This interview is part of a series of interviews with academics and practitioners at an early stage of their career. The interviews discuss current research and projects, as well as advice for other early career scholars.

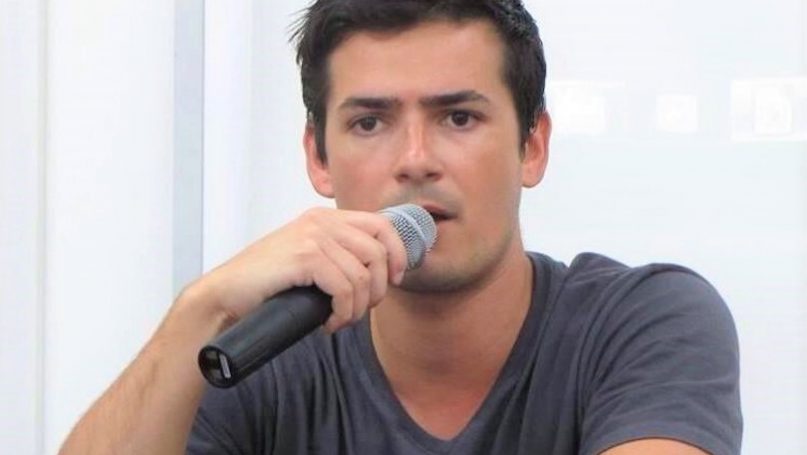

Miguel Dhenin is a post-doctoral candidate currently working at the Geography Department of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Brazil. He holds a BA in Political Science (UVSQ), an MSc in Strategic Studies (UFF) and a PhD in Political Science (UFF). He taught in the International Relations program of the Federal University of Amapá (UNIFAP). Miguel is a former junior researcher at the Institut des Hautes Etudes de l’Amérique Latine (IHEAL) in the Center de Documentation des Amériques (CREDA), Paris III Sorbonne-Nouvelle, France. He is a member of the RETIS Laboratory, part of the Geoscience Institute (IGeo), at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. He acts as reviewer for several IR journals and his research interests are mainly in borderlands, strategic studies, defense and the Latin American military affairs.

What (or who) prompted the most significant shifts in your thinking or encouraged you to pursue your area of research?

I think that my former MSc supervisor, Dr. João Carlos Albano do Amarante, made me realize during my dissertation, that studying the Brazilian military presence in the borderlands from a foreign and civil perspective was a great opportunity to understand the shifts in the Brazilian state since the democratization process. The Amazon region and borderlands represented a marginal area for both political and social sciences in the country. Nowadays, several graduate programs dedicate their courses (MSc and PhD) to these specific issues (borderlands, frontier, strategic studies, etc.). It’s no surprise to me because there are a lot of key strategic issues that need academic and scientific attention.

What is the military’s role in securing Brazil’s energy sector and the provision of public services? How have Brazilian armed forces secured the Amazon region?

Regarding Brazil’s energy sector, I think the military operate as a complementary tool to help improve engineering projects (roads, dams, plants) led by the federal government. It’s not unexpected, but part of a strategic plan for the Brazilian military toward the broad population (particularly in the Amazon region). For the Brazilian military, the main goal is to regain some of the trust and a more positive perception of the general population, particularly after the harsh dictatorship (1964-1985) that split the country. Just after the end of the military regime, the top Brazilian generals decided to step back from political affairs. The creation of the Ministry of Defense in 1999 was a decisive moment during the transition period. This distancing behavior continued and improved during Lula’s era.

Recently, particularly after the 2018 presidential election, the Brazilian military, led by the Army, kept an eye on Brazil’s internal affairs. Several political and corruption scandals took place during the last government of Dilma Rousseff and some conservative generals from the reserve publicly criticized Rousseff and helped to pressure her impeachment process. During Bolsonaro’s presidency, the military took a central role in Brasília. For example, seven of the 22 ministers have a military background. I think that the Covid-19 crisis was also a crucial moment as the Brazilian military responded by both helping the population in rural areas and strategically putting former generals in key positions in the presidential inner-circle.

It’s hard to state that the Brazilian Armed Forces ever secured the Amazon region. Due to its continental dimensions and diverse ecosystems, the region is a significant problem by itself. Despite this, since the 80’s, the federal government gradually improved its presence in the region, particularly in the borderlands by building special border platoons. But during the last decade, the SISFRON (Sistema Integrado de Monitoramento das Fronteiras) program shifted priorities to focus on a technological wall (with radars, wireless technology, etc.) to control the 16,000 kilometers of dry borderlands. The main issue here is its overall cost. For this reason, SISFRON started in the central ark of the border, mainly between Paraguay and Brazil. The program is still under a preliminary test phase and the Covid-19 crisis is not going to accelerate the process. It’s clear for both military and government officials that the Amazon region is not going to be prioritized. Instead, a lot of efforts are being directed to the Paraguay border.

What is the role of the Brazilian Army in the Acre and Roraima border strip in northern Brazil?

I think that the Brazilian Army operates as a dual player in these areas. On one hand, they help local populations regarding security issues, but also as a “friendly hand”, that embraces a social mission, when local states cannot afford to spend resources. It’s a great opportunity to create a deep sense of trust with the population, especially in the most remote areas. But lately the military was involved in some scandals, which could result in a backlash. For instance, during a presidential tour last year, a Brazilian Air Force sergeant flying in a government aircraft was busted transporting 39 kilos of cocaine, for the Spanish market. The official has since been charged with international drug-trafficking.

In Brazil, the term “Strategic Environment” is often used in National Defense and Strategy documents in reference to the strategic area of the South Atlantic Sea. What is your understanding of the term? Does Brazil have the capacity to handle this large area in the South Atlantic?

In my opinion, the ’Strategic Environment’ is a concept held to project Brazil’s role as a regional leader and potential global player. The concept was already used in the 70’s by the Brazilian geopolitical school, led by former general Golbery do Couto. Over the last decades, the concept was enlarged, from a geographical point of view. Now, the ‘Strategic Environment’ also embraces the Caribbean area, the West African coast and, Antarctica. So, the Strategic Environment as a concept is very large. The PROSUB program (Submarine Development Program or PROgrama de desenvolvimento de SUBmarinos) is a strategic program for the Brazilian Navy and a key element in handling the South Atlantic as a strategic area for Brazil. The project’s goal is to develop four conventional submarines (until 2022) and the first nuclear propulsion submarine is expected in 2029. This will give a strategic edge to navigating the South Atlantic area, also known as the ‘Blue Amazon’. Even facing an unprecedented political and economic crisis, Brazil has been able to maintain its strategic submarine program, but it will face some delays in the years to come. The partnership with France is also a very import element of the National Defense Strategy (NDS). Since 2008, Brazil and France agreed on bilateral military cooperation, especially regarding technological transfer for submarines (with the PROSUB program). France was supposed to sell 36 Rafale fighters but the deal was not closed. The Swedish manufacturer Saab finally won the contract and the Brazilian Air Force will be equipped with Gripen fighters.

The Brazilian government has close links to the military with key posts within Bolsonaro’s administration. What is your assessment of these links? How is security policy being addressed by this government?

The fact that the military occupies a central place within the Bolsonaro administration represents a turning point for Brazilian democracy. During the 80’s, the military gradually authorized a democratic transition, without completely leaving the political game. Now, democracy is under pressure, because the military is acting as a political piece, without the necessary safeguards that prevail in a democratic regime. Overall, security in Bolsonaro’s government is presented as an ideological totem that triggers anxiety in his electoral base. For instance, it’s common knowledge that his political base is formed by conservative Christian/evangelical white men, living in rural areas.

Security is seen as a key element in Bolsonaro’s rhetorical behavior. However, National Security Plans were also controversial (for example, Sergio Moro’s judiciary reform project has been publicly criticized by pundits) because reforming a complex system in a country such as Brazil is not an easy task. It demands a lot of patience and negotiation with the legislative and judiciary powers. Bolsonaro’s statements over the last few months clearly indicate a lack of political capacity and I’m not sure that there’s a real chance of a national initiative toward security that will gain parliamentary approval during this mandate.

What are you currently working on?

During my postdoctoral research project, I decided to work on environmental governance and border issues, especially in the northern area of the Amazon, the Guiana Plateau. I’ve been working as a lecturer for two years at the Federal University of Amapá, for the IR department. This experience shifted my research toward a broader agenda, providing a dialogue between military and environmental issues. The Covid-19 crisis affected my fieldwork but now I’m working on innovative approaches to deal with the current situation. Technology helped a lot to form some connections between my home university and counterparts in the Amazon region. Finally, the Brazilian government has been challenged recently by the international community regarding key environmental issues (deforestation, indigenous populations, wildfires, etc.). Thus, the sudden focus on environmental issues in the Amazon helped me and fellow researchers to promote our research projects, regarding the public and private sector.

What is the most important advice you could give to young scholars?

I think the most important advice for any young scholars in IR is passion. It’s the main factor that pushes you to study specifics topics or issues. The world is currently facing a huge challenge with the Covid-19 global crisis and we will foresee some demand for IR specialists worldwide. But now, we’re still in a delicate phase, so it’s maybe too soon to really see it. But passion and commitment to the field are, for me, very important elements to start a career in IR.