‘Paris fears that PESCO, which involves most EU countries, is too bureaucratic and too modest compared to EI2.’ Predictably, the solution found in the EU was a Franco-German compromise that postpones the fundamental decisions until afterwards, by including the EI2 concept within the overall PESCO structure. Following is my own summary of the various differences between the two conceptions:

Conclusions and questions for the future of EU defence policy

The answer to the question that names this article is mostly no, and a true European army remains distant. The ambitious speeches by Chancellor Merkel or even President Macron seem to be premature: the recent rhetoric of creating a European army still lacks the means, structures and institutions that can put it into practice, a situation that is unlikely to change anytime soon. Nevertheless, some of the most recent signs of progress, post-Brexit, appear to go in the direction of a greater importance for the CSDP.

When it comes to what can be foreseen for the short and medium term of European Defence and the German role in it, some conclusions can be drawn, and the EU and Germany (in cooperation with France and other EU members), have two main decisions to take regarding the future.

One: Regarding their ambitions

‘Today’s European governments face a decision similar to the one that the United States faced in the 1940s: increase their strategic means to meet their collective foreign policy goals or reduce their ambitions to adapt them their limited capabilities’ (Krotz and Maher, 2011, p.573). I consider it unlikely and frankly counterproductive that the EU will be able to avoid this issue indefinitely. The EU, in particular Germany, will have to accept that an increasingly important role at a global level potentially entails painful costs and risks, and has to determine which ones can be tolerable and unacceptable. One of the most positive developments in CSDP is that it finally begins to be debated what the European strategy should be, instead of considering only 27 national strategies. The fact that some of the ambitions set out in the 2016 Global Strategy were translated into concrete initiatives in the following years was a much needed progress.

Obstacles to progress remain ahead; in the harsh assessment of Adrian Hyde-Price, ‘despite the progress made in institutionalizing the CSDP, the military effectiveness and operational performance of EU missions has been disappointingly poor; these missions are almost always small-scale humanitarian aid, operations training and the rule of law in a largely benign and consensual environment. […] The military production of the CSDP was, therefore, very low.’ This even leads Hyde-Price to ask if the growing number of debates around the European defence are not ‘too much noise for nothing’ (2018, p 400).

Two: Regarding the relationship to be established in the future between the EU’s defence and NATO

At the end of the same year as the Brexit referendum, Donald Trump was elected President of the USA. Traditionally, American leadership within NATO reflected a trade-off between security and autonomy, which has led Washington to accept covering most military costs and resources in exchange for being able to guide general policy within the transatlantic alliance. That might be changing in the future, and one should not forget that the criticism in Washington about what is perceived as a low commitment to NATO by Germany (including not reaching the 2% in Defence expenses) predates President Trump and will likely continue during future administrations – Robert Gates, then Secretary of Defence of President Obama, warned about the gap ‘between those willing and able to pay the price and bear the burdens of commitments, and those who enjoy the benefits of NATO membership but don’t want to share the risks and the costs’ (Shanker, 2011).

The question is, what should Germany and the EU do as a response? France has long been uncomfortable with the trade-off that allows NATO to be the main security guarantee for Europe, while Germany traditionally has accepted and even welcomed it. Why? In my views, that is in no small part because it allows Berlin to avoid difficult questions about its defence policy and capabilities while its security is guaranteed in the middle of a secure and peaceful Europe. As Trump’s recent threats to withdraw US troops in Germany show (Hill, 2020), Berlin can no longer avoid at least considering these questions.

The discomfort with the new unilateralism (“America First” and the devaluing of NATO) by President Trump have led to successive public statements by German leaders in favour of a more autonomous European defence, namely the aforementioned Merkel declaration of the need for Europeans to take the future into their own hands; furthermore, Germany has used its leadership to go past the speeches into concrete action, namely with PESCO, which promises to shape the future of the CSDP for at least the next decade under a Germany-promoted concept of inclusive vision for all members of the EU. If France and Germany convince the rest of the EU members that they must strengthen their own defence capacity in order to gain greater autonomy from Washington, the evolution of the CSDP can accelerate significantly in the medium term.

The biggest test, as always, will be if EU member states are willing to put their money where their mouths are and to accept an increase in defence budget costs, a choice that many EU countries, starting with Germany, seem to remain very reluctant to take. They may no longer afford this luxury in the years to come when the world seems more and more dominated by security threats and Great Powers competitions.

References

Agence France Press (2017). ‘Trump fires up German debate on military spending’. The Local. https://www.thelocal.de/20170224/trump-fires-up-german-debate-on-military-spending

Algieri, Franco; Bauer, Thomas and Brummer, Klaus (2006). ‘Germany and ESDP’ in “The Big 3 and ESDP”. Bertelsmann Stiftung. European Foreign and Security Policy – No. 5. https://www.ies.be/files/private/8)%20Brummer%20-%20Big%203%20and%20ESDP.pdf

Baldwin and Giavazzi (2015). ‘The Eurozone crisis: A consensus view of the causes and a few possible solutions’. https://voxeu.org/article/eurozone-crisis-consensus-view-causes-and-few-possible-solutions

Baun, Michael J. (1996). ‘The Maastricht Treaty as High Politics: Germany, France, and European Integration’. Political Science Quarterly. Vol. 110, No. 4 (Winter, 1995-1996), pp. 605-624

Bendiek, Annegret (2016). ‘The Global Strategy for the UE’s Foreign and Security Policy’. Stiftung und Wissenschaft Politik. SWP Comments 38. August 2016

Bittner, Jochen (2019). ‘The World Used to Fear German Militarism. Then It Disappeared’. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/23/opinion/the-world-used-to-fear-german-militarism-then-it-disappeared.html

Brockmeier, Sarah (2013). ‘Germany and the Intervention in Libya’. Global Politics and Strategy. Volume 55, 2013 – Issue 6

Brunsden, Jim and Chazan, Guy (2018). ‘Merkel backs Macron’s call for creation of European army’. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/3f5c6c74-e752-11e8-8a85-04b8afea6ea3

Bulmer, Simon and Paterson, William E. (2015). Germany and the European Union: Europe’s Reluctant Hegemon?. Red Globe Press. London

Bundesministerium der Verteidigung (2016). White Paper on Security Policy and the Future of the Bundeswehr

Bundesministerium der Verteidigung (2018). ‘LETTER OF INTENT CONCERNING THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE EUROPEAN INTERVENTION INITIATIVE (EI2)’. https://www.bmvg.de/resource/blob/25706/099f1956962441156817d7f35d08bc50/20180625-letter-of-intent-zu-der-europaeischen-interventionsinitiative-data.pdf

Bundespräsidialamt (2014). ‘Germany’s Role in the World: Refections on Responsibility, Norms, and Alliances’, Speech by Federal President Joachim Gauck at the Opening of the Munich Security Conference, 31 January 2014, Munich: http://www.bundespraesident.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Reden/2014/01/140131-Muenchner-Sicherheitskonferenz-Englisch.pdf?__blob=publicationFile

Chassany, Anne-Sylvaine (2018). ‘France to increase military spending’. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/fede4e5a-0cb0-11e8-8eb7-42f857ea9f09

Cunningham, Paul (2018). ‘One year on – the price of joining PESCO’. RTE Politics. https://www.rte.ie/news/politics/2018/1230/1019537-pesco-ireland/

Deutsche Well (2018). ‘Germany’s lack of military readiness ‘dramatic,’ says Bundeswehr commissioner’. https://www.dw.com/en/germanys-lack-of-military-readiness-dramatic-says-bundeswehr-commissioner/a-42663215

Daehnhardt, Patricia (2015). ‘The crisis in Ukraine and Germany: the new paradigm of European strategic leadership’. International Relations, no. 45, March 2015, pp. 5-24.

Erlanger, Steven (2019). ‘Merkel and Macron Publicly Clash Over NATO’. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/23/world/europe/nato-france-germany.html

European Commission (2016). ‘Global strategy for the foreign and security policy of the European Union’

European Council (2017). ‘Defence cooperation: Council establishes Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), with 25 member states participating’. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2017/12/11/defence-cooperation-pesco-25-member-states-participating/

Gauck, Joachim (2014). ‘Germany’s Role in the World: Refections on Responsibility, Norms, and Alliances’, Speech by German Federal President at the Opening of the Munich Security Conference, 31 January 2014. http://www.bundespraesident.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Reden/2014/01/140131-Muenchner-Sicherheitskonferenz-Englisch.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

Götz, Roland (2007). ‘Germany and Russia – Strategic Partners’. Geopolitical Affairs, 4/2007.

Hill, Jenny (2020). ‘Why Trump’s plan to withdraw US troops has dismayed Germany’. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53077829

Hyde-Price, Adrian (2018). ‘The Common Security and Defence Policy’ in “The Handbook of European Defence Policies and Armed Forces” by Hugo Meijer and Marco Wyss

Keohane, Daniel (2018). ‘The Ambiguities of Franco-British Defense Cooperation’. https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/75298

Koenig, Nicole (2018). ‘The European Intervention Initiative: A look behind the scenes’. Hertie School – Jacques Delors Centre. Policy Brief. https://www.delorscentre.eu/en/publications/detail/publication/the-european-intervention-initiative-a-look-behind-the-scenes/

Koenig and Walter-Franke (2017). ‘FRANCE AND GERMANY: SPEARHEADING A EUROPEAN SECURITY AND DEFENCE UNION?’. Jacques Delors Institute Berlin. Policy Paper 202. 19 July 2017.

Krotz, Ulrich e Maher, Richard (2011). ‘International Relations Theory and the rise of European Foreign and Security Policy’. World Politics 63, no.3 (July 2011), pp. 548-79

Kundnani, Hans (2015). The paradox of German power. New York : Oxford University Press

Kunz, Barbara (2015). “Germany’s Unnecessary hegemony: Berlin’s Seeking of ‘Tranquility, Profit and Power’ in the Absence of Systemic Constraints. POLITICS. 2015. Vol.35(2), pp.172-182

Kunz, Barbara (2018). ‘The Three Dimensions of Europe’s Defense Debate’. German Marshall Fund Policy Brief. 2018, No. 024

Kwiatkowska-Drożdż, Anna and Popławski, Konrad (2014). “The German reaction to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict – shock and disbelief”. https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-commentary/2014-04-03/german-reaction-to-russian-ukrainian-conflict-shock-and

Major, Claudia and Mölling, Christian (2019) – ‘Franco-German Differences Over Defense Make Europe Vulnerable’. https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/75937

Matthijs, Matthias (2016). ‘The Three Faces of German Leadership’. Survival. Global Politics and Strategy. Volume 58, 2016 – Issue 2, pp. 135-154

Maull, Hanns W. (2018). ‘Reflective, Hegemonic, Geo-economic, Civilian … ? The Puzzle of German Power’. German Politics, Volume 27, 2018 – Issue 4: Germany’s Eastern challenge: A ‘Hybrid Ostpolitik’ in the Making?, pp.460-478

Menon, Anand (2010). ‘Power, Institutions and the CSDP: The Promise of Institutionalist Theory’. Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol.49, nº1, pp. 83-100

Meiritz, Annett (2015). ‘How Germany became Europe’s moral leader on the refugee crisis’. https://www.vox.com/2015/9/11/9307209/q-a-germanys-leadership-role-in-the-european-migrant-crisis

Ministère des Armées (2017). ‘2017 Strategic Review of Defence and National Security’

Ministère des Armées (2018). ‘European intervention initiative’. https://www.defense.gouv.fr/english/dgris/international-action/l-iei/l-initiative-europeenne-d-intervention#:~:text=European%20intervention%20initiative&text=The%20European%20Intervention%20Initiative%20(EI2,signing%20a%20Letter%20of%20Intent.

Munich Security Report (2019). “France and Germany: European Amis’

Pachta, Lukáš (2003). ‘France: driving force of the EU Common Foreign and Security Policy?’. http://pdc.ceu.hu/archive/00002117/01/France_Lukas_Pachta.pdf

Pannier, Alice (2018). ‘France’s Defense Partnerships and the Dilemmas of Brexit’. German Marshall Fund Policy Brief. 2018, No. 022

Paravicini, Giulia (2017). “Angela Merkel: Europe must take ‘our fate’ into own hands. Politico Europe. https://www.politico.eu/article/angela-merkel-europe-cdu-must-take-its-fate-into-its-own-hands-elections-2017/

Paterson, William E. (2011). ‘The Reluctant Hegemon? Germany Moves Centre Stage in the European Union’. Journal of Common Market Studies 49 (2011), pp.57–75

Pond, Elizabeth (2015). ‘Germany’s Real Role in the Ukraine Crisis’. Foreign Affairs 94/2 (March 2015), pp.173–6

Sanders IV, Lewis (2018). ‘Germany cautious as France leads European defense initiative’. Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/en/germany-cautious-as-france-leads-european-defense-initiative/a-46201409

Schweiger, Christian (2014). “The ‘Reluctant Hegemon’: Germany in the EU’s Post-Crisis Constellation” in The European Union in Crisis: Explorations in Representation and Democratic Legitimacy. Springer: Kyriakos Demetriou, pp.3-14

Shanker, Thom (2011). “Defense Secretary Warns NATO of ‘Dim’ Future”. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/11/world/europe/11gates.html

Sprenger, Sebastian (2019). ‘Germany’s plan to boost defense spending hits a snag’. DefenseNews. https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2019/02/05/germanys-plan-to-boost-defense-spending-hits-a-snag/

Stelzenmüller, Constanze (2016). ‘Germany, Between Power and Responsibility’, in William A Hitchcock, Melvyn Leffler and Jeffrey A. Legro (Eds.), Shaper Nations: Strategies for a Changing World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, pp.53–69 (Ch.3)

Stratfor (2018). ‘Europe: France’s Plans For a Military Intervention Initiative Outside the Confines of the UE’. https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/europe-frances-plans-military-intervention-initiative-outside-confines-eu

The Economist (2013). ‘Germany and Europe: The Reluctant Hegemon’, 15 June 2013

The Economist (2017). ‘The Macron plan for Europe’, 9 November 2017

Von der Leyen (2019). ‘German Defense Minister: The World Still Needs NATO’. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/natosource/germany-s-defense-minister-the-world-still-needs-nato/

Von Krause, Ulf (2018). ‘The 2-Percent Objective and the Bundeswehr: Discussion about the German Defence Budget’. Federal Academy for Security Policy. Security Policy Working Paper, No.23/2018

Zandee, Dick (2016). ‘UE Global Strategy: from design to implementation’. Available at https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/UE%20Global%20Strategy%20-%20AP%20-%20August%202016.pdf

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Germany, Europe and Potential Outcomes of the Ukraine War

- The European Union’s Security and Defence Policy Beyond COVID-19

- Germany and the New Global Order: The Country’s Power Resources Reassessed

- Grexit and Brexit: Lessons for the European Union

- Brexit and the 2019 European Elections

- The UK’s Global Role Post-Brexit: What is Worth Researching?