Children, along with the mentally ill and prisoners in countries like the United States, are the only category of citizens disallowed from having a say in their futures. That is to say, they are denied access to politics as a practice devoted by definition to making the future. But children are only the last of several such groups that had in the past been formally excluded from participation in political life. Not so long ago they had kept company with slaves, women, the poor, illiterate, colonised and religious or ethnic minorities of many kinds. And the reasons why children cannot be political actors remain the same as those that had prevented all these others from doing so. It is because they are not responsible for themselves that children cannot have a say in deciding both their future and that of others.

Such tautological arguments, once deployed against women, slaves and others, are still used to keep children out of political life. These include their congenital immaturity, ignorance, dependence on others, vulnerability to outside influence and inability to own or control the property. Yet children are also at the centre of politics insofar as it claims to make a future for them and even does so in their names. They also stand in for all the others who have been denied politics by reason of their racial, civilizational or gendered childishness. And in this way, they differ from prisoners or the mentally ill, whose temporary status is otherwise so similar to that of children without being conceptually central to political thought. Children pose a unique problem for politics since they cannot consent to make the very future they are meant to represent.

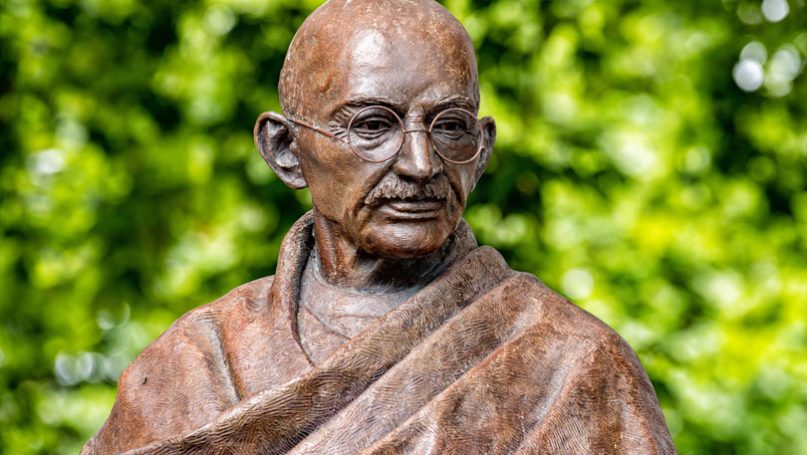

To my knowledge, M.K. Gandhi is the only modern thinker to have foregrounded the role of children in moral and as a consequence political life. And he did so precisely by attending to the child as a figure, much like the animal in this respect, which possesses no future in its own right. In his 1928 commentary on an ancient Sanskrit text called the Bhagavad-Gita, Gandhi argued that children and slaves represented ideal moral subjects. In doing so, of course, he overturned conventional notions of moral perfection, for which free and adult males were understood as subjects of this kind because of their independence, knowledge and serious investment in shaping the future. But for Gandhi, these very characteristics were what disqualified men from exercising moral and even political agency, while admirably suiting children for it.

It was precisely because children and slaves depended upon others, whether masters, parents or teachers, that they could and indeed had to live in the present without any thought of making the future. This allowed them to grasp the present with far more gravity than adults, for whom it was always being sacrificed for some vision of the future in acts of instrumental violence that were nevertheless unable to achieve their aim with any certainty. And even if the future is planned in this way did end up coming about, Gandhi thought that it could never escape the violence of its birth and, in addition, brought along with it any number of unforeseen consequences which gave rise to new problems and so invariably undermined the moral and political foundation it was intended to provide.

By pressing so assiduously to achieve only very specific ends, the violent instrumentality of politics was both idealistic and therefore eventually self-destructive. Children and slaves, however, by inhabiting the present more fully than others and giving their acts moral meaning in its terms, were unwilling to sacrifice the present for the future and instead able to do the reverse in prizing virtuous means over desired ends. And this meant that they left the future open to a number of possible ends, whose goodness was guaranteed by the very virtue of their means. This, Gandhi thought, was a far more realistic and even pragmatic way of behaving, one that made a place for the incalculable in political life if only so as not to be destroyed by it.

While he did not approve of slavery, of course, Gandhi paired slaves with children not only in a reference to their historical association but very deliberately in order to turn the traditional ideal of masculine independence on its head. His understanding of slavery as a form of experience leading to freedom also bears comparison to Hegel’s famous passage on the master-slave dialectic in the Phenomenology of Spirit. There, too, it was the slave’s labourious grappling with an obdurate world in the present that eventually allowed him to surpass what had become the master’s purely ideal domination of it. But where Hegel’s dialectic was nothing if not historical, seeking to push history into the future, for Gandhi the present remained the site of moral action overshadowing politics.

By focussing on the present in actions deprived of instrumentality, children and slaves were able to let the future emerge without trying to predetermine it in a violent idealism. And without this urge to make the future, violence exercised in the present would not be perpetuated in it. This made every moment of the future another present as if an instantiation of Bishop Berkeley’s theory about the non-existence of the external world in A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge. Yet in history made up of an innumerable series of presents, politics necessarily took second place to morality if it did not entirely wither away. Gandhi tied the future-making of politics to what he called modern civilization, by which he meant a world defined by the addiction to consumption that characterised industrial capitalism. And he seemed to think that it could be halted by social relations organised along other lines.

Let us take a closer look at Gandhi’s ideal child, whom he most frequently described in the mythological figure of Prahlad. The son of a demon king who unsuccessfully subjected him to a variety of tortures because of his virtue, Prahlad eventually brought about his father’s death by praying to Vishnu (Hindu lord) for deliverance. The king had received a boon which prevented him from being killed by man or beast, indoors or out, by day or night or by anyone born of a woman. One dusk, while boasting of his invulnerability to Prahlad, the king kicked one of the pillars of his palace walls daring Vishnu to appear. The pillar split open and out of it emerged Vishnu as half-man half-lion and proceeded to tear the demon apart. Why would Gandhi choose this graphically violent story of parricide as much as a deliverance to illustrate his ideal of childhood?

The story of Prahlad is one of sacrifice, but unlike biblical and other monotheistic narratives in which it is the child who must be sacrificed by a parent, as in the story of Abraham and Isaac, here the situation is reversed. This makes the child into the primary moral agent rather than a potential even if the consenting victim. Yet Prahlad doesn’t perform the sacrifice himself or take any part in it. All he does is endure his father’s torments and pray to Vishnu. In this way, he focusses entirely on virtuous deeds in the present and does not even consider the future that generally gives sacrifice its meaning. The fact that Vishnu appears at a moment of timelessness while occupying no particular place or species, sets aside all the regular coordinates of human action. And this plays into Gandhi’s vision of salvation as the incalculable element in moral and political life, one he often described as the incarnation of Vishnu on Earth. By removing moral action from the grip of the future and so the instrumental logic of means and ends, in other words, Gandhi opened the present up to a variety of unforeseeable possibilities. And in doing so he provided politics with many more options than the uncertain predictions of instrumentality ever could. Without eliminating the latter altogether, but rather subordinating if not overwhelming it with a proliferation of ends, Gandhi was able to link moral to political life in a way that did not insist on the purity either of one or the other. This certainly entailed taking risks, or being a gambler as Gandhi often described it, but such chances were not conceived of in the highly specialised terms that defines financial speculation. Instead it was children who best represented the relationship of moral to political life.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – What If Afghanistan Had Its Own Gandhi?

- Towards Advocating a ‘Tradition Approach’ to Gandhian Nuclear Ethics

- Gandhi and the Posthumanist Agenda: An Early Expression of Global IR

- Opinion – The Aam Aadmi Party’s Effect on Indian Politics

- Unmasking Forcible Displacement of Childhood: A Multidimensional Analysis of Ukrainian Children

- Opinion – Indian Politics in the Age of Neoliberalism