Having disintegrated, the Soviet Union left the Central Asian region with its legacies of nuclear security threats, clustered society, economic decline, social discontent and weak governments. All these contributed to breed extremist opposition to the government with serious danger of turning into radicalism. This political resulted in thee U.S intervention in the hitherto unfamiliar region and strive for brokering social stability, secure nuclear weapons deployed by the former USSR and strengthen governments to fight extremism. Later on, the region became inevitably significant for U.S interests owing to September 11 attacks in 2001 and the subsequent war on terrorism. This paper deals with studying U.S policy in the light of threats posed to U.S security and hence its conceived goals to eliminate them. It examines the policies of all of the four administrations in the region since the USSR has withdrawn from the region.

The paper proposes that the U.S has failed to materialize its aspired goals in the region largely due to a common set of policies, characterized sadly by an exhibition of ‘Disinterest’, on part of all of the administrations since long. Those themes, deemed as the cause of U.S failure, have been identified in this paper and it is maintained that if at all Washington wants to succeed, it must mitigate those pitfalls. This paper starts by introducing the region: its historic and geographic importance, post-Soviet dynamics, moves on to enunciate U.S entry into the region and policies pursued since long, then it identifies the shortcomings in U.S policy and lastly concludes with providing some recommendations.

The paper covers US foreign policy from Clinton’s administration in 1990s to Trump’s administration in contemporary times. It only revolves round policy pursued in Central Asian region. The Central Question addressed in the paper is: What has caused U.S failure in Central Asia?

The study would prove to be instrumental in understanding U.S policy in the region and identify the pitfalls causing failure. It identifies the previously unidentified theme of continuity in its policies and may prove to be helpful in guiding U.S policy towards the right direction in order to enable it to counter the imminent challenges posed by internal and external factors (China and Russia) in the region. The hypothesis formed addresses the issue of U.S foreign policy failure in a new light: A set of common continued policies by all administrations exhibiting ‘disinterest in the region’ is the primary cause of U.S foreign policy failure in Central Asia.

Chapter ONE – About Central Asia

Region

Encompassing five former soviet republics, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Kyrgyzstan, the Central Asian region extends from the Caspian Sea in the West to Western China in the East and from Russia in the North to Iran and Afghanistan to the South.

The geographic landscape of the region is divided into the grassy steppes of Kazakhstan (North) and the Aral Sea Drainage Basin (South). More than half of the region, about 60%, is desert land and the principal desert are the karakum which occupies most of Turkmenistan. The other desert is Kyzyl-Kum that covers most of Western Uzbekistan. Apart from this, the two river systems, Amu Darya and Syr Darya which drain into the Aral Sea through Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan after rising in the mountain regions in the East and South, provide for the water resources and agriculture of the region. On the South and East, the region is bounded by Western Altai and other mountain regions extending into Afghanistan, Iran and Western China.

The climatic conditions of the region are very dry reason for which the region is highly dependent on Amu Darya and Syr Darya for irrigation. Moreover, the paucity of water has led to uneven distribution of population with most people living along the fertile banks of rivers in the southeast while few people live in the vast arid expanses of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

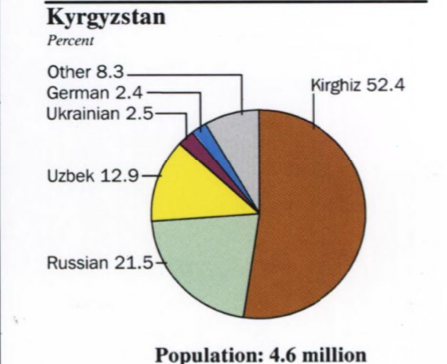

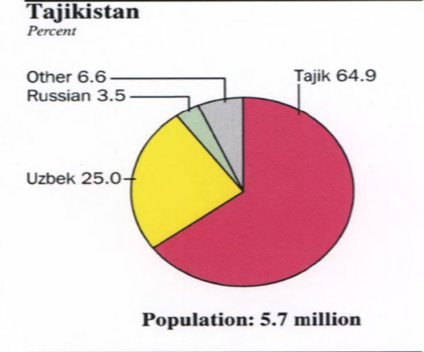

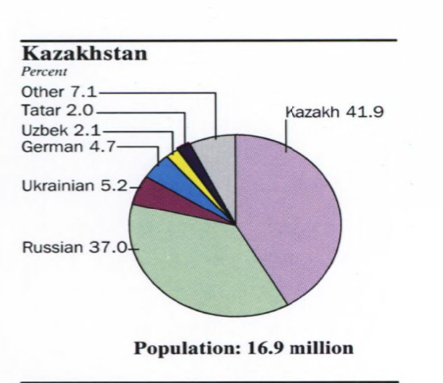

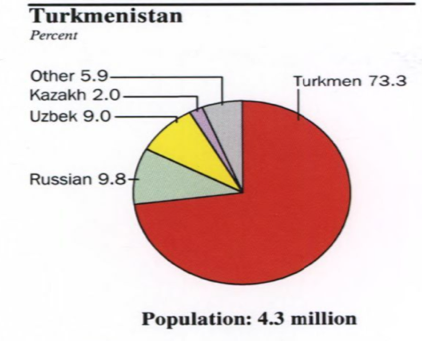

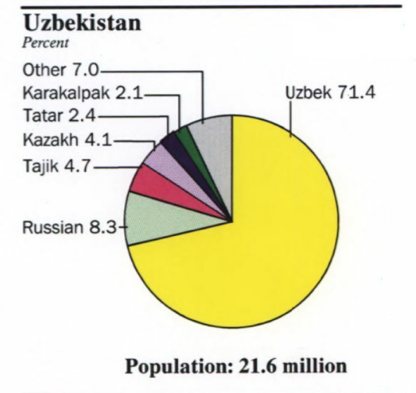

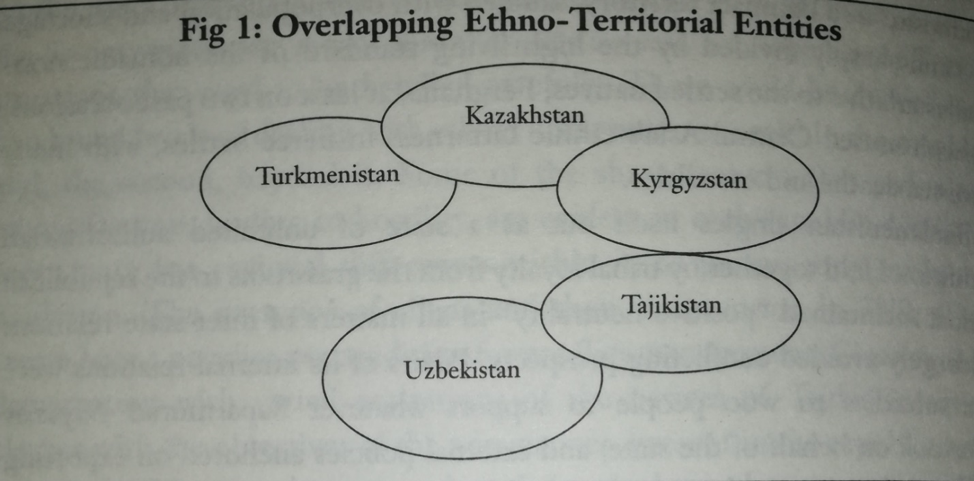

The five major ethnic groups of Central Asia are Uzbek, Kazakh, Tajik, Turkmen and Kyrgyz. This ethnic distribution has been an irritant into the regional unity subject to various historical instances and global context. The historical incorporation of the region into thee Soviet Union and arbitrary demarcation of state boundaries led to territorial disputes between Central Asian Republics after the Soviet disintegration in 1991. The republics claimed their stakes into each other’s territory after the soviet masters left, this is why Uzbekistan is referred to as the ‘Alpha-Stan’ of Central Asia, being the largest ethnic group having presence into every Central Asian republic.[1]

The economy of central Asia centers on irrigation, heavy and light industry, and mining. However, it is a faltering one. The resource rich republics lack the technological sophistication to exploit and utilize the resources, therefore they have plenty unearthed resources but meagre resources available that have been extracted. Moreover, the authoritarian and centrally planned economies are poorly structured with uneven reliance on few sectors; low FDI, drug trade, high debt-to service ratio and rising level of poverty are some indicators that flaunt the nature of the collapsed economies suffering from hyper-depression.[2]

The Bend of History and of Geography

The central Asian region has been an arch-important node throughout the course of history from serving as a transit route to a geo-strategic location as ‘pivot’ necessary to capture for global domination. The major attraction for dominating or capturing the region is thus economic i.e. vast resources of hydrocarbons, and geographic. Therefore, the predominant themes in its history are endurance of multiple waves of conquest; periods of isolation from global mainstream; and a high capacity to absorb new religions and ideologies.[3]

Catering to the first theme of conquests, the geo-strategic importance of the region has been enshrined by various scholars through their theories of geopolitics. Though the conquests have been laid down since the Samanid invasion in 9th century, much of the literature has impinged on modern history of conquests starting from the ‘Great Game’ between Britain and Russia in the 19th century.[4] The major influence on British naval power was that of Alfred Mahan’s theory of maritime realm to control Eurasia in order to maintain its hegemony. The land and continental realm were highlighted in Mackinder’s theory of heartland according to which “who rules the Heartland commands the world islands: who rules the world islands commands the world”. Spykman also centered his Rim land theory on the inner land of Eurasia in U.S geopolitics.[5] Given all of these theories, the steppes of central Asia are an important part of the Eurasian land that reveals the geo-strategic importance of the region. Accordingly, the Great Game of the nineteenth century for economic reasons, Cold War politics, post-Cold War Central Asia and the New Great game, again for economic benefits, can be expounded upon by these theories of the geopolitics, what Duarte refers to as a bend of History and Geography (from whom the subtitle has been borrowed).[6] The central argument is that it is a region of considerable significance in the prevailing economic arena as an outcome of its strategic location, as a link between East and West, an arena of competition and reinforcement of the Great power.

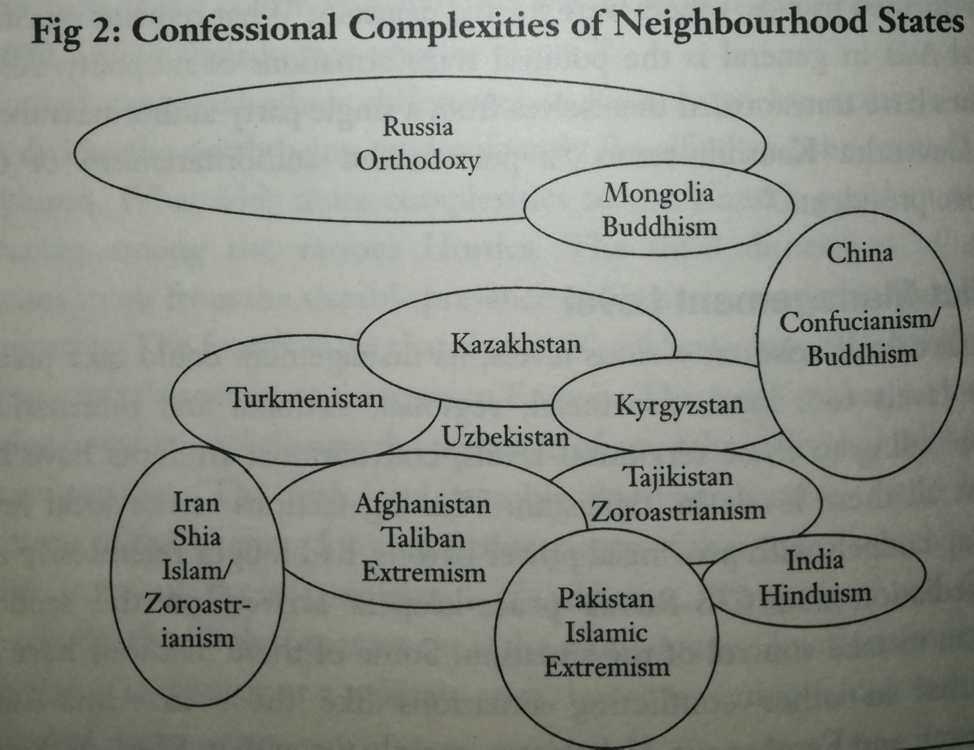

To provide a timeline of historical conquests, Central Asia was taken over samanids in 9th century which marked the birth of Islam in the region, since the homegrown religion there was Zoroastrianism followed by Buddhism, Christianity and Islam.[7] This was followed by Genghis Khan in thirteenth century and Timur in fourteenth century for the sole purpose of trade and city building, respectively. Russians entered the region in late 18th century in the wake of ‘Great Game’ under tsarist regime and since then have been infiltrating the region in various forms, phases and global contexts. Most importantly under Soviet Union of Bolsheviks when the region was turned into a single geographic whole known as Turkestan and later divided into 5 Stans arbitrarily.[8] Under soviets, the region served as first line of defense during the Cold War. The states were divided so as to perpetuate their dependency on the rulers and to rule out the possibility of any uprising. Their rule was highly centralized and authoritarian, restricting religion to mere ceremonial functions. After the disintegration of USSR in 1991, five independent states emerged based on the boundaries drawn by Soviet masters. Since then, the states in the region have been subject to external influence, predominantly that of Russia, U.S and China, and sometimes neglect.

Consequently, the aforementioned patterns of conquests have laid down the seeds of hybrid culture and ethnic mix, with the region demonstrating an amalgamated willingness to adopt new religions.[9] Throughout the history, religion has been moderately followed by the dwellers and ethnic harmony exhibited during authoritarian rule of Soviets. However, certain challenges have propped up in post-Soviet Central Asia regarding ethnic explosion and challenge of radical Islam coupled with intervention of U.S after 9/11.

Post-Soviet Central Asia

The disintegration of USSR in 1991 marked an earthquake change in the global political shifting world order in a unipolar system with the United States emerging as the sole superpower claiming the triumph of liberal world. This landmark shift had great many impacts on the Central Asian region, hitherto a united whole in the Soviet Union. USSR disintegrated into 15 states; Russia being the principle successor. The region saw the independence of five states based on boundaries divided during Soviet rule in 1924: Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan. Devendra Kaushik terms this as an ‘unintended independence’ largely as result of row between the metropolitan elite (Yeltsin vs. Gorbachev).[10] Notwithstanding, the CARs have trodden the path of developing their own political systems and policies although run by the same partocrats who served under previous masters. The president of each of the republics followed the same footprints of Soviets in that they consolidated authoritarianism, centralized the economy and curbed religious fervor.[11]

The new states faced challenges, some inherited from last rulers, at their outset. Among them, the most alarming were difficult economic situations, ethnic heterogeneity and religious radicalism. The tough economic situation owed much to the colonized economy by Soviets, as described earlier, coupled with meagre excavated resources. Moreover, some experts blame Soviets for deliberately blighting the economy of the CARs to perpetuate dependency and extract maximum benefits.[12] Moreover, the soviet legacy of mismanagement and demographic pressures keep haunting the economy to date. The other two challenges require a bit more inquiry, to be treated as separate topics, for they enunciate the post-Soviet politics of the region characterized by external infiltration i.e. U.S influence and Soviet counter influence until recently when the third actor, China, has started gaining ground and influencing the regional politics.

Ethnic Mix

With five major ethnic groups, Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Tajiks, Kyrgyz and Turkmens, the Central Asian region was delimited in Stalinist era arbitrarily. What was supposed to be carved out as ethno-national states turned into a hodge-podge of various ethnicities. This apparent discrepancy of national frontiers and regional spread of ethnicities did not pose a threat to authoritarian regime of USSR, however, it bred serious disputes between the newly independent states once they left the region.[13] The states demarcated were prone to major territorial disputes, some had already started to occur towards the end of soviet rule. Few instances include the clashes between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks in Uzgen and Osh region which left some 500 people dead, and civil war in Tajikistan by Uzbeks.

Two schools of thought describe this ethnic heterogeneity. Brzezinski sees this ethno-cultural and linguistic diversity within the CARs as ‘promoting instability’ prone to “external and internal conflicts”, while Cheryl Benard argues that it adds up to entanglement given that none of the ethnicity is clearly dominant. The argument goes that a culture with strong nomadic component is comfortable with a much higher degree of fluidity than a strictly sedentary society might be.[14]

The ethnic distribution and their complexities are represented in the figures ahead.

Source: United States. Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g7211e.ct000722/?r=0.775,0.503,0.285,0.114,0

Source: Central Asia: Present Challenges and Future Prospects (edited by Rao and Alam).

Religious Landscape

Islam, following the chain of religions from Zoroastrianism, has come to be the largely followed religion in the region. Central Asia’s history and cultural diversity has yielded a typical evolution of Islam, what can be termed as moderate and coexisting. The eclectic and flexible nature of Islam is due to the amalgamation of pre-Islamic values and traditions of the region. The Muslims of Central Asia are predominantly liberal Hanafi Sunnis and their practice involves various pre-Islamic traditions such as Ziyarat and Zoroastrian holidays; some even do not practice religion. Benard terms this as folk Islam that entails Sufism, practiced by Urban intellectuals, and lapsed Islam – occasional prayers and rituals.[15]

However, fearing the radical tendencies of Islam, the Soviets tried to stamp out the influence religion so as to debar any possibility of rebellion. This resulted in the policy of managing Islam where the influence and practice of religion was reduced to the observance of ceremonial functions and occasional rituals. This way Islam in Central Asia saw its lowest point in history under Soviet rule, from the high point of the 10th century.[16] Since the Soviets were succeeded by same partocrats that served them, so they carried on their legacy and embarked on the policy of managing Islam under the highly centralized authoritarian rule. This however also helped them to get away with immediate problems of political expediency, inter and intra-ethnic divide.

After the Soviets left the ground, the CARs were met with unintended problems of ruling the capriciously divided population, poor economy and territorial disputes. Amidst these, the major imbroglio that emerged was fading of central authority that had long since managed complex issues, the tight control over religion also lost its grip. Consequently, the mainstream Muslims got the freedom to express their religious sentiment and most importantly their displeasure. As put by Kaushik “the leadership in all five CARs is faced with the challenge of radical political Islam, albeit in varying degrees, largely as a result of growing frustration among the masses on account of their failure to effectively tackle the problems of poverty and economic development.”[17] The immediate manifestation of this was the establishment of Islamic renaissance party in 1990. The response to this increased Islamic activism by the newly independent states was two pronged: prohibition and repression of anything that seemed radical and bureaucratization of mainstream religious activities.[18] Under the couch of these policies, the Central Asian Republics centralized the religious ministries and board which held directly under them the powers of appointing the clergy, deciding school curriculum, registering the seminaries, supervising sermons, looking after religious publications, dismissing clerics etc. these countries have formulated hierarchical bodies under the ministry of justice under which various councils, committees and boards perform different jobs. Besides this, the registration or functioning of any religious party as a political party has been banned, except Tajikistan which ceded to the pressures of Uzbek civil warriors and granted IRP the registration as official Islamic political party however it also dissociates itself from radicalism and downplays such trends in the country. The party has now been removed by president Imamali Rakhmanov in 2015.[19]

However, the historical bent towards moderation religion and tent surveillance of Islam could not prevent the outbreak of radical forces, of which the IRP laid foundation. Olcott and Babajanov describe this development by arguing that the fall of the invincible Soviet state followed by economic disarray and social insecurity had convinced Muslim activists that moral turpitude had brought Soviets down. Therefore, it helped them muster their arguments and they organized their own party.[20] Two religious organizations have come to represent radical Islamism lately: Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) and Hizb-ut-Tahrir (HuT).

When the then Uzbek President, Islam Karimov clamped down on IRP, some prominent leaders escaped and found Islamic IMU. With the stated objective to remove President Karimov, IMU vowed to establish an Islamic state in the country. In the wake of these objectives, it legitimized use of force for Jihad against Karimov and came to International attention after the 1999 bombing in Tashkent, followed by raids in Kyrgyz, parts of Ferghana valley.[21] The international threat of IMU seemed real enough for it had its bases in Afghanistan, but it quickly lost its appeal in Central Asian masses once it started to access Al-Qaeda for funding and gradually it drifted towards embracing the global agenda of its sponsors. Reportedly, the group agreed to set aside its Central Asian campaign and instead support the Taliban in fighting Northern Alliance[22] which led to the heavy-handed response by the Uzbekistan government and its subsequent down fall. A Neo-IMU insurgency is said to have been sprouted after a series of suicide attacks on Uzbekistan’s police in Bukhara and Tashkent in 2004. This group is considered to be a splinter of IMU and HuT, with new recruitment strategies: underground jamaats, foreign members, female recruits, ethnic elite, and new fighting tactics- suicide bombings, female bombings and shootings.[23]

The other radical organization, HuT, was founded in 1953 splitting from Muslim Brotherhood and later took roots in Central Asia. Considered to be a successor movement of IMU, the organization aims at establishing Islamic caliphate, however it differs from IMU in claiming non-violent means to pursue political ends,[24] but resorts to basic Islamic teachings to spread Islamism. This is the reason why it got public support in Central Asia and tolerance from UK to operate its office from there. The other factor that worked to its advantage is its multi-layered secret structure, which makes it difficult to identify and target its bases and operations. Many regional and terrorism experts highly doubt the non-violent stature of HuT[25] based on their cadre structure, which is characteristic of extremist organizations, and increasing rancor of their rhetoric.

Given the Afghan jihad against Soviets and subsequent takeover of Afghanistan by the Taliban, increasing Muslim resentment towards U.S after Gulf war and Afghan civil war, geographical proximity of CARs with Afghanistan, and resurgence of Russian influence in the region, the rise in radicalism in the region marked the inevitability to devote attention towards hitherto neglected but vital region of the world. The next chapter elucidates the U.S entry into the region and policies adopted by the different administrations.

CHAPTER TWO – United States foreign policy towards Central Asia

The disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991 left a power vacuum in the region leaving the Central Asian states on their own to combat the corruption, radicalism and Cold War legacies. The political realities of Cold War notably the nuclearization of the region and the emerging challenge of radical threat given the geographical proximity of the region with Afghanistan, where religio-political war had just ended, compelled the United states to engage in the region, hitherto unknown.

Generally, American policy in the region, as everywhere, is guided by the global nature of its Geo-politics and Geo-strategy. As mentioned earlier, the Central Asia region is met with geopolitical approach given its pivotal location in Eurasia. Therefore, U.S influence on Central Asian Republics is multi-factorial and multi-level- strategic, economic, political, military and ideological. For better understanding the geopolitical influence on the various fronts, the U.S policy can be divided into three phases.

Since 1991, U.S policy in Central Asia can be divided into three phases i.e. post-Cold War, post 9/11 and contemporary. During the first phase, The Beginning, U.S policy largely thrived on securing legacies of Soviets and preventing them from creating influence again, however, this was met with a half-hearted attention by U.S which did not see the region as suitable to U.S interests at large. Attacks on the world Trade Centre and pentagon on September 11, 2001, drastically shifted U.S policy from disentanglement to active engagement whereby the region was perceived as geographically inevitable in the global war on terror. During this phase, U.S policy was overshadowed by security interests and consequently took the shape of military engagement with the CARs. The Third phase of U.S policy has seen the growing importance of unearthed hydrocarbons and increasing stakes of China and Russia in the region, consequently the U.S policy in this phase would be based on countering the potential competitors and extract optimum interests.

Phase 1: The Beginning of U.S policy

In the 1990s, the region was unfamiliar to the United States since it remained in the close orbit of the Soviet Union, even after its disintegration, the region was not perceived as a specific object of U.S foreign policy. To this extent, the security of the region was largely ignored and initially the U.S tried to maintain its footprint through Turkey, but it was also limited for the U.S did not regard turkey as “an agent for U.S security interests”.[26] U.S unwillingness to intervene in the region was manifest by its decision to stay away from the Tajikistan civil war of 1995 and allow Russian influence. This was characterized by a “honeymoon” period of cold war politics between U.S and Russia whereby they shared the interest in nuclear-free status of Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Belarus, And by U.S acceptance of the fact that Russia had important national interest in Tajikistan and declared that Russian attempt was not a conscious attempt to recreate the empire.[27]

However, the growing influence of Russia in the region as a result of its doctrine of ‘Near Abroad’ coupled with the potential rise of Iranian and Chinese influence, and the rise of extremist Islamism in the later-half of 1990s convinced many strategists that American interests lie in counter-influencing the rise of other external actors in the region and maintaining its status as insulator. Former National Security Advisor of US, Zbigniew Brzezinski revived Geo-politics as conceived by Mackinder and Mahan to prop up Northern Atlantic Alliance to counter the socialist world during the Cold War. He promoted the idea of “Zone of Instability” encompassing Trans-Caucus and Central Asia in which the prudent chess player would manipulate the tribal, ethnic and religious differences to his advantage.[28] Consequently, President Bill Clinton embarked on the policy of containment of external actors in the region. The major principles of his policy are discussed below.

Bill Clinton’s policy towards Central Asia

As aforementioned, the U.S presence in the early years of 1990s was dormant due to the reasons stated above. However, the policy took turn in the later-half of the decade which can be summed up into three aspects: securing the legacy of soviet weapons of mass destruction, protecting and defending the newly won sovereignty and territorial integrity of independent states against the suspected neo-imperialism of Russia, and breaking the Russian monopoly over Central Asian pipeline and transit routes.[29] The manifestation of these policies was hinged upon establishing rule of law to combat crime, corruption and augmenting a stable environment for energy exports. Furthermore, it was also concerned with threats of terrorism, non-proliferation and regional cooperation to be able to mitigate a situation of regional instability.

The primary concern of Clinton’s administration, as stated above, was to secure the weapons of mass destruction deployed in the region during the Cold War. In this light, the policy focused on facilitating the transfer of those weapons mainly from Kazakhstan to Russia; American vice president Al-Gore thus signed a ‘Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR)’ agreement with Kazakhstan’s president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, in December 1993 for ‘safe and secure’ dismantling of the 104 SS-18 missiles and destruction of their silos.[30] Resultantly, all bombers, their air-launched cruise missiles and approximately 1040 nuclear warheads were removed from Kazakhstan by April 1995.

Since the resources that America could employ to strengthen the Central Asian Republics were, so they were to be their own instruments of advancement thus shaping the second tier of Clinton’s policy towards the region. The centerpiece of U.S regional policy thus became “Support for Central Asian Countries’ independence and sovereignty”.[31] The underlying motive was to break the dependency of CARs on Russia and prevent them from falling into Chinese orbit of influence. An additional challenge emerging out at that was the rise of Islamism which posed formidable threats to CARs security and U.S own security at large. Consequently, U.S launched several agreements with these countries to ward off the three challenges and strengthen the countries to be able fight against these. A list of such joint ventures is presented below:

1) December 1991: North Atlantic Cooperation Council – a forum for dialogue.[32]

2) Oct 1994, “Freedom Support Act” for economic assistance.[33]

3) Feb 1994, Charter of Democratic partnership between Kazakhstan and US.[34]

4) Oct 1995, MoU between American and Uzbek defense ministries.[35]

5) 1995, NATO’s Partnership for Peace Program (PFP) for defense purposes. Since the initiation of the program the central Asian republics have taken part in various events conducted by NATO.[36] Such as (a) Central Asian Battalion (CENTZABAT); (b) Cooperative Osprey Exercise in North California; (c) Parachute drop by the US 82nd Airborne Division.

6) 1999, Silk Road Strategy Act whereby the US laid foundation for multi-faceted economic assistance to Central Asian states.[37]

To mitigate the rise of Islamism, Taliban, Al-Qaeda and IMU, U.S policy and assistance programs also incorporated counter terrorism, preventing politico religious extremism, border control enhancement and counter drug trafficking measures. Such measures include:

- Sept 2000, US State Department included IMU into its list of foreign terrorist organizations.

- June 2001, US and Uzbekistan signed “Cooperative Threat Reduction Agreement”

As part of American policy to curtail Russian monopoly over Central Asian pipeline and transit routes, it acquired new priorities in the lasting years of the Clinton administration, tabulated in Talbott Doctrine[38]: the Caspian’s hydrocarbons and Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline which bypassed Russia and Iran. As a result of this doctrine, Central Asia and Caspian were declared as zones of “US vital interests” and were included in U.S’ CENTCOM sphere of responsibility in 1997. Through this U.S signaled that it was not going to accept the influence of any external actor in the region.

Despite the lofty rhetoric, Clinton’s administration viewed the region as a low priority for it was not considered as pivotal to US interests. This is why the success to achieve greater security, stability and good governance remained murky. However, the World Trade Centre and pentagon attacks increased the region’s importance owing to its geostrategic location and U.S policy yielded a considerable shift towards it consequently. The next section studies American policy, during G.W. Bush, under the light of these events which marked the second phase of US strategy towards Central Asia.

Phase 2: The Turn of Events

September 11, 2001 marked an earthquake change in global politics and nature of warfare in that it ushered the emergence of an abstract non-state enemy against the mightiest of the state at that time and the other world at large. This landmark incident in the international arena required extraordinary measures to cope with it and accordingly the Bush administration followed a different trajectory from its predecessors in central Asia catering to the need of time. Hitherto, the Bush administration was as disinterested in Central Asia as its predecessors were owing to their perception of the region’s utility for American greater interest. However, when realities intruded upon the administration after 9/11, the region attained central role in American policy due to its geostrategic proximity with Afghanistan.

Bush Administration’s Policy

It can safely be said that Bush’s policy towards central Asia was driven by highly securitized measures. Though it merely continued Clinton’s policies of democratization and economic assistance, but the incident of 9/11 demanded a break away from it and required military efforts to combat terrorism. The central Asian region in itself did not pose any imminent threat to American security due its history of moderate religion, however, it was its location that made the region inevitable for U.S. In fact, the incident of 9/11 itself did not affect the regional dynamics as much as the Global War on Terrorism did.[39]

As part of the counter-terrorism policy worldwide, U.S sought active military action characterized by deployment of its military bases in the region, this marked the watershed between Clinton and Bush administration. Consequently, the Central Asian states started the process of lending their military bases to the U.S, among them Uzbekistan seemed to be America’s favorite choice for regional stabilizer, but it carried with itself the germs of irritancy by Kazakhstan which competed with the former country for regional domination. Therefore, a balance between the two needed to be maintained.

Nevertheless, Uzbekistan attained the status of resolute supporter of ‘Operation Enduring Freedom’ and entered into a classified agreement with U.S in 2001 which stipulated that some form of American guarantees would be provided to Tashkent. In return, it offered its Khanabad airbase which became the strongest foothold of U.S in Central Asia.[40] The other two countries, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, followed suit after initial reluctance while Kazakhstan found itself stuck Russia, China vs U.S quagmire. It had to take into consideration the Russian and Chinese alarm, the latter had reportedly pressurized Kazakhstan to abstain from providing air bases to US. However, in 2002 it signed memorandum with America to provide emergency landing rights at Almaty airport but no permanent bases which enabled Uzbekistan to win US nearness and take lead as regional stabilizer.[41] Turkmenistan became the only country to observe neutrality and refrained from providing any air base or assistance to U.S.

The bush administration, unlike the previous administration, pursued the policy on the internal dimension of the region as well, hitherto neglected. It maintained that the strategic partnership between the United States and Central Asian states was not confined to the Operation Enduring Freedom only but would go on to ensure stability. In December 2001, the then U.S secretary of state Collin Powell said that, “The US interests in Central Asian region stretched beyond the current crisis in Afghanistan”.[42] US Deputy Secretary James Wolfowitz also reportedly said that, “By upgrading its military presence in central Asia, The US wishes to send a clear message to regional countries- especially to Uzbekistan- that it will not forget about them and that it has the capacity to come back and will come back in whenever needed”.[43] Consequently, U.S policy principle turned from Central Asian Countries’ support for independence and sovereignty to fight against terrorism, proliferation and drug trafficking.[44]

The very idea of prolonging American foothold in the region coupled with the quasi fulfillment of policy promises started to bring problems. China and especially Russia were irked by the growing U.S infiltration in the region and noted that American soldiers stationed in the region were three times more than that stationed during the height of Cold War,[45] therefore, they started to grow influence in the region as well. This was also helped by the dissatisfaction of Central Asian Republics, owing to meagre endeavors of Americans to ameliorate the political instability, which now started to resist.

U.S relations went on to follow the low trajectory in the second term of George Bush who now came with policy of regime change and democratization in the Central Asian region and all over the nations.[46] The later years of Bush’s first term already marked by souring up of ties with Uzbekistan as a result of US support of revolution in Georgia whereby Islam Karimov’s repeated efforts to renegotiate the terms of Khanabad air base failed. Uzbekistan then started to tilt towards Russia which culminated into a treaty in 2004 on strategic partnership allowing each other to use military facilities located on either side.[47] However, two incidents later on resulted into complete breakaway of U.S-Uzbekistan ties.

Two months after President Bush assumed the office for the second term, popular protests toppled the government of Kyrgyzstan’s president Akaev, who had established the most liberal government in Central Asia. Though the direct involvement of U.S was not evident or possible reality, but the role played by American NGOs cannot be ruled out which allude to the possible desire of US Administration for regime change. The Central Asian allies came to see this as evidence of US as an unreliable ally.

Another incident, Andijan crisis in May 2005, served as an irritant in US relations with the regional states. An armed group, which had staged a raid on local prison, which later turned into a massive crowd opposing the government, opened fire on the Uzbek military. U.S and Europe declared it as an unarmed protest and demanded for inquiry into the matter. Besides, the US ensured that the protesters who fled to Kyrgyzstan to escape bloodshed would not be returned to Uzbekistan. Raged at the American response, president Karimov demanded that U.S vacate its Khanabad airbase within 180 days. In response, U.S cancelled the payment of arears and left the base by November 2005.[48] This breakup had implications for both U.S and Uzbekistan. The latter was encouraged by Russia and China because of this response to U.S and entered into certain agreements with them while the former turned to Kazakhstan to make it as the linchpin of its regional policies, but it did not bear considerable fruits.

Some scholars have come to view this as U.S failure to have lost its key ally in the region. However, the Bush administration exhibited a mix of plausible and flawed policies. Having retained the bases in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, the Bush administration managed to ensure its presence in the region, but it was void of any region wide palpable approach for stability and security in Central Asia. The legacy was passed on to the new administration of Barack Obama in 2008 whose policies are studied below.

The Obama Administration’s Policy in Central Asia

Backdrop to the new administration was provided by the waning influence of America in the region indicated by the incidents mentioned above. The baggage of legacy also included the lingering war in Afghanistan with its complicating dimensions, resurgence of Russian influence together with rise of China and Iran’s influence and potential rise of Islamism in the region in the shape of neo-IMU and Al-Qaeda nexus. Together with this, the problems to be countered by the new administration in the region were threefold: mistrust of Central Asian states regarding US effort to establish democracy given the support provided by previous administrations to authoritarian regimes, Russia’s opposition to this democratization and skepticism about it as US’ deliberate attempt to have permanent foothold in the region and the prolongment of war in Afghanistan which necessitated its presence in the region.

The new administration’s policy thus took shift from the previous one in that it turned away from the policy of democratization to implementing intelligent power – a blend of hard and soft power – and thrived not on the combat action but on politico-economic methods characterized by diplomacy and cultural ties. Democratization, according to them, could not be fostered on any country without ripe conditions there for implementing democracy and the Central Asian region lagged far behind. However, in regard with the said policy, the predecessors left with certain power levers in the form of establishing different funds and branches and various information and cultural centers: 22 in Kazakhstan, 15 in Kyrgyzstan, 9 in Tajikistan, 5 in Turkmenistan and 1 in Uzbekistan.[49]

However, Obama had come with specific interest in the Asia-Pacific region, therefore, his foreign policy was largely Asia-Pacific centric with an interest to develop relations with China.[50] This meant that Central Asian region was no more than a strategic necessity for America. This was manifest in Obama administration’s decision to delay Bush’s policy of Greater Central Asia and its goals were divided into mid and long term to be implemented accordingly. It was considered only as a part of U.S strategic plans aimed at transforming whole Eurasia into its geo-economic base through the Caspian region, Central Asian, Middle East and South Asia. The idea was to build a sanitary cordon along the Russian and Chinese borders.[51]

To this end, the policy towards Central Asia was confused and unclear limited only to transit of military Cargo for NATO forces in Afghanistan since the region’s transit routes were inevitable to continue war. The main thrust of US policy towards the region was hinged upon strengthening cooperation between U.S-EU and Central Asia in energy industry and subsequent Americanization of Caspian and reorienting flows of oil and gas towards Europe.[52] A policy skewed towards external dimension of the region and directed towards dissuading Russian and Chinese influence.

American disinterest in the region was further exhibited by the turmoil in Kyrgyzstan in 2010. An event that required active attention and action by U.S was met with idleness in that it put the onus to maintain regional stability on Russia who happened to be the leader of collective security treaty organization (CSTO) and Kazakhstan, chairman of Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe.

In addition to the growing detachment, the announcement of withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan was to have drastic implications for U.S policy in the region given its geographic importance for continuing war and a possible dent in that after the withdrawal. The post 2014 era marks the third phase of American policy in the region whereby the Obama administration in its last years and new administration was to take over in 2016 and pursue its policy in certain regional context. The next section enunciates the policy of Trump administration provided by the legacy of that of Obama.

Phase 3: Post 2014-Russia in Ukraine and US troops withdrawal from Afghanistan

Two events in 2014, notably the start of U.S’ forces withdrawal from Afghanistan and Russian intervention in Ukraine dictated Obama’s policy towards the region in his concluding years. Characterized long by the continuation of policy tools of Bush and failure of Obama’s New Silk Road Strategy, the administration tried to embark on a slightly different path by creating the forum of C5+1 – five Central Asian states and America, with a view to develop a common vision and perception of Afghanistan and strike regional integration to facilitate US policy of Afghanistan post withdrawal. Four projects come under the umbrella of C5+1: counter terrorism under the auspices of US institute of peace, facilitating private sector buildup of internal Central Asian market, promoting low emission and advanced energy solutions and analyzing environmental risks under USAID.[53] However, given the little interaction of Central Asian states among themselves and with Afghanistan, realizing these policy goals are a far reality and difficult one.

Succeeding Obama, the new administration of Trump assumed power in 2016. The foundation for his administration’s policies towards the region was laid by the longstanding challenges of Russian and Chinese influence in the region, rise of extremism, war in Afghanistan and defunct platform of C5+1 to mitigate these imminent challenges.

Trump’s Policy towards Central Asia

The above stated stumbling blocks in US policy coupled with the avowed rhetoric of Trump’s election, America First – Making America Great Again, indicated increased disinterest in the region and no considerable shift in US policy towards it. Like previous administrations, Trump’s administration does not view Central Asian region as of critical interest to US. As Anna Gusarova argues that U.S policy has always been shaped by pragmatic interests, so Central Asia does not have much importance in US foreign policy.[54]

The broad contours of Trump’s policy for Central Asia can be identified as: continuation of long-standing policies due to continuation of career foreign service; push battle against Russian influence in the region; continued securitization of US policy; budget cuts and meagre economic assistance.

The continuation of longstanding policies owes much to the appointment strategy of Trump, especially in the initial years. No turnover of US ambassadors by the presidents imply that these career foreign service holders will continue to the end of their career yielding no change in the current policy outlook. Furthermore, the annual bilateral consultations between the United States and Central Asian governments – a holdover from at least the Bush administration – appear to be continuing, as will the C5+1 regional discussion platform between the United States and the five Central Asian countries. However, because of the delayed establishment of the format, until its last fifteen months in office, the C5+1 has not been institutionalized at the senior levels of government, circumventing it to operate at working level only.[55]

Like the previous governments, Trump also faces the grave challenge of increasing Russian influence in the region, along with the new emerging actor in the region – China. Sanchez maintains that Russia and China have various outlets through which they maintain their security and trade ties with the Central Asian states such as Shanghai Cooperation Organization, Eurasian Economic Council, Collective Security Treaty Organization, Common Wealth of Independent states and more recently China’s Belt and Road Initiative.[56] Not only this, they also have geography on their sides which makes the communication and transition more easy. On the other hand, US has a far less coordination with Central Asian Republics comparatively, the gap needs to be bridged. In this regard, the Trump administration devised another mechanism alongside C5+1 that is the Trade and Investment Framework agreement council. During their May meeting, President Trump offered Uzbek President Mirziyoyev to host said meetings. The utility of this framework will be explicable as it unravels with time, however, an American official indicated that it would not match Russian or Chinese number: “if it works, TIFA would be a good way to promote trade with Central Asia… it will never reach Chinese or Russian numbers… but it’s something.”[57] Besides this, the American president endeavored to promote the ties by holding meetings with the heads of Central Asian states but even that too are sporadic to induce warm bilateral ties.

The practical manifestation of Trumps Central Asian policy is long held securitization of policy. The appointment of James Mattis, known as Mad Dog or Chaos, as Defense secretary alludes that his administration’s priority would remain the lingering War in Afghanistan,[58] and for this he needed Central Asia. Furthermore, the rise in extremism in Central Asia evident from the recent bombings of Istanbul airport, St. Petersburg metro bombing and the Stockholm truck attack, which were committed by extremists having roots in central Asia. Consequently, U.S embarked on further securitization of its policy, with bouts of socio-economic reforms. A total of $6 million donated to Tajikistan, in order to shore up its borders, serves as a good example of this.

Economy has central place in Trump’s national and foreign policies as result of rhetoric of making America Great again in that it focused on cutting aid to foreign countries and utilizing it internally as much as possible. This was to have significant impact on the Central Asian states facing aid cuts ahead. The trade between U.S and the region has always remained miniscule with Kazakhstan being the biggest trading partner having skimpy trade turnovers of just 2 billion dollars.[59] A major area of economic transaction is the energy sector, most importantly the CASA-1000 project in which the U.S has invested about $15 million. Moreover, the focus has been the Trans-Caspian Gas pipeline which provides an alternate to Russia, China and Iran.

CHAPTER THREE – Assessing U.S policy: A case of miscalculated continuity

Cheryl Benard has expounded a general framework/ model of US presence in non-western, semi-democratic states, in that, it can yield two disjointed consequences: policy goals may require the American realpolitik to strengthen the local leadership to achieve goals while its policy goals, that travel together with it, may largely be compromised which can in turn generate national resistance and earn global criticism.[60] In central Asia, American involvement has resulted into a similar paradox. It has generated mixed results with strengthening the indigenous governments to consolidate the political system, at least, if not reform it while largely failing to fulfill its championed policy values of democratization, economic development and human rights. The main thrust (hypothesis) of this paper is to argue that America has failed to attain success in both its rhetorical (democratization, Human Rights) and political (curtailing extremism, countering Russia and china, economic development, etc.) goals because of ‘continuation ill-informed policies’ by all of the administrations discussed above.

The central proposition of the paper is that all the administrations since the disintegration of US have continued to follow a similar set of policies, although with slightly different manifestation, despite tectonic changes in the global politics. Unlike various scholars which have a range of specific causes for US underperformance, this paper argues a common theme of ‘Disinterest’ in the region and miscalculated policies by all administrations thereof, have resulted into an amalgam of factors leading to US failure.

The region had never been a venue of interest for US policy makers, a host of Clichés and prejudice played into their disinterest. The Stans were, still are to an extent, perceived as a group of former Soviet Union (now Russia) in its backyard that failed to adopt Washington’s idea of privatization and now trudge along with dysfunctional economies and authoritarian regimes. In addition, the civil society droops, characterized by religious extremism, looking for US assistance met with resistance among US population. However, shifting political realties in the global and regional context shrugged American indifference towards the region and made its involvement inevitable. Since then, the subsequent administrations have followed certain trajectories owing to various causes discussed in previous chapters at length. The prominent themes among them, manifesting the policy of stark disinterest and miscalculation common to all administrations, which the paper deems to be the causes leading to US failure are: overstated threat of religious extremism and challenge of radicalism, externally oriented policies, incoherence in the region wide and country-level policies, unnecessary securitization of policies and strengthening the repressive regimes that have long since plagued the society into unending plunders and chagrins.

Radical challenge of Islamic extremism, overstated?

The foremost cause of American infiltration in the region, alongside disintegration of USSR, was the burgeoning challenge of religious extremism or, to put it another way, expression of social discontent through religious platforms such IRP, IMU and HuT, brought by soviet withdrawal. Consequently, US embarked on policies to curtail this extremism that had the potential to turn into large scale radicalism against US. This perceived threat, however overstated, has been common among all administrations following that of Clinton’s to trump’s and has led to securitization of US policies ignoring socio-economic uplift.

The Radicalism centric policies can be termed as misinformed, since the region has never exhibited any tendency of sliding down to extremism even during the times when nearing Afghanistan was embroiled into religious civil war post-soviet withdrawal and boiling after 9/11. This can be defined by the historic extraordinary religious moderation owing to the hybrid culture of the region produced by history of conquests. Religion in politics hit its lowest point during soviet rule when it was restricted only to ceremonial functions, although this policy was inspired by the political expediency, but it resulted into social harmony that can still be accentuated in the region.

In the presence of such tolerant religio-political culture, to suggest that extremism posed an existential threat to the region and provided avenues for anti-US drive was slightly a hyperbole. Carried on from soviet legacy, central Asian states maintain well-designed bodies under the ministry of justice to supervise religious matters, in that, they serve as watchdogs over madrasah education and clerics. They have under them, the powers of appointing and dismissing clerics, deciding and reforming madrasah curriculum. Not only this, any religious organization is barred from official recognition as a registered political party in all of the central Asian countries. Even the society does not appreciate any religious party to be representative of their demands. Amidst all of this, to pursue ambitions securitized policies seem unreasonable and have backfired instead manifest in growing repression of society by authoritarian regimes.

As far as sprouting of IRP, IMU and Hut is concerned, they all had regional appeal and aspirations and in no case colluded with anti-US forces, Al-Qaeda and Taliban, as ascribes of Islam vs US ideology. They had emerged largely as a result of socio-economic discontents brought by the Soviets and repressive regimes in the aftermath of their disintegration. The Vacuum created by the collapse of Soviet central authority, which had hold clutches tight on Islam, was filled by the mainstream Muslims to express their resentment, however, they lost their ground after they tried to expand out of the region and were met with high handedness of the governments. As a classic example of rejecting extra regional appeal of organizations, IMU lost its appeal in central society when it started to embark on Al-Qaeda’s line of action and gave up its regional aspirations. Not only this, but the threat from HuT of Central Asia was also misperceived in that it was more about social conditions of young people rather than Islam and the ideological framework they espoused for their expression was the theme of economic justice.[61]

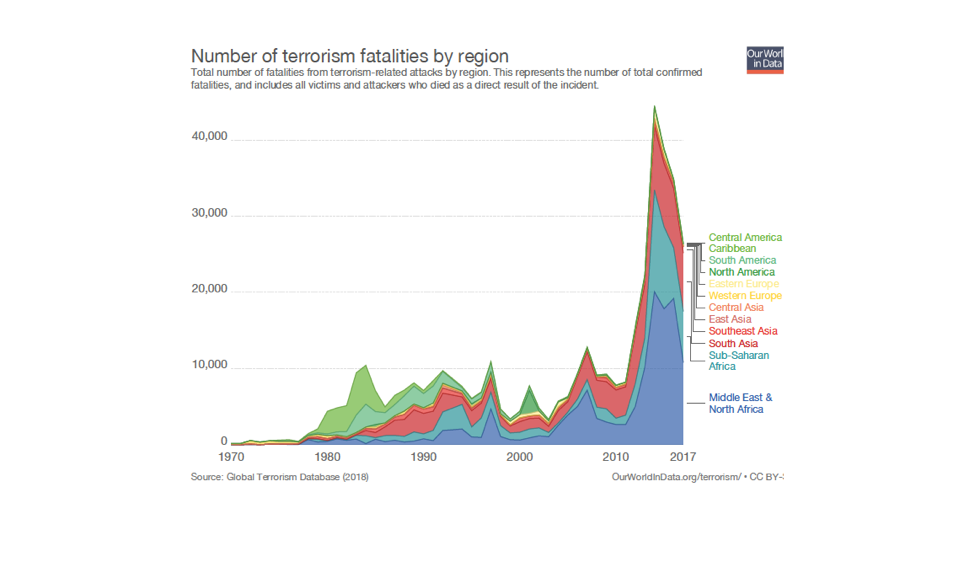

Moreover, these organizations had been disbanded by as early as 2005. Some smaller groups might have been functioning as splinters but not to an alarming extent so as to be counted as regional threats let alone global. Nevertheless, US continued to securitize their policies fearing a not coming extremism, even during the Trump era. A graph given on next page, indicating number of fatalities by region, shows the low level of threat emanating from the region.

Intervention in the region a function of External Events

American involvement in Central Asia remains fundamentally tied to interests outside the region,[62] says Catherine Putz. This implies that since the disintegration of USSR, US involvement in Central Asian region comes as a reaction of some happenings in the international arena or as a result of counter measures against other external actors’ influential measures in the region. This theme is evidently common among all the administrations studied above and has plagued the region with untold miseries as an outcome of its on and off mechanism.

Central Asia as a region, per se, had never been an area of interests for US policy makers due to the reasons already discussed, even its geopolitical significance did not intrigue Washington. Apparently, the impetus for US involvement was provided by Soviet withdrawal from the region and the threats looming large owing to security of nuclear weapons left by them, which was an external event. Since then, the mainstay of US policy, common in all administrations, towards the region has been to respond to the events happening in global context or as a result of extra-regional actor’s influence.

The major incidents in the international arena that have had considerable influence on US policy in the region have been the disintegration of USSR, 9/11 and global war on terrorism, and US troops withdrawal after 2014. In the first phase, the disintegration of USSR posed the threat of nuclear weapons thus attracting Clinton’s attention which had hitherto been dormant. The September attacks brought eventful changes in US attitude towards Central Asia which had now attained unprecedent importance, given its geo-strategic, for the successful execution of Operation Enduring Freedom, thus US entered into security agreements with the region and poured in dollars to earn support of ruling regimes. Likewise, the third phase of US policy in the region was also guided by developments outside the region: Russian invasion of Ukraine and US withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2014. Consequently, Obama in his later years and Trump’s administration afterwards pursued the policy of curbing Russian influence in the region through various platforms. Thus, the practice of taking diktats of extra-regional events and shaping policy in the region accordingly, has been commonplace in all subsequent administrations.

The other extra-regional determinant that informed US policies in the region has been the influence that extra-regional powers (Russia, China, Iran and Turkey) have enjoyed. Among them Russia has historically enjoyed considerable leverage. Since Soviet Union and afterwards, whereby the successor Central Asian Republics have always looked towards it with nostalgia of being a part of superpower at one time of international history . However, China has taken precedence in creating a strong influence in the region with its economic incentives manifest in Belt and Road initiative. Iran and Turkey have maintained a dampened presence in the region not capable of triggering US fears. In response to these growing influences in the region, the US has been compelled to maintain a presence in region that has often turned sporadic given it being unwanted. In that, it has tried to create counter-weight organizations and agreements to somewhat buffer others’ influence. The inclusion of Central Asian states into OSCE, NATO’s PFP programme, the idea of Great Central Asia, C5+1 and TIFA are but few instances of such attempts. However, having missed key opportunities, these efforts have not been instrumental in paralleling Russian or Chinese efforts, let alone neutralizing them. Stronski has gone on to say that China will have a greater influence in the region notwithstanding C5+1 and TIFA, and that “Central Asia [policy] is not going to get done until Russia is done, Afghanistan is done, and China is done.”[63]

A third factor that guides (rather distracts) US policy in the region is its commitment and engagement elsewhere in the world that keeps Central Asia from becoming a priority for US. Gulf War in 1990s, Afghanistan and South Asia post 9/11, and Middle East and North Korea in the current era have taken a larger share of US attention and dollars. Consequently, perceiving these as inevitable, Washington keeps a low presence in Central Asia and acquiesces to Russian and Chinese influence thereby.

All of these extra-regional determinants, affecting policies of all administration, taken together provide a formidable explanation to claim that Central Asia as a region in itself has never enjoyed US attention but is subject to various incidents occurring outside it that influence its regional dynamics and thus brings US in. Also, it presents a picture suggesting why US has not been able to materialize its interests and come out as a winner in the region.

Securitization of policies with inadequate spending

A general framework of US engagement outside its regional realm has been that of a military nature. Starting from proxy conflicts in the client states during the Cold War and then subsequent outside interventions after it: Gulf, Afghanistan, Iraq, Middle east etc. American nature of involvement is highly securitized. Such a theme has become quotidian in American foreign policy and is evident, in all administrations discussed, in the case of Central Asia as well.

Premised on the pretext of catering to the political necessity, the US has strengthened its stronghold of active military and security policies in the region. Following the disintegration of USSR, the US annexed Central Asian states into various security agreements and organizations listed in the previous chapter. The process of securitizing policies was catalyzed especially during bush administration when most of the money, channeled through US Defense department, was poured in to increase US military stakes. It was during his era that the US came to have a direct footing in the region having leased military bases from Central Asian states. However, having closed its bases around 2014-15 it still pursues securitized policies through different agencies and agreements. The C5+1 formula reached by the Obama administration envisages cooperation between US and Central Asian states in security realm more than in economic. In that, the parties agreed to cooperate in the following areas:

- Join hands as one region to address common security challenges and further mutually advantageous goals

- Bolster regional counterterrorism efforts and border security cooperation.

- Counter violent extremism in the region.

- Support the UN General Assembly Resolution recently adopted at Uzbekistan’s initiative to strengthen regional and international cooperation to ensure peace, stability and sustainable development in Central Asia.

- Explore ways to strengthen cooperation in promotion of stable, peaceful and economically prosperous Afghanistan

- Explore additional areas of cooperation such as border security and information sharing.[64]

This predominant theme is also evident in Trump’s policies through the continuation of C5+1 framework and his appointment strategies given in previous chapter. In fact, Trump administration’s policies are more securitized given its paranoia of Islamic extremism and rise in wave of militant attacks. Consequently, the already meagre economic aid has further been dwindled and exacerbated by the avowed foreign aid cuts by Trump.

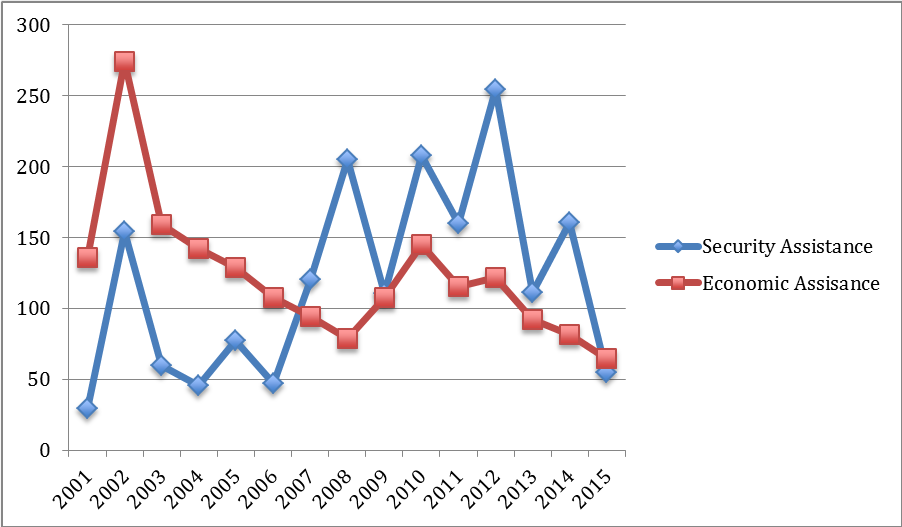

The security-oriented policies have largely come at the expense of economic development and uplift in the region. Abundant in mineral resources, the Central Asian regions have failed to capitalize on their resources, largely unearthed, and suffer from poorly structured and crunched economies breeding social discontent and deprivation. Worst still, the US has done too little to mitigate and integrate these economies into the global market. In all of the three phases of US policy, the nature of agreements sought is military with few economic implications, even its response to the economic arrangements of other actors such as SCO has been in military terms. Stronski puts it that the region has not been a major economic partner of US, with miniscule trade between them, and diplomatic engagement has been coopted by security leaving human rights frustrated, US Central Asia policy is securitized since 2001, thanks to its geographic proximity with Afghanistan and there is no sign that it will change during the Trump administration.[65] A graph representing US spending both military and economic is given below:

source: ponareurasia.com.

In the wake of these securitized policies, Trump has altered the channels (agencies) through which economic transaction is done with the region springing rifts with the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) which seeks to invest in humanitarian and economically beneficial areas. Moreover, the assistance routed through another principal agency: Assistance for Europe, Eurasia and Central Asia (AEECA), has been reduced to zero to be alternated with other channels of US defense department. Reportedly, Trump seeks to channel the assistance through the Economic support fund, which uses economic assistance to augment political and security goals of US foreign policy.[66]

Consequently, this nature of US spending has not helped society’s woes emanating from the social downturn. The indicators of social, human development, mortality, per capita income etc., to be highlighted in the next section, remain at appallingly low levels and are amongst the factors inflicting failure for the US to achieve its goals.

Support for Repressive regimes

The general model expounded by Cheryl Benard for US involvement outside its region, turn of international incidents, political necessity and securitized policies have all led to the strengthening of local regimes in Central Asian states. The role of these regimes can be defined by an operational paradox whereby they necessitate the support of the regime if the US wants to pursue its goals and on the other hand, they may be among the various causes responsible for US failure.

The society that was, long since the rule of USSR, rendered as socially and economically backward and instable was further blighted by the new rulers ‘partocrats’ after its disintegration, owing to the continuation of soviet legacy. This very reason, amidst the winding down of central authority, provided for the rise in extremism as an expression of society’s apprehensions. Much of the chagrins faced by Central Asian masses can be accentuated to the repressive, at times despotic, rule of these autocrats.

Having to engage in Central Asia, interacting with these rulers was indispensable for US presidents, however, this has not come without misuse and criticism. The US came to support the regimes when they had put the society on brink of falling apart as a result of their flawed and self-centric policies. Consequently, they consolidated their rule and curbed the opposition while pushing their masses to the lowest of social conditions. US support was often directed at the political opposers of the governments on the pretext of anti-extremist drive, this way politics became the business of these rulers marginalizing any dissent that might spread and US support without check served as a vindication for it.

Critics have enshrined the negative role US has played in strengthening these regimes. For instance, Rumer notes that: the war against radical movements waged by the US in neighboring Afghanistan has benefited and strengthened these regimes, for whom militant Islam had been a deadly challenge. The military footing of the US and economic assistance arrived just in time to prop up the faltering regimes.[67]

The rhetoric of policy values that the U.S claim to embark on while engaging outside: democratization, liberalization and human rights have been set aside. This was evident when the U.S facilitated a regime change in Kyrgyzstan which was most liberal out of all the Central Asian states at that time. Furthermore, the Obama administration had openly left the goal of pursuing democratization based on the alibi that the regional conditions were not ripe for such transition. In contemporary times, democratization and human rights seem to be out of Trump’s agenda as well.

In supporting the autocratic regimes Washington is itself inviting failure since these rulers do not attempt at ameliorating the deteriorated state-society relations by bolstering its economy and improve the living conditions – the primary cause of sprouting opposition prone to extremist expression. Support for the regime since years, if not altered, may lead to accentuate U.S policy as being misinformed and miscalculated. However, in course of future if the policy is redirected in the right direction, that is to say, not toppling the governments altogether at once but to incentivize them for opening up, pushing them to safeguard human rights and spending not in the hands of these despots but in societal education and uplift that may lead to ripening of conditions for application of democracy.

Impact of these continued themes

The war in Afghanistan has turned sporadic and protracted tiring U.S policy makers to continue with it, on top of it the abstract rhetoric of Islamic extremism has made it difficult to discern what has been made out about it, whether eradicated or not. In this Context, U.S policy in Central Asia, largely a function of U.S counter terrorism measures, has failed to attain significant benchmarks. Although, the United States has been able to prevent the society from falling apart by providing it the semblance of stability, however, it has failed in its efforts to democratize and liberalize the region failing to bring it in the fold of the global economic market. More importantly, the primary security reasons of infiltrating in the country have not been materialized as well, driving out the radical tendency (though limited to region, but is an avenue of exploitation), neutralizing anti-U.S dissent, helping Afghanistan war through creating interstate cooperation and curtailing the influence of Russia and China are goals yet to be achieved, aspired since long.

To be exact, the aforementioned set of common continued policies have, amidst little success, inflicted following challenges (failures) on U.S:

Successes:

- Establishing the essential sovereignty and territorial integrity of region’s states.

- Preventing the outbreak of fatal extremism in the region.

Failures:

- Failing to democratize Central Asian States and therefore attain greater legitimacy from society.

- Unable to prevent human rights abuse by the repressive regimes.

- It has not been able to create a credible leader of the region and make strong alliance with it.

- The economic development of region is in tatters, owing to policy failures in the region. It has not helped the region integrate in capitalist market, unearth resources and induce foreign investment.

- Washington has largely failed to drive extra-regional powers’ influence in the region out of, after a short-lived time span its own influence has declined providing Russia and China the space to increase their attacks.

- The regional frameworks designed by U.S such as GCA, C5+1 and TIFA have failed to achieve their outlined outcomes.

- America has also failed to enable the indigenous militaries of the regional states so that they can be able to mitigate immediate issues regarding security.

Conclusion

The geo-strategic centrality of Central Asian region has historically proven to be pivotal, be it as a historic route of invasions, a trade transit for ‘Great Game’ or part of heartland indispensable for controlling the world. Serving as a buffer zone for the Soviet Union the region was relevant and important in Cold War politics. The shift in world order after the end of the Cold War, with U.S emerging as sole superpower claiming its ultimate triumph of liberal world order, unleashed new facets that made it inevitable for it to engage in the part of the world hitherto aloof. The imminent dangers, inflicted by Soviet withdrawal, were of security nature and hence U.S intervened accordingly.

A comparative analysis of policies pursued by all the governments following the soviet integration reveals that they embarked on a similar set of policies for the reasons expunged in detail. Extrapolating these, the dominant theme of U.S adventure in the region is security and threat centric along with hedging against external rivals for power. However, yielding mixed results, largely unsatisfactory the actions taken bear the brunt of pushing the social fabric of Central Asian states to a reverse gear instead of uplifting it. The nature of U.S intervention has bred criticism against it not only in Central Asia but also worldwide. To mollify, it needs to depart from its current course of action and pursue new set of policies.

First, Washington needs to redefine extremism and reassess the radical challenge since most of the policies, even U.S entry into the region, emanate from the possibility of such a threat to U.S security and the need to curb. Instead of eradicating it, the policies have come as vindication for consolidating the repression of regimes on the flip side. More appalling, the state-controlled religion has defined the boundary beyond which any act may be perceived as extremist and is largely arbitrary, this provides the regimes leverage to come at loggerheads with their opposition and ultimately leads to the failure of U.S policies. A defined set of activities and ideology deemed as extremist may help U.S identify and defeat such elements.

Second, the overhauling securitized policies of U.S need to be changed and redirected at economic integration of the region with rest of the world in global market. Furthermore, improving the social indicators, providing employment opportunities and bringing foreign investment will help U.S create a strong support system in society and would convince them of Washington’s long-term strategy contrary to that inspired by short term strategic goals. Since long the policy of United states is misguided, in that, it aims to eradicate security concerns without addressing the root causes. The uprooting cause of burgeoning security threat is the social discontent brought by ill intended policies of local regimes, and U.S supporting them is seen as perpetrator siding with them.

Third, the falling influence of U.S and countering the rise of other extra-regional actors may only be helped through investing in meaningful terms. The ill-informed implementation of U.S policies has resulted into apprehensions against U.S and pushed the central Asian states in the sphere of influence of Russia and China. This sprouts out of different nature of investment by these actors; Russia and China’s framework of involvement hinges upon institutionalizing economic outfits through organizations such as SCO while U.S responds mainly in military terms through platforms such as C5+1, that too is insufficient proving to be unproductive. As already stated, the U.S needs to boost the economy of regional countries, invest in social sector- cultural exchange, education scholarships etc. and enhance indigenous capabilities of these states to convince of U.S long term interests. Moreover, democratization would be utmost instrumental in consolidating mutual, but this has to come through genuine training of society not through facilitating sudden regime changes for it has and will again backfire.

Lastly, a regional institutional framework, not any agreement or a dialogue, be devised so as to bridge the longstanding gap and provide effective interaction platform. All of the regional policies may be formulated and executed through this organization along with channeling economic assistance. This way, transparency would be ensured and the areas of investment lagging behind may be identified.

Conclusively, the reasons for U.S failure in Central Asian region and subsequently in its near abroad, especially Afghanistan, are both political and structural. If U.S is to succeed in its efforts these multipronged detriments must be dealt with. Or else, Washington may not be able to drive the lingering menaces out from the region and will continue to be paranoid by the ‘perceived’ security emanating from them.

Bibliography

Benard, C.(2004). Central Asia: “Apocalypse Soon or Eccentric Survival?”. In: A. M. Rabasa, ed. Muslim World after 9/11. Rand Corporation.

David Denoon, “The Strategic Significance of Central Asia”, The World Financial Review, 4 February 2016.

Cohen, Saul Bernard, (2015). “Geopolitics, Th Geography of International Relations”, ed.3. Rowman & Littlefield.

Daurte, Paulo. “Central Asia: The Bend of History and Geography”, SciELo, 2014.

Kaushik, D. (2003). The Post-Soviet Central Asian Republics. In: V. N. Rao, M. M. Alam, ed. Central Asia: Present Challenges And Future prospects.

Akbarzadeh, Shahram. Keeping Central Asia Stable, Third World Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 4 (2004), pp. 689-705, Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

United States. Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g7211e.ct000722/?r=0.775,0.503,0.285,0.114,0

Intel Brief: Islamic Extremism in Central Asia. http://thesoufancenter.org/intelbrief-islamist-extremism-central-asia/

Martha Brill Olcott and Bakhtyar Babajanov, “The Terrorists Notebooks,” Pakistan Defense Journal, April 2003.

Kai Hirschman, “Net Around German Islamic Fundamentalism Gets Tighter,” Deutsche Welle World, January 17, 2003.

Martha Olcott, Central Asia’s New States: Independence, Foreign Policy, and Regional Security (Washington, DC: US Institute of Peace Press, 1997), p. 172.

Evgeny F. Troitskiy (2007) US Policy in Central Asia and Regional Security, Global Society, 21:3, 415-428, DOI: 10.1080/13600820701417840.

Alam, M. M. US Policy in Central Asia Problems And Prospects. In: V. N. Rao, M. M. Alam, ed. Central Asia: Present Challenges And Future prospects.

Eugene Rumer, Richard Sokolsky, Paul Stronski. US policy in Central Asia 3.0. Carnegie Endowmnt For International Peace, January 25, 2016.

www,nato.int

Lamulin Murat, US Strategy And Policy in Central Asia, 2007.

Rao, V. N. (2003). Religious Extremism in Central Asia Towards a conceptualization. In: V. N. Rao, M. M. Alam, ed. Central Asia: Present Challenges And Future prospects.

Lamulin murat, US Central Asia Policy Under Barack Obama, 2010.

Wilder Alejandro Sanchez, Central Asia in 2018: What’s the Future of C5+1? Geopolitical Monitor, July11 2018.

Anna Gusarova, The USA and Central Asia: What Will be the Policy of D. Trump’s Administration? Central Asian Bureau for Analytical Reporting, 1 October 2017.

Stronski, Paul. Uncertain Continuity: Central Asia and the Trump Administration, Carnegie Endowment For International peace, George Washington University, July 27 2017.

C5+1 Fact Sheet: Central Asian- U.S. Forum to Enhance Regional Economic, Environmental and Security Cooperation, US Embassy Uzbekistan.

Catherine Putz, Will The US Ever Get A New Central Asia Policy? The Diplomat, May 3, 2017.

Boris Rumer, “The powers in Central Asia,” Survival, Vol. 44, No. 3, Autumn, 2002, p. 57.

[1] Benard, C. Central Asia: “Apocalypse Soon” or Eccentric survival?

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Denoon, The Strategic Significance of Central Asia.

[5] Cohen, S.B. Geopolitics; The geography of International relations.

[6] Daurte. Central Asia: The bends of history and geography.

[7] Benard, C. Central Asia: “Apocalypse Soon” or Eccentric survival?

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Kaushik, The post-Soviet central Asian republics.

[11] Benard, C. Central Asia: “Apocalypse Soon” or Eccentric survival?

[12] Ibid.

[13] Akbarzadeh, S. Keeping central Asia stable.

[14] Benard, C. Central Asia: “Apocalypse Soon” or Eccentric survival?

[15] Benard, C. Central Asia: “Apocalypse soon” or Eccentric Survival.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Kaushik, D. The post-soviet central Asian republics.

[18] Benard, C. Central Asia: “Apocalypse soon” or Eccentric Survival.

[19] http://thesoufancenter.org/intelbrief-islamist-extremism-central-asia/

[20] Olcott, M.B and Babajanov, B. “The Terrorist Notebooks”

[21] Akbarzadeh, S. Keeping central Asia stable.

[22] Benard, C. Central Asia: “Apocalypse soon” or Eccentric Survival.

[23] Ibid.

[24] ibid

[25] Hirschman, K. “Net Around German Islamic Fundamentalists Gets Tighter”

[26] Olcott, M. Central Asia’s New States: Independence, Foreign Policy, and Regional Security.

[27] Troitskiy, E, F. US policy in central Asia and regional security.

[28] Alam M. M. US Policy In Central Asia: Problems And Prospects.

[29] Rumer, E. Sokolsky, R. Stronski, P. U.S Policy Towards Central Asia 3.0.

[30] Alam M. M. US Policy In Central Asia: Problems And Prospects.

[31] Troitskiy, E, F. US policy in central Asia and regional security.

[32] www.nato.int

[33] Alam M. M. US Policy In Central Asia: Problems And Prospects.

[34] Troitskiy, E. F. US policy in central Asia and regional security.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Alam M. M. US Policy In Central Asia: Problems And Prospects.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Murat, L. US policy and strategy in Central Asia.

[39] Benard, C. Central Asia: An “Apocalypse soon” or Eccentric Survival.

[40] Troitskiy, E. F. US policy in central Asia and regional security.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Rao, V. N. Religious Extremisn in Central Asia Towards a conceptualization.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Troitskiy, E. F. US policy in central Asia and regional security.