The signing of a defence agreement between the Maldives and the United States (US) in September 2020 was welcomed by India as a positive step towards regional cooperation (Rej, 2020). Historically cautious of extra-regional powers engaging in military and strategic activities in its Indian Ocean ‘backyard’, India has claimed a dominant role in terms of managing regional maritime boundaries. Located ‘barely 70 nautical miles away from Minicoy and 300 nautical miles away from India’s West coast, [and within] the hub of commercial sea‐lanes running through Indian Ocean (particularly the 8° N and 1 ½° N channels),’(Ministry of External Affairs, 2019a, p. 1) the Maldives occupies a critical strategic position in South Asia. A history of friendly ties and geographic proximity have ensured political trust, economic cooperation and coherent strategic polices between the two. Despite the historical bonds between these neighbours, their relationship took a sharp turn towards political uncertainty between 2013 and 2018 as a result of former Maldivian President Abdulla Yameen Abdul Gayoom’s pro-China policy (Rasheed, 2018, 2019, 2020). Bringing an extra-regional power like China into the South Asian periphery created significant political anxiety in India—a level of concern that was not apparent when the Maldives extended security-based cooperation with the US. This prejudice is linked to India’s role in the Indo-Pacific alliance with the US, Australia, and Japan to curb China’s potential strategic rise in the Asia-Pacific. All four Indo-Pacific states view China as a potential security threat in their regional peripheries where in that India has a greater role to curb the rise of extra-territorial powers in South Asia’s maritime boundaries (Baruah, 2020; Laskar, 2020; Ministry of External Affairs, 2018; Rehman, 2009). The Maldives-US defence cooperation is only one part of the broader role India plays in limiting China’s engagement in the region.

This article discusses how India’s central role in South Asia’s contemporary maritime security domain has been affected by the Maldives’ regional development policy. Contrary to orthodox international relations thinking that dominant and larger states often determine regional security dynamics, it argues that India has not always controlled or been certain about the Maldives’ regional foreign policy (Flockhart, 2008; Rasheed, 2018, 2019, 2020) and that the drivers of political certainty and strategic coherence in that domain are, in fact, often affected by the political choices of the Maldives. Former Maldivian president and political strongman Abdulla Yameen Abdul Gayoom started this trend in 2013 by adopting pro-China policies and drawing Chinese interests into the regional periphery (Rasheed, 2018, 2020). It became necessary for India to engage with the Maldives to curb China’s increasing influence over maritime boundaries of South Asia. However, India was able to influence Maldives-China policy only after pro-Western President Mohammed Solih came to power in November 2018. Solih’s new government reiterated the ‘India First’ policy and withdrew China as a priority development partner (Rasheed, 2020) which led to enhanced defence and strategic cooperation between India and the Maldives.

This viewpoint aligns with constructivism in international relations where shared ideas have a capacity to shape and re-shape inter-state relationships despite pre-existing norms and practices (Flockhart, 2016; Wendt, 1992). As constructivists would argue, despite the traditional Maldives-India regional partnerships, India’s ability to strengthen its closer ties with the Maldives has been shaped by the political choices and ideas of President Solih’s government to enhance defence and security cooperation with India as part of its regional foreign policy agenda (Rasheed, 2018, 2020). In line with this observation, this article aims to understand the potential opportunities and challenges for India in maintaining its leadership in the Indo-Pacific security space with respect to the Maldives. It explores government policy statements and decisions to demonstrate how political ideas can shape the Maldives’ foreign policy to drive a sustainable Maldives-India defence and security cooperation that supports India’s regional security objectives.

Political Ideas as Drivers of Regional Cooperation

During the period from 2013 to 2018, India experienced a period of political uncertainty in terms of the Maldives’ role in shaping regional power dynamics by adopting a pro-China policy for development cooperation. Former President Yameen’s policy to bring China closer to the Maldives was clearly defined by his approach to political and national development cooperation (Rasheed, 2020). In his 2017 Independence Day remarks, President Yameen asserted that the Maldives had moved its national efforts beyond domestic boundaries towards creating opportunities to compete with professionals and experts of international stature (President’s Office, 2017a; Rasheed, 2018).

Today, the national debate should be about whether we as a nation, have what it takes to strive and win the international race. [And that] … in the past four years, we have undertaken developmental work, unparalleled to any other developmental era, Yameen announced (President’s Office, 2017a).

As a small island developing state (SIDS) reliant on international and bilateral cooperation for development support, the Maldives was drawn to what China offered under its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Also known as One Belt, One Road (OBOR) the initiative aims to strengthen Beijing’s economic leadership in maritime states such as the Maldives through financial aid (Das, 2017; Rasheed, 2018, 2020).

The BRI is unique in that its host governments have political independence in determining how to receive and manage the funds and investments (Xinhuanet, 2017; State Council of PRC, 2014; Zhang & Huang; Zhang, Gu, and Chen, 2015). In contrast to Western-based aid agencies, China’s principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of its host countries made its aid conditions more attractive to Yameen’s government. Yameen’s political and economic ideas did not align with democratic governance and traditional development cooperation practices. His ideas did not meet the post-colonial development cooperation that imposed conditions on domestic affairs of the state. This is reflected by Yameen’s statement that

constitutional frameworks are designed in this manner to ensure that the interests of the state [the Maldivian government] reign supreme. [And that] …the battle, to keep influential colonial powers at bay, now emerges with fuel from within the Maldives (President’s Office, 2017a).

And it would make sense for a government that engaged in strongman practices to favour aid that supported its political and economic agenda without any impositions on its political office in terms of extra-territorial policies. Referring to the function of organisations like the United Nations, Yameen stressed that:

There will be no stability if one country can interfere in another’s internal affairs and there are not many things the UN can do when such interferences occur. … I would like to highlight that we can only move forward, and be respected if we are a self-sufficient, strong economy which can stand on its own feet. … [And that] we are trying to find easier ways for us to have access to aid by bringing in big investments. (Maldives Independent 2015)

The BRI’s aid model aligned with the political ideas that had shaped Yameen’s independent policy on development cooperation to support political stability (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China 2014; President’s Office 2014a; Joshi, 2018).

Considering President Yameen’s favouritism towards China, India raised concerns over negative implications of the Maldives-China engagement that could lead to increasing economic debt traps and strategic build-up that could potentially threaten the security of the South Asia region. An alleged operation of China’s naval fleet in South Asia’s territorial waters in aid of Yameen’s government in 2018 highlighted the geostrategic competition posed by China’s engagement in the Maldives’ territory (Rasheed, 2018). India could view China’s naval presence near the Maldives as an attempt to curb any efforts to intervene in the Yameen government’s activities during that time. The following statement was issued by a spokesperson from the Chinese Foreign Ministry in an attempt to justify the behaviour:

What is happening inside the Maldives is the internal affairs of the country. [And] the international community shall play a constructive role on the basis of respecting the sovereignty of the Maldives, instead of further complicating the situation. (Tiezzi, 2018).

India demanded greater transparency from the Maldives on regional security fronts. Reportedly, this was not well-received by the Yameen’s government, which countered with a forceful reply:

[Development cooperation in the Maldives] is an open invitation. …We have taken a lot of our projects to India as well, but we did not receive the necessary finance. (…) Our government has made it very clear that we are not going to allow any kind of military establishments or military undertakings in the Maldives. Not for China, not for any other countries.’ (South China Morning Post 2018)

Development cooperation between the Maldives and China was understood as mutually beneficial and not as a regional strategy.

Despite these engagements with China, the Maldives-China relationship was weakened following President Solih’s election, heralding a renewed policy shift towards enhanced Maldives-India cooperation (Rasheed, 2019). His new government sought help from India and the US immediately after the election ‘to climb out from under a mountain of Chinese debt.’ (Miglani & Mohamed, 2018). The ‘India First’ policy was moulded by political ideas about strengthening historically and geographically driven neighbourly relations between the two countries to promote bilateral and regional cooperation. Following several state and bilateral visits, political leaders of both the Maldives and India have celebrated renewed measures of development cooperation. To reiterate Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s words:

I will convey to the new Maldivian Government of Mr Solih the desire of the Indian Government to work closely for realisation of their developmental priorities, especially in areas of infrastructure, health care, connectivity and human resource development. (The Economic Times, 2020)

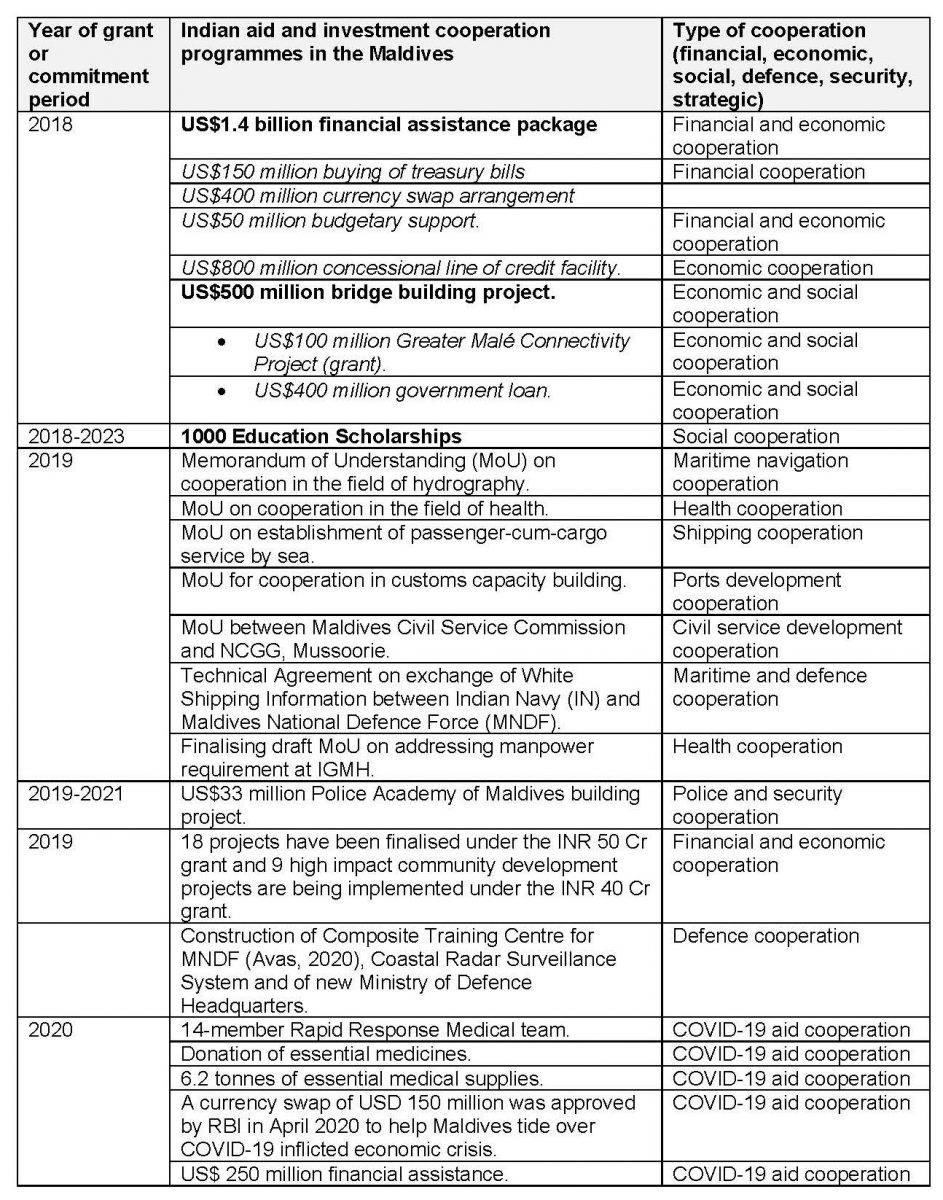

President Solih was quick to take his predecessor’s China policy under review and change his foreign policy to enhance partnerships with India as his political ideas aligned with the latter’s leadership role in South Asia. A joint statement by the two states during Prime Minister Modi’s state visit to the Maldives in 2019 announced that the ‘two leaders reiterated their strong commitment to further strengthening and invigorating the traditionally strong and friendly relations between India and the Maldives’ (Ministry of External Affairs, 2019b). The statement welcomed India’s aid and budgetary support of the Maldives to address potential debt crises arising from China’s investments undertaken during Yameen’s government. Under subsequent bilateral agreements, several development projects were implemented with the support of India’s US$800 million line of credit facility aid, including 1000 education scholarships over 5 years from 2018, US$100 million Greater Malé Connectivity Project (Miadhu, 2020), supply of building materials to develop public parks in 67 local islands and build bridges connecting the capital city Malé and regional and industrial islands. Table 1 summarises the key Indian aid and development cooperation programmes in the Maldives as of 2019. Table 1: The key Indian aid and development cooperation programmes in the Maldives (Ministry of External Affairs, 2019a).

India’s Strategic Step-up in the Maldives

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government embraced the Solih government’s ‘India First’ policy as an opportunity to enhance regional security cooperation. During an official visit of External Affairs Minister of India (EAM) Smt. Sushma Swaraj to the Maldives, the Foreign Minister of the Maldives ‘reiterated his Government’s “India-First Policy” and said that his Government looks forward to working closely with the Government of India on all issues’ (Ministry of External Affairs, 2019c). Noting renewed commitment to neighbourly relations between the two states, the Maldives Foreign Minister also reiterated that the Government of Maldives would remain sensitive to India’s security and strategic concerns. In 2019, a technical agreement was signed by the two states on sharing White Shipping information between the Indian Navy and the Maldives National Defence Force (MNDF). This agreement was part of a long-term commitment made by Prime Minister Modi during his state visit to the Maldives in June 2019 (Ministry of External Affairs, 2019b). Training activities (including Ekatha, conducted in April 2019) have been implemented to build capacity in the MNDF. According to India’s Ministry of External Affairs (2019a):

India has trained over 1250 MNDF trainees over the past 10 years and have offered 175 training vacancies in 2019‐20. MNDF has also been participating in various mil‐to‐mil activities such as sea‐rider programme, adventure camps, sailing regatta etc. [India has] … also offered to depute Mobile Training Teams (MTT) based on MNDF requirements and to train MNDF personnel for UN peace‐keeping operations at CUNPK. Indian Navy has deployed 10‐member Marine Commando MTT to Maldives in 2017, 2018 and 2019 and also provided MNDF with helo‐borne vertical insertion capability.

India has enhanced its strategic engagement in the territories of the Maldives. A June 2019 joint statement stated:

In recognition that the security interests of both countries are interlinked in the region, they reiterated their assurance of being mindful of each other’s concerns and aspirations for the stability of the region and not allowing their respective territories to be used for any activity inimical to the other. (Ministry of External Affairs, 2019b).

The strategic engagements have involved providing technical support, lending and granting naval or maritime vessels and installing coastal surveillance systems in Maldivian territories. In 2019, India reportedly gifted a ‘patrol vessel named “KAAMIYAB” to the Maldives’ as part of the Modi government’s efforts to embrace maritime regional security through the India-Maldives partnership (The Economic Times, 2019). Both leaders have ‘jointly inaugurated the Composite Training Facility of the Maldives National Defence Force in Maafilaafushi, and the Coastal Surveillance Rader System by remote link’ (Ministry of External Affairs, 2019b). In November 2020, the Maldives also resumed its participation in the India-Sri Lanka-Maldives National Security Advisor-level Talks. These security talks had been stalled during the last 6 years because of the worsening Maldives-India relations during former President Yameen’s term. This revival of subregional security talks has further anticipated the Maldives’ endorsement of India’s strategic step-up as a regional security provider.

Shared Ideas and Maldives’s Role in Balancing Security Issues

India’s step-up in defence and strategic cooperation has brought the Maldives closer to its broader Indo-Pacific security space in South Asia. India has a key role as the net security provider in its region particularly with respect to China’s influence in South Asia’s maritime states like the Maldives. President Solih’s decision to review the development cooperation and investments with China demonstrated an alignment of his political ideas with India’s view that China’s regional engagements must be kept under check (Rehman, 2009). Although Solih’s government has not seen China as security threat to the Maldives, his foreign policy has nevertheless lessened China’s influence in the Maldives. This policy has allowed the Maldives to play a crucial role in the Indo-Pacific security space by supporting India’s containment strategy against China and enhancing India’s defence engagement in the maritime boundaries.

The Maldives-India defence and security partnership can enhance the Maldives’ strategic role in Indo-Pacific security space. However, this role depends on the domestic political ideas. President Solih’s government has adopted a pro-India foreign policy. The former government’s pro-China approach led to the deterioration of Maldives-India relations during the period 2013 to 2018. This is an important consideration that can influence strategic thinking and political practices moulding present and future relations between the two states.

Constructivists argue that shared ideas can shape mutual understanding between states. Which brings ideas at the forefront of building alliances. Despite the size and material powers of states, ideas can shape inter-state cooperation and competition during crisis and change (Flockhart, 2016; Rasheed, 2020). In this respect, India’s step-up in maritime defence and security cooperation programmes was to a significant extent shape by the Maldives’ recent desire to shift regional policy interests towards India. One can argue that this alliance is sustainable only to the extent that the political ideas of both the states remain aligned and consistent—i.e. the domestic political ideas in the Maldives should adhere to ‘India First’ policy. This means that Maldives-India step-up in defence cooperation is guaranteed to the extent that the political purposes and choices of the Maldives called for a regional agenda that actively supports India’s efforts in curbing China’s expansion.

In this respect, a future change of government or local political thinking in the Maldives can take a more passive approach to regional security cooperation by focusing more on development cooperation, as it did during President Yameen’s term. Yameen did not cut diplomatic ties with India when his government enhanced development investments with China (Rasheed, 2020). His political ideas promoted the Maldives’ national development objectives, the fundamental aspects of which have not changed even in the current politico-economic system. As a SIDS the Maldives has been— and is still—dependent on foreign aid for its development process. China’s BRI offered a finance and investment opportunity for Yameen’s government to deliver its political and economic policy objectives. Yameen’s unwillingness to join India’s campaign to curb the Chinese expansion in the region was therefore merely driven by his pro-China development policy ideas and not based on a security agenda.

The shift in policy interests towards India since Solih’s government also illustrates the way changing political ideas have shaped the new government’s foreign policy in driving a renewed Maldives-India regional security cooperation effort. However, the future direction of the domestic political choices will determine the role the Maldives will play as a strategic ally of India. This may be argued considering the fact that Maldivians can always re-establish closer ties with China if a future government is less motivated to play a leadership role in regional security. Such policy shift is also likely to occur if a future government is more politically secure and stable. If this were to happen, the Maldives may potentially create uncertainties for Indo-Pacific security space.

Conclusion

India must play a key role within Indo-Pacific security space to ensure regional security in South Asia and surrounding maritime boundaries. The Indo-Pacific security space has been developed as a response to the growth of extra-regional powers (particularly China’s) in India’s maritime sphere of influence. This approach to regional security is a fundamental aspect driving the power dynamics and geostrategic competition between India and its regional maritime partners. The Maldives has been one of India’s closest regional maritime partners, and the bilateral relationship between the two is built of mutual trust and neighbourly bonds. However, the way in which the Maldives has formed regional alliances with extra-territorial powers, such as China, have had a significant impact on India’s capacity to fully manage regional security within the Indio-Pacific security space.

Since the launch of the BRI, the Maldives has strengthened its relationship with China to support its development efforts. However, China’s economic engagement has also brought it closer to India’s sphere of influence and created geostrategic competition between the two, challenging India’s capacity to sustain traditional security norms and customs followed by its Indo-Pacific partners.

As this article has demonstrated, the Maldives can influence regional power dynamics concerning India and China. This is explained in the context of political ideas and nature of policies adopted for development cooperation between the Maldives, China and India. Solih’s government generated ideas to renew cooperation with India and review China’s engagement with the Maldives. This created an opportunity for India to enhance bilateral ties especially maritime defence cooperation with the Maldives. This has also made the Maldives important player in the Indo-Pacific security space as far as India is concerned. The Maldives can act as a significant influencer in shifting geopolitical competition between regional powers.

References

Avas (2020). Radar systems, MNDF Composite Training Center inaugurated. Avas. Retrieved from https://avas.mv/en/65083

Baruah, Darshana M. (2020) India in the Into-Pacific New Delhi’s Theater of Opportunity. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/06/30/india-in-indo-pacific-new-delhi-s-theater-of-opportunity-pub-82205

Das, K. C. (2017). The making of One Belt, One Road and dilemmas in South Asia. China Report, 53(2), 125–142.

Flockhart, T. (2008). Constructivism and Foreign Policy. In S. Smith, A. Hadfield, & T. Dunne (Eds.), Foreign Policy: Theories, Actors, Cases. UK: Oxford University Press.

Joshi, R. (2018). View: China testing India’s resolve in Maldives. The Economic Times, Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/def ence/view-china-testing-indias-resolve-inmaldives/articleshow/63135488.cms

Laskar, Rezaul H (2020). India makes China point, US hints at ‘formal’ Quad. Hindustan Times, Retrieved from https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-makes-china-point-us-hints-at-formal-quad/story-c7ptK8v8MgDygLojE5s6oK.html.

Maldives Independent (2015). President Yameen’s speech on 50 years of UN membership. Retrieved from https://maldivesindependent.com/politics/presid ent-yameens-speech-on-50-years-of-unmembership-120410

Miadhu (2020). Male’-Vilimale bridge mashroou ah India in hiley ehee dhinumuge MoU eh gai soikohfi. Miadhu, Retrieved from https://mihaaru.com/news/82728

Miglani, Sanjeev and Junayd, Mohamed (2018). India’s Modi embraces Maldives as new leader takes office, China out of favour. Reuters, Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-maldives-politics-analysis-idUSKCN1NL1E8

Ministry of External Affairs (2018). Prime Minister’s Keynote Address at Shangri La Dialogue (June 01, 2018). Retrieved from https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/29943/Prime+Ministers+Keynote+Address+at+Shangri+La+Dialogue+June+01+2018

Ministry of External Affairs (2019a). India-Maldives bilateral relations. Retrieved from https://mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/Maldive2020.pdf

Ministry of External Affairs (2019b). India-Maldives Joint Statement during the State Visit of Prime Minister to Maldives. Retrieved from https://mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/31418/IndiaMaldives+Joint+Statement+during+the+State+Visit+of+Prime+Minister+to+Maldives

Ministry of External Affairs (2019c). Joint Statement on the Official Visit of Minister of External Affairs of India to Maldives. Retrieved from https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/31166/Joint_Statement_on_the_Official_Visit_of_Minister_of_External_Affairs_of_India_to_Maldives

Ministry of Foreign Affair of Japan (2018). International situation and Japan’s diplomacy in 2018. Retrieved from https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/other/bluebook/2019/html/chapter1/c0102.html#sf01

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (2014). The Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence. Retrieved from https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjb_663304/zwjg_665342/zwbd_665378/t1179045.shtml

President’s Office (2014a). Joint press communique between the Republic of Maldives and the People’s Republic of China, 15 September 2014, Male’.

President’s Office (2017a). Unofficial Translation of the Independence Day Remarks by His Excellency Abdulla Yameen Abdul Gayoom, President of the Republic of Maldives.

Rasheed, A. A. (2018). Ideas, Maldives-China relations and balance of power dynamics in South Asia. Journal of South Asian Studies, 6(2).

Rasheed, A. A. (2019). Can the Maldives Steer Regional Power Politics? E-International Relations. Retrieved from https://www.e-ir.info/2019/01/30/can-maldives-steer-regional-power-politics/

Rasheed, A. A. (2020). ‘Drivers of the Maldives’ Foreign Policy on India and China.’ In Navigating India-China Rivalry: Perspectives from South Asia. South Asian Discussion Papers. Retrieved fromhttps://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/papers/navigating-india-china-rivalry-perspectives-from-south-asia/

Rasheed, A. A. (2020). Climate Ideas as Drivers of Pacific Islands’ Regional Politics and Cooperation. E-International Relations. Retrieved fromhttps://www.e-ir.info/2020/01/15/climate-ideas-as-drivers-of-pacific-islands-regional-politics-and-cooperation/

Rej, Abhijnan (2020) India Welcomes US-Maldives Defense Cooperation Agreement in a Sign of Times. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2020/09/india-welcomes-us-maldives-defense-cooperation-agreement-in-a-sign-of-times/

Rehman, Iskander (2009) Asian Security, Vol. 5, No. 2, April 2009: pp. 1–21 Asian Security Keeping the Dragon at Bay: India’s Counter-Containment of China in Asia India’s Counter-Containment of China in Asia Asian Security. Asian Security, 5(2), 114–143.

South China Morning Post (2018). Maldives looks to ‘long lost cousin’ China, despite ‘brother’ India’s concern. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacydefence/article/2138504/maldives-looks-longlost-cousin-china-despite-brother

State Council of PRC (2014). China’s foreign aid (2014). Retrieved from http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2014/08/23/content_281474982986592.htm.

The Economic Times (2018). PM Modi arrives in Maldives to attend President-elect Ibrahim Mohamed Solih’s inauguration.Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/pm-modi-arrives-in-maldives-to-attend-president-elect-ibrahim-mohamed-solihs-inauguration/articleshow/66667500.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

The Economic Times (2019). India gifts patrol vessel to Maldives as net security provider of region. Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/india-gifts-patrol-vessel-to-maldives-as-net-security-provider-of-region/articleshow/72376730.cms

Tiezzi, S. (2018). China to India: Respect Maldives’ Sovereignty. The Diplomat. Retrieved form https://thediplomat.com/2018/02/china-toindia-respect-maldives-sovereignty/

Xinhuanet (2017) “Work Together to Build the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road”: Speech by H.E. Xi Jinping President of the People’s Republic of China At the Opening Ceremony of The Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation on 14 May 2017. Retrieved from http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-05/14/c_136282982.htm

Zhang, Yanbing and Huang, Ying (2012) ‘Foreign Aid: The Ideological Differences between China and the West’, Contemporary International Relations 22(2).

Zhang, Yanbing, Gu, Jing and Chen, Yunnan (2015). Rising Powers in International Development: China’s Engagement in International Development Cooperation: The State of the Debate. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/237086116.pdf

Wendt, A. (1992). Anarchy is what states make of it. International Organization 46, 394–419.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – With the Rise of the ‘Indo-Pacific’, Has the ‘Asia-Pacific’ Faded Away?

- Opinion – Emerging Patterns of Trade in the Indo-Pacific

- US Sanctions against Iran and Their Implications for the Indo-Pacific

- India’s Indo-Pacific Strategic Outlook: Limitations and Opportunities

- Opinion – The Coming of Age of the European Union’s Indo-Pacific Strategy

- Should There Be a New Grouping for the “Non-Nuclear Five” of South Asia?