The recent global Black Lives Matter protests have prompted IR scholars and others to revisit the work of Malcolm X and the poetry of Gil Scott-Heron. In one of his prison letters, Malcolm X wrote that he became “a real bug for poetry. When you think back over all of our past lives, only poetry could best fit into the vast emptiness created by men.” Later in his life, Malcolm X sought to internationalize the plight of African Americans. For example, at the Organization of African Unity in 1964, he exhorted the African diplomats and others that “We, in America, are your long lost brothers and sisters, and I am here to remind you that our problems are your problems.” Malcolm X looked to internationalize the sensibilities of the attendees by saying of African Americans: “We stand defenseless at the mercy of American racists who murder us at will for no reason other than we are black and of African descent.” Before his assassination, Malcolm X pushed for centers for black artistic expression as part of a means to connect black people throughout the globe. After his death, “this energy coalesced into the Black Arts Movement.” In this movement, poetry and other forms of art were critical to speaking truth to power and working toward justice for the dispossessed and disenfranchised—domestically and globally.

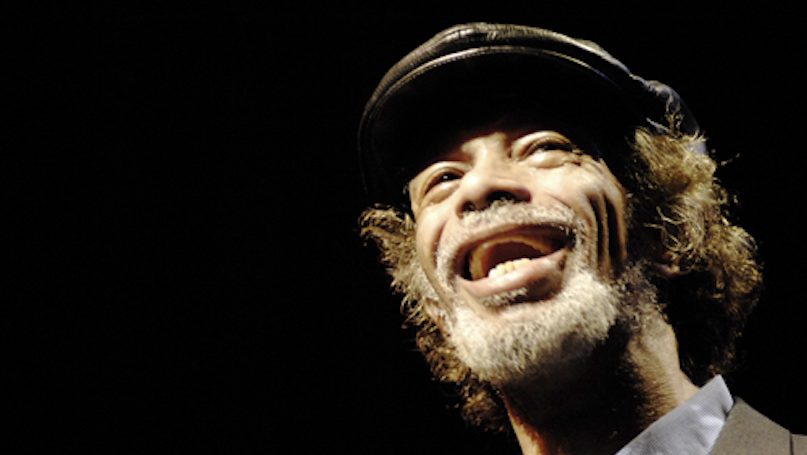

Gil Scott-Heron is perhaps one of the most famous artists influenced by this movement. In this essay, we briefly outline why we have turned to Gil Scott-Heron’s poetry in the classroom. His poetry, inspired by Malcolm X, is particularly relevant to this moment as we witness the momentum of Black Lives Matter protests happening in all 50 states and all over the world from Belgium to Brisbane. Thousands marched in Paris. From Kentucky to Canada, from Fresno to Frankfurt thousands are looking at the police brutality visited upon African Americans and seeing similarities to how state-sponsored police forces act against people of color and poor people in their own milieu. Chinese, Russian, and Iranian diplomats are focusing attention, however fleeting and for their own purposes, on the treatment of African Americans. In the classroom, whom might we listen to and how might we speak about these global protests? Gil Scott-Heron, we think, helps us confront the complexities of this moment.

Throughout this year, we have been co-teaching a “Poetry and Politics” seminar. One of the poems that we have been teaching together is Scott-Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.” The poem is helpful in thinking about this global moment of Black Lives Matter for several reasons.

First, it helps us think critically about the media’s focus on looting rather than structural sources of protests and riots (“There will be no pictures of you and Willie Mae pushing that shopping cart down the block on the dead run / Or trying to slide that color TV into a stolen ambulance”). As we witnessed in recent weeks, the media tends to zoom in on certain newsworthy effects (e.g. fires, looting, and property damage) of structural racism rather than structural racism itself. The Revolution tells us that “there will be no pictures of pigs shooting down brothers on the instant replay.” The Revolution prompts a discussion about the reasons for the disparaging term for police, and, more importantly, pushes us to reflect on the many black men (and women) killed not only by law enforcement officers but by law enforcement structures—portrayed in certain media reports as though these killings are a sport replete with “instant replay.”

Second, Scott-Heron offers a poetic window into divisions within black movements, reminding us of how these movements are never monolithic and often have different objectives (or means of achieving them). For example, The Revolution involves a biting critique of civil rights leaders Roy Wilkins and Whitney Young. During the heady days of the orthodox civil rights movement, the grassroots activities were led by the “Big Six.” Amongst the Big Six were longtime labor organizer A. Philip Randolph, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., James Farmer, and a young John Lewis. Scott-Heron turns his pen towards the last two of the “Big Six:” Whitney Young and Roy Wilkins of the National Urban League and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, respectively.

Scott-Heron’s pen grows teeth when he writes “there will be no pictures of Whitney Young being run out of Harlem on a rail with a brand new process. There will be no slow motion or still lifes of Roy Wilkins strolling through Watts in a red, black and green liberation jumpsuit that he has been saving for just the proper occasion.” Why does Scott-Heron use his pen to bite two of the most respected leaders of the civil rights movement? While Young and Wilkins were symbols of articulate moral leadership and effective advocacy in black communities, Scott-Heron muses about Young in a process (straightened hair) and Wilkins in a Bendera flag jumpsuit. Young and Wilkins were always seen in a dark fitted suit with a white shirt, a thin dark tie, and close-cropped natural hair. Putting them in a process and a multi-colored jumpsuit is arguably worse than putting them in a red nose with big floppy shoes piled up in a Volkswagen bug.

Why this imagery? Here, we see Scott-Heron launching two critiques. First, he is voicing a common criticism that Young and Wilkins were too close to white philanthropy to provide effective street-based leadership for black communities. Second, Scott-Heron is identifying both Young and Wilkins as outside the revolution, as irrelevant to the revolution and likely even as counter-revolutionaries that should be scorned by politicized black communities. Using Young and Wilkins as stand-ins to criticize the “establishment” leadership of the “Big Six,” Scott-Heron turns his lens on the social and class divisions in black communities and finds a key fissure between middle-class blacks and the identity of the communities that birthed them. For students unaware of these kinds of divisions, Scott-Heron could prompt conversations about how and why they emerge, and also what they mean for bringing about both domestic and global change.

Third, Scott-Heron is pressing us to consider how black struggles can be domesticated or commercialized. As the world watches the protests and “instant replays” of George Floyd’s murder, we might ask what it means that “the revolution will not be televised?” The world finally seems to be watching. But what are we watching? Who is watching and what do we see (and fail to see)? Scott-Heron tells us that “the revolution will not go better with Coke.” How might revolution be domesticated by calls for cosmetic improvements without deeper systemic change? How might revolution be commercialized and co-opted? The Revolution leaves us searching—pragmatically and imaginatively—for difficult answers to so many pressing questions.

Considering The Revolution in the context of Black Lives Matter also reminds us of the deep connections between black political struggles in the United States and global struggles discussed within the annals of black political thought. W. E. B. DuBois held the first of the historic Pan African Conferences in 1919 locating the plight of African Americans within the overall anti-colonial struggle. The clergyman and diplomat Alexander Crummell wrote about internationalizing the anti-racist/anti-fascist struggle of African Americans in 1861 in his letter, The Relations and Duties of Free Colored Men in America to Africa. And as early as 1852, the veritable “Father of Pan Africanism” Martin Delany published The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States, where he says the facts of American oppression of African Americans are plain and the goal is to “proclaim in tones more eloquently than thunder” that this treatment requires an international reaction.

The Black Lives Matter movement, emerging from black struggles in the streets of the United States, has become a global response to systemic racism. The death of Adama Traoré outside of Paris is seen as connected to the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Chants in Paris include the phrase, “Justice pour Adama, Justice pour George Floyd, Justice pour Tous!” How do we respond to this moment in the classroom? A turn to poets like Gil Scott-Heron, we believe, is one productive way to reflect on this juncture. His poems distilled wordplay, irony, anger, intellect, and lament into some of the most illuminating poems and songs ever produced in the world. While his work contends with the sociopolitical brutalities of racism, it also signals toward the possibilities (and impossibilities) of change—in the world and within ourselves. As we read his poetry with students in the context of Black Lives Matter, change in the world (we hope) becomes more possible. Guided by the spirits of Malcolm X and Gil Scott-Heron, we are searching, together. What will we find? What will we create? How might poems of the past and present inform and inspire the change we are working toward?

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Racial Injustice and the Erosion of America’s Global Standing

- Towards an ‘American Spring’ of Justice and Equality?

- Opinion – Black and Southern Feminisms Matter in the Global Climate Struggle

- Opinion – Transgressive Pedagogy in International Studies: A European Case Study

- Inclusiveness, Pedagogy, Identity, Ideology, and the Epistemology of the Professor

- BDS and BLM: Positionality, Intersectionality and Nonviolent Activism