Since its eruption in May 2014, the Second Libyan Civil War has been marked by the multitude of national and international actors involved and their dynamic interest constellations. But regardless of their rivalries, all conflict parties have continually shared a common concern for the country’s primary natural resource: oil. The United Nations Security Council has addressed the importance of the resource shortly before the start of the civil war and declared that only the Libyan government can export crude oil (UN Security Council, 2014). But soon after, the civil war started, and two rivalling governments claimed to be internationally recognised. With ongoing unclarity of which actor could lawfully export oil, in the first phase of the civil war, multiple militias controlled Libya’s oil fields, storages and refineries (Costantini, 2016, p. 415).

Then in 2015, after the Libyan Political Agreement was signed, the United Nations (UN) acknowledged the newly formed Tripoli-based Government of National Accord (GNA) as only legitimate government (UN Security Council, 2015). Since then, the United Nations supervise that all Libyan crude oil exports are handled through the GNA’s National Oil Corporation (NOC) and Libyan Central Bank (LBC). But five years later, little academic literature has addressed the consequences that the UN’s decision since had on the oil economy. This paper addresses this gap and answers the question: what effect did the United Nations have on the Libyan civil war oil economy since the 2015 Libyan Political Agreement?

To do so, this research draws on the existing academic literature on the roots of Libya’s war economy (Paoletti, 2011; Pack, 2019) and the war economy during the first civil war (Costantini, 2016). Furthermore, it benefits from research into the UN’s actions (Mezran & Varvelli, 2017) and Libya’s current war economy (Eaton, 2018). Based on these insights, this paper evaluates the positive and negative consequences of the UN’s actions, which is helpful for policymakers and academics alike. Furthermore, media reports on the role of oil in the conflict frequently ignore that the resource not only plays a crucial role for the warring parties but also smugglers and civilians. Due to the complexity of the oil economy, Libya presents an excellent case study on the consequences of the UN’s actions.

In the next section, different resource-related UN conflict management tools will be defined. Additionally, the concept of war economies and their interrelated sub-aspects of combat, shadow and coping economies will be presented. Afterwards, the background to the Second Libyan War will be briefly summarised and the UN Security Council Resolution and the Libyan Political Agreement as a commodity sanction examined. Then, the analysis will illuminate how the UN’s crude oil sanction indirectly induced a revenue-sharing agreement between opposing military parties. Furthermore, it will be shown that the UN’s sanction was unable to stop all illicit activities and that many Libyans depend on the crude oil revenue-sharing between opposing conflict actors. Finally, some research limitations and the conclusion will be presented.

Theoretical framework

A lot of academic attention has focused exclusively on the consequences of the UN’s conflict management (Mack & Khan, 2000), the role of resources in conflicts (Le Billon, 2001) or war economies (Liebenberg, Haines & Harris, 2015). This study connects these dimensions, by drawing on Le Billon and Nicholls’ (2007) research on the effects of resource-related conflict management instruments. Le Billon and Nicholls (2007, p. 615) claim that commodity sanctions and revenue-sharing are two of the UN’s main types of commodity-related conflict management tools. Resource-related economic sanctions either prohibit the import or export of a commodity (Le Billon & Nicholls, 2007, p. 616). Revenue-sharing, on the other hand, offers conflict actors to keep their resources, get part of the resources of another conflict party or takes the form of monetary transfers between conflict parties (Le Billon & Nicholls, 2007, p. 617). These two resource-related conflict management instruments are not the only available options to the UN, but sufficient for analysing its actions in Libya.

For the analysis of the consequences of the UN’s instruments on Libya’s civil war oil economy, a definition of war economies is required. In general, a war economy encompasses all economic endeavours, which are related to the continuation of conflict (Eaton, 2018, p. 5). It is useful to further distinguish between three aspects of war economies: combat, shadow and coping economies (Goodhand, 2005, p. 192).

The combat economic aspect entails the production and allocation of all economic assets, which are directly employed to continue the war (Goodhand, 2005, p. 202). Hence, the Libyan combat economy of oil encompasses all measures by actors to use oil for sustaining their military efforts. The shadow economy, on the other hand, includes all those actors who do not fight themselves but want to profit from a conflict (Goodhand, 2005, p. 204). Furthermore, some actors are part of the so-called coping economy and use a conflict-related resource to sustain themselves (Goodhand, 2005, p. 206). The distinction between these three facets of war economies will be crucial for the following analysis of how the UN’s oil-related instruments have affected different oil-dependent actors.

Analysis

War background and the Libyan Political Agreement

For decades before the 2011 First Libyan Civil War and overthrow of dictator Muammar al-Gaddafi, Libya’s economy has almost exclusively been dependent on oil exports (Paoletti, 2011, p. 318). After the First Civil War, the new government failed to stabilise the country and protect its oil assets. In 2014, the UN Security Council reacted and in Resolution 2146 declared that only the Libyan government can lawfully export the country’s crude oil. However, this decision initially had little meaning, as shortly after, the Second Civil War erupted and several governments claimed legitimacy (Pack, 2019, p. 11). Then, in 2015, the Libyan Political Agreement was signed between several of the conflict parties and its resulting Government of National Accord (GNA) accepted as legitimate by the UN (UN Security Council, 2015).

Following Le Billon and Nicholls’ typology of resource-related conflict management instruments, UN Security Council Resolution 2146 together with the recognition of the GNA, was a resource-related economic sanction. The Security Council (2015) declared that solely the GNA can export crude oil and that the National Oil Corporation and Central Bank should accept the GNA’s full authority. While the UN’s intention was to strengthen the GNA by sanctioning all other actors from exporting oil, the next section will show that the consequences on the oil economy were manifold.

Effects on the combat economy

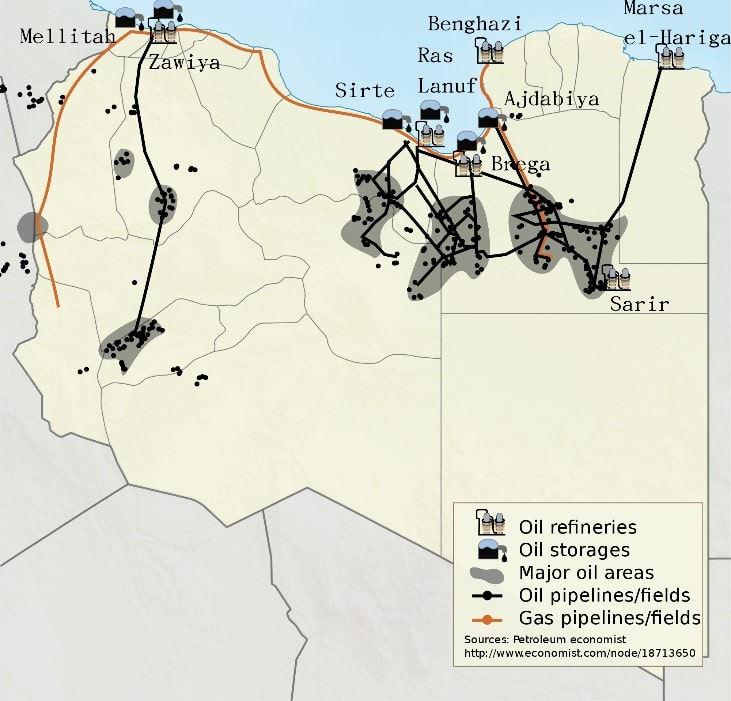

The UN sanctions clearly stated that only the GNA’s National Oil Corporation (NOC) can export crude oil but did not address who can control Libya’s oil fields and refineries. Right after the Libyan Political Agreement, the GNA was still in control of the western and parts of the eastern oil infrastructure and for a while, the combat economy process of oil was rather straightforward (for map see Appendix A; Mezran & Varvelli, 2017, p. 130). The GNA protected the oil fields and the NOC with its subsidiaries took care of refining oil for the domestic market or exporting crude oil internationally (Mason, 2018). The revenue of these exports was received by the central bank, which used the money to pay public salaries and the GNA’s military apparatus (Mezran & Varvelli, 2017, p. 62). Hence, by controlling and exporting the oil, the GNA was able to finance its military operations.

But despite the UN’s oil export sanctions, non-governmental conflict parties were also interested in controlling the oil infrastructure to sustain their own war efforts. The Libyan National Army (LNA), led by General Haftar, crystallised as the most powerful enemy of the GNA and seized authority of the major Eastern oil infrastructure in 2015 and 2016 (Mezran & Varvelli, 2017, p. 130). Haftar’s LNA has tried to export its oil independently and bypass the UN sanctions but failed to do so (Reuters, 2020). Thus, the UN’s oil sanction was successful in constraining the GNA’s main opponent, the LNA to not being able to export oil itself.

Then, because Haftar’s LNA was unable to export crude oil, and the NOC was only able to continue the high level of oil exports if the LNA opens its fields, both sides decided to cooperate (Eaton, 2018, p. 32). The cooperation was beneficial for the NOC, as the UN sanctions guaranteed its complete export authority, which meant that it would remain in control of the cooperation (Mezran & Vavrelli, 2017, p. 62). Haftar, on the other hand, used the cooperation to demand part of the export revenues and present himself as the strong guarantor of oil exports to the international community (Mezran & Varvelli, 2017, p. 15).

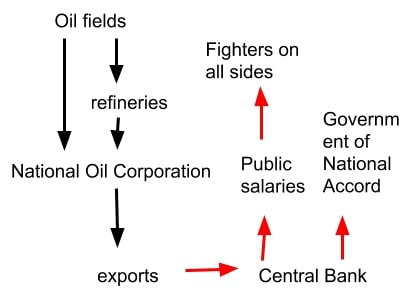

Out of these circumstances the peculiar Libyan oil combat economy, which is shown in Figure 1 below, emerged. In Libya, regardless of whether the LNA or GNA control an oil field, the commodity is brought to refineries for the Libyan market or exported as crude oil (Lewis, 2020). Because of the UN sanction, the NOC is in complete control of this process. Then, the GNA’s central bank receives the payments for the oil exports and pays public salaries with them (Lewis, 2020). Strikingly, these payments are received by fighters of both the GNA and the Haftar’s LNA (Mezran & Varvelli, 2017, p. 62). Hence, the GNA’s central bank sustains the conflict by paying both armies’ salaries.

Figure 1: Combat Economy Flows

While intended to be a commodity sanction on non-GNA actors, the UN Security Council has indirectly induced a situation of revenue-sharing between the GNA and LNA. Because the LNA is in control of many of Libya’s oil sites but cannot export it and the GNA can export oil but does not control many sites, both conflict parties share the revenue of the exports via the central bank. Using Le Billon & Nicholls’ typology (2007, p. 617), the arrangement between the GNA and Haftar’s LNA is a revenue-sharing mechanism via monetary transfers. Arguably, Haftar has used this revenue-sharing agreement for his benefit, as by 2020 he managed to seize control of all Libyan oil fields including those in the west (see Appendix A; Aljazeera, 2020). In 2020, the LNA started to use this control to shut down the country’s oil infrastructure and to demand a larger share of the oil export revenues (Wintour, 2020). And despite the UN Security Council’s (2020) calls to stop, the LNA has continued to block oil facilities to weaken the GNA, costing both conflict parties billions in lost revenues (Reuters, 2020).

Overall, the UN’s commodity sanction indirectly led to a revenue-sharing agreement in which both the LNA and GNA were cooperating in oil production and thereby financed their military efforts. This meant that the oil infrastructure was kept protected but also that both the GNA and LNA could continue to finance their fight against each other. The last months, then, have shown the instability of this revenue-sharing agreement.

Effects on the shadow economy

The UN’s commodity sanction also had ambiguous effects on Libya’s illicit oil economy. The sanction of crude oil exports has been successful in stopping non-conflict actors from exporting crude oil but failed to prohibit smuggling of refined oil (Eaton, 2018, p. 14). The smugglers use the chaos of the ongoing conflict to hijack fuel transports, which they then resell at higher prices or export abroad. Some of them are also involved in the GNA or LNA, which indicates that both conflict parties partly profit from refined oil smuggling (Eaton, 2018, p. 16). Anyhow, Libya’s tax returns in general, are negatively affected, as around 30% of Libya’s refined oil is smuggled, which creates a yearly tax loss of $1.8 billion (Eaton, 2018, p. 14). Only in 2018, did the UN Security Council (2018) decide to explicitly extend its crude oil export sanction to refined fuel. But up to this date, little data on the new sanction’s effectiveness in curbing smuggling exists.

Additionally, the UN Security Council’s (2015) demand that all oil infrastructure should be supervised by the NOC has not always been adhered to by war profiteers. Occasionally, local actors managed to control some of the oil infrastructure and blackmail the NOC into paying them to leave (Eaton, 2018, p. 22).

Therefore, the UN has not managed to completely contain Libya’s shadow economy with its sanction. Illicit actors have been unable to export crude oil but highly profited from refined fuel smuggling. The UN has been late to explicitly sanction refined fuel smuggling and did not prevent illicit actors from capturing oil infrastructure for blackmail attempts.

Effect on the coping economy

In Libya, not only conflict parties and illicit actors but also most everyday citizens depend on oil revenues. More than 95% of state revenues come from oil and gas (Eaton, 2018, p. 23) and in 2010 around 85% of all Libyans were employed by the state (Costantini, 2016, p. 408). The exact numbers might have altered recently, but nevertheless plainly indicate how crucial the resource is for guaranteeing the living standard of most of society. The UN recognised this importance and underlined that exports must work for the benefit of all Libyans.

The UN’s crude oil sanction has guaranteed that no non-governmental actor can export crude export and that hence all revenues at least partly help to pay the crucial public salaries. But despite the sanctions, many civilians feel that to sustain themselves they need to smuggle small loads of refined fuel (Eaton, 2018, p. 22). The sanctions were more successful in indirectly inducing the LNA-GNA revenue-sharing agreement, which means that both main actors are interested in protecting oil infrastructure for the benefit of Libyans. But the last months have also shown that the LNA still has uses oil blockades to demand a higher share of export revenues. The blockades, if lasting longer, could have devastating impacts on Libyans’ living standards, as the central bank would not be able to the pay public salaries, on which so many people rely (Reuters, 2020).

In sum, the UN’s crude oil sanction has helped everyday Libyans by ensuring that crude oil cannot be exported without contributing to their salaries. The sanction has also indirectly led to the GNA and LNA’s revenue-sharing mechanism, which for a long time guaranteed continued exports of the oil, on which Libyans rely. However, the UN’s sanctions did not prevent the LNA’s recent oil blockade, which threatens the living standard of many. And whilst the conflict is ongoing, many Libyans might continue to sustain themselves with illegal activities.

Limitations and further research

This shows that a clear distinction between military parties, illicit actors and normal citizens is sometimes difficult. Hence, the preceding division into combat, shadow and coping oil economy consequences is to some extent artificial and only intended to clarify the UN sanctions’ fallout on different facets of Libya’s oil economy. Further research could investigate how external governments and corporate interests in Libya influenced the UN’s sanctions and scrutinise the links between military and illicit actors. But above all, proposals for improving the UN’s resource-related conflict management tools are urgently needed.

Conclusion

Overall, the UN’s crude oil commodity sanction on all non-governmental actors had manifold consequences on the Libyan civil war oil economy. The sanction succeeded in prohibiting non-governmental crude oil exports but did not strengthen the UN-backed GNA. That is because the LNA took over most of the oil infrastructure and the GNA and LNA agreed to a revenue-sharing agreement of exports. Thereby, oil exports continued, but it also allowed both the GNA and LNA to finance their war efforts, which prolongs the conflict. The crude oil sanction has guaranteed that normal citizens profit from oil exports, but the recent LNA infrastructure blockades and demands for higher export revenue shares show that the UN’s sanction is not sufficient to guarantee that Libyans can sustain themselves. Furthermore, the UN was late to sanction non-governmental refined fuel exports, which allowed for a vibrant shadow economy of smugglers to emerge.

In sum, the UN’s oil sanction on non-governmental actors was not able to shorten the civil war, nor contain refined fuel smuggling but at least guaranteed that Libyans could mostly continue to rely on their salaries. With the blockades in recent months, however, it became clear that the emerged GNA-LNA revenue-sharing agreement cannot resolve the conflict. In the future, the UN can learn from the ambiguous consequences of its oil sanction and aim to better tackle the complex facets of Libya’s civil war oil economy.

References

Aljazeera (2020). Commander Khalifa Haftar’s forces choke Libya’s oil flow. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/ajimpact/commander-khalifa-haftar-forces-choke-libya-oil-flow-200119162228201.html

Costantini, I. (2016). Conflict dynamics in post-2011 Libya: a political economy perspective. Conflict, Security & Development, 16(5), 405-422.

Eaton, T. (2018). Libya’s War Economy. Predation, Profiteering and State Weakness. Chatham House Research Paper. Retrieved from https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/files/chathamhouse/publications/research/2018-04-12-libyas-war-economy-eaton-final.pdf

Goodhand, J. (2005). Frontiers and wars: the opium economy in Afghanistan. Journal of Agrarian Change, 5(2), 191-216.

Le Billon, P. (2001). The political ecology of war: natural resources and armed conflicts. Political geography, 20(5), 561-584.

Le Billon, P., & Nicholls, E. (2007). Ending ‘resource wars’: Revenue sharing, economic sanction or military intervention?. International Peacekeeping, 14(5), 613-632.

Lewis, A. (2020). Factbox: Libya’s oil industry caught in middle of power struggle. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-libya-oil-factbox/factbox-libyas-oil-industry-caught-in-middle-of-power-struggle-idUSKBN1ZN23A

Liebenberg, S., Haines, R., & Harris, G. (2015). A theory of war economies: Formation, maintenance and dismantling. African security review, 24(3), 307-323.

Mack, A., & Khan, A. (2000). The efficacy of UN sanctions. Security Dialogue, 31(3), 279-292.

Mason, N. (2018). To stabilize Libya, redistribute oil revenue. Atlantic Council. Retrieved from https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/to-stabilize-libya-redistribute-oil-revenue/

Mezran, K., & Varvelli, A. (2017). Foreign Actors in Libya’s Crisis. Atlantic Council. Ledizioni: Milano.

Pack, J. (2019). It’s the Economy Stupid: How Libya’s Civil War Is Rooted in Its Economic Structures. Instituto Affari Internazionali Papers.

Paoletti, E. (2011). Libya: Roots of a civil conflict. Mediterranean Politics, 16(2), 313-319.

Reuters (2020). Blockade of oil facilities has cost Libya $4 bln – NOC. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/libya-oil/blockade-of-oil-facilities-has-cost-libya-4-bln-noc-idUSC6N2AK00H

UN Security Council (2014). Resolution 2146 (2014). Retrieved from https://www.undocs.org/S/RES/2146%20(2014)

UN Security Council (2015). Resolution 2259 (2015). Retrieved from https://undocs.org/S/RES/2259(2015)

UN Security Council Demand (2018). Resolution 2441 (2018). Retrieved from http://unscr.com/en/resolutions/doc/2441

UN Security Council (2020). Resolution 2510 (2020). Retrieved from http://unscr.com/en/resolutions/doc/2510

Wikipedia (2011). Libya location map-oil & gas 2011. Retrieved from https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Libya_location_map-oil_%26_gas_2011-en.svg

Wintour, P. (2020). Libya oil production nosedives as Haftar ignores calls to end war. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jan/20/libya-oil-production-nosedives-khalifa-haftar-ignores-calls-end-civil-war

Appendix

Libya Oil Location Map

Written at: University of Amsterdam

Written for: Nel Vandekerckhove

Date written: May 2020

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Limitations and Capabilities of the United Nations in Modern Conflict

- The Angolan Civil War: Conflict Economics or the Divine Right of Kings?

- Do Coups d’État Influence Peace Negotiations During Civil War?

- Australia on the United Nations Security Council 2013-14: An Evaluation

- Were ‘Ancient Hatreds’ the Primary Cause of the Yugoslavian Civil War ?

- Agonizing Assemblages: The Slow Violence of Garbage in the Yemeni Civil War