Gender gap in academia is a persistent global phenomenon as fewer women work as lecturers and professors than would be expected, given the relatively equal numbers of men and women as graduate students (Aiston & Fo, 2020). This is, in particular, a continuing challenge for international relations (IR), a subfield of political science, where male academics dominate the professional ladder and academic publication (Atchison, 2018). The literature on gender disparities in IR has increased significantly in the last couple of decades, especially literature based on Teaching, Research, and International Policy (TRIP) surveys of scholars in the United States (Maliniak & Tierney, 2009), Australia, New Zealand (Sharman & True, 2011) and twenty other countries, including some from Asia (Maliniak et al., 2012). Moreover, prior studies available on gender, journal authorship, and citation suggest discussions were dominated by the Global North setting (Key & Sumner, 2019; Williams et al., 2015), leaving a vacuum of research about how women fare in IR in non-Western countries.

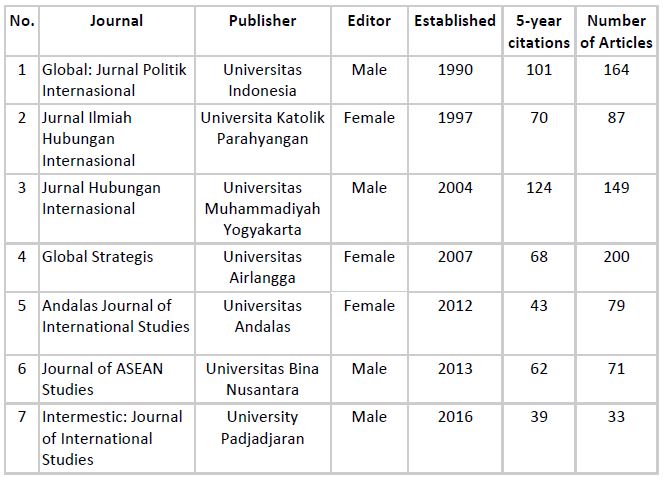

My research aims to fill this gap by incorporating the insights of quantitative and qualitative analysis using Indonesia as a case study. Findings from Indonesia offer excellent generalizability as they will expand the knowledge on how men and women differ in publishing IR scholarly works in Global South countries with similar education systems. Drawing on a bibliographic dataset, which consists of 783 published articles in seven of the most recognised Indonesian IR journals—listed in Higher Education’s (DIKTI) Science and Technology Index (Sinta) (Table 1), I have found that that the number of publications by solo women is significantly lower (31.42%) than those by solo men (48.40%). This result is rather predictable as almost 60% of IR lecturers in Indonesia are male. However, it is worth noting that the productivity gap is not as severe as in the US, where female authors comprise only 14% (in 1980–2007) and 19% of all published articles in the top 12 IR journals between 2004 and 2007 (Maliniak et al., 2008).

Table 1. List of Indonesian IR journals observed

Although IR departments have been established in more than 70 universities around the country, delivering study programmes for more than 20 years (Hadiwinata, 2009), academic publication only started to flourish in 2012. The clearest indication of this development is the emergence of new journals and the hike in published papers. This development is due to the encouragement policy that was taken by the central government. Since the mid-2000s, the Indonesian government, especially the Directorate General of Higher Education (DIKTI), has encouraged Indonesian academics to establish national academic journals as well as to publish academic works in national and international journals (see Law No. 14/2005 on Teachers and Lecturers and Law No. 12/2012 on Higher Education).

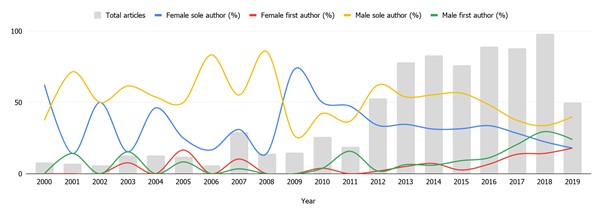

Figure 1. Productivity by gender among Indonesian IR academics, 2000–2019 (Source: Prihatini and Prajuli, 2020)

The global trend suggests men and women published in IR journals with notable gaps in productivity (Østby et al., 2013). The Indonesian experience offers empirical support to this assertion, except during the years between 2009 and 2011 (see Figure 1). Interestingly, in 2002, the percentage of men and women as single authors was equally distributed, whilst the collaborative paper was simply non-existent.

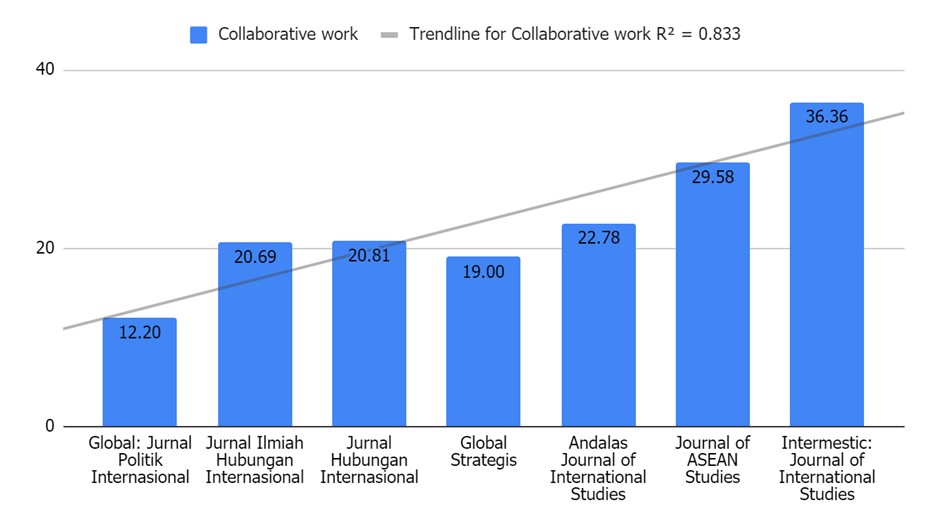

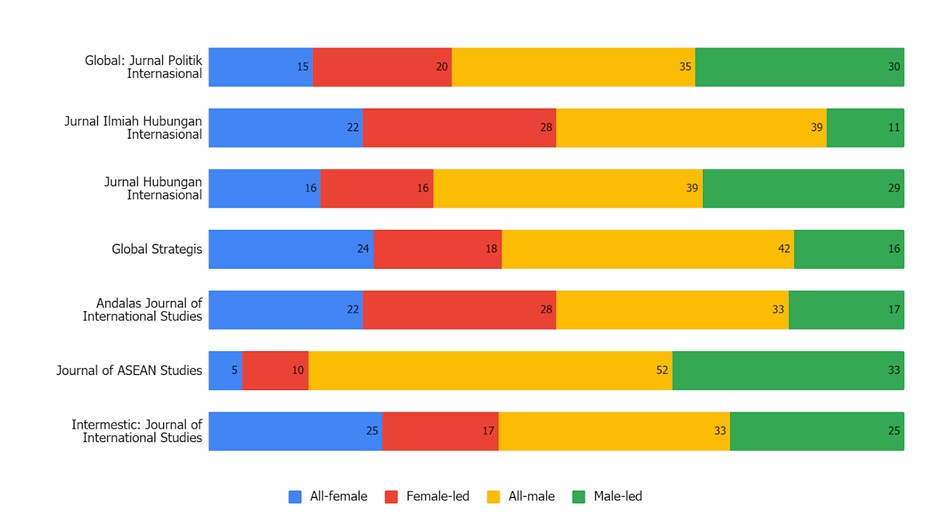

Scholarly publications in Indonesia, particularly in the field of IR, are currently at an infancy stage. Therefore, the enthusiasm to conduct research and to publish research findings is a fresh hope for the advancement of this field of science in the future. Nevertheless, the following graph suggests that the number of collaborative works remains relatively low. Only one out of seven journals observed has the composition of collaborative articles exceeding 30%, whilst the overall average sits at 23.06%.

Figure 2. Percentage of collaborative papers by journal

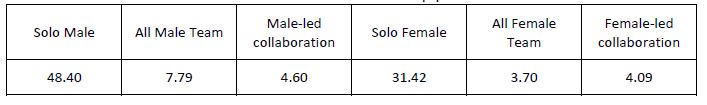

The data highlights the correlation between the age of the journal and the percentage of collaborative work (see Figure 2). Younger journals have published more collaborative papers than the older ones; for example, Global: Jurnal Politik Internasional, the oldest journal, has the lowest percentage of collaborative papers at 12.2%. Meanwhile, Intermestic: Journal of International Studies, which was established in 2016, has nearly 40%. Meanwhile, the overall authorship pattern (Table 2) indicates men tend to work and publish with other men, as the percentage of the all-male team is almost double that of the all-female team. This higher gender homophily among men limits women’s opportunities for leadership in scholarly publications.

Table 2. Gendered authorship pattern

In addition, as we look deeper into the patterns of collaboration in each journal, it is evident that men are more inclined to team-up with other men, as 33 to 52% of collaborative papers were published by male-only authors. In contrast, all-female teams range from as low as 5 to 25% (see Figure 3). Hence, the data suggests women’s leadership fare differently in IR journals, with the strongest shown in the Andalas Journal of International Studies and the weakest in the Journal of ASEAN Studies.

Figure 3. Distribution of collaborative papers by journal

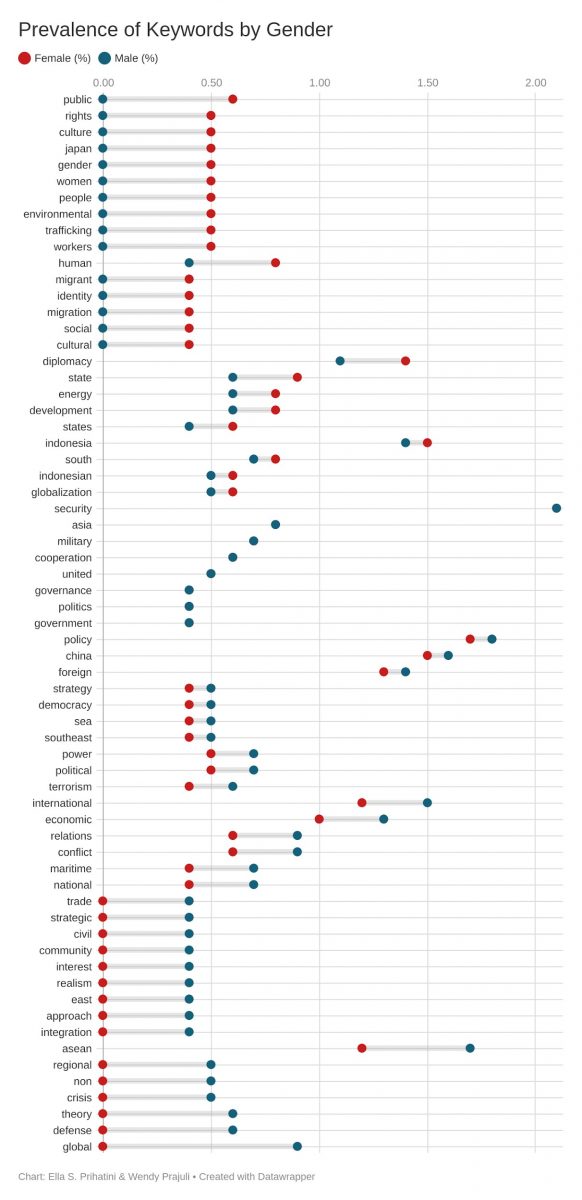

To further scrutinize the interest gap between men and women in their scientific writings, I analyse the words used as keywords from each paper published and plot the words with the point disparities as shown in Figure 5. The prevalence of keywords used by female authors is presented with red dots, while male authors are blue. Topics in which women are strongly dominating include ‘public’, ‘rights’, ‘culture’, ‘Japan’, ‘gender’, ‘women’, ‘people’, ‘environmental’, ‘trafficking’, and ‘workers’. The disparity between men and women in these subjects is 0.5 and 0.6%.

Also used more frequently by women authors, and yet with less disparity, are keywords such as ‘migrant’, ‘identity’, ‘migration’, ‘social’, and ‘cultural’. Meanwhile, male authors are by far more interested than females in writing on topics such as ‘global’, ‘defence’, ‘theory’, ‘crisis’, and ‘trade’, with the gap ranging from 0.4 up to 0.9%. Furthermore, although both genders shared interest in writing on ‘terrorism’, ‘democracy’, ‘strategy’, and ‘conflict’, the prevalence of men covering these issues is slightly higher (0.1–0.3%).

Figure 4. Prevalence of keywords by gender

One important takeaway from figure 5 is how men and women are covering some topics with the same level of prevalence. ‘Security’ comprises 2.1% of all keywords from both camps, suggesting men and women are equally passionate in exploring aspects relevant to security. This is in contrast with findings of other scholars which suggest men are more likely to write about security issues compared to women (Maliniak et.al, 2008). Likewise, the gender gap also does not exist for topics like ‘Asia’, ‘military’, ‘cooperation’, and ‘governance’.

Research on ‘security’, ‘military’, and ‘governance’ seems to be a shared interest between both sexes in Indonesia. Similarly, the frequency (in percentage) of male and female authors using the word “security” in the title is 1.3 and 1.1 respectively.

Therefore, I would argue that gendered preferences may not always be the best evidence to suggest that IR is a masculine discipline (Kadera, 2013; Tickner & Sjoberg, 2011), at least not according to the experience of Indonesian IR scholars. Women’s representation in “hard politics” topics is something that is worthy of attention as it signals their expertise as contribution to the conversation. Hence, more support is needed to nurture this participation if we wish to have a more inclusive IR field of study.

Some limitations to this study need to be acknowledged. One caveat is that the study focuses only on gender authorship in academic journals. Future research should consider analysing textbooks and IR curricula in Indonesia and other developing countries. It will also be interesting to observe the citation gap between male and female authors in the Global South setting. Despite the current limitations, this study contributes to an understanding of how gendered authorship takes place in a non-Western setting. More research is needed to unpack the connection between research and foreign policy. Does research influence foreign policy-making, or does it work the other way around, in which foreign policy dictates the themes, narratives, and scientific conversations?

References

Aiston, S. J., & Fo, C. K. (2020). The silence/ing of academic women. Gender and Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2020.1716955

Atchison, A. L. (2018). Towards the good profession: improving the status of women in political science. European Journal of Politics and Gender, 1(1-2), 279–298. https://doi.org/10.1332/251510818X15270068817914

Hadiwinata, B. S. (2009) ‘International relations in Indonesia: historical legacy, political intrusion, and commercialization’, International Relations of the Asia-Pacific. Oxford Academic, 9(1), pp. 55–81. doi: 10.1093/irap/lcn026.

Kadera, K. M. (2013). The Social Underpinnings of Women’s Worth in the Study of World Politics: Culture, Leader Emergence, and Coauthorship. International Studies Perspectives, 14(4), 463–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/insp.12028

Key, E. M., & Sumner, J. L. (2019). You Research Like a Girl: Gendered Research Agendas and Their Implications. PS: Political Science & Politics, 52(4), 663–668. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519000945.

Maliniak, D., Oakes, A., Peterson, S., & Tierney, M. J. (2008). Women in International Relations. Politics & Gender, 4(1), 122–144. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X08000068

Maliniak, D., Peterson, S., & Tierney, M. J. (2012). TRIP around the world: Teaching, research, and policy views of international relations faculty in 20 countries. The Institute for the Theory and Practice of International Relations, The College of William and Mary, VA.

Maliniak, D., & Tierney, M. J. (2009). The American school of IPE. Review of International Political Economy, 16(1), 6–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290802524042.

Østby, G., Strand, H., Nordås, R., & Gleditsch, N. P. (2013). Gender Gap or Gender Bias in Peace Research? Publication Patterns and Citation Rates for Journal of Peace Research, 1983–2008. International Studies Perspectives, 14(4), 493–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/insp.12025.

Sharman, J. C., & True, J. (2011). Anglo-American followers or Antipodean iconoclasts? The 2008 TRIP survey of international relations in Australia and New Zealand. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 65(2), 148–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2011.550100.

Tickner, J. A., & Sjoberg, L. (Eds.). (2011). Feminism and International Relations : Conversations about the Past, Present and Future. Routledge.

Williams, H., Bates, S., Jenkins, L., Luke, D., & Rogers, K. (2015). Gender and Journal Authorship: An Assessment of Articles Published by Women in Three Top British Political Science and International Relations Journals. European Political Science, 14(2), 116–130.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – It’s Time to Redefine Gender Mainstreaming

- Western Dominance in Indonesia’s Discipline of International Relations

- Gender Troubled? Three Simple Steps to Avoid Silencing Gender in IR

- Indonesia’s Role in International Relations: A Perspective from the Global South

- The Mandala, Agency and Norms in Indonesia-India Global Affairs

- The Geopolitical Influence of India And Indonesia in SAARC and ASEAN