Humanitarian aid workers operate in some of the most dangerous places in the world. As the transboundary dimension of emergencies and their humanitarian implications change, so too do the tools developed by states and intergovernmental organizations to respond. If conflicts become more vast, violent and multidimensional, the conditions in which aid workers are deployed and operate should be even more secure. The impact of humanitarian aid workers in areas affected by war, instability, deprivation and natural disasters is becoming increasingly relevant and influential. Scholars of International Relations have broadly investigated the features and impact of the roles they play, in parallel to the changes occurring to crisis management, at all levels. Although the topic has already raised interest among scholars and practitioners, it still requires further investigations and deserves greater attention, particularly on the part of intergovernmental organization officers. The humanitarian aid worker category is a very broad one, and includes local and international NGOs, intergovernmental organisations staff, and International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) staff.

This article intends to contribute to the ongoing debate, by focusing on the security of humanitarian NGOs and stressing three main points. Firstly, IR theories on security and conflict need to be refreshed and shaped on the changes in the nature of crises and their management. Secondly, empirical analysis of reliable data is necessary to measure the lack of protection and the impact on aid workers’ performance. Thirdly, the combination of theoretical and empirical reflections can shed light on the most important challenges aid workers face and the practices they have developed to defend themselves, and ultimately generate effective policy prescriptions.

Being placed in a secure environment is essential to aid workers for providing their assistance and fulfilling their tasks in an efficient way. In conflict zones this may represent one of the biggest challenges, not always solved by international law and practices. The topic is extremely sensitive and should be read in a broader context.

It should be firstly put in relation to the multifaceted nature of contemporary humanitarian crises, whose political and humanitarian consequences require a collective response, well beyond the mandate or capacity of a single actor. Such responses not only imply the involvement of different actors, but also various civilian competencies, next to military ones (Franke, 2006; Bellamy and Williams, 2010; Wolff, 2018). Therefore, in the current humanitarian system, the relevance of non-state actors has grown, together with their ability to efficaciously intervene in those areas hardly covered by traditional peacekeeping operations. As the vast literature on humanitarian NGOs has underlined, the tasks they can cover can be placed along the whole humanitarian process, before, during and after the crisis. Next to traditional relief and assistance, innovative roles like preventive action, mediation, and peacebuilding have developed and professionalized, always in parallel with other state and intergovernmental actors (Charnovitz, 1996; Keck and Sikkink, 1998; Davies, 2014; Irrera, 2013; 2019).

Undoubtedly, more professional and widespread roles imply more insecurity. The theoretical debate has focused on the legal and moral constraints that NGOs have to face in difficult contexts, but also on the reasons and features of the attacks they suffer. In other words, if NGOs are universally recognised as neutral non-state actors at the local populations’ disposal, why they are constantly in danger while deployed? And why are they, in many cases, deliberately targeted? Quantitative investigations based on data, observing type, number and location of incidents occurred to aid workers have offered some interesting insights (Sheik et al. 2000).

On the one hand, the notion of insecurity, as an external contextual factor, has emerged (Fast, 2007). Humanitarian workers may fall victim to attacks that indiscriminately target all civilians, such as terrorist events which assault crowded spaces, like hotels, markets and religious sites. This is certainly due to the level of danger of the countries in which they are deployed, but cannot explain violence against NGOs, or why some organizations are more targeted than others (Slim, 1997; Bush, 1998, Beasley, et al. 2003; Duffield, 2014).

On the other hand, scholars have related the danger to which aid workers are subject to the ways humanitarian action is conceived and applied in the current global political system. They are more likely to be the victims of targeted attacks in specific countries, depending not only on the level of violence of conflicts but also on the presence of insurgents, guerrilla and all forms of non-state armed groups (NSAGs), which may influence the perception of aid among local populations. In countries like Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, Sri Lanka, violence is usually deliberate and humanitarian workers are the main target (Wille and Fast, 2010).

The complicity with the ‘enemy’ and being external is the most appealed argument. Although they are evidently non-armed, often connected with local civil society groups and providing help, aid workers are presented and perceived as an opposing party.

NGOs, in particular, are often seen as ‘outsiders within’ international organizations, and connected to the military forces deployed by the United Nations and the European Union, or conveyers of the Western countries’ neo-colonial commitment (Heins, 2008). This perception may confuse the roles NGOs play in the field, especially among the local communities, and is ordinarily used to justify attacks and violence against them.

Therefore, working conditions for NGOs in conflict zones can be very troublesome. The variety of tasks developed by humanitarian NGOs expose them to different dangers and consequences. Such difficulties are not always empirically measured because of the lack of reliable, accurate and comparable statistics. The incompleteness of data and the consequent imprecise reflection on the issue is also due to poor knowledge on the level, causes and consequences of exposure to violence (Fast, 2007; Sheik et al., 2000; Barnett, 2004). Non-governmental initiatives try to fill this information gap left by international agencies. Aid Worker Security Database (AWSD) is a database, compiled by Humanitarian Outcomes, a team of specialists providing policy advice for humanitarian aid agencies and donor governments. AWSD publicly offers information on major incidents of violence incurred by aid workers. It refers to a broad definition, including NGOs, ICRC, and locally contracted staff, but not UN peacekeeping personnel, election monitors or other kind of volunteers.

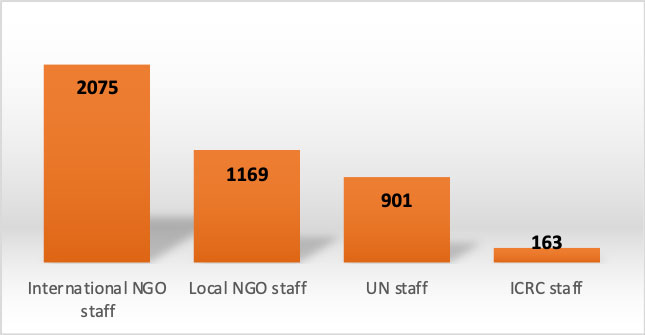

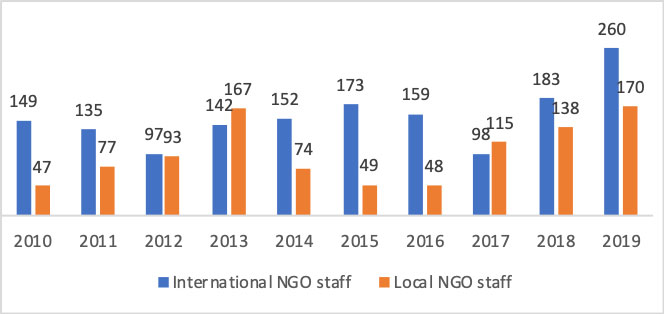

Data presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2 allows some considerations. They refer to the number of attacks occurred to aid workers in aggregate terms, including all categories of workers, in the period 2006-2019.

Fig. 1 – Attacks on aid workers – 2006-2019

Fig. 2 – Attacks on NGO aid workers – 2010-2019

Source: Humanitarian Outcomes, Aid Worker Security Database, 2020, aidworkersecurity.org

In the timeline considered, which is quite considerable and meaningful, incidents to NGOs aid workers are frequent and increasing, and particularly affect international organisations, although local ones are more and more in danger. If compared to the other categories, ICRC and UN agencies staff, it is clear that NGO workers are most and increasingly exposed to violence.

Data is also necessary for assessing specific features of incidents, beyond the overall number. More visible and mediatic events, like bombings, kidnapping and murder, easily draw the attention of media and public opinion. Rape, sexual harassment, armed robbery or individuals caught in the crossfire, are perceived as minor issues and reported only by the NGOs to their headquarters (Van Brabant, 2000; Sheik et al., 2000).

According to the AWSD, although it depends on the country in which the conflict is located, aerial bombardments, bodily assaults and arbitrary arrests and detention are the most used techniques to attack NGO workers. Syria is currently the most dangerous country, followed by South Sudan, DRC, Afghanistan, and Central African Republic (AWSD, 2020). Yemen is the last one, simply because few NGOs have been able to deploy. This is a paradigmatic example of the process of adaptation that has pushed organisations to be more aware of the risk of lethal attacks and rethink their practices (Lloyd Roberts, 2005; Stoddard et al., 2017).

Within the global humanitarian system, this is, however, a difficult process. In principle, the protected status, accorded to all humanitarian aid organisations under international humanitarian law, is extended to NGO workers. In practice, authoritarian states and non-state armed groups have repeatedly violated this norm, leaving the aid worker attacks unpunished (Stoddard et al. 2017).

One of the most striking dilemmas for NGOs is the need to make use of such status for securing workers, while remaining neutral in a conflict. The development of a solid ethical framework, which allows humanitarian actors to adapt principles to very unsecure conflict settings, is needed (Goodhand, 2000).

Additionally, NGOs are often deployed in countries in which peacekeeping operations are under way. This means that they inevitably enter into contact with the military. This is an indirect consequence of the changes in crisis management at the global level (Irrera, 2013). Civilian and hybrid missions can create a better protected environment, in which NGOs can work more proficiently. However, it can alter the perception of NGOs and neutral aid workers, and associate them with the enemy, exposing them to more danger in respect to local armed groups.

Despite such difficulties, NGOs have developed specific practices in reducing the impact of insecurity. The most radical decision is the complete suspension of activities, which has an inescapable impact on the humanitarian work which has already been provided and affects local communities. Therefore, this happens only in the most dangerous cases and when security conditions do not allow any other action. A limitation of activities and the devolvement to local organisations is more common. The choice of the so-called remote management, that is to say the drastic reduction of international and national personnel from the field, and the transfer of larger programme responsibilities to local staff or local partner organisations, is a difficult one for NGOs. It firstly impacts the direct monitoring of project implementation and coordination of local stakeholders, which is an essential part of humanitarian response. Secondly, it requires additional efforts like the adaption of ongoing programmes and projects and their technical aspects and the identification of the expertise and availability of local partners. Thirdly, it can also distress the relations with donors and the coordination with international agencies (Stoddard, Harmer and Renouf, 2010).

The security of conflict zones and the implications on aid workers is a sensitive topic, destined to produce more concern with the humanitarian system, in parallel to the changes in security and the nature of conflicts.

NGOs represent just one of the several categories of aid workers, but are certainly the most impacted, given the high professionalization of their expertise and tasks, which exposes them to the violence of terrorists and armed groups. Although attacks are constantly reported by the media and denounced in their official reports, the insecurity which is confronted by NGOs in conflict zones remains an under-researched issue. The COVID-19 outbreak has worsened the effects of conflicts in all regions, making humanitarian aid more complicated. More empirical and theoretical research and more policy analysis by scholars and practitioners are strongly required.

References

Barnett K. (2004), Security report for humanitarian organizations: Directorate-General for Humanitarian Aid, European Commission Humanitarian Aid Offce (ECHO), Brussels.

Beasley R, Buchanan C. and Muggah R. (2003), In the line of fre: Surveying the perceptions of humanitarian and development personnel of the impacts of small arms and light weapons, Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue and Small Arms Survey, Geneva

Bellamy A. and Williams P. (2010) Understanding Peacekeeping, Polity Press Cambridge.

Charnovitz, S. (1997), Two centuries of participation: NGOs and international governance. Michigan Journal of International Law, 18(2).

Davies, T. (2014), NGOs: A new history of transnational civil society. Oxford University Press.

Fast L. (2007), ‘Characteristics, context and risk: NGO in security in conflict zones’, Disasters, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 130−154.

Franke, V. (2006). The peacebuilding dilemma: Civil-military cooperation in stability operations. International Journal of Peace Studies, 5-25.

Goodhand J. (2000), ‘Research in conflict zones: ethics and accountability’, Forced Migration Review, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 12-16.

Irrera D. (2019), ‘NGOs and Security in Conflict Zones’, in T. Davies (eds), Routledge Handbook of NGOs and International Relations, Routledge, London, pp. 573-586.

Irrera D. (2013), NGOs, Crisis Management and Conflict Resolution, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

Lloyd Roberts D. (2005), Staying Alive, Safety and security guidelines for humanitarian volunteers, ICRC, Geneva.

Slim H. (1997), ‘Relief agencies and moral standing in war: Principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and solidarity, Development in Practice, vol. 7, pp. 342–352.

Sheik M. et al. (2000), ‘Deaths among humanitarian workers’, British Medical Journal, vol. 321, no. 7254, pp. 166−168.

Stoddard, A., Harvey P., Czwarno M. and Breckenridge M. (2020), Aid Worker Security Report 2020, Humanitarian Outcomes, https://www.humanitarianoutcomes.org/sites/default/files/publications/awsr2020_0.pdf, accessed on 21 August 2020.

Stoddard A. (2003), ‘Humanitarian NGOs: Challenges and Trends’, in Humanitarian Action and the ‘Global War on Terror’: A Review of Trends and Issues, Macrae J and Harmer A (eds.), HGP Report 14, London.

Van Brabant K. (2000), Operational security management in violent environments, Humanitarian Practice Network, London.

Wolff, A. T. (2018). Invitations to Intervene and the Legitimacy of EU and NATO Civilian and Military Operations. International Peacekeeping, 25(1), 52-78.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- NGOs and States in Global Politics: A Brief Review

- International NGOs: Legitimacy, Mandates and Strategic Innovation

- Opinion – Administrative Reparations for Victims of Conflict-Related Sexual Violence in Ukraine

- Opinion – The Unintended Consequences of Foreign Aid Bypass

- Opinion – How Global Politics Exploits Women’s Health

- Human Rights and Civilian Harm in Security Cooperation: A Framework of Analysis