This is an excerpt from Crisis in Russian Studies? Nationalism (Imperialism), Racism and War by Taras Kuzio. Get your free download from E-International Relations.

There has always been Russian invasion, annexation, and military and other forms of aggression in what Oscar Jonsson and Robert Seely (2015) describe as ‘full spectrum conflict.’ There has never been a ‘civil war’ in Ukraine. Misplaced use of the term ‘civil war’ to describe the Russian-Ukrainian War is correlated with three factors. First, denial or downplaying of Russian military and other forms of involvement against Ukraine. Second, claims that Russian speakers are oppressed and threatened by Ukrainianisation with an additional claim that eastern Ukraine has a ‘shared civilization’ with Russia (Cohen 2019, 17). Third, highly exaggerated claims of regional divisions in Ukraine that point to the country as an ‘artificial’ construct.

This chapter is divided into four sections. The first section discusses terminology on civil wars and provides evidence from Ukrainian opinion polls that Ukrainians see what is taking place as a war with Russia, not a ‘civil war.’ The second section analyses how the Russian-Ukrainian War should be understood as taking place between Ukrainians, who hold a civic identity and patriotic attachment to Ukraine, and a small number of Ukrainians in regions such as the Donbas and their external Russian backers, whose primary allegiance is to the Russian World and the former USSR. An example of civic nationalism is Dnipropetrovsk in 2014–2015 when the region was led by two Jewish-Ukrainians (regional Governor Kolomoyskyy and Deputy Governor Hennadiy Korban) and an ethnic Russian (Deputy Governor and, since 2015, Mayor of the city of Dnipro Borys Filatov), who prevented Russian hybrid warfare from expanding west of Donetsk.The third section analyses the period, usually ignored by scholars, prior to 2014 when Russia provided training and support for separatists and violence during the Euromaidan Revolution, and the crucial period between 2012–2013 when Putin implemented policies as the ‘gatherer of Russian lands.’ The fourth section provides a detailed analysis of ‘full spectrum conflict’ that includes Russian intelligence activities, Russian nationalist (imperialist) mercenaries, Putin’s rhetoric providing signaling to Russian nationalists (imperialists), information warfare and cyber-attacks, Russian discourse on limited sovereignty, and Russian military invasion of Ukraine.

Theory, Terminology, and Why Ukrainians Do Not See a ‘Civil War’

Terminology is problematic in discussions about whether a ‘civil war’ is taking place in Ukraine. Tymofil Brik (2019) took Jesse Driscoll (2019) to task for ignoring the local context, neglecting census results and Ukrainian opinion polls and research (a typical problem found in academic orientalism), and being influenced by his experience working in Central Asia and the Caucasus, ‘which is not often applicable to Russian-Ukrainian relations, neither current nor historical.’ The Donbas War is not an ethnic conflict, unlike conflicts in Georgia and Azerbaijan, as Russian speakers are fighting in both Ukrainian security forces and Russian proxy forces.

A civil war is defined by Patrick M. Reagan (2000) and Nicholas Sambanis (2002, 218) as a war between organised groups within the same state leading to high intensity conflict and casualties of over 1,000 people, a definition which applies to the Donbas. James Fearon (2007) defines a civil war as a violent conflict within a country fought by organised groups that aim to take power at the centre or in a region, or to change government policies. A civil war challenges the sovereignty of an internationally recognised state, takes place within the boundaries of a recognised state, and involves rebels that are able to mount organised, armed opposition.

Sambanis (2002) analyses how grievances have transformed into mass violence. A violent rebellion would be likely if the state unleashed repression against minorities who hold political grievances. Ted Gurr (2000) has stressed the salience of ethno-cultural identities and their capacity to mobilise, the importance of levels of grievance, and the availability of opposition political activities. Scholars have also debated the causes of civil wars as either ‘greed’ or ‘grievance,’ which can arise from contestation over identity, religious, and ethnic factors. The World Bank’s Collier-Hoeffler model investigates the availability of finances, opportunity costs of rebellion, military advantage and terrain, ethnic and regional grievances of minorities dominated by majorities, the size of population, and the period of time since the last conflict (Wong 2006).

Sambanis (2002) argues that realism and neo-realism are unable to explain the outbreak, duration, and termination of civil wars because both sets of theories assume that the state is a unitary actor and cannot therefore explain why ethnic, religious, and class divisions emerge and threaten a state’s sovereignty. Neo-liberal theories, Sambanis (2002, 225) believes, are better equipped to explain the outbreak of civil wars and the role of non-state actors in fomenting them.

Constructivists believe that mobilisation of protestors is the work of elites (defined as ‘ethnic entrepreneurs’) who fashion beliefs, preferences, and identities in ways that socially construct and reinforce existing cleavages (Fearon and Laitin 2002). In the Ukrainian case, this argument would point to Manafort’s racist ‘Southern Strategy’ being used by the Party of Regions in the decade prior to 2014. An argument against defining the Donbas conflict as a ‘civil war’ is therefore the long-term work of Russian and Donbas ‘ethnic entrepreneurs’ during the decade prior to the 2014 crisis (Na terrritorii Donetskoy oblasty deystvovaly voyennye lagerya DNR s polnym vooruzheniyem s 2009 goda 2014). A constructivist approach has particular resonance in the Donbas, where oligarchs and the Party of Regions political machine dominated Ukraine’s only Russian-style managed democracy.

An important discussion of ‘civil war’ in Ukraine has been made by Sambanis, Stergios Skaperdas, and William Wohlforth (2017), who discuss how an external sponsor, in this case Russia, ‘can use different combinations of the different instruments at its disposal to induce rebellion and civil war.’ Russia’s intervention ‘activated’ cleavages and increased polarisation, ‘making it harder for the state to suppress the rebellion’ (Sambanis, Skaperdas and Wohlforth 2017, 13). As polarisation increased, inflamed by Russia’s information warfare and politicians’ rhetoric and outright disinformation, violence escalated. Without Russia’s intervention, anti-Maidan protestors in the Donbas would not have transformed into armed insurgents (Wilson 2015).

What is often ignored in discussions about whether what is taking place in the Donbas should be described as a ‘civil war’ is Ukrainian public opinion. Ploeg (2017, 177) dislikes the fact that only 13.6% of Ukrainians believe that there is a ‘civil war’ in their country and blames this on ‘anti-Russian’ media. Petro (2016, 198; 2018, 326) refuses to accept Ukrainian polling data, believing that they understate pro-Russian feelings, exaggerate anti-Russian attitudes, and downplay regional divisions.

Polls conducted in 2015 and 2018 found that between 16.3% and 13.4% of Ukrainians believed that a ‘civil war’ was taking place in Ukraine (Perspektyvy Ukrayinsko-Rosiyskykh Vidnosyn 2015; Viyna na Donbasi: Realii i Perspektyvy Vrehulyuvannya 2019). In a 2018 poll, the Donbas conflict was viewed as a ‘civil war’ by a low of 5.1% in western Ukraine and a high of 26.5% in eastern Ukraine. The number of those who believed in a ‘civil war’ in the east (26.5%) was lower than the 34.2% in eastern Ukraine, who viewed the conflict as a Russian-Ukrainian War (Viyna na Donbasi: Realii i Perspektyvy Vrehulyuvannya, 2019).

Furthermore, 72% of Ukrainians believe that there is a Russian-Ukrainian War, ranging from a high of 91% in the west to 47% in eastern and 62% in southern Ukraine. In Ukrainian-controlled Donbas, views are evenly split between 39%, who believe a Russian-Ukrainian War taking place, and 40% who do not (Poshuky Shlyakhiv Vidnovlennya Suverenitetu Ukrayiny Nad Okupovanym Donbasom: Stan Hromadskoyii Dumky Naperedodni Prezydentskykh Vyboriv 2019). Respectively, 76% and 47% of residents of Ukrainian-controlled Donetsk and Luhansk believe that Russia is a party to the conflict, with 12% and 31% respectively disagreeing (Public Opinion in Donbas a Year After Presidential Elections 2020).

Civic Ukrainian versus Russian World Loyalties

Arguments in favour of a ‘civil war’ fuelled by competing regional and national identities are only made possible by ignoring Russia’s long-standing chauvinistic attitudes towards Ukrainians, the many aspects of Russia’s ‘full spectrum conflict,’ and the intervention in Ukraine from February 2014 (Kudelia and Zyl, 2019, 807). Regional versus national identities provide a weak explanation for why protestors transformed into armed insurgents in the Donbas, but not in the other six oblasts of southeastern Ukraine. Transforming minority support for separatism in Donetsk (27.5%) and Luhansk (30.3%) was only possible because Russia provided far more resources in its ‘full spectrum conflict’ to these two regions. The Donbas had deprecated and denigrated Ukrainian majorities, while aggressive pro-Russian minorities were accustomed to undertaking violence against their opponents.

Some scholars emphasise the local roots of the crisis in the Donbas (Matveeva 2018; Kudelia 2017; Kudelia and Zyl 2019; Himka 2015). Tor Bukkvoll (2019, 299) attempts to have it both ways, confusingly describing the conflict as an ‘insurgency’ until August 2014 ‘even though Russian political agents and special forces most probably played an important role in its instigation.’ A regional versus national identities framework of the ‘civil war’ is at odds with the claim of an ‘absence of an ideology’ among pro-Russian forces in the Donbas (Kudelia and Zyl (2019, 815). This can only be undertaken by ignoring Putin’s belief of himself as the ‘gatherer of Russian lands’ implemented through Medvedchuk and Glazyev’s strategy (O komplekse mer po vovlecheniyu Ukrainy v evraziiskii integratsionyi protsess 2013) and Ukraine’s participation in the Russian World (Zygar 2016, 258).

Matveeva (2018, 2) is one of a small number of scholars who describes the conflict as one between civilisations, emphasising allegiance to the Russian World as ‘politicized identity.’ Scholars writing about identity in the Euromaidan have also talked about ‘civilisation choices’ (Lena Surzhko-Harned and Ekateryna Turkina 2018, 108). In contrast, ‘Ethnicity is a poor marker in Ukraine, and loyalty and identity are weakly correlated with it’ (Matveeva 2018, 25). From 2006, Putin began to talk of Russia as the centre of a Eurasian civilisation with superior values and distinct to the EU, which he portrayed as a harmful actor (Foxall 2018). This took place a year before the creation of the Russian World, three years before the launch of the EU’s Eastern Partnership, and four years before the creation of the CIS Customs Union. Attachment to civilisation identity (civic Ukrainian or Russian World), rather than language, is a better marker of loyalty in the Donbas War as there are Russian speakers fighting on both sides.

Nevertheless, Matveeva’s (2018) discussion of civilisation is confusing, as she wrongly defines it in civic terms as corresponding to Rossiyskie citizens of the Russian Federation. Tolz (2008a, 2008b) and other western scholars have long noted that civic identity is weak in the Russian Federation. The 1996 Russian-Belarusian union, a precursor to the Russian World, was a ‘challenge to the civic model of Russian nationality’ (Plokhy 2017, 319).

The Russian World is, in fact, a claim to the allegedly common Russkij ethno-cultural, religious, and historical identity of the three eastern Slavs. Russia is a ‘state-civilisation,’ and Putin is gathering ‘Russian’ lands that he believes are part of the Russian World. Taking their cue, leaders of the ‘Russian spring’ spoke of an ‘artificially divided Russian people’ (Matveeva 2018, 221). In both cases, they were saying that Ukraine is a ‘Russian land’ and that Ukrainians are a branch of the ‘All-Russian People.’ The Russian Orthodox Church concept of ‘Holy Rus’ supports the rehabilitation of Tsarist Russian nationality policy of a ‘All-Russian People’ with three branches. The Russian World and Russian identity are defined in ethno-cultural, not in civic terms (Plokhy 2017, 327–328, 331).

Kudelia (2017) believes that a clash over identities was fuelled by the influence of Ukrainian nationalism in the Euromaidan, which allowed Russian authorities to paint it as a ‘nationalist putsch.’ A more insightful way is presented by Matveeva (2018) who discusses a ‘civilisational’ divide between Ukrainians in the Donbas, who were oriented to the Russian World, and Ukrainians whose civic allegiance was to Ukraine (Kuzio 2018, 540).

This civilisation divide is perhaps what Dominique Arel (2018, 188) refers to when he writes of the ‘rebellion of Russians’ (that is, those living in the Donbas who thought of themselves as part of the ‘All-Russian People’). Arel (2018) alludes to an understanding of ‘Russian’ (i.e. All-Russian People’) identity as encompassing the three eastern Slavs. This also shows that those in the Donbas who viewed themselves as members of the ‘All-Russian People’ agreed with Russian leaders that Russians and Ukrainians are ‘one people’ (D’Anieri 2019, 162–163). Ukrainians in the Donbas who thought of themselves as ‘Russians’ were most likely the same as those who claimed to hold a Soviet identity. Russian and Soviet were de facto the same in the USSR.

The 2001 census recorded 17% of Ukraine’s population as Russians, but only 5% of these were exclusively Russian with the remainder exhibiting a mixed Ukrainian-Russian identity (The Views and Opinions of South-Eastern Regions Residents of Ukraine). During the 2014 crisis, sitting on the fence was no longer possible, and many Ukrainians who had held a mixed identity adopted a civic Ukrainian identity to show their patriotism. The proportion of the Ukrainian population declaring themselves to be ethnic Ukrainians increased to 92%. Currently, only 6% of Ukrainians declare themselves to be ethnically Russian, down from 22% in the 1989 Soviet census and 17% in the 2001 Ukrainian census (Osnovni Zasady ta Shlyakhy Formuvannya Spilnoyi Identychnosti Hromadyan Ukrayiny 2017, 5).

Between two opinion polls conducted in April and December 2014, mixed Russian-Ukrainian identities in southeastern Ukraine collapsed (O’Loughlin and Toal 2020, 318). Six years on, mixed identities have declined even further. In Dnipropetrovsk, those with mixed identities halved from 8.2 to 4.5%. In Zaporizhzhya and Odesa, mixed identities collapsed from 8.2 and 15.1% to 2 and 2.3%, respectively. Mixed identities were never strong in Kherson and Mykolayiv, where they collapsed to a statistically insignificant 0.6 and 1.6%, respectively. Kharkiv registered the lowest decline, from 12.4 to 7.7%. This is what Kharkiv scholar Zhurzhenko (2015) called the ‘end of ambiguity’ in eastern Ukraine. Ukraine no longer has a pro-Russian ‘east.’

Russian Intervention in the Decade Prior to the 2014 Crisis

Training and Support for Separatism in Ukraine

In November 2004, Russia supported a separatist congress in Severodonetsk in Luhansk oblast, organised by Yanukovych in protest to the Orange Revolution denying him his fraudulent election victory. In February 2014, a similar congress of the Ukrainian Front in Kharkiv was planned after Yanukovych fled from Kyiv, but failed to go ahead after regional leaders from southeastern Ukraine and the president failed to turn up.

Yanukovych’s plans in 2004 and 2014 drew on a long tradition of creating pro-Russian fronts. So-called ‘Internationalist Movements’ were established by the Soviet secret services in the late 1980s in Ukraine, Moldova, and the three Baltic States to oppose their independence. The Donetsk Republic Party, which is one of two parties ruling the DNR, is a successor to the Inter-Movement of the Donbas founded in 1989 by Andrei Purgin, Dmitri Kornilov, and Sergei Baryshnikov. Its allies were the Movement for the Rebirth of the Donbas and Civic Congress, which changed its name to the Party of Slavic Unity (Kuzio 2017c, 88–89).

The Donetsk Republic Party was launched in 2005, not coincidentally a year after the 2004 Orange Revolution with support from Russian intelligence (Na terrritorii Donetskoy oblasty deystvovaly voyennye lagerya DNR s polnym vooruzheniyem s 2009 goda 2014). The Donetsk Republic Party and similar extremist groups were provided with paramilitary training in summer camps organised by Dugin (see Shekhovtsov 2016, 2017, 2018, 253; Likhachev 2016). The Donetsk Republic Party was banned by the Ukrainian authorities in 2007, but continued to operate ‘underground’ with the connivance of the Party of Regions, which monopolised power in the Donbas.

Baryshnikov, Dean of Donetsk University in the DNR, and other leaders of the Donetsk Republic have always been extreme Russian chauvinists and Ukrainophobes. Baryshnikov believes that ‘Ukraine should not exist’ because it is an ‘artificial state.’ He admits, ‘I have always been against Ukraine, politically and ideologically,’ showing the long ideological continuity between the Soviet Inter-Movement and the Donetsk Republic Party (Na terrritorii Donetskoy oblasty deystvovaly voyennye lagerya DNR s polnym vooruzheniyem s 2009 goda 2014).

Baryshnikov unequivocally states that Ukrainians ‘are Russians who refuse to admit their Russia-ness;’ in other words, he supports the Tsarist Russian nationality policy of three branches of the ‘All-Russian People,’ which was rehabilitated by Putin. Baryshnikov supports the destruction of Ukrainian national identity ‘by war and repression,’ because it ‘can be compared to a difficult disease, like cancer’ (Judah 2015, XVI, 11, 150, 152–153).

In spring 2014, Russia’s information warfare and Russian neo-Nazis on the ground in Donetsk helped to swell the number of members of the hitherto marginal Donetsk Republic Party (Melnyk 2020). Toal (2017, 252) writes that many Donbas and Crimean Russian proxies were ‘genuine neo-Nazis.’ The Donetsk Republic Party (Na terrritorii Donetskoy oblasty deystvovaly voyennye lagerya DNR s polnym vooruzheniyem s 2009 goda 2014) is one of two ruling parties in the DNR after winning 68.3% of the vote in its fake 2014 ‘election.’

Russian Penetration of Ukraine’s Security Forces

Sakwa (2017a) and Matveeva (2018) seek to downplay Yanukovych as a friend of Russia and, in doing so, minimise Russia’s intervention in Ukrainian affairs prior to 2014. Sakwa (2017a, 159, 153) writes, ‘Yanukovych had never been a particular friend of Russia’ and ‘relations with Moscow during his presidency remained strained.’ This chapter provides evidence that this is not true. Russia penetrated Ukrainian security forces during Yanukovych’s presidency extensively (see Kuzio 2012).

Jonnson and Seely (2015) place Russia’s ‘full spectrum conflict’ in the long-term context of Russian subversion that, over a number of years, strove to weaken its opponents’ security forces and increase its ties with Russia, for example through pro-Russian political forces, Russian-language media, think tanks, and NGOs (Gonchar, Horbach, and Pinchuk 2020, 41–51). The work of Russian intelligence services and the strategic use of corruption are two of the most widely used Russian tools in its ‘full spectrum conflict.’ Russia’s biggest export has always been corruption – not energy.

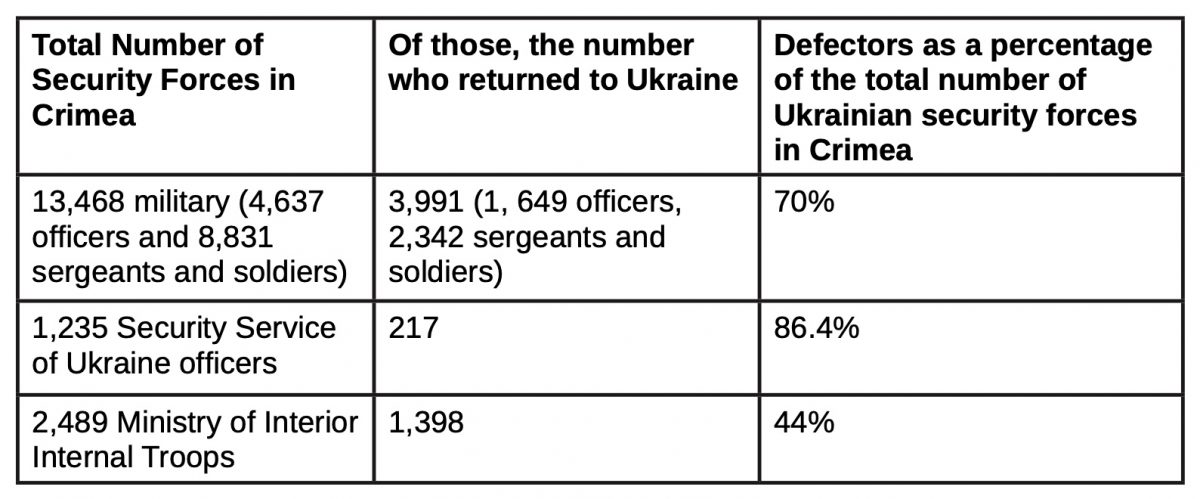

Security Service of Ukraine and military officers undertook espionage for Russia in the critical early stages of the conflict in 2014. The extent of Russia’s penetration is evident to the present day, with senior military and Security Service of Ukraine officers detained and charged with treason (Gonchar, Horbach and Pinchuk 2020, 3–22). When Poroshenko said in March 2015 that 80% of Security Service of Ukraine officers defected in spring 2014, his claim was met with disbelief in Crimea, but he was not exaggerating. The extent of Russia’s success in fomenting treason in Ukraine’s security forces in Crimea in spring 2014 can be seen in Table 5.1.

5.1. Table of Defections from Ukrainian Security Forces in Crimea, Spring 2014. Source: Gonchar, Horbach, and Pinchuk 2020, 13.

Violence and Nationalism during the Euromaidan

Claiming that a dominating influence of ‘Ukrainian nationalism’ in the Euromaidan is correlated with defining what is taking place in the Donbas as a ‘civil war,’ Keith Darden and Lucan Way (2014) exaggerate the influence of nationalism on the Euromaidan and portray ‘nationalists’ as ethnically based and originating from western Ukraine. Olga Onuch and Gwendolyn Sasse (2018, 28) provide a detailed counter-analysis, stressing the diversity of the protestors among whom they estimate nationalists accounted for only 5%, rising to 10–20% during the violence. The majority of protestors were ‘ordinary citizens’ with no previous history of political activity (Onuch 2014). Calling into ‘question the salience and stability of ethno-linguistic and regional identities,’ they argue that ‘a conceptualization of Ukrainian politics as being driven by ethno-linguistic or regional demands is too simplistic’ (Onuch and Sasse 2018, 30–31).

Exaggerating the influence of ‘Ukrainian nationalism’ is closely correlated with exaggerating regional divisions in Ukraine, repeating claims and stereotypes that are usually the exclusive prerogative of those who believe in an ‘artificial Ukraine’ and ‘two Ukraines’ (Sakwa 2015; Hahn 2018, Petro 2015). Kolstø (2016, 708) describes southeastern Ukraine as exhibiting ‘a more Russian character than the rest of Ukraine,’ which if true would have led to the success of Russia’s ‘New Russia’ project in 2014 (see Kuzio 2019a).

Ukrainian nationalists stereotypically painted as ‘western Ukrainian’ are often from eastern Ukraine. Nationalist Pravyy Sektor (Right Sector) Party leaders Dmytro Yarosh and Andriy Tarasenko are from Dnipropetrovsk, initial support for and leaders of the Azov battalion came from Kharkiv, Minister of Interior Arsen Avakov is a Russian-speaking Armenian from Kharkiv, and oligarch Kolomoyskyy is a Russian-speaking Jewish-Ukrainian from Dnipropetrovsk (as was his deputy Korban), while his other deputy (Filatov) was an ethnic Russian. The highest number of military veterans of the Donbas conflict are found in Dnipropetrovsk, Kharkiv, and Poltava (Kolumbet 2020), and the highest number of casualties of Ukrainian security forces are from Dnipropetrovsk (see 6.2 map).

President Yanukovych’s use of violence against protestors was lobbied for by Putin during his one-on-one meetings with the Ukrainian president and by Putin’s senior advisers Surkov and Glazyev. Violence during the Euromaidan ‘radicalised the protestors’ (Friesendorf 2019, 112). The Berkut forces that undertook human rights abuses and killed protestors were brought to Kyiv from Crimea, the Donbas, and elsewhere in eastern Ukraine in the belief that Kyiv-based Berkut would be unreliable. When these Berkut officers returned home, they were greeted as heroes and, in many cases, deserted to Russian forces in Crimea or joined Russian proxy forces in Donbas. The Berkut was disbanded by the Euromaidan revolutionaries after they took power (Crimea welcomes riot cops after murdering Euromaidan protestors 2014).

High levels of participation of eastern Ukrainians in volunteer battalions in 2014 (Aliyev 2019, 2020) grew out of the Euromaidan. In eastern Ukraine, football ‘ultras’ (members of fan clubs) and civil society activists created self-defence groups to protect local Maidans against Party of Regions and pro-Russian vigilantes. The most active of these self-defence groups were found in Kharkiv, Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhzhya, Odesa, and to a lesser extent Donetsk (Fisun 2014).

2012–2013: ‘Gathering Russian Lands’ versus Post-Modern EU

Some western scholars ignore Russia’s pressure on Yanukovych prior to the 2014 crisis and instead focus their entire criticism on the EU in 2014. The EU undertook a ‘reckless provocation’ in compelling Yanukovych ‘in a divided country to choose between Russia and the West’ (Cohen 2019, 17). Enlarging NATO to ‘Russia’s borders’ and the EU pushing its Association Agreement split Ukraine, because the east has a ‘shared civilization’ with Russia (Cohen 2019, 17). For a historian, it is surprising that Cohen (2019) believes that civilisations and identities are set in stone and never change. Western (or Russian) ‘political aggression’ allegedly undermined ‘centuries of intimate relations between large segments of Ukrainian society and Russia, including family ties’ (Cohen 2019, 83).

D’Anieri (2019) provides a more balanced critique of EU and Russian policies towards Ukraine in the run up to the 2014 crisis, pointing out that ‘Ukraine’s policy of picking which component of an agreement to adhere to would no longer be accepted’ (D’Anieri 2019, 192). D’Anieri (2019, 264) writes that Putin ‘put immense pressure’ on Yanukovych to not sign the Association Agreement (see also Sambanis, Skaperdas and Wohlforth 2017).

Impartial scholars would apportion blame on both the EU and Russia, both of which pressured Yanukovych to make a decision in their favour. The EU could not understand the depth of Russia’s hostility to Ukraine joining the Association Agreement because they did not believe it was aimed against Russia. The EU did not understand that Russia made no distinction between membership and Eastern Partnership offers of integration. ‘Putin saw the Association Agreement as threatening the permanent loss of Ukraine, which it had, since 1991, seen as artificial and temporary’ (D’Anieri 2019, 251).

The Ukraine crisis was ultimately a clash between a post-modern, twenty-first century EU and Russia, whose thinking had stagnated in the nineteenth century, or at the very least prior to World War II. This was evident in the rehabilitation of Tsarist Russian White émigré ideologies and thinking of Russia and its neighbours. Polish Foreign Minister Radek Sikorski rejected Russia’s ‘nineteenth-century mode of operating towards neighbours’ (D’Anieri 2019, 203). D’Anieri (2019, 276) believes that ‘Russia seeks an order based on the dominance of great powers that was widely accepted in the era prior to World War I.’

Medvedchuk has been Putin’s representative in Ukraine since at least 2004, the year Putin and Svetlana Medvedvev, wife of former Russian Prime Minister Medvedev, became godparents to his daughter Darina. Writing about Medvedchuk, Neil Buckley, and Roman Olearchyk (2017) say, ‘Many suspect him of being Mr Putin’s agent.’ Zygar (2016, 123) believes that Medvedchuk has long been the ‘main source of information about what was happening in Ukraine.’ Medvedchuk is the only person Putin has fully trusted in Ukraine, and he is ‘effectively Putin’s special representative in Ukraine’ (Zygar (2016, 167).

With accusations from his Soviet past of being a KGB informer, Medvedchuk ‘shared some of the “Ukrainophobia” of Moscow officialdom’ (Zygar 2016, 84). In the USSR, Medvedchuk had been a Soviet-appointed attorney for Ukrainian dissidents Yuriy Litvin and Vasyl Stus between 1979–1980. Although he was their ‘defence attorney’ he supported the court’s convictions, and Lytvyn and Stus died in the Siberian gulag in 1984 and 1985, respectively (Tytykalo 2020).

Medvedchuk and Glazyev implemented Putin’s goal of ‘gathering Russian lands’ by bringing Ukraine into the Russian World and CIS Customs Union (from 2015, the Eurasian Economic Union). In spring 2012, at the same time as Putin was re-elected, Medvedchuk launched the Ukrainian Choice political party, which resembled more a ‘front for the Kremlin than independent organization’ (Hosaka 2018, 341). Russia and its representatives in Ukraine promoted Eurasian integration for its alleged benefits of Ukrainian access to markets and cheaper gas deals (Molchanov 2016). According to them, Ukraine could only maintain its identity at the centre of Eurasia rather than on the edge of Europe; Ukraine’s growing trade with the EU since 2014 shows this to be untrue.

Russia’s active measures against Ukraine were launched in early 2013, which targeted ideological, political, economic, and information factors (Hosaka 2018). In summer 2013, Medvedchuk and Glazyev devised a strategy that included a trade war and a range of other policies to pressure President Yanukovych to turn away from the EU Association Agreement and join the CIS Customs Union (O komplekse mer po vovlecheniyu Ukrainy v evraziiskii integratsionyi protsess 2013). This strategy may have been what Belarusian President Lukashenka was referring to when he said that he had seen Russian plans to invade Crimea and ‘New Russia’ in May 2013 (Leshchenko 2014, 215).

Putin did not fully trust Yanukovych and threatened to back Medvedchuk in the 2015 elections if he did not withdraw from the EU Association Agreement (Hosaka 2018; Melnyk 2020, 18). Putin and Medvedchuk’s allies worked with the Russian nationalist wing of the Party of Regions led by Igor Markov, Oleg Tsarev, and Vadym Kolesnichenko. All three supported Russia’s interventions and military invasion in 2014. Kolesnichenko was a co-author of the divisive 2012 language law and was one of the organisers of the failed Ukrainian Front in Kharkiv (Kulick 2019, 359).

The Medvedchuk-Glazyev strategy was fully implemented. One part of the strategy was ‘Operation Armageddon,’ launched on 26 June 2013, just three weeks after Prime Minister Nikolai Azarov agreed to bring Ukraine into the CIS Customs Union as an ‘observer.’ One of ‘Operation Armageddon’s’ most important periods of activity was from 1 December 2013, when the Euromaidan took off, to 28 February 2014, a day after Russia launched its invasion of Crimea. ‘Operation Armageddon’ was complimented by ‘Operation Infektion,’ launched in February 2014 and continued to the present day (Nimmo, Francois, Eib, Ronzaud, Ferreira, Hernon, and Kostelancik 2020). ‘Operation Armageddon’ was a ‘Russian state-sponsored cyber espionage campaign’ designed to give Russia military advantage in any future conflict with Ukraine and, to this end, it targeted Ukrainian government, military, and law enforcement to obtain an insight into Ukrainian intentions and plans (Operation Armageddon 2015).

In summer 2013, Ukraine was subjected to a trade boycott and demands for payment of its debts to Gazprom, actions that were combined with a ‘massive diplomatic offensive against Ukraine’ (Svoboda 2019, 1694). Putin and Yanukovych held numerous one-on-one meetings prior to and during the Euromaidan, which ‘underlined the importance of the issue for Russia and the seriousness of the situation’ (Svoboda 2019, 1695). In the year before the outbreak of military conflict, Russia ‘combined diplomacy, propaganda, economic pressure, and even the threat of military action’ (Svoboda 2019, 1700; see also Haukkala 2015).

Included in the Medvedchuk-Glazyev strategy was an invitation to Putin and Kirill to speak at the July 2013 Kyiv conference to promote ‘Orthodox-Slavic values’ and Ukraine’s civilisation choice in favour of the Russian World (D’Anieri 2019, 193; Kishkovsky 2013; Zygar 2016, 258). As Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church, Kirill had strongly identified with the Russian World since becoming Patriarch in 2009 and supported the rehabilitation of the Tsarist Russian nationality policy of three eastern Slavic branches of the ‘All-Russian People.’ Kirill agreed with Putin that Russians and Ukrainians were ‘one people’ (Plokhy 2017, 331). As ‘Holy Rus,’ the three eastern Slavs were the core of the Russian Orthodox Church with the Russian World a contemporary reincarnation of ‘Kievan Russia’ (Kyiv Rus).

Putin and Kirill used the celebrations of the anniversary of the 1,025th anniversary of the Christianisation of Kyiv Rus to rebuild a contemporary eastern Slavic Union in the Russian World. Eastern Slavic and Russian World values were claimed to be superior to European liberal values, a message that Russia has increasingly promoted as it has reached out to and supported populist nationalist and neo-fascist groups in Europe hostile to the EU (see Shekhovtsov 2018).

Putin told Medvedchuk’s conference: ‘The baptism of Rus was a great event that defined Russia’s and Ukraine’s spiritual and cultural development for the centuries to come. We must remember this brotherhood and preserve our ancestor’s land’ (D’Anieri 2019, 193–194). In a clear reference to himself as the ‘gatherer of Russian lands,’ Putin described ‘Russians’ as the most divided people in the world (Laruelle 2015; Teper 2016).

‘Full Spectrum Conflict’ and the 2014 Crisis

Downplaying Russia’s Military Invasion

Scholars who use the term ‘civil war’ ignore 10 important factors that took place in the decade prior to and during spring 2014:

- Russian interference in the 2004 presidential elections;

- Russian support for and training of separatists and extremist Russian nationalists;

- Russian backing for an alliance between the Party of Regions and Crimean Russian nationalists-separatists;

- Evolution of Russian views away from the Soviet concept of close but different Russians and Ukrainians towards Tsarist Russian and White émigré denial of Ukraine and Ukrainians;

- President Medvedev’s (2009) open letter laying out demands which President Yanukovych fulfilled;

- Russian infiltration and control over Ukrainian security forces during Yanukovych’s presidency and how this led to defections, treason and leakage of intelligence in the 2014 crisis;

- Implementation of Putin’s ‘gathering of Russian lands’ after his re-election in 2012–2013, including pressure on Yanukovych to drop Ukraine’s integration into the EU;

- Russia offering exile to Yanukovych and other Party of Regions leaders who had stolen upwards of $100 billion from Ukraine and committed treason (Roth 2019);

- How Russia’s annexation of Crimea, ‘Russian spring’ and ‘New Russia’ project impacted upon Ukrainian policy decisions to combat Russian proxies in the Donbas; and

- Focusing on only Russian military boots on the ground while ignoring the many components of Russian ‘full spectrum conflict’ (Jonsson and Seely 2015) which are chronicled in Table 5.2.

Denial, obfuscation, minimising, or ignoring evidence of Russia’s ‘full spectrum conflict’ is used to give credence to the claim that a ‘civil war’ is taking place in Ukraine. Matveeva (2018, 112) writes that Putin ‘was elusive, zigzagging, and non-committal.’ In support of her claim that separatists were not Russian proxies, Matveeva (2018, 217) writes that ‘military supplies switched on and off,’ ignoring many other aspects of Russian involvement and Russia’s intervention prior to the Euromaidan and immediately after Yanukovych fled from Kyiv.

It cannot be true, as Sakwa (2017a) writes, that Russia sought to extricate itself from the Donbas at the same time as it built up a huge army and military arsenal controlled by GRU (Russian military intelligence) officers and 5,000 Russian occupation troops based in the DNR and LNR. Cohen’s (2019) denial of Russia’s military invasion in Ukraine is in keeping with his denial of Russian hacking of the 2016 US elections, chemical weapons attack against Russian defector Sergei Skripal in Britain, and every other nefarious action of which Russia is accused of undertaking. Just some of the Russians who have been poisoned include Navalnyi, Anna Politkovskaya, Vladimir Kara Murza (twice), Yuri Schchekochikin, Emilian Gebrev in Bulgaria, Alexander Litvinenko, Alexander Perepilichny, and Skripal in the UK.

Hahn (2018, 268) downplays Russian forces in spring 2014 as ‘negligible’ and ‘non-existent,’ and minimises Russia military intervention. In writing that ‘it is fundamentally a civil war,’ Hahn (2018, 270) views the conflict taking place between ‘western Ukrainian nationalists’ and ‘good,’ pro-Russian eastern Ukrainian Russian speakers. Western Ukrainian ‘fascists’ came to power in a coup d’état during the Euromaidan and made Russian speakers a ‘stigmatised minority’ (Hahn, 2018, 45), closed Russian language media, and demonised President Putin. Putin’s policies are described as ‘reactive and defensive’ and as a ‘countermove to mitigate the loss incurred in and potential threat from Kiev’ (Hahn 2018, 21). This is a novel way to describe the annexation of a neighbour’s territory. Putin had ‘solid arguments’ for ‘Russian intervention in the crisis and especially in Crimea’ (Hahn 2018, 237).

Serhiy Kudelia (2017, 226) applies ‘civil war’ to the entire period until summer 2014, when Russia invaded Ukraine. Kudelia (2017, 228) blames only Ukraine for launching ‘the military stage,’ a view he shares with Sakwa (2015), Matveeva (2016, 2018), and Cohen (2019). Similarly, Matveeva (2018, 272) writes, ‘Before the crisis, Moscow’s role in Ukraine was not particularly active,’ and ‘Moscow did not support any independent activism of a pro-Russian nature in Ukraine.’ Hiroaki Kuromiya (2019, 252, 257), the leading historian of the Donbas, believes that ‘violence was encouraged and supported by Moscow’ because, on their own, ‘the local separatists were simply not determined enough to engage in war.’

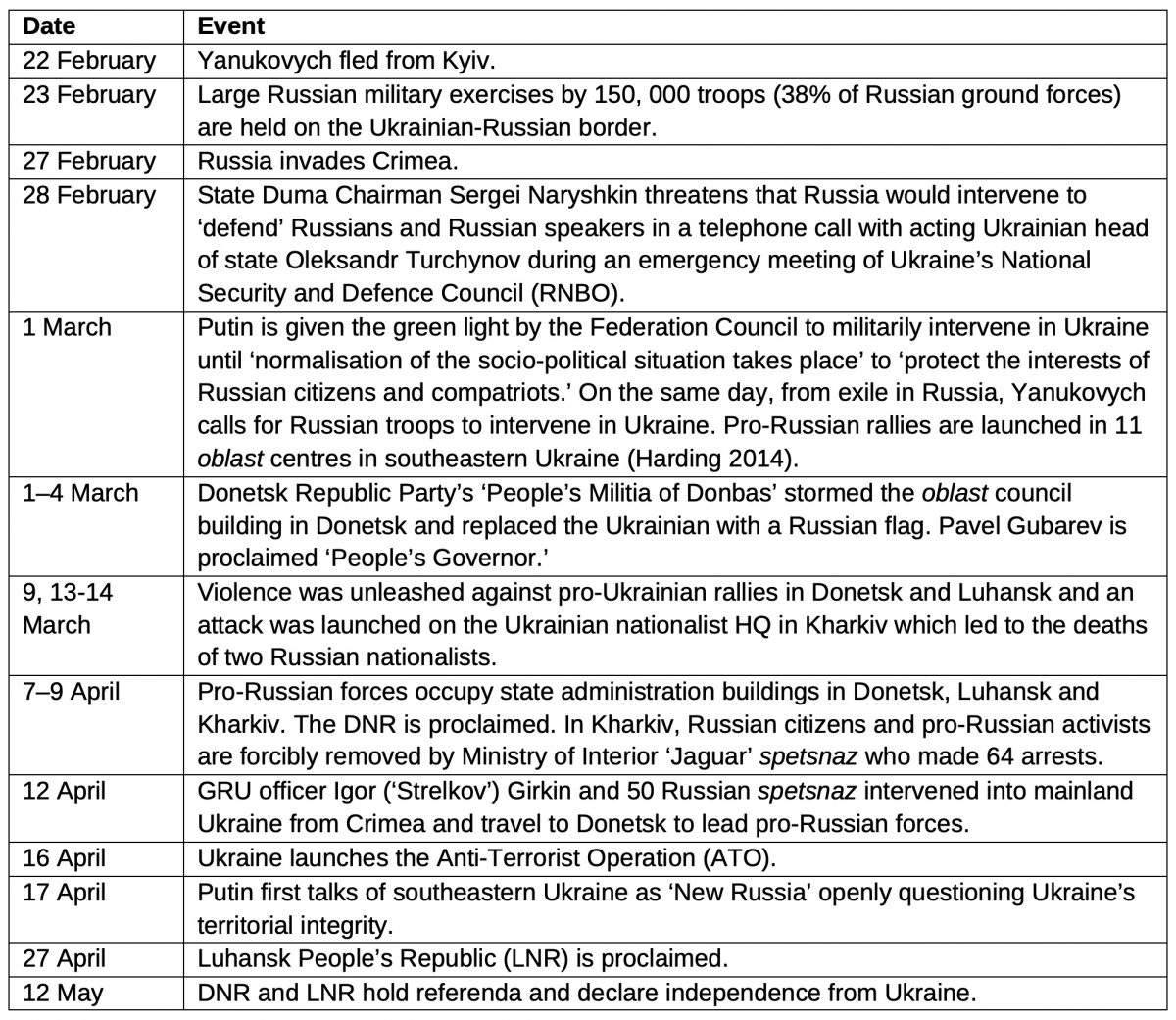

5.2. Russian ‘Full Spectrum Conflict,’ February–April 2014. Source: Compiled by author

Russian Intelligence

Russian intelligence actively financed, trained, and cooperated with anti-Maidan activists in the decade before and during the Euromaidan (see The Battle for Ukraine 2014). In 2009, Russian diplomats in Odesa and Crimea were expelled for supporting separatists. Russian volunteers who were trained in Russian camps joined the conflict. There is a mass of evidence, collected by the Security Service of Ukraine, that Russian intelligence officers undertook training and coordination with, and providing leadership to separatist forces throughout 2014. Intercepted telephone conversations of FSB intelligence officer Colonel Igor Egorov (‘Elbrus’) (2020), who was first deputy commander of the ‘New Russia’ army, provide evidence that he coordinated the so-called DNR Ministry of Defence (Bellingcat 2020a). Egorov (2020) is a senior officer from the FSB elite spetsnaz unit, which is a successor to the KGB’s V Department’s elite Vympel spetsnaz unit. Bellingcat’s (2020b, 2000c) research and captured documents released by the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) show the close ties between Surkov, Yevgeny Prigozhin, Wagner Group mercenaries, the Moscow headquarters of GRU, and FSB and Russian intelligence on the ground in Ukraine, who coordinated and supplied military equipment to Russian proxies in the Donbas in 2014.

The 12 April 2014 invasion of mainland Ukraine by GRU officer Girkin and 50 Russian spetsnaz soldiers is evidence of Russian military boots on the ground at the beginning of the conflict. A day after his intervention in mainland Ukraine, the Security Service of Ukraine published intercepted telephone calls between Girkin (2014) and his handlers in Moscow, including to and from his Russian telephone number. His invasion was a ‘key escalatory move’ (Sambanis, Skaperdas and Wohlforth 2017, 32). As Girkin had participated in Russia’s annexation of Crimea and intervened in mainland Ukraine from Russian-occupied Crimea, he undoubtedly ‘coordinated his actions with Moscow, above all with Glazyev’ (Zygar 2016, 285). Girkin ‘acted in accordance with a directive from Moscow’ (Kuromiya 2019, 257; Sokolov, 2019). Girkin admitted that he had coordinated his action with Crimean Prime Minister Aksyonov. Girkin’s spetsnaz soldiers were augmented the following month by Chechen mercenaries loyal to President Ramzan Kadyrov, who fought in the Donbas between May–July 2014 (Vatchagaev 2015).

Mercenaries in the Service of Russian Nationalism (Imperialism)

‘Political tourists’ were bussed into Kharkiv and other Ukrainian cities from Russia or into Odesa from the Russian-occupied Trans-Dniestr region of Moldova to act as fake Ukrainian protestors (Shandra and Seely 2019). It is not coincidental that rallies simultaneously began on 1 March 2014 in 11 southeastern Ukrainian cities on the same day that Putin received authorisation from the Federation Council to intervene militarily in Ukraine. Kudelia’s (2014) argument that the violent seizure of official buildings ‘happened sporadically and in a decentralized manner’ is simply naïve and unbelievable. It is improbable that rallies would have broken out coincidentally on the same day in 11 locations when only 11.7% of the population in southeastern Ukraine supported the seizure of buildings and a very high 76.8% opposed this action. In Donetsk and Luhansk, where there was the highest support in the eight oblasts of southeastern Ukraine, only 18.1 and 24.4% of people, respectively, supported the seizure of buildings, while a much higher 53.2 and 58.3% opposed such action (The Views and Opinions of South-Eastern Regions Residents of Ukraine).

Yevhen Zakharov, head of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, believes that ‘these pan-Ukrainian rallies were carefully co-ordinated’ (Harding 2014). Pro-Russian activists admitted that, before they stormed the State Administration in Kharkiv, they ‘met with Russian intelligence agents who were working in the east’ and who were from ‘the Russian military and intelligence agencies’ (Jones 2014). In Kharkiv, ‘20 to 40 buses’ from the nearby Russian city of Belgorod arrived in the centre’ (Harding 2014). Kharkiv journalist Andriy Borodavka estimated that ‘around 200’ Russian citizens had been bused from Russia to Kharkiv. ‘They delivered hardcore Kremlin activists, he said, some dressed in military-style fatigues. They waved Russian flags and cried: ‘Russia, Russia’ (Harding 2014). ‘Together with local thugs, the “tourists” stormed the main administrative building, at the opposite end of the square, and evicted the Ukrainian nationalists who had been occupying it, brutally beating several of them,’ Luke Harding (2014) reported from Kharkiv. A clash outside the Kharkiv headquarters of the Ukrainian nationalist organisation Patriots of Ukraine led to two attackers from the pro-Russian Oplot (Bulwark)[1] being shot and killed (Harding 2014).

Oplot grouped together athletic members of a Kharkiv sports club who had acted as Ministry of Interior vigilantes during the Euromaidan and were most likely involved in some of the killings of protestors. The Oplot members interviewed by the PBS (Public Broadcasting Service) for its documentary on Kharkiv had admitted to being financed and trained by Russian intelligence to attack Euromaidan supporters (Jones 2014). After the failure of the Kharkiv People Republic, Oplot members fled to the DNR and joined Russian proxy forces. At the same time, as part of a Russian-sponsored terrorist campaign throughout Ukraine, Oplot were behind terrorist attacks in Kharkiv; one such attack in February 2015 killed four people (see Kuzio 2015b, 2015c).

Moscow student blogger Arkady Khudyakov replaced the Ukrainian flag on the roof of the Kharkiv State Administration building with a Russian flag. He posted video and photos of his exploits on the social network site LiveJournal’ (Harding 2014). It cannot be a coincidence that a Russian flag was also raised by Russian citizen Mikhail Chuprikov on Donetsk city hall on the same day as in Kharkiv (Roth 2014). Rallies, beatings, and seizures of state buildings were ‘secretly organized, financially backed, and ideologically underpinned by the Russian leadership’ (Gomza and Zajaczkowski 2019).

The Glazyev tapes ‘vividly illustrate Moscow’s covert support for the still unarmed anti-government protests in Ukraine several weeks before the actual war started’ (Umland 2016). Russia intervened to organise, support, and enlarge pro-Russian rallies ‘immediately after the victory of the Maidan revolution in early 2014’ (Umland 2016). Russia ‘actively fanned the flames of pre-existing ethnic, cultural and political tensions in the region’ (Umland 2016).

Russian ‘political tourists’ and neo-Nazis, with the assistance of Russian intelligence, tipped peaceful anti-Kyiv protests into violence and then armed insurgencies. Russia’s ‘full spectrum conflict’ (Jonsson and Seely 2015) had the effect of ‘emboldening insurgents in eastern Ukraine to ramp up demands and take armed actions’ (Sambanis, Skaperdas and Wohlforth 2017, 30). The escalation of protests into a full-blown war would have been unlikely without ‘increased expectations of intervention’ (Sambanis, Skaperdas and Wohlforth 2017, 30). Expectations of Russian military invasion in ‘New Russia’ following that in Crimea influenced both sides to persevere throughout 2014 (Sambanis, Skaperdas and Wohlforth 2017, 31). The arrival of Russian neo-Nazis in the Donbas led to violent attacks against pro-Ukrainian protestors, confirming that external intervention was a central factor in the transition from peaceful protests to violent conflict. On 5 March 2014, Russian neo-Nazi extremists violently attacked pro-Ukrainian protestors in Donetsk on the same day that Rossija-1 TV channel aired inflammatory reports of US mercenaries arriving in the Donbas with Pravyy Sektor Ukrainian nationalists to ethnically cleanse Russians and Russian speakers (Hajduk and Stepniewski 2016, 45).

It would be truly incredulous to believe that Russian intelligence was not involved in coordinating pro-Russian ‘uprisings’ in southeastern Ukraine, or that they were not behind Chuprikov in Donetsk and Khudyakov in Kharkiv. ‘I don’t believe that in one day across the entire east and south of Ukraine, the same protest breaks out,’ former head of the politics division in Donetsk city council Viktor Nikolaenko said (Ioffee 2014). ‘Then all of a sudden, an armed resistance rises. I’ve been in politics too long to believe in such a coincidence. The synchronization is obvious,’ Nikolaenko added (Ioffe 2014). That most of the violent protestors were actually Russian ‘tourists’ proved to be comical in Kharkiv, where they took control of the Opera House mistakenly believing the building to be the city hall.

Putin, Suslov, Medvedchuk, and Glazyev aimed to transform these protests into pro-Russian uprisings, which would take control of oblast and city councils and state administrations. These councils would vote to refuse to recognise the Euromaidan revolutionary government in Kyiv as Ukraine’s legitimate authorities (on Kharkiv see Harding 2014), which would be followed by the establishment of ‘people’s republics.’ These so-called ‘people’s republics’ would invite Russian forces to intervene to ‘protect’ ethnic Russians and Russian speakers from ‘Ukrainian nationalists.’

Russia’s strategy was to have the fig leaf of ‘Ukrainians’ supporting these goals, and then ‘Moscow would support them’ (Zygar 2016, 284) in ‘a convincing picture of genuine local and even internal support for Russian ideas in Ukraine’ (Shandra and Seely 2019, 22). In reality, these actions were ‘micromanaged by Kremlin officials’ (Shandra and Seely 2019, 38). The low number of participants in pro-Russian rallies in ‘New Russia’ and weak support for pro-Russian goals found in opinion polls point to the artificiality of these pro-Russian ‘uprisings’ and why they failed (Kuzio 2019a).

These different aspects of Russia’s ‘full spectrum conflict’ (Jonsson and Seely 2015) are ignored by many scholars writing about 2014 in Ukraine (Cohen 2019). Kudelia (2017, 214) incredulously writes, ‘Without question Russia exploited these events, but it did not define them.’ This is not true; different aspects of Russian ‘full spectrum conflict’ (Jonsson and Seely 2015) had the goal of ‘converting a marginal movement into a mass phenomenon’ (Wilson 2015, 645). Leaks of Surkov’s emails (Shandra and Seely 2019), Glazyev’s telephone conversations (Umland 2016), and a February 2014 Russian strategy document (Russian ‘road map’ for annexing eastern Ukraine) provide abundant evidence of Russian intervention during the Euromaidan and in spring 2014.

Putin’s Signalling and Nationalist (Imperialist) Coalitions

Erin K. Jenne (2007) believes that external lobbying and external patrons are key factors in determining the mobilisation of minorities because they signal an intention to intervene, which radicalises demands towards the central government. Actual or expected intervention shapes bargaining calculations (Sambanis, Skaperdas and Wohlforth 2017, 27). Pro-Russian forces and Russian nationalists understood Putin’s signalling as Russia’s intention to either annex ‘New Russia’ in the same way as it had Crimea or to detach the region and create a semi-independent state aligned with Russia in the Eurasian Economic Union.

In February–April 2014, the presence of Russian nationalists (imperialists), activities of Russian intelligence operatives, and invasion into mainland Ukraine by Girkin’s Russian spetsnaz (chronicled in Table 5.2) at the same time as Russia annexed Crimea heightened fears among Ukrainian policymakers that Russia was seeking to dismember Ukraine. This is clearly evident in the minutes of the emergency meeting of Ukraine’s National Security and Defence Council (RNBO) held on 28 February 2014 (National Security and Defence Council 2016). Melnyk (2020, 18) believes that the annexation of Crimea and destabilisation of southeastern Ukraine should be treated together.

Foreign powers have intervened in the majority of civil wars and, the longer the civil war continues, the more likely it is that there will be outside intervention. Sambanis (2002, 235) writes that ‘expected intervention has a robustly positive and highly significant association with civil war.’ Foreign powers should be reasonably confident of success; the projected time horizon of the intervention is short and domestic opposition is minimal. These three factors were only partly present in Ukraine in 2014 (Sambinis 2002).

In February 2014, Putin took a gamble when Russian forces invaded Crimea, but they met no resistance; large-scale infiltration of Ukrainian security forces by Russian intelligence led them to calculate that Ukrainian resistance would be minimal. Russia’s invasion of Crimea ‘radically transformed expectations of intervention in other Ukrainian regions, notably Donbas’ (Sambanis, Skaperdas and Wohlforth 2017, 27). In Kyiv and the Donbas, Russia’s occupation of Crimea was viewed as a blueprint by pro-Russian groups, which would be followed by Russia further detaching territories from southeastern Ukraine (Osipan 2015, 138).

It is highly improbable that Russia spontaneously launched a military operation on 27 February 2014, only five days after Yanukovych fled from Kyiv. D’Anieri (2019, 230) writes, ‘At a minimum, Russia had made plans for the military seizure of Crimea well in advance.’ Plans for Crimea were prepared as a contingency during earlier crises in Russian-Ukrainian relations in 2004, between 2008–2009, and after Putin’s 2012 re-election. Sanshiro Hosaka (2018, 363) rules out a last-minute improvisation and views Russia’s invasion of Crimea as a ‘well-considered and proactive move’ to maintain Ukraine within Russia’s orbit.

Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea strongly influenced perceptions of Russian policies towards mainland Ukraine among Ukrainian policymakers. The lack of Ukrainian resistance in Crimea ‘incentivized the Kremlin to press for continuing gains’ (Bowen 2019, 334). Russia’s annexation of Crimea led to a belief that ‘the Kremlin would unleash in the Donbas a similar operation to that in Crimea’ which, in turn, influenced the decisions and expectations of Kyiv and pro-Russian forces (Gilley 2019, 323).[2] Hosaka (2018, 324–325) believes that Crimea’s annexation was part of Russia’s ‘strategic goal’ of ‘keeping Ukraine in Russia’s orbit.’

Soviet and Russian nationalist (imperialist) nostalgia ‘was already present in the ‘red brown’ (communist-fascist) coalition of 1993’ (D’Anieri 2019, 256), which came to the fore in the ‘Russian spring’ (see Melnyk 2020, 22). In spring 2014, Putin’s rhetoric signalled support for the goals of the ‘brown’ (fascist), ‘white’ (monarchist and Orthodox fundamentalist), and ‘red’ (Communist) Russian nationalist (imperialist) coalition (Laruelle 2016a). The ranks of Putin’s senior advisers on Ukraine (Surkov 2019, Glazyev 2020) and influential Russians (Dugin 2014) are dominated by Russian nationalists (imperialists) and anti-Semites (see Likhachev 2016; Laruelle 2016a; Shekhovtsov 2017). Putin’s rhetoric emboldened Russian nationalists (imperialists) to believe that Russian authorities were no longer abiding by treaties they had signed with Ukraine, and they therefore viewed Ukraine as a target for dismemberment or re-configuration into a loose confederation aligned with Russia in the Eurasian Economic Union (Melnyk 2020, 28–29).

Russian Information Warfare

Most western scholars ignore Putin’s obsession with Ukraine and Ukrainophobia, which permeates Russia’s information warfare and was analysed in chapter 4. Matveeva (2018) devotes little space to Russia’s massive information war against Ukraine, which played a central role in the 2014 crisis; while not denying the power of the Russian media at the same time Matveeva (2018) barely mentions it. It is untrue that Russia had ‘few soft power instruments at its disposal’ prior to and in 2014 (Matveeva 2018, 273).

Russian information warfare and disinformation were central components of its ‘full spectrum conflict’ towards Ukraine. Talking of Kharkiv, Borodavka admitted, ‘Yes, the FSB plays a role in supporting pro-Russian groups. But the most important vector is the Russian media’ (Harding 2014) in mobilising violent conflict and political instability. The Russian media ‘have effectively been on a war footing since the spring of 2014’ (Fedor 2015, 1). Hysteria, hatred, aggression, and xenophobia have ‘reached alarmingly high levels,’ and political murders and violence have ‘become unremarkable’ (Fedor 2015, 1, 5). Russia’s information warfare was that of the ‘language of hate’ from its inception (Bonch-Osmolovskaya 2015, 182), creating a climate favourable to local support for military and political operations in Crimea and Donbas (Hajduk and Stepniewski 2016, 46–47). Protestors were radicalised by Russian propaganda and information warfare and Russian hybrid warfare transformed protestors into an armed insurgency (Wilson 2015).

An information campaign of this nature and intensity would be viewed by every country it would be directed against as an act of aggression by a foreign power. NATO’s understanding of the growing importance of Russian cyber warfare, information warfare, and disinformation led to the opening of a NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence in Riga, a Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence in Tallinn, and a Communications and Information Agency in The Hague. To counter Russian disinformation, the EU created the East StratCom Task Force (which publishes the excellent weekly Disinformation Review), and the US government established a Global Engagement Centre.

Russia as a Great Power and Ukraine’s ‘Limited Sovereignty’

Sakwa (2017a, 106, 131) claims that Russia is not a ‘genuine revisionist power’ because it aims to ‘ensure the universal and consistent application of existing norms.’ Russia has pushed back since February 2007, when Putin gave a speech to the Munich Security Conference, after which ‘the stage was set for confrontation’ and Russia was not ‘seeking to destroy the sovereignty of its neighbors’ (Sakwa 2017, 27, 35). One can only read this with incredulity following Russia’s 2008 recognition of the independence of the Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia and annexation of Crimea. Ukrainian opinion polls show that nearly three-quarters (71%) of Ukrainians believe that Russia is seeking to destroy Ukrainian sovereignty (Perspektyvy Ukrayinsko-Rosiyskykh Vidnosyn 2015, 61).

Sakwa (2017a, 263) denies that Russia never sought ‘a return to spheres of influence,’ which is untrue because Russia believes it can be a great power only by controlling and the West recognising its exclusive sphere of influence in Eurasia. Russia has always sought US and international recognition of Eurasia as its exclusive sphere of influence. Mikhail Suslov (2018, 4) writes that ‘the idea of a sphere of influence’ is hardwired into the ‘Russian World’ imagery. The Russian World demands an exclusive Russian sphere of influence over the three eastern Slavs based on ‘common’ culture, values, language, and religion. The ‘Russian’ presence abroad is where Russia’s sphere of influence extends, especially in Ukraine and Belarus, which are viewed as branches of the ‘Russian nation.’ ‘The Russian World is where Russians are’ (Suslov 2018) and, if Ukrainians and Russians are ‘one people,’ then Ukraine is an inalienable part of the Russian World.

Similarly, Laruelle (2015, 96) believes that there is no nationalism in Russian foreign policy and that Putin ‘does not advance a nationalist agenda.’ At the same time, Laruelle (2015) confusingly writes that nationalism (in this book, it is defined as imperialism) does shape Russian foreign policy on identity questions, such as ‘Russians’ as a divided nation, and in other areas. A rehabilitation of Tsarist Russian and White émigré views of Ukraine and Ukrainians is evidence of a nationalistic (imperialistic) Russian foreign policy. Beyond western political scientists working on Russia, there are few government policymakers, think tank experts, or journalists who would believe that Russian foreign policy is not nationalist.

W. Wayne Merry (2016) views Putin’s war against Ukraine as a clash of sovereignties because Russia is at odds with the UN and international law in not viewing Ukraine and most former Soviet states as ‘sovereign’ entities. Claiming the status of first among equals for itself and seeking a nationalist (imperialist) primacy of its own interests, Russia is in ‘pursuit of suzerainty,’ whereby a great power exercises control over its neighbours’ external relations while giving internal autonomy to a satrap, such as Lukashenka. The Lukyanov Doctrine, now confined to the territory of the former USSR, is a ‘conceptual successor’ to the Brezhnev Doctrine, which the USSR used to justify invasions of eastern European communist states (Gretskiy 2020, 21). Since 1991, Russia has pursued a Lukyanov Doctrine by undermining the territorial integrity of former Soviet republics, aggravating their security threats, promoting separatism, using economic blackmail, and training and equipping non-state actors (such as the Donetsk Republic Party) for military purposes (Gretskiy 2020, 7).

The Lukyanov Doctrine provided the ideological underpinnings for Russia’s belief in spring 2014 that it had a right to intervene in what it viewed as a disintegrating and chaotic Ukrainian state, which it had always believed was ‘failed,’ ‘artificial,’ and ‘Russian.’ After Yanukovych fled from Kyiv, ‘The general feeling (in Moscow) was that Ukraine had ceased to exist as a state’ (Zygar 2016, 283). This factor should be understood within the broader context of Russia viewing Ukraine as an artificial state together with Russia’s view of its Eurasian neighbours possessing limited sovereignty.

Editor of Russia in Global Affairs, Fyodr Lukyanov, does not deny that Russia intervened in spring 2014, saying, ‘It would be strange if it weren’t there’ (Ioffe 2014). Russian had two goals. The first goal was to show to the international community that Ukraine could not control all of its territory, and the second goal was to prevent the emergence of an ‘anti-Russian’ Ukraine (Ioffe 2014).

Military Invasion

Jonsson and Seely (2015) define ‘full spectrum conflict’ as combining military, informational, economic, energy, and political components. Russian aggression towards Ukraine included ‘a mixture of strategic 21st century tactics, maskirovka [Russian military deception], and hybrid warfare’ (Bodie 2017, 306). Military (kinetic violence) and non-military components came under one command. Aiming to avoid a large-scale war, ‘full spectrum conflict’ fell back on the use of the Russian military if its proxy forces were on the verge of defeat, as in August 2014 when Russia invaded Ukraine.

Military forms of hybrid warfare only work when there is popular support among the local population, which clearly did not exist in six of the eight oblasts of southeastern Ukraine; even in the Donbas, the population was divided. A full-scale Russian invasion would have ‘destroyed the fiction that Russia was not involved’ (D’Anieri 2019, 245) and would have had two strategic consequences. The first consequence would have been that the Russian public would have found out they are at war with Ukraine. Until now, Russians, with limited access to independent sources of information, have believed the myth of Russia’s non-involvement in the ‘civil war’ in Ukraine. It is highly improbable that Russian information warfare could spin Russian forces as openly fighting a war against Ukrainians. The second consequence is that a Russian invasion would have led to a full-blown crisis with the West, NATO placed on high alert, and the introduction of a far more severe sanctions regime, similar to that pursued against Iran.

In a detailed study of Russian control over the parts of Donbas it has occupied, Donald N. Jensen (2017) brushes this aside as an outcome resulting from ‘civil war’ or ‘popular uprising,’ and believes that the conflict was manufactured by Russia to prevent Ukraine’s integration into the West. Jensen (2017) documents how Donbas proxies were controlled by Russia from its inception with all major military decisions made in Moscow. Evidence of Russia’s invasion is available from an array of official sources, think tanks, and academic studies, including within Ukraine. Ukrainian views of a Russian-Ukrainian War, as opposed to a ‘civil war,’ are echoed by international organisations, European and North American journalists, and governments (Harding 2016, 304–305). On a weekly basis, the US Mission to the OSCE refutes Russia’s claims of a ‘civil war’ taking place in Ukraine: ‘We all know the truth – the brutal war in Donbas is fomented and perpetuated by Russia’ (Ongoing Violations of International Law and Defiance of OSCE Principles and Commitments by the Russian Federation in Ukraine 2018). US Ambassador Kurt Volker, former Special Representative for Ukraine Negotiations, has said, ‘Russia consistently blocks expansion of OSCE border mission and its forces prevent SMM from reliably monitoring the border as it sends troops, arms, and supplies into Ukraine; all while claiming it’s an “internal” conflict and spouting disingenuous arguments about Minsk agreements.’

Russia supplies training, leadership, fuel, ammunition, military technology, and intelligence, and there is a presence of Russian military, intelligence, mercenaries who fought in frozen conflicts in Eurasia, members of organised crime, and nationalist extremists. Control is exercised through Kremlin ‘curators,’ such as Suslov in 2014–2020. Military ‘advisers’ and Russian intelligence coordinate their policies through the Centre for the Management of Reconstruction. The Inter-Ministerial Commission for the Provision of Humanitarian Aid for the Affected Areas in the Southeast of the Regions of Donetsk and Luhansk acts as Russia’s shadow government.

Andrew S. Bowen (2019, 325) believes that a Russian strategy only became clear in late 2014. Nevertheless, large military exercises on the border, and training and coordination of non-state actors were used by Russia from the inception of the crisis, and ‘Russia’s supporting hand was evident from the beginning’ (Bowen 2019, 325). From the beginning of the crisis, ‘Russian troops, intelligence officers, and political advisers were alleged to be either supporting or directly controlling the separatists’ (Bowen 2019, 331). From May 2014, there is little doubt, as noted by the UNHCHR during the period between 2 April-6 May 2014, that ‘[t]hose found to be arming and inciting armed groups and transforming them into paramilitary forces must be held accountable under national and international law’ (Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine 2014).

From May 2014, Russia has provided surface-to-air missiles, which were used to shoot down five Ukrainian helicopters, 2 fighter jets, an AN-30 surveillance plane, and Ilyushin IL-76 over the course of two months. Russian artillery fired a huge number of shells into Ukraine over July and August 2014. Because of a high number of casualties among Russian proxies and Russian forces from Ukrainian air power, Russia sought to change the military balance on the battlefield by suppling the sophisticated surface-to-air BUK missile system that shot down MH17.

Conclusion

Five factors explain Russia’s actions in 2014. The first factor emerged in the decade prior to the 2014 crisis with the rehabilitation of Tsarist Russian and White émigré nationalist (imperialist) views of Ukraine and Ukrainians, and Putin’s view of himself as the ‘gatherer of Russian lands.’ The second and third factors are inter-connected. Putin’s personal anger at being humiliated for a second time by a western-backed Ukrainian revolution undermined his ‘gathering of Russian lands’ that would have turned Ukraine away from the EU and toward the Russian World and Eurasian Economic Union. The fourth factor is Russia’s long-standing territorial claims against Crimea going back to the early 1990s. The final factor is the Lukyanov Doctrine’s view of Ukraine as possessing limited sovereignty, which is a product of both the Soviet-era Brezhnev Doctrine and the first point; namely, Ukraine being perceived as an artificial state.

Russia’s ‘full spectrum conflict’ began following the Orange Revolution and continued through to 2013. Between 2012–2013, Russia launched a massive trade, intelligence, cyber, and informational operation to pressure Ukrainian leaders to drop EU integration. In the decade prior and in 2014, pro-Russian extremists were given paramilitary training, and Russian intelligence infiltrated Ukrainian security forces, especially in Crimea. With a high level of infiltration, it is unsurprising that Russian intelligence was active on the ground in Ukraine between 2013–2014 during the Euromaidan and after Yanukovych fled Kyiv. Russian spetsnaz soldiers intervened in mainland Ukraine from occupied Crimea and, with the assistance of Russian nationalists (imperialists) and political tourists trained in Russia and bussed into Ukraine, transformed protestors into armed insurgents. Pro-Russian Chechen proxies were sent by Kadyrov. Russian information warfare was placed on a war footing. Military equipment was supplied throughout 2014, from June of that year, artillery attacks were taking place from Russia into Ukraine, and Russia invaded Ukraine on Ukrainian Independence Day (24 August). Taken together, these different aspects of Russian ‘full spectrum conflict’ constituted Russian intervention from the first day of the 2014 crisis. Western scholars should place greater trust in the Ukrainian public, which has never seen evidence of a ‘civil war’ in Ukraine. The impact of the full range of Russian ‘full spectrum conflict’ was the opposite to that which Putin sought, and three areas of which are analysed in the concluding chapter. Putin’s policies towards Ukraine undermined a pro-Russian ‘east’ and the Soviet concept of Russian-Ukrainian ‘brotherly’ peoples, thereby increasing Ukrainian civic national integration and severely curtailing Russian soft power in Ukraine. Putin’s inability to comprehend his mistakes in these three areas and his longevity in power for another sixteen years make the chances for peace low.

[2] Igor Girkin interviewed by Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye, 23 August 2019.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Putin’s Obsession with Ukraine as a ‘Russian Land’

- Vladimir Putin’s Imperialism and Military Goals Against Ukraine

- Opinion – The Rationale of Russia’s ‘Special Military Operation’ in Ukraine

- Opinion – Russia’s Choices in Ukraine

- Opinion – On and Beyond Whataboutism in the Russia-Ukraine War

- New Book – Crisis in Russian Studies? Nationalism (Imperialism), Racism and War