China’s relations with Russia and the Central Asian states have steadily improved in the last three decades. With ideological tensions and border disputes being things of the past, the Moscow-Beijing relationship continues to develop dynamically through economic and trade cooperation, defense dialogues, and regional security cooperation. Many observers note that the current trajectory of Sino-Russian cooperation is reaching its limits and cannot be sustained in light of Russia’s economic turmoil in recent years and China’s growing presence in Russia’s backyard. It is argued that the growing asymmetry between China’s rise and Russia’s decline would inevitably result in tensions and increased rivalry, particularly in Central Asia. The Central Asian states, on the other hand, would be left at the mercy of great power politics. However, such analysis is based on two false assumptions: (1) the modern-day Sino-Russian partnership is primarily based on counterbalancing the hegemony of the United States; and (2) socio-economic and political developments in Central Asia should be understood through the lens of the Great Game narrative.

The complexity and multifaceted nature of the Sino-Russian strategic partnership should not be reduced to the “axis of convenience” argument, where the US is a common denominator. Likewise, the changing power dynamics in Central Asia between the two powers did not result in animosity or confrontation. Looking at the region through the Great Game narrative leaves very little agency to the Central Asian states over their future and oversimplifies the dynamics of the Sino-Russian relationship in the region. Instead, it will be argued that despite differences in regional approaches and overlapping interests, Russia and China are not locked in a traditional rivalry and do not compete for the same goals in Central Asia. The growing asymmetry between Russia and China in the region is accompanied by Moscow’s acceptance of its weakened position, China’s respect for Russia’s strategic interests, and shared responsibility for the security and stability of the region. Despite the Russian-Chinese duopoly, the Central Asian states retain a degree of independent decision-making in line with their national interests. Central Asia’s economic future lies primarily within its own neighborhood, and the resilience of Sino-Russian cooperation is in the interests of the Central Asian republics.

Background: Russia-China Relations

Western perceptions of the Russia-China partnership are often based on the trajectory of Sino-Soviet relations during the Cold War. China and Russia had close formal relations at the beginning of the Cold War, but by the 1960s, both sides saw each other as a competitor and a threat to their respective national security. As a result, Moscow and Beijing would remain antagonistic until the end of the Cold War. Framing the China-Russia relations through this lens has two shortcomings. One, it ignores major factors that led to the Sino-Soviet split, such as the China-Russia border in Manchuria and the ideological competition between the two powers over the leadership of the Communist world. Both factors are absent in the present-day Sino-Russian relations. The second factor is that it assumes that both nations have forgotten the massive costs and consequences of the Sino-Soviet split. The weakness within the critics’ appraisal of the current China-Russia relationship is that it bears little resemblance to the Sino-Soviet relations and has very different starting points.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War came as somewhat of a shock to both powers. It also meant that there was no other power to counterbalance the United States for both China and Russia. It was following the post-Cold War period that both Russia and China began to formulate the idea of a multipolar world order as an alternative to the unipolar global order dominated by the United States. Nevertheless, Russia and China were overwhelmingly concerned with their domestic economies as they both implemented economic reforms.

Despite warm relations between Russia and the US, it was during this period in the 1990s that Sino-Russian relations began to shape. Moscow and Beijing addressed some of the issues that led to the clashes of the Sino-Soviet split. Both countries signed an agreement on demarcation of the eastern part of their border in 1991, and a pact on the western border in 1994. The Manchuria border issue was formally resolved in 2004. It was also during this period that the foundations of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) were laid, as an attempt to manage the borders of China, Russia, and the other former Soviet Republics. Overall, relations between the two countries drastically improved, but the relations were still primarily predicated on the need for foreign stability to focus on the overwhelming attention paid to domestic reforms in both countries.

However, by the 2000s and onwards Russia and China started to become more strategically aligned. This was the result of American unilateralism under the Bush administration in dealing with the aftermath of the September 11th, 2001 attacks. This strategic cooperation only intensified as the United States became more actively engaged in East Asia, and began lobbying for NATO expansion into Georgia and Ukraine. The 2014 Ukrainian revolution and deteriorating relations with the EU finalized Russia’s pivot to Asia. It was during this time that Russia and China concluded an agreement, that was in negotiation for the better part of a decade, that would ship more Russian oil and natural gas into China. Furthermore, Russia agreed to sell China one of its most advanced air defense systems, the S-400 missiles, despite the various concerns about Chinese attempts to reverse engineer Russian military technologies. Overall, the current relations between the two countries have been at an “unprecedented level”, as Russian President Vladimir Putin concluded in 2019.

The increasing cooperation between Russia and China aims to be long-term even if there is limited historical precedence for it. This is also true of the increasing economic ties between China and Russia. Not only have trade between the two nations increased since the 2000s, but in recent years the two countries expanded their joint development cooperation. The best example is the development of the CRAIC CR929 commercial plane by China’s COMAC and Russia’s United Aircraft Cooperation. Likewise, within the realm of military technology, Russia is helping China to develop its nuclear early warning system. The flow of weapons has also become a two-way street. Russia is increasingly interested in purchasing warships from China, as they have been cut off from Europe. In their bilateral trade, Russia and China are gradually moving away from their use of the US dollar.

The current trajectory of the Russia-China partnership in many ways is aided by US sanctions on Russia and its trade war with China. However, it is not defined by it. The partnership between Russia and China has matured beyond the so-called “axis of convenience”. Russia’s turn to Asia was guided by the need “to develop Russia’s eastern territories, together with the complex sociopolitical processes of post-Soviet identity formation”. For Russia, it is also a symbol of its great power status in Eurasia. Today, the need to find an alternative to Western markets to help prop up economic activity is pushing Russia to look increasingly eastward and for China to look westward.

There are limitations to the Russia-China relations. Although their partnership is unlikely to deteriorate, it will not become an alliance. This is due to geographical constraints, as Russia is primarily a European power and China is primarily an East Asian power. Their primary concern is still within their immediate neighbourhood. Likewise, the military capabilities of both countries are primarily geared to the defense of their most immediate concern rather than to project power into the far reaches of the world. Chinese military capabilities may be formidable in deterring the United States in East Asia, but they lack the power projection capabilities to shift the balance of power in any meaningful way in Europe. With regards to Russia, outside of its nuclear capabilities, its ability to project power in the Far East is also limited.

Russia and China in Central Asia

On the surface, several factors may lead to a potential rivalry between the two powers in Central Asia: the weakened positions of the US in the region, Central Asia’s increasing economic dependence on China, Beijing’s rising military presence, and divergent approaches to regional order. These developments, however, did not result in hostility between the two nations. While questions remain about long-term prospects of the Sino-Russian relationship, the current trajectory of cooperation is far from being exhausted.

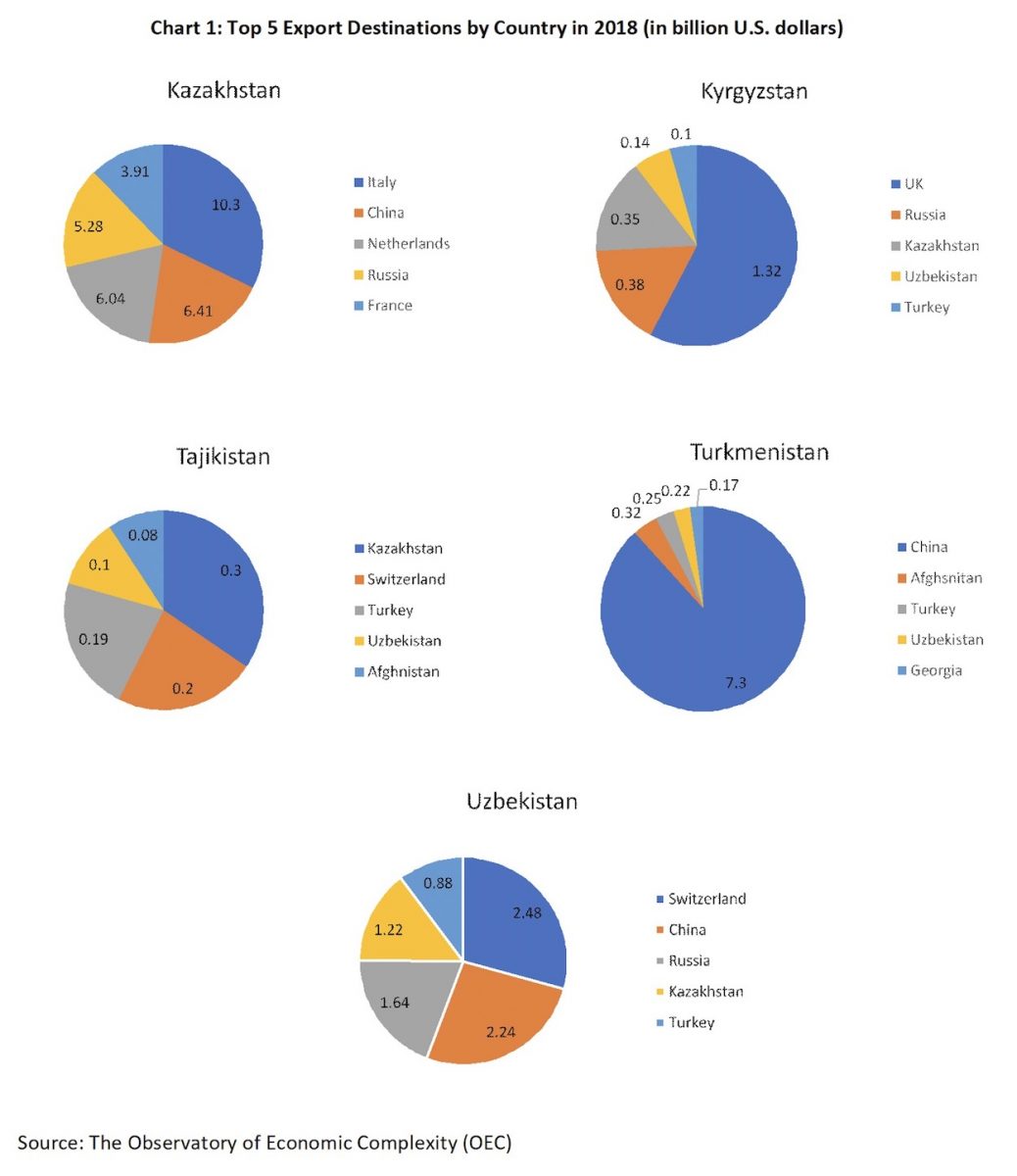

The growing asymmetry between Russia and China does not stem from direct competition for power and control in Central Asia. Rather, China gradually filled the void left by Russia. Much to the frustration of Moscow, its capacity to have a more solid economic footing in the region is limited. Russia’s trade with Central Asia accounted for 80 percent of the region’s trade in the 1990s. Since then, China was able to outpace Russia in many areas of trade, investment, and infrastructure development to become one of the most dominant actors in the region. Meanwhile, China is not the sole beneficiary of Russia’s decline. Other foreign governments and multinational corporations were also able to invest heavily in the region. Despite these developments, Moscow remains an important economic player for Central Asians. A closer look at the export structure of the key economic sectors of the five republics reveals that Russia has a lead in purchasing key commodities produced in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan at the comparative advantage while staying competitive with China in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

More importantly, Russia and China pursue different goals in the region. Russia often opts for a collective policy to consolidate its political power through the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). Meanwhile, China prefers to use a bilateral approach to secure its economic interests, energy security, and advance the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The context of BRI–EAEU coordination is very complex. It has been suggested that Russia is an ‘absent partner’ in the BRI, while the EAEU “appears to be the loser in this arrangement”. Although the EAEU is Russia’s own economic integration initiative, it is primarily used as a political tool. China also recognizes that Moscow plays an important role in the success of the BRI in Central Asia. While Russia’s cultural hegemony in the region is fading, it retains a strong influence over Central Asian political elites. It is especially relevant in the context of a growing Sinophobia and ethnonationalism in the region caused in part by China’s policies in Xinjiang. Given the circumstances, there is enough political will in Moscow and Beijing to harmonize their regional initiatives and avoid conflicts. In 2018, the two sides have signed an agreement on trade and economic cooperation between the EAEU and China. According to Arkady Dubnov, a Russian political analyst, “Russia was forced to recognize China’s leading role in financing and investment in Central Asia, and China promised to consider Russian interests in the region.”

In terms of hard power, for a very long time, China relied on Russian military presence in Central Asia and the SCO. China’s growing security role in Tajikistan and willingness to act outside of the SCO may pose uncomfortable questions for Russia. Many expect these developments to become a source of frustration to Moscow and a sign of China’s growing political ambitions. Yet, it may be too early to speak of a Chinese military presence in Central Asia. In terms of hard power, the available evidence suggests that China’s activity near the Tajik-Afghan border has more to do with Afghanistan than Central Asia. Beijing is concerned with the security of its western borders and the spread of terrorism and extremism to Xinjiang. In August 2016, the “Quadrilateral Cooperation and Coordination Mechanism in Counter-Terrorism” was formed by Afghanistan, China, Pakistan, and Tajikistan to strengthen the anti-terrorism cooperation among the four states. China also reached an agreement with Tajikistan in September 2016 to improve Tajikistan’s defense capabilities on the Tajik-Afghan border by constructing outposts and training centers. Given the current state of Sino-Russian military relations and persistent anti-Chinese sentiments in Tajikistan, it is unlikely that China’s decision to get involved was not coordinated with Dushanbe and Moscow.

The ‘Not-So-Great’ Game

The trajectory of Sino-Russian relations plays an important role in Central Asia’s economic development and security. It is also a factor in the successful implementation of the BRI, which sets to enhance regional cooperation and connectivity. By the same token, the five republics feel the pressure of their increased dependency on the Russian-Chinese duopoly, particularly their economic dependence on Beijing. This argument ties with the Great Game narrative, which focuses on great power rivalry in the region. However, the region’s dependence on Russia and China should not be overestimated. Several developments challenge the idea that Central Asian countries are passive pawns in this rivalry.

First, Russia and China are not the only players in Central Asia. Since the collapse of the USSR, other states were able to mark their presence in the region. For instance, Iran and Turkey, guided by economic opportunities, strategic interests, and strong cultural ties to Central Asia, are involved in their own competition for influence. Meanwhile, the EU continues to be one of the most important trade and investment partners for Central Asian countries. South Korea enjoys a good diplomatic and economic relationship with the region as well. Seoul seeks to continue investments in high-tech sectors of the region’s economy. Central Asia’s geo-strategic importance also attracts Pakistan and India, as both countries became full members of the SCO. These subregional dynamics give Central Asians states enough room to pursue independent foreign policy.

Second, Central Asia’s economic dependency on Beijing is often linked to large-scale borrowings from China to finance infrastructure projects. It is particularly true of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, which were left at high risk of debt distress. Yet, the China debt trap argument has been greatly exaggerated. Before COVID-19, both countries had been meeting their repayment obligations to China. Furthermore, Central Asia’s international trade includes many extra-regional partners, which often import more goods from Central Asia than Russia and China (Chart 1).

Finally, the rise of intraregional cooperation in Central Asia suggests that the five republics are in the process of solving their outstanding issues linked to border and energy disputes. Over the last three decades, Central Asian states have been pursuing a multivector foreign policy to increase their margins for maneuver. Regional cooperation among the five states will further help Central Asians to offset the effects of unequal power relations with Russia and China. Other regional and international actors are also interested in the further economic integration of the region. For Russia and China, a more unified region would make it more stable, secure, and predictable. It would allow for successful implementation of regional initiatives, such as the BRI. Central Asia also plays a key role in facilitating a peace dialogue in Afghanistan and its future economic development. In this multifaceted situation, it is in the interest of Russia and China to continue their partnership in Central Asia and not turn it into a battleground for influence.

Conclusion

The Sino-Russian relationship has come a long way over the last three decades. The two countries were able to solve most of their outstanding issues and begin strengthening bilateral ties. Much attention has been paid to the role of the US in bringing the two countries together. Today, however, the US is no longer the driving force in Sino-Russian relations. The uncertain state of American hegemony did not have a cooling effect on the Moscow-Beijing dialogue. Despite imbalances and asymmetries between Russia and China, their relations continue to develop dynamically. Not without limitations, this partnership is based on mutually beneficial political, military, and economic interests in an emerging multipolar structure of international relations.

Central Asia has become one of the key areas of China-Russia interaction. Despite a collision of interests, the governments of Moscow and Beijing are constantly renegotiating their positions in the region to avoid potential conflicts. An open rivalry may destabilize the region, which would run against their common interests. Central Asian states, on the other hand, are not mere spectators. The region hosts many regional and sub-regional arrangements that balance the Russian-Chinese duopoly. No regional actor is willing to upset this balance.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Russia’s Reaction to US-China Competition in Central Asia

- China’s Growing Role in Central Asia

- Central Asia: The Last Stronghold of a Declining Russia?

- Responses From Central Asian States to the Russian Invasion of Ukraine

- Evolution of Sino-Japanese Relations: Implications for Northeast Asia and Beyond

- The Geopolitical Implications of the Russo-Ukraine War for Central Asia