It was not long after 2020 began that citizens world-wide realized it would be marked by COVID-19. Following the declaration of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on January 30th, 2020 by the World Health Organization (WHO), the COVID-19 outbreak was further declared a pandemic on March 11th, 2020, 12 days before the United Kingdom’s (UK) Prime Minister Boris Johnson put the country under a lockdown. As lockdown progressed, people tried to come to terms with the realities of the situation. A worrying trend, though, came to light in the weeks that followed the UK’s lockdown: people from certain UK communities, namely from BAME (Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic) communities, seemed to be more at risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19. Despite these communities making up 14 percent of the population, 35 percent of 2000 intensive-care unit beds were occupied by people from BAME communities.[1]

This research does not focus on this phenomenon, however. I state it here to describe how I chose to embark on the research journey of this paper. The insights with regards to the BAME communities and COVID-19 point to a larger set of questions arising in the current PHEIC. How do marginalized communities and the government interact in such a situation and what are the government’s duties?

I chose to take my analysis to the international level and look at the most recent and most similar experience of a PHEIC: the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, occurring from 2013 to 2016. What I found was that indeed the relationships between citizens from a part of the world marginalized economically, socially and politically in the international community; the political leaders of West Africa; and international actors offered bountiful fodder for analysis.

I outlined my universe of cases as the three most-affected nations in West Africa, namely Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia and began to study them in-depth. Indeed, some research exists which has already begun to understand the interactions of these three types of actors during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Research focusing on the relationship between West African citizens and their governments has analysed how perceptions of government capacity performed during Ebola. For example, Nuriddin et al. (2018) point to the positive correlation between the capacity of governmental health care services during the 2015 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone and community trust. Furthermore, a greater body of literature has begun analysing perceptions of West Africans, particularly citizens, during the Ebola crisis. For example, the work of Ali et al. (2015) argues that the Western world’s characterization of Ebola-ridden countries was strongly infected with racist tropes and served to stigmatize West Africans.[2] In a particularly telling passage, Ali et al. write:

In this type of colonialist discourse, “other” parts of the world are depicted as dangerous, particularly those with “warm climates” from where “new and emerging diseases” are seen to emanate in the twenty-first century.[3]

However, although research has begun analysing the roles of principals and agents during a PHEIC in a developing context, the research on West Africa and its intra- and inter-state relations during Ebola remains fundamentally sparse, perhaps marred by the lack of data on this region. That is why I formulate my three research questions as follow:

First Research Question: Did the Liberian public’s trust in their President and Parliament (Y variable) decrease or increase as new cases of Ebola (X variable) sprung up in the 2011 to 2018 period?[4]

Second Research Question: How did the Liberian government address its citizens and during the 2014 to 2016 Ebola crisis?

Third Research Question: How did the international community view Liberian leaders and citizens during the Ebola crisis?

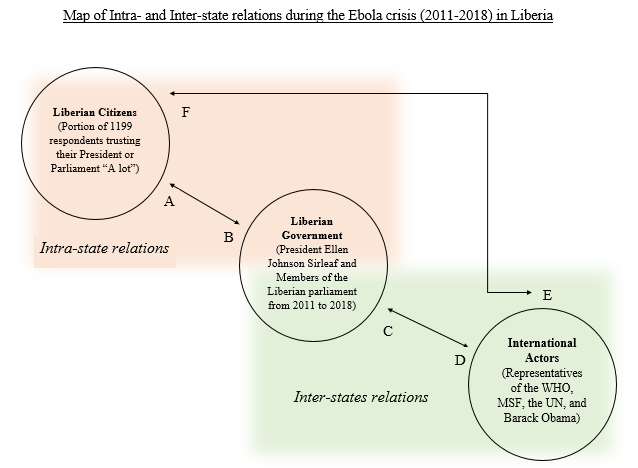

I choose to answer these questions because they help us understand the structure of principal-agent dynamics as illustrated in Figure 1. The data I chose to analyse was primarily chosen based on availability. Since the perception of the Liberian government by the Liberian citizens is quantifiable, I operate with that data. The other relationships cannot be supported by quantifiable data; thus I choose to look at qualitative data. In Figure 1, the overall picture of this research is presented. I aim to explore relationships A, B, C, and F with past literature supporting knowledge about relationships B, C and F. Much more work remains to be done to understand the workings of each relationship flow, especially E.

Applying regression analysis and discourse analysis to quantitative and qualitative data, namely Afrobarometer survey data from three survey rounds spanning years from 2011 to 2018 and approximately 40 pages of speeches from Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, Doctor Margaret Chan, Doctor Joanne Liu, Barack Obama, and David Nabarro, I find that:

First Argument: There is a clear negative correlation between Liberian public trust in their President and Parliament and the number of new Ebola cases rising. Specifically, for every one Ebola case, the proportion of the Liberian public trusting their President “A lot” decreases by 0.0039 persons while the proportion trusting their Parliament “A lot” decreases by 0.0029 persons.

Second Argument: The Liberian state sought to justify its actions vis-à-vis the Liberian public as public trust was decreasing while the international community painted Liberia as incapable of controlling Ebola.

Third Argument: International actors ultimately perpetuated an image of the Liberian state as without agency, authority, or sovereignty and thus in need of saving by Western-influenced international actors. Furthermore, Liberian citizens were constructed as “noble savages” by these same international actors.

Before presenting the literature associated with this topic, the research design, my findings and further discussions and conclusion, I briefly provide background knowledge of the context of Liberia, Ebola and the international actors involved.

Present-day Liberia was founded in 1822 as a colony of the United States of America. Liberia was founded by the American Colonization Society which was formed in the United States (US) in 1816 with the purpose of colonizing a place for free-born Black Americans and former slaves to reside. On July 26, 1847, Liberia declared its independence from the United States, beginning a long history of political and economic domination by its American colonizers, despite having been inhabited by differing ethnic groups for at least a millennium. The Americo-Liberians, constituting only two percent of the population, made up nearly 100 percent of voters, and voted in one party, the True Whig Party, from the 1860s to the 1960s. On April 12, 1980, Master Sergeant Samuel K. Doe overthrew the President, William Tolbert, and instituted a military dictatorship which lasted until 1989 when several different factions vied for the country’s leadership after the loss of US support. After the invasion of Liberia by Americo-Liberian Charles Taylor and his National Patriotic Front in 1989 and the 1990 assassination of Doe, a seven-year-long civil war ensued which ended with a peace agreement and the 1997 election win by Taylor. However, by 2001, two rebel groups began warring with Taylor’s government forces and a new, three-year-long civil war began. The war ended at a peace summit in Ghana in 2002, when the organization Women of Liberia, Mass Action for Peace salvaged talks that had failed between Taylor and the two rebel groups. In 2005, one of the leaders of WLMAP, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf began what would be a 12-year long tenure as Liberia’s President and Africa’s first female head of state. Sirleaf led the country through the Ebola crisis which began in Liberia in Foya on March 30, 2014. With the peak of the outbreak occurring in August and September 2014 and 42 days of no-transmission finally having passed in June 2016, Ebola had left Liberia having killed approximately 4810 people. The Ebola outbreak in Liberia warranted a wide-ranging global response, including major efforts by the United Nations Mission for Ebola Emergency Response (UNMEER), the WHO, Médecins sans Frontières, and individual governments such as Cuba and Germany.

I. Literature Review

Principal-Agent Theory

Inspired by the work of Kamradt-Scott (2016) which judges the WHO’s actions during the Ebola outbreak considering its position as an agent of principal nation states, this work rests on Principal-Agent Theory, as applied to intra- and inter-state relations. Hawkins et al. (2006) provide a definition of Principal-Agent Theory from which I profit: “The relations between a principal and an agent are always governed by a contract […] To be a principal, an actor must be able to both grant authority and rescind it”.[5] The set-up of Principal-Agent Theory, in which one actor, the principal, authorizes (through a contract) another actor, an agent, to represent their best interests or act on their behalf, lends itself well to analysing the relations between citizens and those they elected to government and between states and international actors. This is because in a principal-agent setup an essential delegation of interests exists which can potentially go wrong. I do not here analyse what went wrong nor why, let alone frame such an analysis referring to the typical information asymmetries resulting from the Principal-Agent problem (moral hazard and adverse selection), opting instead to quantify and visualize that relationship as embodied between Liberian citizens and their politicians at a certain point in time, and how international agents may view these Liberian principals (the citizens).

Public Trust

When speaking of public trust, scholars most often refer to it in the framework of the public trust doctrine which refers to the fact that certain natural and cultural goods are protected, by the government, for public use.[6]

Relatedly, there exists also the concept of the public trust, which is an organization managing resources for not-for-profits or other organizations serving citizens in need.[7]

However, the concept of trust analysed here is different. It is related to the trust which the Liberian citizenry has in its democratic institutions. Such a concept can be traced back to the fourth century BCE in Thucydides’ account of the Mytilenean Debate. In a recent trend, scholars of political science have worked to benefit from the contributions of classical works in defining trust. Thus, Mara (2001) writes that Thucydides’ account points to the need for building trust amongst the citizens towards rulers precisely in order to build solidarity in overcoming moments of weakness in acquiring the common good.

The pursuit of defining public trust is further complicated by the issue of causality. Namely, pre-existing or current perceptions may taint the extent to which government performance impacts citizens’ trust. Van de Waale and Bouckaert (2011) write on this issue and conclude that, “actual performance is not equal to perceived performance”.[8] This is an important methodological consideration but implementing its findings into research design is beyond the breadth of this study.

Thus, I opt to focus on a more narrow aspect of public trust. Perhaps the most famous analysis of trust in social science has been Robert D. Putnam’s Theory of Social Capital. Putnam’s thesis is that high levels of social trust (as a social value) at the aggregate level, combined with specific norms and plentiful networks, leads to a “high level of political integration”.[9] Although flawed by logical circularity (social capital is simultaneously a cause and an effect), Putnam’s input is worthwhile for flagging the connection between public trust and its connections and potential impacts on political and democratic success.

For the purposes of this research, I opt for a definition offered by Gambetta (1998):

Trust […] is a particular level of the subjective probability with which an agent assesses that another agent or group of agents will perform a particular action, both before he can monitor such action (or independently of his capacity ever to be able to monitor it) and in a context in which it affects his own action.[10]

This succinct definition captures what I imagine public trust to be on the individual basis. I adopt this definition and pool it to the aggregate, showcasing what the Liberian public’s trust is as a relationship vis-à-vis the Liberian government.

Public Trust in Liberia

Theoretically, the concept of public trust in literature focusing on Liberia, or even Western Africa for that matter, remained relatively scant until the mid to late 2000s, after warring had ceased in 2003-2004. Thus, most of the literature not focusing on the relationship between public trust and Ebola focuses on the struggle to (re-)build public trust after the Liberian civil wars. The topics which are most often addressed are security sector reforms, corruption and state finances.

Sherif and Maina (2013) critically assess the government’s provision of decentralised security and justice services through the creation of regional hubs. The author argues that the hub model “bears promise”, but that it “hinges on the ability of the state to […] regain the trust of its citizens”.[11]

When critically assessing the drawdown of UNMIL, Podder (2013) argues that including local actors in security sector reform is crucial not only to the success of the reforms but for public satisfaction overall. Podder writes that, “efforts remain disengaged with the public perception […] This oversight has to be rectified to minimize negative impacts of security transition […]”[12]

Whilst highlighting the importance of public trust in ensuring state stability and consolidation, Karim (2017) offers two new criteria for “assessing security sector reforms’ effect on confidence in the security sector […]”[13] Her criteria of restraint and inclusiveness more specifically translate into policies which include females in the security sector.

Beekman, Bulte and Nillesen (2014) try to measure the willingness to contribute to public goods as perceived corruption increases. They conclude that, “corrupt leadership attenuates […] investment incentives”.[14]

Finally, Gujadhur (2011) analyses the lessons learnt in Liberia in efforts to implement economic governance reforms while also building public trust in the 2006 to 2011 period. He takes Liberia to be a success story in this respect, arguing that despite the colossal financial constraints faced by the Sirleaf administration as a result of the civil wars, a balance between international and local interests was struck to the benefit of the country.

Public Trust and Ebola

Two broad categories, including attention paid to local responses and inclusion in wider treatment programmes and the causal relationship between trust, fear, and (non-)compliance, govern the literature on public trust and Ebola.

Much of the literature generally focuses on necessary reforms for future PHEICs. For example, Kruk et al. (2015) point to the relationship between resilient health-care systems and the government’s capacity to contain fear when emergencies strike. More specifically, resilient health care systems, claim the authors, are more adept at containing fearful reactions of the public.

Bemah et al. (2019), point to the specificities of training programmes and analyse which are more productive in properly training local staff in administering safe and quality services (SQSs) in Ebola treatment units (ETUs). They argue that local health care staff must receive refresher training in order to increase emergency preparedness.

However, aspects of the Liberian response have been praised. When studying the local hospitals’ situation reports, Fallah, Dahn and Nyenswah (2016) argue that community-based initiatives (CBIs) were critical in cutting the transmission chain of Ebola, a feat done earlier than its two neighbours Sierra Leone and Guinea, both of which have a higher per capita GDP than Liberia.

The research of Barker et al. (2020) takes Fallah, Dahn and Nyenswah’s research a step further. Barker et al. argue that although it may be clear that local community empowerment in public health emergency responses is crucial, it is still not clear which mode of facilitation of community-centred approaches works. Thus, the researchers test which forms of community engagement (CE) had a meaningful impact and found that approaches which treat local communities as active agents in the response rather than as passive receivers of health services offered the highest success rate. Thus, policies such as initiating community-based surveillance teams increased trust in health authorities” which “facilitated health system response efforts” all “leading to a fortuitous cycle”.[15]

The 2020 paper by Blair, Morse, Tsai tested the effectiveness of the Liberian government’s door-to-door canvassing campaign from 2014 to 2015 and found that it was more effective when local intermediaries implemented it as they were then subject to “monitoring and sanctioning”, thus making them seem “more accountable and credible”.[16]

Vinck et al. (2018) test the effect of low trust in government on Ebola beliefs and subsequent practises. They find that “low institutional trust [is] associated with a decreased likelihood of adopting preventive behaviours”, whilst acknowledging that over a quarter of their respondents did not believe the outbreak was real.[17]

Blair, Morse and Tsai (2016) have been monumental in the field of connecting public trust to governmental responses in public health emergencies. They test if a correlation exists between trust in authorities and compliance with Ebola-control measures. They found that even when respondents were fully aware of how Ebola is transmitted and what should be done to lower the risk of transmission, their indication of low trust in authorities still pushed them to not comply with control measures. Whilst other papers have showcased the importance of trust as a variable, this paper strongly argues for trust as a central determinant in anti-transmission practises.

Within this category, there is also a sub-category of micro literature focusing on effects after the Ebola pandemic in Liberia.

The work of Morse et al. (2016) analyses the impact that demand-side factors such as trust and negative health care experiences during the Ebola outbreak have on demand for health care after the pandemic. They find that distrust of authorities and a negative Ebola-related experience decreases health-care utilisation whilst government-organised community outreach programs increase it.

Elston et al. (2016) similarly assess the impact on health care authorities after the pandemic. They argue that the relationship between fear, trust and use of social services ran in a circular fashion, i.e. fear of Ebola and health care workers caused a decrease in trust of the public health care system and thus a decrease in use of it which in turn caused a greater fear of Ebola. The authors argue that this caused a further decrease in “community cohesion”.[18]

While recognizing the effect that the public’s distrust of the government has had on the success of Ebola containment, Woskie and Fallah (2019) aim to assess the effect of distrust of the government by the public on the provision of universal healthcare coverage (UHC) also post-pandemic. They note that a distrust of authorities continues post-pandemic and hampers efforts to institutionalize UHC.

Finally, in the ground-breaking book Politics of Fear (2017), former Médecins sans Frontières staff member Mit Philips recounts lessons learned during the pandemic, and notes that tense “interpersonal relationships between the healthcare authorities, healthcare workers, and the general population” caused a reduction in demand for health care.[19]

The International Community and its Ebola Response

The research of Abramowitz et al. (2017) showcases that local communities can rapidly reverse the pattern of thought and action that they harbour vis-à-vis diseases such as Ebola, especially in a climate of increasing mortality rates. The authors state that, “Global public health response […] should draw upon […] our most significant finding […] Ebola behaviour change messages were only adopted and maintained when they were seen as “realistic” or “practical” in daily life”.[20] It is notable that the authors refer immediately to the international response effort, without offering suggestions for state-centred approaches. This is potentially at odds with research such as that from Kucharski and Piot (2014) who argue forcibly for the need for a global response: “The scale of the current outbreak means an international response is needed”.[21] They state that “the international community must commit the resources required to control the outbreak”, such as “expertise and equipment, […] financial support, […] experienced healthcare workers[,] […] additional protective clothing and isolation units”, amongst others.[22]

Woldemariam and di Giacomo (2016) argue against several measures posed by the international community to try and alleviate the Ebola crisis in Western Africa. They argue, for example, that “campaigns to educate and raise funds for Ebola and Africa […] would have proved more effective if Africa had been represented in its many facets […] rather than as a perpetual single victim”.[23]

Following this strain of thought, authors have argued that the Liberian state was seen as incapable of controlling the virus primarily because it was an African state. This, they argue, is evidenced by the scientifically unjustified actions on the part of states and international organizations. For example, Tejpar and Hoffman (2017) argue that the travel restrictions instituted by Canada, alongside several other countries, were illegal as they did not abide by the WHO’s International Health Regulations (IHR).

Roemer-Mahler and Rushton (2016) spend considerable space criticizing the “securitization” of Ebola.[24] The authors argue that the international community only saw Ebola as a security issue and not one concerning public health. Furthermore, it was not until the health of Western nations was endangered that global leaders amplified their response. Furman (2017), moreover, brings attention to the fact that two U.S. healthcare workers and a Spanish priest were the first to receive an experimental Ebola treatment. Moreover, Furman criticizes that an ethics panel which the WHO convened had no Africans present in it.

Southall, DeYoung, and Harris (2017) argue that because of Liberians’ mistrust in authorities both at the national and international level and “the lack of cultural competency”, local efforts to effectively respond to Liberia were ignored and international cooperation with these efforts was absent.[25]

There is a rich literature discussing and criticizing the global response to Ebola and, more generally, the outlook this community has on Ebola and the Africans involved in it.

Monson (2017) argues that mainstream news and social media in the United States (US) during 2014 engaged in an “othering process” in which it “reproduced and perpetuated the Ebola-is-African, Ebola-is-all-over-Africa, and Africa-is-a-country narratives”.[26]

Ali et al. (2016) argue that the “colonial legacy” of Westerners “fan[s] the flames of fear” as it produces a “social amplification of risk”. The colonial legacy has this role, the authors argue, as it prompts a vision of “Africa as a site of primitivism and catastrophe” and encourages “colonial discourses of backwardness, exoticism and savagery”.[27]

Finally, Kingsbury’s (2015) work engages directly with media representations of Western efforts to curb Ebola in Liberia. She argues that ultimately the Western view “serves primarily to reinforce paternal relationships […] and a societal perception that ‘we’ are the saviours”.[28] Trckova (2015), moreover, argues that the representation in US newspapers of Ebola’s victims painted them as “voiceless” and “agentless”, or as “fail[ing] to represent infected ordinary Africans as sovereign agents”.[29]

Positioning this Research

This research attempts to enter the conversations outlined above by constructing a picture of principal-agent relations which aims to understand the role of these three actors in their rights and responsibilities to each other but also their perceptions of Self and the Other by further engaging with themes of public trust and Western supremacy. This snapshot is lacking and represents the primary and essential gap in the literature. Less generally, this research aims to contribute to the existing literature by quantifying and visualizing the relationship of public trust in Liberia during a PHEIC, connecting public trust in its government to the visions of international agents, and critically analysing the speech products of these international agents.

II. Data and Methodology

Case study

Firstly, it is imperative to delineate what exactly a case study is. I operate with Gerring’s (2006) definition:

Case connotes a spatially delineated phenomenon (a unit) observed […] over some period of time. It comprises the type of phenomenon that an inference attempts to explain.[30]

Thus, as Gerring points out, a case study consists of a unit which the research studies in depth to reach observations about the phenomenon itself, its characteristics etc.

When studying Ebola in Africa during its most recent outbreak (from 2014 to 2016), the universe of cases from which to choose include Nigeria, Mali, and Senegal, alongside the worst-affected countries in West Africa, including Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone.

The process of selecting one case to study considered the various and congruent factors of the countries, such as demographic makeup, economic strength, and the effect Ebola had on the country. In choosing a case best fitted to answer the research questions and which would not be hindered by the numerous different variables amongst the universe of cases, Liberia was chosen as a paradigmatic case. A paradigmatic case is “an exemplar”, a case emblematic of an event but one which does not necessarily share typical characteristics with other similar cases.[31]

This research does not aim to offer causal claims with the data analysed. To answer the research questions, a ‘Mixed methods’ approach, i.e. one which “collect[s] and analyse[s] both quantitative and qualitative data within the same study” is adopted as the research questions inspire this approach.[32] The quantitative data and analysis is employed to obtain a clear and reliable visualization of the relationship between Ebola cases in Liberia and public trust, while the qualitative data and analysis was employed to discover the images of fellow international actors that each respective actor under analysis created. The answers will be considered sufficient once the analysis has come out from the data exploration with a clear negative or positive correlation between the two variables in the first research question, and a rich set of themes (at least five) to answer the last two research questions.

Data

The quantitative data is from Afrobarometer’s online database of survey rounds and from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). I look at three survey rounds (2011-2013, 2014-2015, and 2016-2018) from Afrobarometer to get as robust a picture as possible, combining it with the number of new cases rising in Liberia from 2014 to 2016. I choose two specific survey questions and plot the percentage of people responding (the average number of respondents being 1199) with a trust level of “A lot” to these three questions:

Survey Question 1: How much do you trust each of the following, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say: The President?

Survey Question 2: How much do you trust each of the following, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say: Parliament?

I choose the President and Parliament because these were the two most powerful and active governmental respondents in Liberia’s Ebola experience. Survey questions do present the potential for biased answers, perhaps by pushing the respondents to answer in a certain way. However, of the data available, I judge this data to be the closest approximation of subjective attitudes of trust in Liberia. Moreover, the questions have not been stated in a suggestive way.

The qualitative data consists of publicly-available speeches by Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (President of Liberia from 2006 to 2018), Doctor Margaret Chan (Director-General of the WHO from 2006 to 2017), Doctor Joanne Liu (International President of MSF from 2013 to 2019), Barack Obama (President of the US from 2009 to 2017), and David Nabarro (Special Envoy of the UN Secretary General on Ebola from 2014 to 2015). This readily-available data indicates the utterances regarding the Ebola catastrophe in Liberia of the leading relevant political figures of the time. I apply discourse analysis to approximately 40 pages of text, equalling around 13,400 words.

Quantitative Analysis

In this research, I use quantitative data and analysis as a point of departure for a more intriguing, qualitative analysis. The quantitative analysis serves to understand the “social cognition”, or the “public mind”.[33] More specifically, the quantitative analysis is more so directed towards achieving insight, which is “the product of a good case study”.[34] Finally, the survey data is used to capture the subjective nature of perceptions of trust, following Gambetta’s definition.

I first systematized the data in Excel to prepare it for import into RStudio by aligning the evolution of the number of new cases and the survey responses to the same time frame.

I then imported the data into RStudio, after which I coded for a regression model and visualized this model by creating a LOESS regression image to more flexibly indicate the relationship between the number of new Ebola cases in Liberia and the number of respondents trusting the respective governmental institution “A lot”.

Qualitative Analysis

Foucault states that power is claimed through discourse, stating, “Discourse […] is the thing for which there is struggle, discourse is the power which is to be seized”.[35] With this in mind, an analysis of the discourse around Ebola by the world’s leaders can potentially lay bare relations of power in the setting studied.

I employ van Dijk’s critical discourse analysis as it lends itself most formidably to the nature of my research questions. Assuming, in the essence of Foucault and van Dijk, that discourse is the terrain for power-making and power-taking, van Dijk advises discourse analysts to approach the text with the following question in mind: [What is] the role of discourse in the (re)production and challenge of dominance?[36] Thus, I analyse the official speeches of world leaders to engage more directly with power-making through discourse, and, quite specifically, with the potential transgressions against democratic values. As van Dijk puts it:

Critical discourse analysis is specifically interested in power abuse, that is, in breaches of laws, rules and principles of democracy, equality and justice by those who wield power.[37]

I performed my discourse analysis in ATLAS.ti, a software which allowed me to code for the main themes arising out of the texts. Searching for themes meant critically assessing, in an inductive fashion, speeches for ways in which actors worked to perpetuate or vivify their positions of power.

Ethical Considerations

This project did not require ethical approval, but it requires ethical consideration. I keep in mind Mama’s (2007) proclamation that, “For Africans, ethical scholarship is socially responsible scholarship that supports freedom […]”[38] My aim is to be aware of my positionality as a white, middle-class woman who has never visited the country she is studying. I aim to do more good than harm, which is one of the reasons I chose critical discourse analysis. I attempt to take the viewpoint of those most disadvantaged.

III. Findings

A. Quantitative Analysis – Relationship B

As a point of departure, this research seeks to quantitatively understand the relationship between the Liberian public’s trust in its governmental institutions and the number of new Ebola cases rising in that country.

Thus, a regression analysis of the relationship between the amount of respondents (the principals) trusting a certain governmental institution (the agent) “A lot” and the number of new Ebola cases provides the following results.

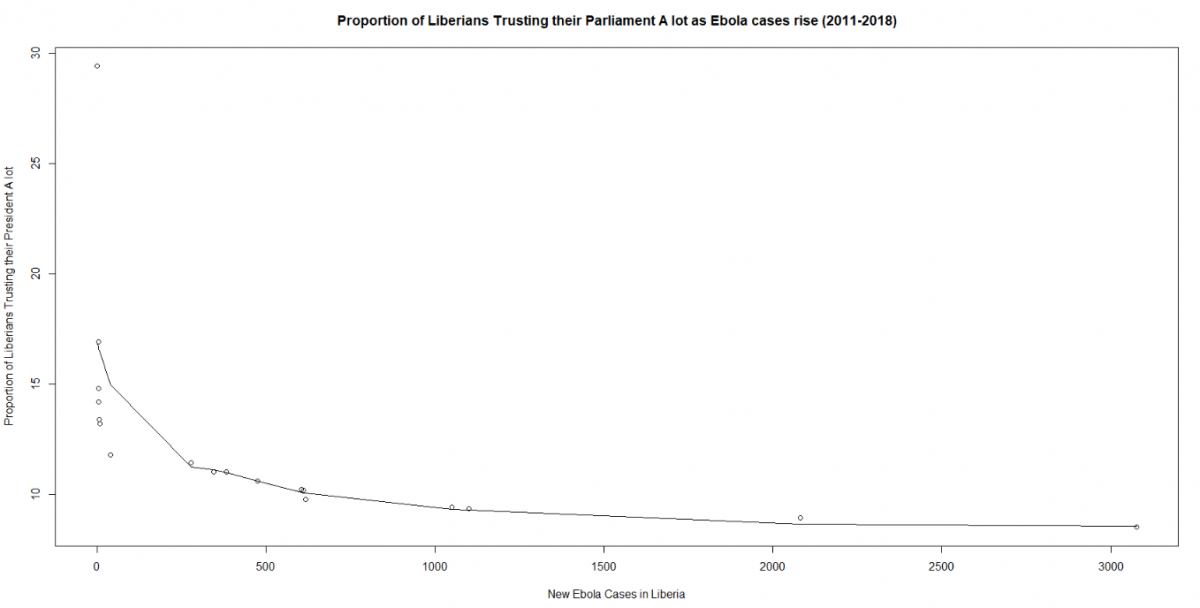

When analysing the effect the number of new Ebola cases (here coded as “new_cases”) has on the amount of Liberian survey respondents trusting the President “A lot”, the following results were obtained:

| ESTIMATE | STANDARD ERROR | t-VALUE | PR ( > | t | ) | |

| INTERCEPT | 22.1721 | 1.1261 | 19.689 | 1.22e-12 |

| new_cases | -0.0039 | 0.0011 | -3.437 | 0.0033 |

The regression analysis indicates that with the rise of one Ebola case the number of respondents trusting the President “A lot” decreases, on average, by 0.0039 people. We can also visualize these results graphically in Figure 2.

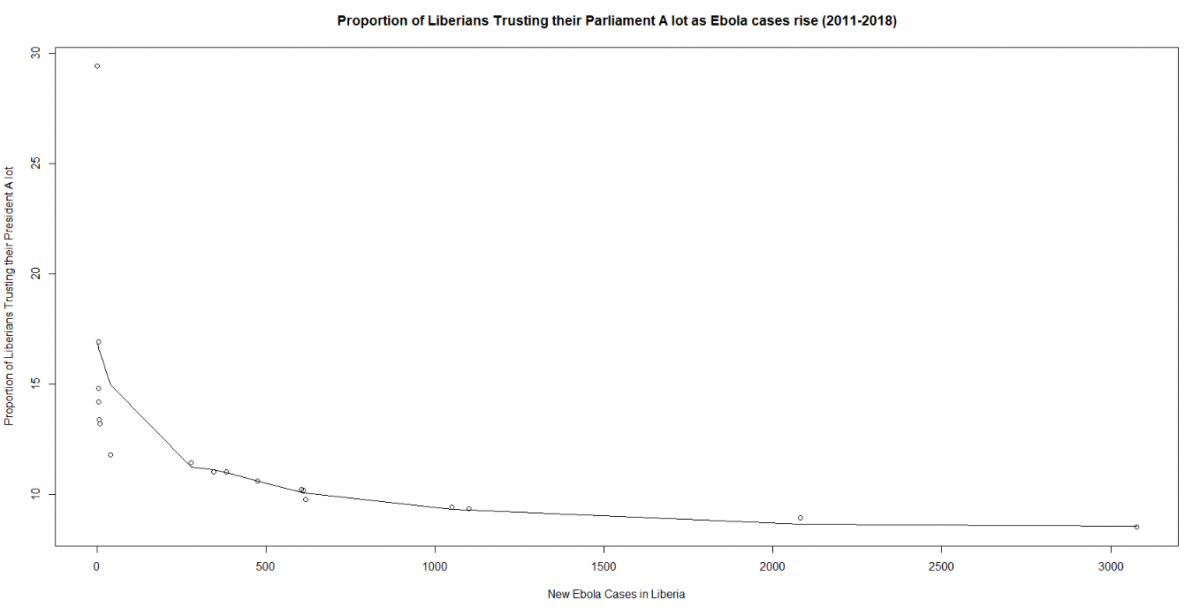

This quantitative analysis can also be executed to study the effect that the number of new Ebola cases had on the proportion of Liberians responding that they trust their Parliament “A lot”. The results of that regression analysis are as follows.

| ESTIMATE | STANDARD ERROR | t-VALUE | PR ( > | t | ) | |

| INTERCEPT | 14.1406 | 1.2664 | 11.17 | 5.8e-09*** |

| new_cases | -0.0029 | 0.0013 | -2.24 | 0.0396* |

According to the regression analysis, an increase of one Ebola case in Liberia during the outbreak decreased, on average, the proportion of Liberians trusting their Parliament “A lot” by about 0.0029 people. As a graph, this relationship is visualized in the following manner.

The results showcase that during Ebola a lower proportion of people trust their democratic institutions “A lot” as these same institutions were on the defence trying to bolster limited capacities in the fight against Ebola. The quantitative analysis does not point to any causal conclusions. This could be for a variety of reasons, including a potential presence of confounding variables. For example, perhaps the decline in the number of people trusting their President or Parliament “A lot” is due to another event besides Ebola. Moreover, although there is a clear correlation, the size of the correlation coefficient is not particularly strong, thus more in-depth quantitative analysis is called for. The results may, however, predict similar scenarios as Liberia presents a paradigmatic case, such as the COVID-19 experience in Somalia.

B. Qualitative analysis – Relationships A, C, and F

Construction of Liberia as an Incapable State

I argue that the Liberian government (the agent) adopted a rhetoric of justification in respect to its actions against Ebola when addressing Liberians (the principals). The international community, who adopts the agent position in its relationship with Liberia, created an image of an incapacitated state.

Throughout the Ebola crisis, President Sirleaf established a pattern of justifying the Liberian government’s actions. In the beginning of a June 2014 speech made amidst rising Ebola cases, Sirleaf states, “The Government of Liberia and Partners has done this much”.[39] In a bid to justify what her government has been doing, Sirleaf goes on to list three actions which her government has taken to help curb Ebola.

In a July 2014 statement, the President spent nearly the entirety of her speech outlining the actions which the government had taken against the Ebola virus. In particular, the President outlines the creation of the National Task Force, the sole authority for responding to the Ebola virus. The President does not outline how the Force will be funded, and indeed speculations were later brought about that since there was limited transparency on the Force’s functioning, potential corruption ensued.

Instead Sirleaf jumps to the impact Ebola had on government institutions. Sirleaf states, “Obviously, this dreadful virus has overtasked our public health facilities and capabilities”.[40] The word “obviously” here works to eliminate criticism that it was the government’s (in)action against Ebola and not Ebola itself that overtasked public health institutions. The use of the word “dreadful” has a similar function, attempting to convince the listener that the government understandably been overtasked by a virus so monumental that even the government’s best efforts could not have helped curb Ebola.

In a September 2014 statement made as the number of new cases was now reaching its peak in Liberia, Sirleaf described her government’s fight against Ebola as a fight against a virus which “not even the world’s experts knew” was Ebola.[41] By creating an image of Ebola as an unknown, mysterious virus, Sirleaf works to elicit sympathy from listeners since any failing in answering an unknown disease could be understandable. Tellingly, Sirleaf states that, “With limited resources and capacity, the government responded swiftly and decisively to the outbreak”.[42] The President here aims to present her government’s actions as symmetric to the scale of the Ebola disaster, reminding us that the actions were with a handicap, namely that of a lack of resources and capacity. Finally, at the end of the speech, Sirleaf reminds listeners that, “We acted within the scale of our capacity to contain the scale of [sic] an outbreak we could not imagine possible”.[43]

Finally, in October 2014 at the World Bank, Sirleaf positioned Ebola as the reason for her government’s stalling on the successes which Sirleaf claims her government achieved vis-à-vis their development agenda. She further claims that any faults in her government’s response to Ebola are not caused by her government: “With limited understanding of the disease, low human capacity and a slow international response – the disease quickly outpaced our ability to contain it”.[44] Sirleaf here also indicates that responsibility for the disease outpacing any government containment efforts rests also with the inaction of the international community.

This research does not suggest that Sirleaf should not have justified her actions or that she did not make understandable statements, but rather aims to look at what rhetoric Liberia, as a paradigmatic developing state, adopts during a PHEIC; it is one of justification.

The international community, meanwhile, worked to create an image of Liberia (and West Africa as a whole) as incapable of answering to the crisis. For example, Barack Obama ignored any state-led attempts at alleviating the crisis and instead simply stated, at the United Nations in September 2014, “In Liberia, in Guinea, in Sierra Leone, public health systems have collapsed”.[45]

Another example arises from Doctor Margaret Chan March 2015 speech:

Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone are among the poorest countries in the world. At the start of the outbreak, all three had only recently emerged from years of civil war and unrest that left basic health infrastructures damaged or destroyed and created a cohort of young adults with little or no education.[46]

Chan again called these three countries the “poorest and least prepared countries on Earth” at her November 2nd, 2015 address at the Princeton-Fung Global Forum. Chan thus creates an image of Liberia as an incapacitated state. Instead of acknowledging what the government had done, Chan chooses instead to paint, through a Western gaze, a stereotypical picture of Liberia as a place ravaged by war, poverty and a lack of education. She furthermore ignores the specificities of Western African nations, such as the fact that their GDPs, although amongst the lowest 50 of the world at the time, nonetheless differed (their 2016 GDPs in USD measured seven, four, and two billion for Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, respectively).[47]

Construction of International Actors as Saviours

I argue that international actors securitized Ebola as a global issue, formulating a public health crisis in Liberia and its neighbouring states as a threat to international security. Moreover, they regarded Liberia as incapable of controlling Ebola, thus denying the Liberian state its agency and authority. Finally, international actors positioned themselves as the saviours of Liberia from its incapacity to control Ebola and thus saviours of the world, even denying Liberia’s sovereignty by doing so.

In his September 2014 UN speech, Obama denied the Liberian state its agency and authority by securitizing Ebola, after which he worked to posit the United States as the sole, unquestioned saviour of the region and the world from Ebola’s threat. At the very beginning of the speech, Obama frames Ebola as “an urgent threat to the people of West Africa, but also a potential threat to the world”.[48] Obama thus sees Ebola more than just a health crisis in West Africa; he sees it as a potential threat to his own nation thus signalling that Ebola is of importance to him only as a security threat. Obama continues to align Ebola as an international security issue which West Africa is incapable of taking care of when he says, “[…] this is also more than a health crisis[,] [it] is a growing threat to regional and global security.”[49] It is at this point that Obama has already constructed West Africa and thus Liberia as a country without authority in the international stage as it is incapable of controlling a virus which may pose a threat to the world. It was at this point that the international community stepped in to act, not while the PHEIC was more localized in West Africa.[50]

Responding to an incapable Liberia, Obama proceeds to position the United States as the sole, unquestioned leader on the world stage, bringing material aid and expertise only it can provide:

Last week, I visited the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is mounting the largest international response in its history. I said that the world could count on America to lead, and that we will provide the capabilities that only we have, and mobilize the world the way we have done in the past in crises of similar magnitude. And I announced that, in addition to the civilian response, the United States would establish a military command in Liberia to support civilian efforts across the region.[51]

Obama highlights his own actions predominantly in this statement, and those of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a public health institute in the United States. Nowhere does he mention what West African leaders have done, policies which they have proposed, or aid they have requested.

Finally, Obama announces the US’s plan to set up a military command in Liberia, ignoring questions of respect for Liberian sovereignty and the existence of UNMIL in Liberia already, or any actions they may have taken.

Throughout her September 2014 UN speech, Liu created an image which proposed that MSF was the only actor appealing for international help, denying agency, authority, and sovereignty to Liberia. For example, Liu states, “I am forced to reiterate the appeal I made two weeks ago. We need you on the ground”.[52] Liu ignores the existence of consistent pleas for international help from several West African leaders and Sirleaf in particular. Moreover, Liu repeatedly brought up the actions MSF was undertaking and framed her organization as the actor commissioning the greatest effort in the Ebola response.

As of today, MSF has sent more than 420 tonnes of supplies to the affected countries. We have 2,000 staff on the ground. We manage more than 530 beds in five different Ebola care centres. Yet we are overwhelmed. We are honestly at a loss as to how a single, private NGO is providing the bulk of isolation units and beds.[53]

Liu does not acknowledge the actions of locals or the state, or the fact that MSF had become a main responder only after government health institutions reached breaking point.

Construction of Liberian Citizens as Primeval

Finally, I argue that world leaders created an exotified image of Liberians (who are, in relation to them, principals) as “noble savages” and Liberia as being the antithesis of modern.

This is perhaps most potently manifest in the speeches of Doctor Margaret Chan. In her March 2015 speech, Chan began by characterizing Ebola as an “exotic pathogen”.[54] Why would Ebola be an exotic pathogen? If one is to employ the dictionary definition of exotic, then Ebola, a disease not unknown nor mysterious since 1976, is equated to being “non-native”. Chan here solidifies the WHO’s gaze as non-African since Ebola would not be something exotic if Chan regarded the WHO as a truly international organization made by and for all countries. Instead, she posits Ebola and thus Liberia, as a West African nation, as the WHO’s Other.

Chan continues her problematic characterization of Ebola by pitting Ebola and Liberia in contrast to modernity, urbanism and sophistication. In her November 2015 speech, Chan placess Ebola in disparity to previous plagues, particularly to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), which she characterizes as a “modern plague”, leading the listener to assume that Ebola is somehow not a modern plague.[55] Since Chan has equated Ebola to Africa and Ebola as not modern, she equates Africa as not modern.

Chan also works to create a dichotomy between “sophisticated” and “urban”, namely the descriptors of the places where SARS took place, and the “poor” and “least prepared” places where Ebola took place, when stating:

The Ebola outbreak in West Africa evolved within a very different context. Whereas SARS was largely a disease of sophisticated urban settings, Ebola took its heaviest toll on three of the poorest and least prepared countries on earth.[56]

She ignores that the sophisticated and urban places also had a tremendous challenge before them when dealing with SARS because they too were poorly prepared. Moreover, Ebola was confronted in all three capital cities of West Africa, namely Monrovia, Conakry and Freetown, and that being poor and less prepared, even when true, would not equate West Africa to being an unsophisticated rural setting.

Furthermore, Chan imagines Liberians as “noble savages”, or as innocent and uncivilized humans unable to control emotion with reason. For example, Chan positions Ebola as a predator preying on innocent Liberians’ cultural practises, when stating:

But above all, the virus exploited West Africa’s deep-seated cultural traditions.[57]

This is also visible when Chan mobilizes the language of Ebola as a marauder attacking Liberians’ emotional economy.

Ebola preyed on another deep-seated cultural trait: compassion.[58]

Chan argues that when Ebola attacks compassion in care-taking practises, it attacks something specifically Liberian. By assuming that compassion is something particular to Liberia and West Africa, Chan initiates once again the process of Othering that she does throughout all her speeches to position the WHO’s gaze as divergent to Liberians.

This pattern was continued in Chan’s November 2015 address where she further characterized Liberia and its citizens as exacerbating the spread of Ebola through “centuries-old cultural beliefs and traditions” and indicated the Liberians were somehow stuck in the past.

IV. Discussion

This research was inspired by considerations of how public trust operates in a developing setting during a PHEIC, how the developing state positions itself during such an event, and how international actors operate vis-à-vis that state. A critical overview of the research pointed to a body of knowledge outlining the importance of public trust during a PHEIC, its empirical manifestation in Liberia during the Ebola crisis, and the manner in which international actors viewed the Liberian state and its citizens during the Ebola crisis. Work such as that of Blair, Morse, and Tsai (2016) establishes that citizens did not follow anti-transmission practises issued by the government, even when they believed in them, because of their indication that they did not trust the government enough. Moreover, research such as that of Monson (2017) argues that:

The US news media tapped into Americans’ fear and conceptualization of Ebola as “other”, “scary”, and “African”, which led to the othering of Africa, Africans, and those returning from Africa.[59]

However, the research body remains somewhat repetitive and scant given the under-studied nature of the region and the fact that events were relatively recent. The literature, moreover, does not create a wider conceptual image of the very particular developmental setting and events which occurred and does not question the changing roles of the citizens, the state and international actors as principals and agents.

This research taps into the available data to provide a snapshot of what relationships between the three actors looked like before, during, and after Ebola. The data and its analysis could have taken many other forms. For example, face-to-face interviews would provide a more robust and detailed dataset for analysis. An interview with David Nabarro, for instance, could provide more information on his views on Liberians, as the data here did not provide, surprisingly so, conclusive findings. However, I choose to analyse data not analysed before which lends itself elegantly to quantitative and discourse analysis, providing a convincing picture. Practical considerations also play a role; contacting actors during a pandemic and particularly those in Liberia is a hard task with the resources provided. Beyond the data, methods of approaching it could also be improved. Firstly, research with greater time, money and space limits would do well to analyse how the roles of principals and agents change during a PHEIC or how the roles of one actor, such as the citizenry, change. Secondly, another approach would be to conduct an in-depth comparative case study where the experience of Ebola in Liberia could be compared to the experience of COVID-19 in another developing or even developed nation. For example, a similar outlook could be applied to neighbouring Sierra Leone and Guinea to analyse potential similarities and/or differences. Finally, a potentially bountiful area of research would be to provide a gender analysis of Liberia and/or other countries’ experience of PHEICs. Most nurses caring for Liberian Ebola patients were women, and of the five (inter)national leaders whose speeches are here analysed, three are women. A gendered analysis would greatly serve the construction of a sophisticated snapshot.

Why is it important to paint a picture of the relations between these three different types of actors during Ebola anyways? I offer three main reasons, each relating to one type of actor and unmistakably positioning them within the context of a PHEIC. Firstly, it is imperative to discuss what role developing states have in preventing and answering to crises in public health. As threats to public health increasingly deny the existence of man-made borders in a globalized world, developing states are left without the capacity to prevent and control outbreaks which threaten whole regions and even the world. Yet, as the experience of Ebola shows, it was the nation-state which was first and foremost in responding to Ebola. Finally, the role of the international community in responding to PHEICs in developing contexts must be critically re-examined. Many questions here arise that need answering: whose interests do international actors represent, how do they position themselves vis-à-vis developing states’ leaders and citizens, and do their actions work in practise or falter? For example, the experience of Ebola in Liberia shows that a lack of cultural sensitivity on the part of international actors and their messages created a tendency to ignore anti-transmission practises. Secondly, considerations of the role local communities have during PHEICs, whether they be the BAME community in the UK or residents of Monrovia’s slums, are increasingly pertinent. The experience of Ebola in Liberia dictates that local community engagement is pivotal in reversing transmission trends and implementing a whole host of positive public health policies, such as the tailoring of programs to local conditions for increased effectiveness.

Finally, this research hopes to inspire policies implementing its insights into practise. Prospective policies include further enhancing the resilience and adaptability of developing states’ health systems and doing this especially on the local level where citizens and local leaders are best adept at responding with knowledge of local cultural norms during PHEICs. This would mean much more close contact to local leaders, or implementation of regional hubs, as detailed by Sherif and Maina (2013), but for the adaption of health and not security policy. Another potential policy area would spring from a critical questioning of the WHO’s functioning. This is a particularly salient policy region today as the US, one of the WHO’s largest donors, leaves that organisation. For the WHO to still be relevant, it will need to assess its own principal-agent relations with each country, especially those with struggling health systems.

V. Conclusion

This research posits that as the number of new Ebola cases rises, public trust declines while also showcasing the fact that the Liberian state sought to justify its actions whilst international actors saw themselves as saviours and Liberians and Ebola-ridden Liberia as backwards.

I would like to finish off by providing space for the scantily available voice of Liberian Ebola survivors while showcasing local actions. Following the insight that Ebola can exist in semen for up to 18 months, efforts such as the Men’s Health Screening Program offer sexual and mental health support to men who have had Ebola. Participants highlight the importance of locals administering programs which regard sensitive matters related to sex and Ebola. Through the programme, hope is born in Liberian survivors who have created the motto: I will be successful. I will be valuable. I will make an impact.[60]

Appendices

Appendix 1: R Code

## Liberians’ Trust in their President before, during, and after Ebola ##

names(Test_4)[names(Test_4) == “new cases”] <- “new_cases”

names(Test_4)[names(Test_4) == “trust in president”] <- “trust_in_president”

lmTest4 = lm(trust_in_president~new_cases, data = Test_4)

summary(lmTest4)

x <- Test_4$new_cases

y <- Test_4$trust_in_president

plot(x, y, main = “Liberians’ trust in their President as Ebola cases rise (2011-2018)”,

xlab = “New Ebola Cases in Liberia”, ylab = “Liberians’ trust in their President”)

model <- loess(y ~ x , Test_4)

new.Test_4 <- data.frame(x, y)

new.Test_4$fit <- predict(model, new.Test_4)

with(x, y, plot(x, y, ylim=c(0,5)))

with(new.Test_4, lines(x, fit))

## Liberians’ Trust in their Parliament before, during, and after Ebola ##

names(Cases_Parl_Trust_Excel)[names(Cases_Parl_Trust_Excel) == “new_cases”] <- “new_cases”

names(Cases_Parl_Trust_Excel)[names(Cases_Parl_Trust_Excel) == “trust_parl”] <- “trust_parl”

lm_Test_Parl = lm(trust_parl~new_cases, data = Cases_Parl_Trust_Excel)

summary(lm_Test_Parl)

x <- Cases_Parl_Trust_Excel$new_cases

y <- Cases_Parl_Trust_Excel$trust_parl

plot(x, y, main = “Liberians’ trust in their Parliament as Ebola cases rise (2011-2018)”,

xlab = “New Ebola Cases in Liberia”, ylab = “Liberians’ trust in their Parliament”)

model <- loess(y ~ x , Cases_Parl_Trust_Excel)

new.Cases_Parl_Trust_Excel <- data.frame(x, y)

new.Cases_Parl_Trust_Excel$fit <- predict(model, new.Cases_Parl_Trust_Excel)

with(x, y, plot(x, y, ylim=c(0,5)))

with(new.Cases_Parl_Trust_Excel, lines(x, fit))

Appendix 2: Time series survey data showcasing Liberians’ trust in their President as provided on Afrobarometer

Appendix 3: Time series survey data showcasing Liberians’ trust in their President as provided on Afrobarometer

Bibliography

Abramowitz, Sharon. “Epidemics (Especially Ebola).” Annual Review of Anthropology 46, no. 1 (October 23, 2017): 421–45. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102116-041616.

Abramowitz, Sharon, Sarah Lindley McKune, Mosoka Fallah, Josephine Monger, Kodjo Tehoungue, and Patricia A. Omidian. “The Opposite of Denial: Social Learning at the Onset of the Ebola Emergency in Liberia.” Journal of Health Communication 22, no. sup1 (March 2017): 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2016.1209599.

Ali, Harris, Barlu Dumbuya, Michaela Hynie, Pablo Idahosa, Roger Keil, and Patricia Perkins. “The Social and Political Dimensions of the Ebola Response: Global Inequality, Climate Change, and Infectious Disease.” In Climate Change and Health, edited by Walter Leal Filho, Ulisses M. Azeiteiro, and Fátima Alves, 151–69. Climate Change Management. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24660-4_10.

at Legal Information Institute. “Public Trust Doctrine.” LII / Legal Information Institute, NA. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/public_trust_doctrine.

Barker, Kathryn M, Emilia J Ling, Mosoka Fallah, Brian VanDeBogert, Yvonne Kodl, Rose Jallah Macauley, K Viswanath, and Margaret E Kruk. “Community Engagement for Health System Resilience: Evidence from Liberia’s Ebola Epidemic.” Health Policy and Planning 35, no. 4 (May 1, 2020): 416–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czz174.

Beekman, Gonne, Erwin Bulte, and Eleonora Nillesen. “Corruption, Investments and Contributions to Public Goods: Experimental Evidence from Rural Liberia.” Journal of Public Economics 115 (July 1, 2014): 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.04.004.

Bemah, Philip, April Baller, Catherine Cooper, Moses Massaquoi, Laura Skrip, Julius Monday Rude, Anthony Twyman, et al. “Strengthening Healthcare Workforce Capacity during and Post Ebola Outbreaks in Liberia: An Innovative and Effective Approach to Epidemic Preparedness and Response.” Pan African Medical Journal 33 (May 31, 2019). https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.supp.2019.33.2.17619.

Blair, Robert A., Benjamin S. Morse, and Lily L. Tsai. “Public Health and Public Trust: Survey Evidence from the Ebola Virus Disease Epidemic in Liberia.” Social Science & Medicine 172 (January 1, 2017): 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.016.

Briand, Sylvie, Eric Bertherat, Paul Cox, Pierre Formenty, Marie-Paule Kieny, Joel K. Myhre, Cathy Roth, Nahoko Shindo, and Christopher Dye. “The International Ebola Emergency.” New England Journal of Medicine 371, no. 13 (September 25, 2014): 1180–83. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1409858.

Chan. “WHO | From Crisis to Sustainable Development: Lessons from the Ebola Outbreak.” WHO. World Health Organization, March 10, 2015. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/2015/ebola-lessons-lecture/en/.

———. “WHO | WHO Director-General Addresses Princeton – Fung Global Forum on Lessons Learned from the Ebola Crisis.” WHO. World Health Organization, November 2, 2015. http://www.who.int/dg/speeches/2015/princeton-ebola-lessons/en/.

Dijk, Teun A. van. “Principles of Critical Discourse Analysis.” Discourse & Society 4, no. 2 (April 1, 1993): 249–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926593004002006.

Editors at Afrobarometer. “The Online Data Analysis Tool | Afrobarometer,” NA. https://www.afrobarometer.org/online-data-analysis/analyse-online.

Editors at the CDC. “Case Counts,” February 19, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/case-counts.html.

Elston, J.W.T., C. Cartwright, P. Ndumbi, and J. Wright. “The Health Impact of the 2014–15 Ebola Outbreak.” Public Health 143 (February 1, 2017): 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.10.020.

Fallah, Mosoka, Bernice Dahn, Tolbert G. Nyenswah, Moses Massaquoi, Laura A. Skrip, Dan Yamin, Martial Ndeffo Mbah, et al. “Interrupting Ebola Transmission in Liberia Through Community-Based Initiatives.” Annals of Internal Medicine 164, no. 5 (March 1, 2016): 367. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-1464.

Flyvbjerg, Bent. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12, no. 2 (April 1, 2006): 219–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363.

Foucault. The Order of Discourse, 1970. https://www.kit.ntnu.no/sites/www.kit.ntnu.no/files/Foucault_The%20Order%20of%20Discourse.pdf.

Furman, Katherine. “The International Response to the Ebola Outbreak Has Excluded Africans and Their Interests |.” Africa at LSE (blog), August 20, 2014. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2014/08/20/the-international-response-to-the-ebola-outbreak-has-excluded-africans-and-their-interests/.

Gambetta, Diego. Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations. Blackwell, 1988. https://philpapers.org/rec/GAMTMA.

Gerring, John. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices. Second edition. Strategies for Social Inquiry. Cambridge, United Kingdom New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2017. https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=CbetAQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=Case+study+research:+principles+and+practices+gerring&ots=kbG6NNMUzH&sig=_-e7Y7jJmPaAFW8lMqEDHGEXpaQ#v=onepage&q=Case%20study%20research%3A%20principles%20and%20practices%20gerring&f=false.

Gostin, Lawrence O. “Ebola: Towards an International Health Systems Fund.” The Lancet 384, no. 9951 (October 4, 2014): e49–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61345-3.

Gujadhur. “Postconflict Economic Governance Reform: The Experience of Ebola.” In Yes, Africa Can: Success Stories from a Dynamic Continent. World Bank Publications, 2011. https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/Yes_Africa_Can.html?id=4LlaYqIyAWAC&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=gujadhur&f=false.

Hawkins, Darren G., ed. Delegation and Agency in International Organizations. Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions. Cambridge, UK ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006. https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/Delegation_and_Agency_in_International_O.html?id=KTIbxACnMgYC&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Hofman, Michiel, and Sokhieng Au, eds. The Politics of Fear: Médecins sans Frontières and the West African Ebola Epidemic. New York, NY, United States of America: Oxford University Press, 2017. https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/4280019/mod_resource/content/1/Sokhieng%20Au%2C%20Michiel%20Hofman-The%20politics%20of%20fear%20_%20M%C3%A9decins%20sans%20fronti%C3%A8res%20and%20the%20West%20A.pdf.

Kamradt-Scott, Adam. “WHO’s to Blame? The World Health Organization and the 2014 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa.” Third World Quarterly 37, no. 3 (March 3, 2016): 401–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1112232.

Karim, Sabrina. “Restoring Confidence in Post-Conflict Security Sectors: Survey Evidence from Liberia on Female Ratio Balancing Reforms.” British Journal of Political Science 49, no. 3 (June 28, 2017): 799–821. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123417000035.

Kingsbury, Grace. “(PDF) To What Extent Was the Western Handling of the Ebola Crisis an Example of Neo- Imperialism?” ResearchGate. Accessed August 27, 2020. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.28397.54242.

Kobayashi, Beer, Bjork, Chatham-Stephens, Cherry, Arzoaquoi, Frank, et al. “Community Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Ebola Virus Disease — Five Counties, Liberia, September–October, 2014,” July 10, 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6426a2.htm.

Kruk, Margaret E, Emilia J Ling, Asaf Bitton, Melani Cammett, Karen Cavanaugh, Mickey Chopra, Fadi el-Jardali, et al. “Building Resilient Health Systems: A Proposal for a Resilience Index.” BMJ, May 23, 2017, j2323. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j2323.

Kucharski, A, and P Piot. “Containing Ebola Virus Infection in West Africa.” Eurosurveillance 19, no. 36 (September 11, 2014): 20899. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.36.20899.

“Liberian Ebola Survivor Program Provides Education, Counseling, and Hope | Division of Global Health Protection | Global Health | CDC,” July 12, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/stories/liberia-survivor-program.html.

Liu, Joanne. “Ebola UN Speech: ‘The Response Remains Totally, and Lethally, Inadequate,’” September 16, 2014. https://www.msf.org.uk/article/ebola-un-speech-response-remains-totally-and-lethally-inadequate.

Macdougall. “Liberian Government’s Blunders Pile Up in the Grip of Ebola.” Time, September 2, 2014. https://time.com/3247089/liberia-west-point-quarantine-monrovia/.

Mama, Amina. “Is It Ethical to Study Africa? Preliminary Thoughts on Scholarship and Freedom.” African Studies Review 50, no. 1 (April 1, 2007): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/20065338.

Mara, Gerald M. “Thucydides and Plato on Democracy and Trust.” The Journal of Politics 63, no. 3 (August 1, 2001): 820–45. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2691715.

Morse, Ben, Karen A Grépin, Robert A Blair, and Lily Tsai. “Patterns of Demand for Non-Ebola Health Services during and after the Ebola Outbreak: Panel Survey Evidence from Monrovia, Liberia.” BMJ Global Health 1, no. 1 (May 18, 2016): e000007. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2015-000007.

Nabarro. “WHO | Ebola Will Not Be Gone in Any Country until It Is Gone from Every Country.” WHO. World Health Organization, January 26, 2015. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/events/2015/eb136/speech-david-nabarro/en/.

Nuriddin, Azizeh, Mohamed F Jalloh, Erika Meyer, Rebecca Bunnell, Franklin A Bio, Mohammad B Jalloh, Paul Sengeh, et al. “Trust, Fear, Stigma and Disruptions: Community Perceptions and Experiences during Periods of Low but Ongoing Transmission of Ebola Virus Disease in Sierra Leone, 2015.” BMJ Global Health 3, no. 2 (April 1, 2018): e000410. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000410.

Nyenswah, Tolbert, Cyrus Y. Engineer, and David H. Peters. “Leadership in Times of Crisis: The Example of Ebola Virus Disease in Liberia.” Health Systems & Reform 2, no. 3 (July 2, 2016): 194–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2016.1222793.

Nyenswah, Tolbert G., Francis Kateh, Luke Bawo, Moses Massaquoi, Miatta Gbanyan, Mosoka Fallah, Thomas K. Nagbe, et al. “Ebola and Its Control in Liberia, 2014–2015.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 22, no. 2 (February 1, 2016): 169–77. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2202.151456.

Obama, Barack. “Remarks by President Obama at U.N. Meeting on Ebola.” whitehouse.gov, September 25, 2014. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/09/25/remarks-president-obama-un-meeting-ebola.

Onder. “(PDF) What Accounts for Changing Public Trust in Government? A Causal Analysis with Structural Equation Model.” ResearchGate, January 1, 2011. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312947926_What_Accounts_for_Changing_Public_Trust_in_Government_A_Causal_Analysis_with_Structural_Equation_Model.

Pellecchia, Umberto, Rosa Crestani, Tom Decroo, Rafael Van den Bergh, and Yasmine Al-Kourdi. “Social Consequences of Ebola Containment Measures in Liberia.” Edited by Lidia Adriana Braunstein. PLOS ONE 10, no. 12 (December 9, 2015): e0143036. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143036.

Piot, Peter, Jean-Jacques Muyembe, and W John Edmunds. “Ebola in West Africa: From Disease Outbreak to Humanitarian Crisis.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases 14, no. 11 (November 4, 2014): 1034–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70956-9.

Podder, Sukanya. “Bridging the ‘Conceptual–Contextual’ Divide: Security Sector Reform in Liberia and UNMIL Transition.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 7, no. 3 (September 1, 2013): 353–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2013.770242.

“PUBLIC TRUST | Meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary,” NA. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/public-trust.

“Report for Selected Countries and Subjects,” July 1, 2020. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=43&pr.y=8&sy=2013&ey=2020&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=668%2C724%2C656&s=NGDPD&grp=0&a=.

Richardson Oakes, Anne. “Judicial Resources and the Public Trust Doctrine: A Powerful Tool of Environmental Protection?” Transnational Environmental Law 7, no. 3 (September 17, 2018): 469–89. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2047102518000213.

Roemer-Mahler, Anne, and Simon Rushton. “Introduction: Ebola and International Relations.” Third World Quarterly 37, no. 3 (March 3, 2016): 373–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1118343.

Sabuni, Louis Paluku. “Dilemma With the Local Perception of Causes of Illnesses in Central Africa: Muted Concept but Prevalent in Everyday Life.” Qualitative Health Research 17, no. 9 (November 1, 2007): 1280–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307307864.

Sarah Monson. “Ebola as African: American Media Discourses of Panic and Otherization.” Africa Today 63, no. 3 (April 1, 2017): 3. https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.63.3.02.

Scott, Vera, Sarah Crawford-Browne, and David Sanders. “Critiquing the Response to the Ebola Epidemic through a Primary Health Care Approach.” BMC Public Health 16, no. 1 (May 17, 2016): 410. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3071-4.

Sherif, and Maina. “Enhancing Security and Justice in Liberia.” ACCORD (blog), March 1, 2013. https://www.accord.org.za/publication/enhancing-security-and-justice-in-liberia/.

Shorten, Allison, and Joanna Smith. “Mixed Methods Research: Expanding the Evidence Base.” Evidence Based Nursing 20, no. 3 (July 26, 2017): 74–75. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2017-102699.

Siddique, Haroon, and Sarah Marsh. “Inquiry Announced into Disproportionate Impact of Coronavirus on BAME Communities.” The Guardian, April 16, 2020, sec. World news. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/16/inquiry-disproportionate-impact-coronavirus-bame.

Siisiainen, and Martti. “(PDF) Two Concepts of Social Capital: Bourdieu vs. Putnam.” ResearchGate, January 1, 2000. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/200031251_Two_Concepts_of_Social_Capital_Bourdieu_vs_Putnam.

Sirleaf. “A Special Statement by the President,” July 28, 2014. https://www.emansion.gov.lr/doc/Special%20Statement%20by%20President%20Ellen%20Johnson%20Sirleaf%20-1_1.pdf.

———. “Nationwide Statement by Madam Ellen Johnson Sirleaf President of the Republic of Liberia on the Ebola Virus,” June 8, 2014. https://www.emansion.gov.lr/doc/Nationwide%20Statement%20on%20the%20Ebola%20virus%20by%20the%20President%20of%20the%20%20Republic%20of%20Liberia,%20Madam%20Ellen%20Johnson%20Sirleaf(1).pdf.

———. “Nationwide Statement by Madam Ellen Johnson Sirleaf President of the Republic of Liberia on the Ebola Virus,” September 9, 2014. https://www.emansion.gov.lr/doc/WorldBank_Statement.pdf.

———. “Special Statement by Ellen Johson Sirleaf On Additional Measures in the Fight against the Ebola Viral Disease,” July 30, 2014. https://www.emansion.gov.lr/doc/Special_State_Delivered_July%2030.pdf.

———. “Statement by Her Excellency President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf on the Update of the Ebola Crisis,” September 17, 2014. https://www.emansion.gov.lr/doc/Nation_Address-17092014.pdf.

Southall, Hannah Grace, Sarah E. DeYoung, and Curt Andrew Harris. “Lack of Cultural Competency in International Aid Responses: The Ebola Outbreak in Liberia.” Frontiers in Public Health 5 (January 31, 2017). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00005.

ReliefWeb. “Surviving Ebola: Public Perceptions of Governance and the Outbreak Response in Liberia – Liberia,” June 30, 2015. https://reliefweb.int/report/liberia/surviving-ebola-public-perceptions-governance-and-outbreak-response-liberia.

Tejpar, Ali, and Steven J. Hoffman. “Canada’s Violation of International Law during the 2014–16 Ebola Outbreak.” Canadian Yearbook of International Law/Annuaire Canadien de Droit International 54 (October 2, 2017): 366–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/cyl.2017.18.

WHO | Regional Office for Africa. “The Ebola Outbreak in Liberia Is Over,” May 9, 2015. https://www.afro.who.int/news/ebola-outbreak-liberia-over.

Thompsell. “Key Moments in the History of Liberia.” ThoughtCo, July 24, 2020. https://www.thoughtco.com/brief-history-of-liberia-4019127.

Toppenberg-Pejcic, Deborah, Jane Noyes, Tomas Allen, Nyka Alexander, Marsha Vanderford, and Gaya Gamhewage. “Emergency Risk Communication: Lessons Learned from a Rapid Review of Recent Gray Literature on Ebola, Zika, and Yellow Fever.” Health Communication 34, no. 4 (March 21, 2019): 437–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2017.1405488.

Trčková, Dita. “Representations of Ebola and Its Victims in Liberal American Newspapers.” Topics in Linguistics 16, no. 1 (December 1, 2015): 29–41. https://doi.org/10.2478/topling-2015-0009.

Tsai, Lily L., Benjamin S. Morse, and Robert A. Blair. “Building Credibility and Cooperation in Low-Trust Settings: Persuasion and Source Accountability in Liberia During the 2014–2015 Ebola Crisis.” Comparative Political Studies 53, no. 10–11 (September 1, 2020): 1582–1618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019897698.

Van de Walle, Steven, and Geert Bouckaert. “Public Service Performance and Trust in Government: The Problem of Causality.” International Journal of Public Administration 26, no. 8–9 (February 7, 2007): 891–913. https://doi.org/10.1081/PAD-120019352.

Vinck, Patrick, Phuong N Pham, Kenedy K Bindu, Juliet Bedford, and Eric J Nilles. “Institutional Trust and Misinformation in the Response to the 2018–19 Ebola Outbreak in North Kivu, DR Congo: A Population-Based Survey.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases 19, no. 5 (March 27, 2019): 529–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30063-5.

Human Rights Watch. “West Africa: Respect Rights in Ebola Response,” September 15, 2014. https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/09/15/west-africa-respect-rights-ebola-response.

Woldemariam, Yohannes, and Lionel Di Giacomo. “Ebola Epidemic.” Air & Space Power Journal – Africa and Francophonie 7, no. 1 (March 22, 2016): 54–73. https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=AONE&sw=w&issn=1931728X&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA455186429&sid=googleScholar&linkaccess=abs.

Woskie, Liana R, and Mosoka P Fallah. “Overcoming Distrust to Deliver Universal Health Coverage: Lessons from Ebola.” BMJ, September 23, 2019, l5482. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l5482.

Notes

[1] Siddique, Haroon, and Sarah Marsh. “Inquiry Announced into Disproportionate Impact of Coronavirus on BAME Communities.” The Guardian, April 16, 2020, sec. World news. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/16/inquiry-disproportionate-impact-coronavirus-bame.

[2] I take the Western world to generally be comprised of North American and European (mostly Western European) developed nations.

[3] Ali, Harris, Barlu Dumbuya, Michaela Hynie, Pablo Idahosa, Roger Keil, and Patricia Perkins. “The Social and Political Dimensions of the Ebola Response: Global Inequality, Climate Change, and Infectious Disease.” In Climate Change and Health, edited by Walter Leal Filho, Ulisses M. Azeiteiro, and Fátima Alves, 151–69. Page 161. Climate Change Management. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24660-4_10.

[4] Throughout this Dissertation, the 2011 to 2018 period is used since the survey data is from that period. However, the Ebola crisis in Liberia ran from 2014 to 2016.

[5] Hawkins, Darren G., ed. Delegation and Agency in International Organizations. Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions. Cambridge, UK ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006. Page 7. https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/Delegation_and_Agency_in_International_O.html?id=KTIbxACnMgYC&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[6] Editors at Legal Information Institute. “Public Trust Doctrine.” LII / Legal Information Institute, NA. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/public_trust_doctrine.

[7]“PUBLIC TRUST | Meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary,” NA. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/public-trust.

[8] Van de Walle, Steven, and Geert Bouckaert. “Public Service Performance and Trust in Government: The Problem of Causality.” International Journal of Public Administration 26, no. 8–9 (February 7, 2007): 891–913 (Page 909). https://doi.org/10.1081/PAD-120019352.

[9] Siisiainen, and Martti. “(PDF) Two Concepts of Social Capital: Bourdieu vs. Putnam.” ResearchGate, January 1, 2000. Page 1. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/200031251_Two_Concepts_of_Social_Capital_Bourdieu_vs_Putnam.

[10]Gambetta, Diego. Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations. Blackwell, 1988. https://philpapers.org/rec/GAMTMA.

[11] Sherif, and Maina. “Enhancing Security and Justice in Liberia.” ACCORD (blog), March 1, 2013. Page 8. https://www.accord.org.za/publication/enhancing-security-and-justice-in-liberia/.

[12] Podder, Sukanya. “Bridging the ‘Conceptual–Contextual’ Divide: Security Sector Reform in Liberia and UNMIL Transition.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 7, no. 3 (September 1, 2013): 353–80 (Page 374). https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2013.770242.

[13] Karim, Sabrina. “Restoring Confidence in Post-Conflict Security Sectors: Survey Evidence from Liberia on Female Ratio Balancing Reforms.” British Journal of Political Science 49, no. 3 (June 28, 2017): 799–821 (Page 799). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123417000035.

[14] Beekman, Gonne, Erwin Bulte, and Eleonora Nillesen. “Corruption, Investments and Contributions to Public Goods: Experimental Evidence from Rural Liberia.” Journal of Public Economics 115 (July 1, 2014): 37–47 (Page 44). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.04.004.

[15] Barker, Kathryn M, Emilia J Ling, Mosoka Fallah, Brian VanDeBogert, Yvonne Kodl, Rose Jallah Macauley, K Viswanath, and Margaret E Kruk. “Community Engagement for Health System Resilience: Evidence from Liberia’s Ebola Epidemic.” Health Policy and Planning 35, no. 4 (May 1, 2020): 416–23 (Page 416). https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czz174.

[16] Tsai, Lily L., Benjamin S. Morse, and Robert A. Blair. “Building Credibility and Cooperation in Low-Trust Settings: Persuasion and Source Accountability in Liberia During the 2014–2015 Ebola Crisis.” Comparative Political Studies 53, no. 10–11 (September 1, 2020): 1582–1618 (Page 1582). https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019897698.