Why has China alarmed its neighbours and risked military conflict in pursuit of its vast disputed claims in the South China Sea? I argue the answer lies in long-term patterns of continuity and change in China’s policy. Conventional wisdom says it’s just about China’s expanding power. Yet both the expansion of the PRC’s sweeping claims there, and many of its boldest moves – including the use of military force against Vietnam in 1974 and 1988 – happened decades back, when China was much weaker than today. There’s no shortage of alternative arguments: insecurity, resources, rising domestic nationalism, zealous frontline agencies, elite political struggles, the ascendance of Xi Jinping, and so on. The problem is that there is no agreement on what exactly has changed in the PRC’s policy, let alone when.

Next, I applied this framework to a unique time series dataset of 130 cases of change in PRC behaviour in the South China Sea each year from 1970 to 2015. It’s unique because it addresses a major skew in outside analysts’ information supply about the South China Sea — namely, the fact that there’s so much more information about events in recent years than in the past. To mitigate this “present-centric bias,” I looked through an array of Chinese sources on the PRC’s historical activities in the South China Sea dating back to 1970. This helped put Beijing’s current policies in context, while also clarifying the timing of events, as well as some key features that distinguish present PRC policy from past.

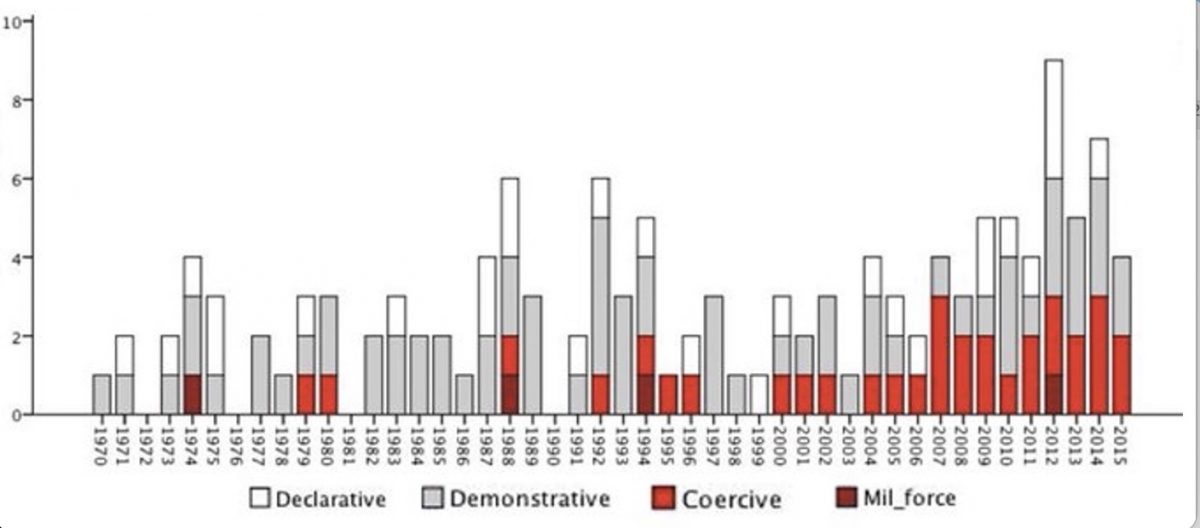

The findings? First of all, as mentioned above, China’s assertiveness has been increasing near-constantly from 1970 onwards. The most recent year in which China’s assertive behaviour did not intensify in some form was in 1990, in the wake of the Tiananmen crackdown. But amidst the steady advance, we also find surges in assertive activity starting from 1973, 1987 and 1992. Most importantly for present purposes, we see a real “program shift” from 2007 onwards.

Consider the cluster of red bars on the right-hand side of Figure 1. That’s the introduction of regular coercive acts such as harassment of Vietnamese and Philippine seismic survey activities, forcing Indonesia to release Chinese fisherfolk detained for fishing in its EEZ, threatening foreign oil companies cooperating with Vietnamese energy development in the disputed area, and in one case, confronting a US spy ship.

The new coercive behaviours have been accompanied by a rapid administrative buildup comprising increasing numbers of patrols, and then, from late 2013, construction of massive artificial islands on six reefs in the Spratly Archipelago. Those two basic distinguishing features of China’s policy – regular coercive acts and a rapid buildup of administrative presence – have persisted to the present. But they began in 2007, before the Global Financial Crisis called US’s long-term power into question, and long before Xi Jinping takes power. These two commonly-cited drivers of China’s maritime policy at most entrenched or exacerbated a policy that was already in motion.

It’s also well before the Chinese Internet start to lighted up with nationalist sentiments about the issue. Based on search activity data from Baidu, China’s dominant search engine, the online public’s demand for information on the South China Sea was flat until mid-2009.

What explains these patterns? The last part of the International Security article provides focused case studies of the four turning points apparent in the data: 1973, 1987, 1992 and 2007, drawing on an array of newly available Chinese sources (some of which helped fill in the dataset). I found the first three PRC surges in the South China Sea to be largely opportunistic responses to favourable geopolitical circumstances. But in contrast, the major policy change observed from 2007 traces back to decisions in the late 1990s to build long-range maritime law enforcement fleets. It was the maturation of these specific capabilities, rather than China’s military and economic hard power per se, that produced the change in 2007.

At each of the four turning points I found the PRC’s engagement with emerging Law of the Sea regime resulted in intensified pursuit of control over vast maritime spaces. Until 1973, the PRC’s stated interest in the South China Sea had been limited to small disputed islands. It was only after it joined negotiations for a UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) – a unique international treaty governing state jurisdiction over maritime spaces – that year that the PRC began asserting wide-ranging administrative rights over the waters in the area.

After the ratification of the UNCLOS in 1982, the PRC launched major efforts to survey the energy resources, hydrological conditions and marine life across the nine-dash line area. In 1987 it finally established a foothold in the Spratly Islands – the furthest flung archipelago in the South China Sea. In 1992, as the treaty neared the 60 ratifications required to come into force, the PRC’s assertiveness surged once again. It was the enshrining of the UNCLOS provisions into the PRC’s legal-administrative system in 1998 that prompted it to create a new maritime law enforcement agency – China Marine Surveillance – tasked with realizing China’s claims to sovereign jurisdiction around its maritime periphery.

It took several years for the new agency to acquire the equipment, know-how and confidence to effectively assert maritime jurisdiction in remote, tropical waters thousands of miles from the Chinese mainland, and in many cases close to the coasts of rival claimant states in Southeast Asia. By 2007 it was ready, and on the orders of the State Council, rolled out regular patrols across the nine-dash line area.

So, there’s a theoretical story here about the internalization – and reappropriation, as seen in the PRC’s recent attempts to defy the UNCLOS – of international normative frameworks. It seems that in at least some circumstances more law could prompt conflictual behaviour via the expansion and hardening of sovereign claims, rather than cooperation via lowered transaction costs and socialization, as institutional theories of international relations expect.

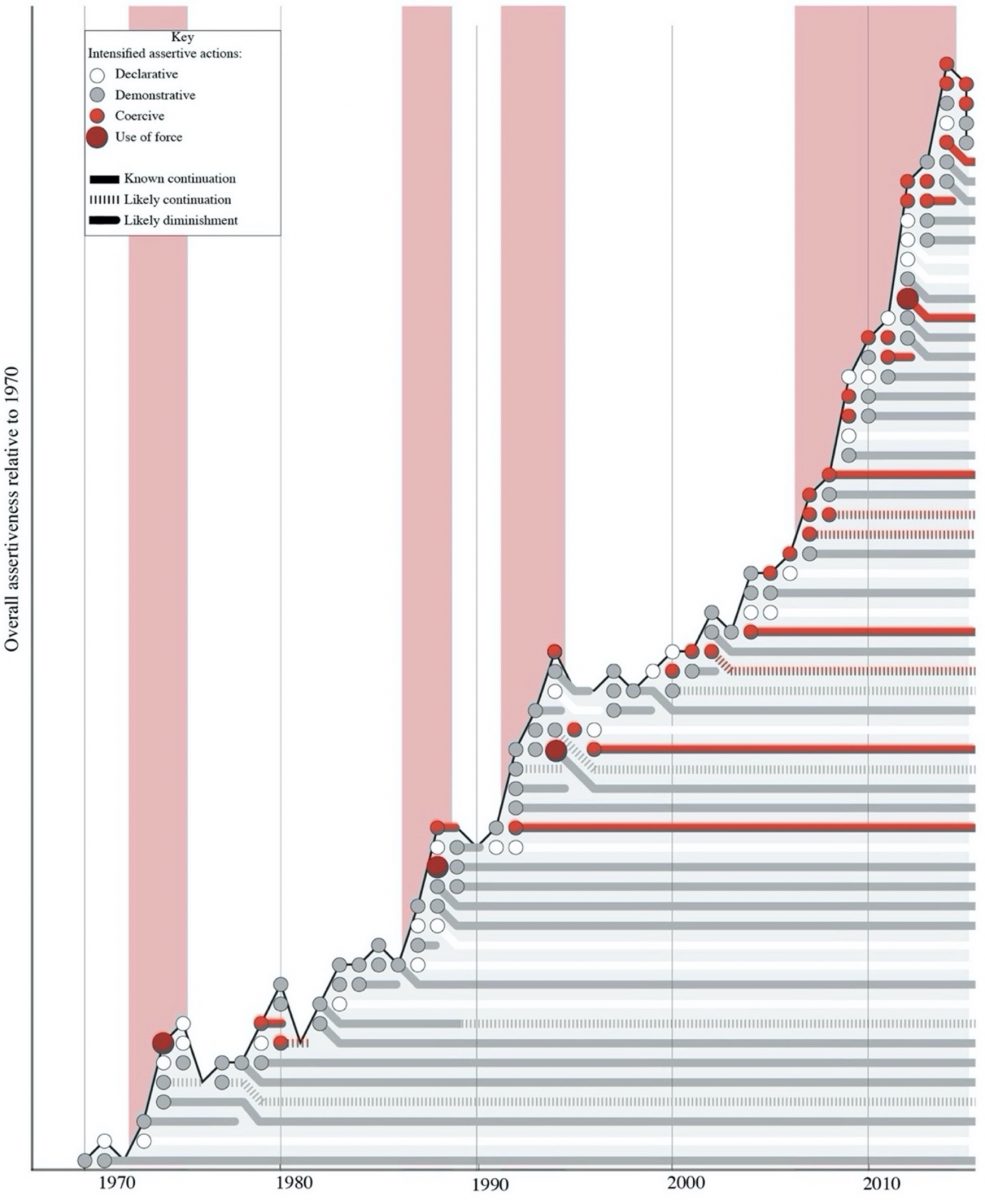

For analysts of foreign policy and international relations, a key takeaway is that the changes we observe in states’ dispute behaviour at one time are often lagged effects of decisions taken much earlier. The accumulating layers of assertive conduct in Figure 2 illustrates a crucial but little-noted dynamic of maritime and territorial disputes: the tendency of assertiveness to beget more assertiveness. Not only do new capabilities take time to bear fruit, but lines of action introduced at one point in time often open up possibilities for other activities in the future. A new patrol route, for example, tends to blaze a trail for further increases in patrolling as frontline actors gain experience and confidence operating in once unfamiliar areas.

The Philippines-China standoff over Scarborough Shoal in 2012 provides a vivid illustration of this dynamic. The PRC’s rapid on-water intervention to block the Philippines navy from arresting Chinese fishermen was only possible because two maritime surveillance vessels were fortuitously located nearby on a regular patrol. Such patrols only commenced in the South China Sea in 2007; five years later, they directly enabled the PRC’s seizure of a strategically located reef.

The pattern of accumulating layers in Figure 2 thus illustrate how assertiveness results not only from contemporary policy decisions, but also from groundwork laid down in previous years. For analysts, this means it may be necessary to consider not just the immediate triggers for an observed change in state behaviour in such geographically-constituted disputes, but also temporally distant decisions and slower-moving processes whose effects may only become observable years after being set in motion.

Policy-wise, the article suggests that skepticism is warranted regarding PRC claims that its assertiveness is a response to external provocations, such as when Beijing deployed anti-ship cruise missiles to the Spratly Islands in 2018, citing activity by the US Navy. But it also suggests officials should be cautious about attributing assertive acts to other-directed motives like undermining their deterrence credibility or weakening alliances. What appears, or feels, like a targeted move may be just another step toward a stated long-term goal.

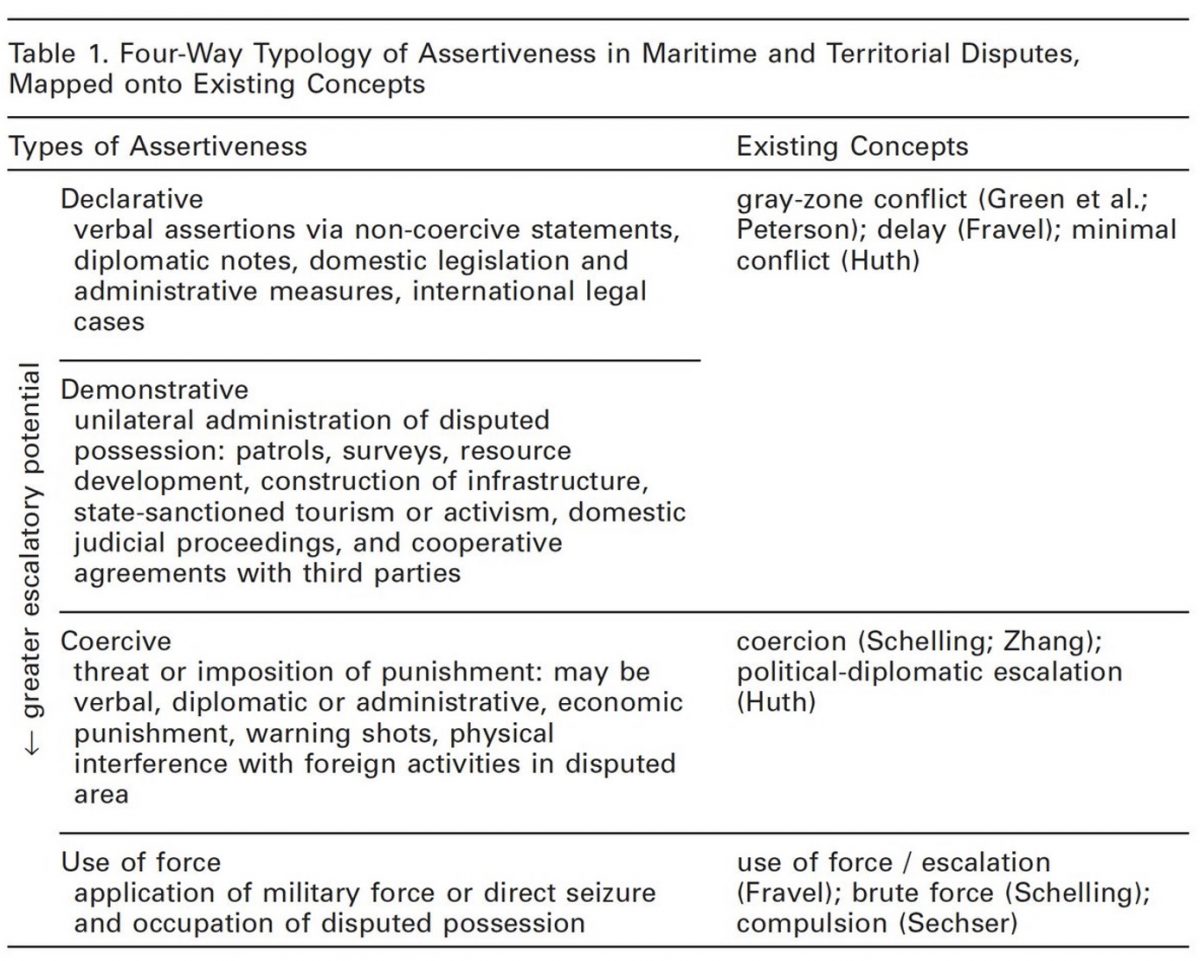

Some date the South China Sea push back to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008–2009; others point to Xi Jinping’s ascent to the Chinese Communist Party’s top leadership post in 2012, or various other dates in between. Without clarity about exactly what has changed and when, it’s hard to assess the why, because it turns out the PRC’s behaviour has been changing there almost every year since the 1970s. In ‘PRC Assertiveness in the South China Sea: Measuring Continuity and Change, 1970–2015’ (2021 International Security) I do this by distinguishing between four kinds of assertive acts, meaning those that unilaterally advance the state’s position in the dispute: declarative, demonstrative, coercive and use of force, illustrated in Table 1.

Figure 1. Intensifications of Assertiveness by the People’s Republic of China in the South China Sea by Type, 1970–2015.

Figure 2. Accumulation of assertive behaviours by the PRC in the South China Sea.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Is China Under-Exploiting One Legal Avenue in the South China Sea?

- Contesting American Power: Beijing’s Challenge in South China Sea Disputes

- The Role of ASEAN in the South China Sea Disputes

- The Implications of China’s Growing Military Strength on the Global Maritime Security Order

- The Taiwan Factor in the Clarification of China’s U-shaped Line

- The Role of United Nations Convention on the Laws of the Sea in the South China Sea Disputes