This is an excerpt from Remote Warfare: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Get your free download from E-International Relations.

On 13 March 2019, the US Senate passed a resolution intended to bring an end to US support for the Saudi-led military campaign in Yemen. For nearly four years, the US had supported its ally with equipment, intelligence and logistical support amidst a growing record of large-scale civilian casualty incidents and in the wake of a mounting human toll from the conflict. But with each report or photo of the devastation wrought by the Saudi-led campaign, and the murder of Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi, cracks began to emerge in the long-held assumption that the strategic partnership was immune to American public concerns about the Kingdom’s human rights record. While the Senate’s vote on Yemen is one of the more recent, and the most notorious cases, it is one of many circumstances in which American strategic interests have been compromised by insufficient attention given to the risks of civilian harm – and to including civilian casualties, human rights abuses and humanitarian crises either created by, or associated with, its security cooperation and security assistance activities.[1]

The case of support to Saudi demonstrates one way in which the United States Government may encounter a policy obstacle, in the form of public scrutiny, that results from harmful policies and practices of a partner over which it has little or no control. But civilian harm and human rights violations committed by America’s partners can also undermine progress toward the security interests that security cooperation is intended to achieve in more fundamental ways. For example, human rights abuses by a partner can counteract joint efforts to counter terrorism by eroding the public’s trust in the legitimacy of the partner state (and by extension, the United States), or even by increasing the number of the disaffected who may turn to violence in response to state-sponsored abuse (UNDP 2017, 5, 80). Meanwhile, providing security assistance in fragile states, where such harms may be more likely or prevalent, can also aggravate conflict, undermine stabilization, or counteract peacebuilding efforts (Kleinfeld 2018, 282–285). Finally, human rights abuse or civilian harm may be symptomatic of larger institutional deficits or structural phenomena (e.g. corruption) that greatly diminish the likelihood that security cooperation will ever achieve its desired outcomes.

Having a sounder understanding of risks specific to human rights and civilian harm could, at minimum, allow the US government to optimise the desired returns on security cooperation with fewer attendant costs. This chapter sets out a summary of a framework developed by Center for Civilians in Conflict, by which the US – and even other states or institutions – might assess the human rights and civilian harm risks involved with undertaking security cooperation activities with particular partners. It also presents a selection of factors to consider in the design of the partnership to ensure ‘interoperable’, i.e. compatible, approaches to risk mitigation. As such, the US Government might use the framework in one of three ways: 1) ex ante policy analysis of its partners to help formulate security cooperation strategies; 2) ongoing analysis of risks that can be used to head off significant problems arising from harm or to monitor progress or improvements; and 3) a means of designing and customizing risk mitigation measures specific to, and appropriate for, partnerships of vastly different character.

Scope of Application

For purposes of this analysis, security cooperation can include a variety of activities along a spectrum of involvement, from partnered operations involving both countries in the military or security operations, to the provision of advice, operational or logistical support, arms sales, and training and education (Knowles and Watson 2018, 3) . While partnership with civilian law enforcement may be implicated by this framework, and certain analytical criteria may apply to police activities, the analysis is primarily geared toward application to cooperation between, and with, military forces. Meanwhile, the framework is based on the hypothesis that security cooperation can correspond directly or indirectly with human rights or civilian harm (which may or may not be per se lawful) in one or more ways, inter alia:

- Assistance may directly enable harm caused independently by the partner (e.g. missiles sold by the US are used to strike hospitals, or a unit trained by the US commits a mass atrocity)

- Assistance, provided over time, may more generally enhance the lethality of a partner force in a vacuum of appropriate constraints

- Assistance may distort, or exacerbate, the distortion of defence or security priorities (thereby depriving civilians of needed security services)

- Support or assistance may abet harm as a direct result of jointly conceived or planned activities or operations (e.g. the US acts on intelligence from a partner that yields a targeting error and civilian casualties)

- Assistance or materiel provided in the absence of adequate controls may be diverted to other groups or individuals who subsequently harm civilians

- Support or assistance may occur independently, but incidental to significant forms of harm (the US sells major military equipment to a country with an abusive police force)

- Support to security forces with a record of human rights abuses or civilian harm in the absence of accountability risks tolerating or even endorsing impunity

- Acts of security cooperation may elevate the tolerance threshold of risk for human rights abuses or civilian harm (e.g. the US pressures a partner to act more assertively in a military operation)

Limitations on Current Approaches to Risk Management

The United States government does, by all accounts, take human rights and civilian harm risks into consideration as it plans and implements its security cooperation activities. However, while the constituent elements of its current approach to risk management are each independently worthwhile, they may not together constitute an approach that is optimally designed for both anticipating and managing risks. Restrictions on assistance based on past conduct, and especially conduct related to human rights violations (such as through the US ‘Leahy Laws’[2]) can be effective for reducing material support to specific units who have already committed violations. But examining the risk of partnership on the basis of past conduct may not adequately consider variables that relate to the likelihood of harm in the future. Meanwhile, leaning on legal analysis to ensure an act of support is technically ‘lawful’ under its own interpretation of obligations under state responsibility may have little bearing on the practical effects of harms experienced by civilians and may not comport with public or even international perceptions of lawfulness or legitimacy (Shiel and Mahanty 2017, 9).

Moreover, technical assessments of competencies or capability gaps, may not adequately consider legal, political, or other environmental factors that may have a significant bearing on the likelihood of human rights abuses or civilian harm, and in so doing, may ignore the interaction between variables at the political and operational – or even tactical – levels. Although certain institutional variables may proxy for other kinds of risks (e.g. inadequate legal safeguards may represent operational risk of human rights violations) and are therefore worthy of attention, attending to the risk of partnership with a focus on one category of analysis at the expense of others can lead to narrowly conceived solutions which fail to address the source of risk. Finally, attempts to reduce risk through purely technical interventions like training, or the provision of less than lethal equipment or precision weapons may yield some positive benefits under certain conditions, but may not overcome institutional deficiencies or overcome overriding political incentives that enable harm to occur (Dalton et al. 2018, 23).

In diagnosing risks, and in designing measures to mitigate them, an overly narrow scope of application can carry unintended consequences. First, policymakers may over-estimate the extent to which any one safeguard actually mitigates the most pressing risks (e.g. the government may defend its support to a partner based on its confidence in the capacity for human rights training to overcome gaps in accountability). Second, the government may overlook opportunities to achieve the intended outcome of a security cooperation activity while also managing the risk through more proactive, and effective controls. Finally, any of these approaches may fail to account for the way a cooperative relationship, and the context in which it exists, can change over time.

A Framework of Analysis for Civilian Harm and Human Rights Risks in Security Cooperation

To establish a more suitable approach to managing the different kinds of risks associated with different kinds of security cooperation, policymakers, program managers and those who evaluate government practices from the outside, might look toward a new framework of analysis that establishes the basis for designing programs with adequate controls and safeguards in place. A well-designed framework would 1) align with the emerging policy consensus about the necessary components of effective and sustainable security cooperation programs; 2) identify the variables within several categories of analysis (e.g. political, legal, and operational) that correspond with the risks most worthy of attention; 3) allow for customised application to a specific security cooperation activity; 4) consider the risks that derive both from the ‘partner’ as well as from the ‘acts of partnership’, and 5) lend itself to relatively clear policy prescriptions that flow from the diagnosis it presents.

Each category of risks in the framework that follows includes a sample of representative risk indicators, along with an associated claim about how any perceived or deal deficits may impair the government’s ability to achieve a desired end-state with its partner. Ideally, the government could use the framework to make policy decisions about the viability of partnership (e.g. as prerequisite conditions); to design and modify partnership activities; and to prioritise and integrate risk mitigation measures. Among options that may be considered in response to analysis conducted on the basis of this framework, policymakers or program managers might consider moderating or reducing any forms of assistance that materially enhance the lethality of security forces (Kleinfeld 2018, 283–285). The government may also elect to sequence support or establish pre-requisite requirements (e.g. demonstrating a particular competency) prior to providing certain kinds of assistance or partaking in certain kinds of partnership activities; (Shiel and Mahanty 2017, 32), or to require more direct oversight (‘operational end-use monitoring’) (Lewis 2019, 28) of operations that benefit from support or assistance.

Political Factors

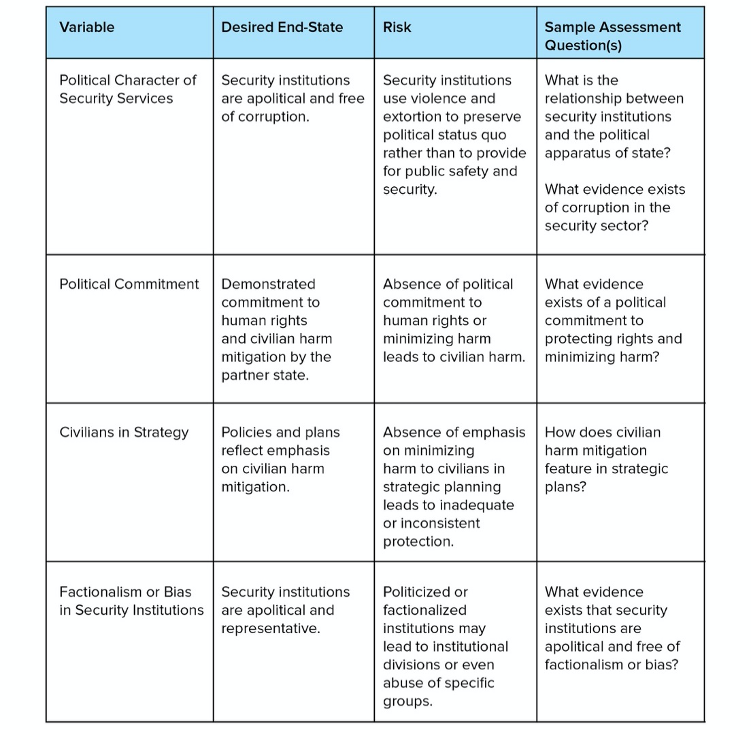

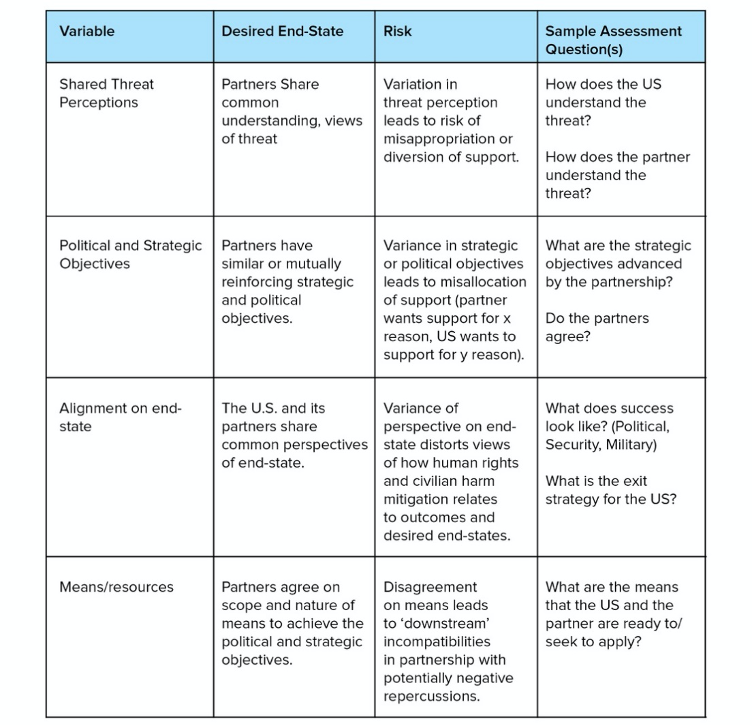

The political context in which security partnerships take place has direct and inextricable bearing on the risk of human rights or civilian harm in at least three discernible ways. First, security relationships between states are shaped by, and bound to, the alignment or misalignment of political intentions and objectives of each state (Tankel 2018, 308–310). When objectives are misaligned, a state risks participating in security operations that do not serve its core interests, but also partially ‘owns’ any negative consequences (Rand 2018). As importantly, the political organisation of the state and the political orientation of its security forces carry significant implications for the ways in which the state employs the use of violence (e.g. in the violation of human rights). When a state such as the United States enhances the capacity of state security institutions, they are better able to serve whatever political purpose they ultimately serve (Kleinfeld 2018, 284). If state security forces have been instrumentalised to preserve the economic or political power of a rent-seeking elite, then the security forces may in turn instrumentalise the use of force in service of that objective. In these cases, enhancing the capacity of the state may contribute to the state’s hold on the monopoly on the use of violence, but in service of illegitimate ends.

The extent to which the political character of security institutions should and can affect the assessment of human rights and civilian protection risks largely depends on the type of cooperation activity and the scale of divergence between the status quo and a desired end state. Indicators in this category are most useful during policy deliberations about whether, and how much, the United States should pursue its foreign policy aims through security cooperation activities.

Figure 1: Political/Strategic (partner State)

Figure 2: Political/Strategic compatibility

Security Governance Factors

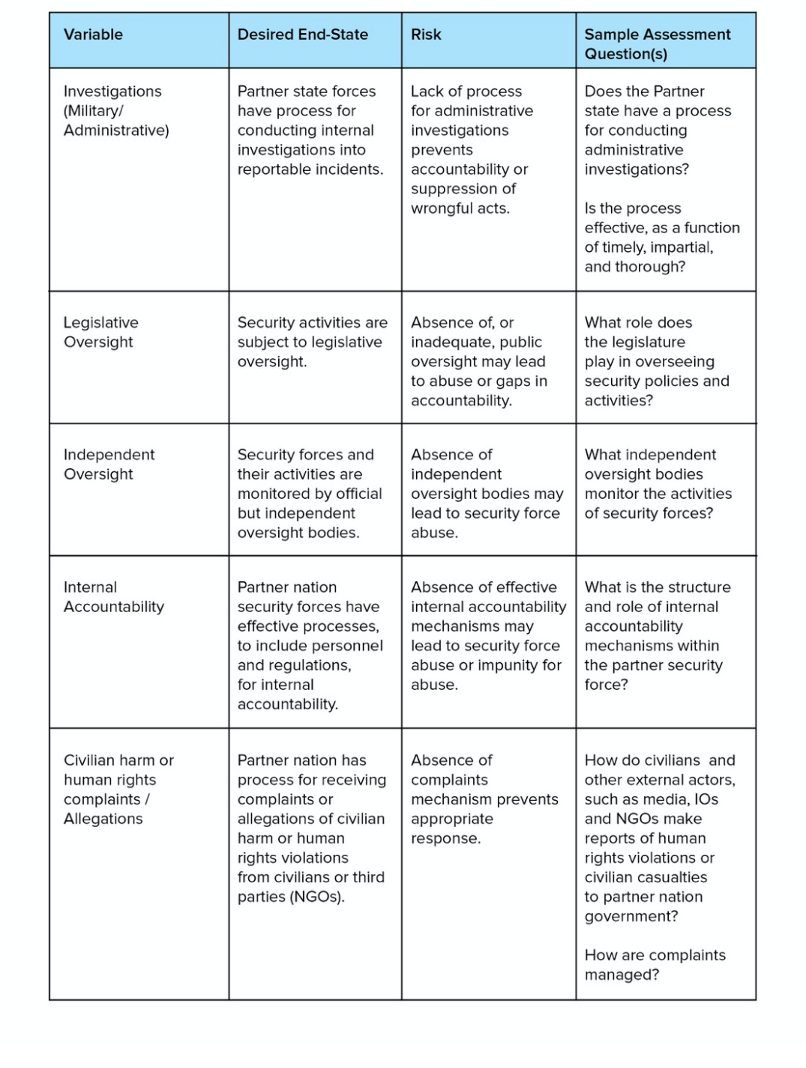

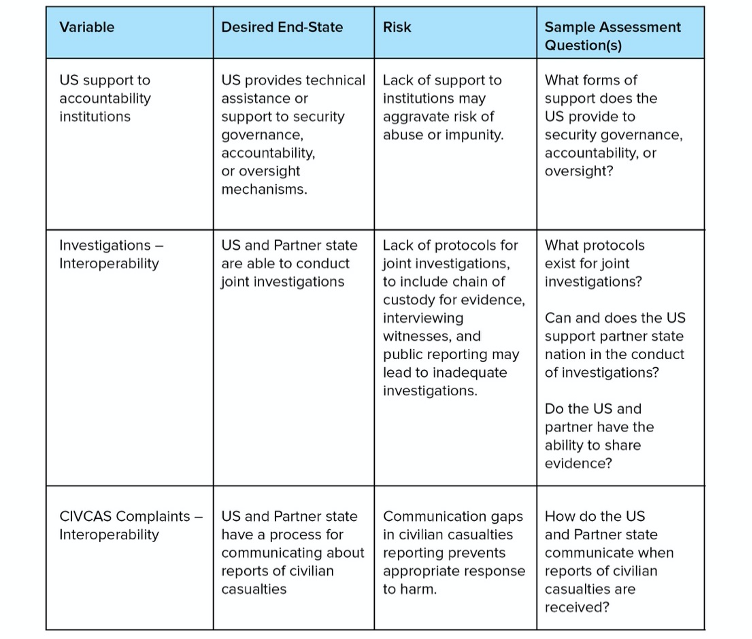

The proclivity of security forces to engage in human rights abuse or conduct that results in harm may also depend on the extent to which security institutions are subject to appropriate constraints in the form of internal controls, external oversight[3] and accountability measures (DCAF 2018, 7–10). While the methods and means of exercising oversight and accountability of security forces may vary depending on the circumstance, they should work together to ensure the prevention of and accountability for human rights violations and should work to rectify shortcomings in security governance. Partnering with, or supporting, a state’s security forces that operate in a vacuum of accountability and oversight increases the risk that the assistance could directly lead to abuse or harm. There is also the risk that the providing state will become associated with harm to which it has made no explicit contribution (Goodman and Arabia 2018, 33–35; Shiel and Mahanty 2017, 31).

While it is important to evaluate the institutional makeup of the partner forces and the oversight bodies that govern them, it is equally important to assess the extent to which the partnership itself is subject to oversight and accountability. For example, it may be appropriate or prudent to subject certain features of a partnership to parliamentary oversight to ensure a degree of ‘informed public consent’, even if such arrangements are not bound by treaties requiring parliamentary approval. Indicators within this category are most useful during policy deliberations, but also in determinations of the kinds of cooperation the US may be willing to undertake – or should avoid, such as lethal assistance – given any major institutional deficits.

Figure 3: Security Governance – accountability and oversight

Figure 4: Security Governance interoperability

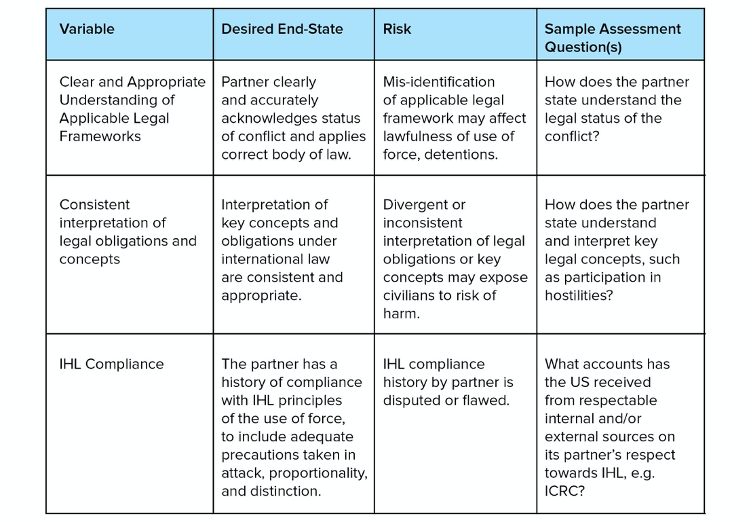

Legal Compliance and Interoperability Factors

Questions related to the interaction between security cooperation and international law fall loosely into two broad and distinct, but related, categories. The first category includes questions that relate to the obligations each state has under international law, how the cooperation activity accrues responsibility to each for their own action and how each might share responsibility for the actions of the other. The degree of legal liability imparted to states that participate in security cooperation activities largely depends on the applicable legal theory of state responsibility (and how it is being interpreted), and may depend on the nature and significance of the action, and whether and how much a state ‘knows’ about any internationally wrongful acts it is supporting. [4] This category of concerns also raises questions about any gaps that are created with respect to attribution and accountability for actions among states in ‘coalitions of the willing’ (Tondini 2017, 11–13). Common Article 1 of the 1949 Geneva Conventions also obliges states to ‘undertake to respect and to ensure respect’ for international humanitarian law (IHL), which could, in theory, create an additional obligation on states to promote respect for IHL through both positive and negative means available.

Figure 5: Legal (partner state)

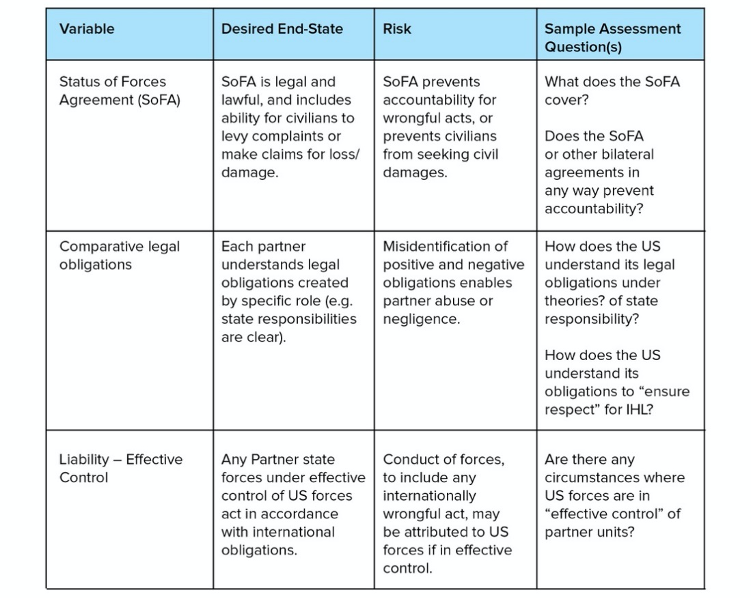

Other questions relate to the degree of ‘legal interoperability’[5] between the partnering states that ensures compatible interpretation and application of the law (Goddard 2017, 211, 212). Legal interoperability might also include a consideration for how any formal or informal legal arrangements dilute or strengthen accountability to the law, e.g. in the form of status of forces agreements that relieve one of the states of accountability (Hussein, Moorehead and Horowitz 2018). Indicators in this category may be most useful for circumstances in which the US is providing operational support or is involved with the partner in joint operations (so-called ‘partnered operations’).

Figure 6: Legal interoperability

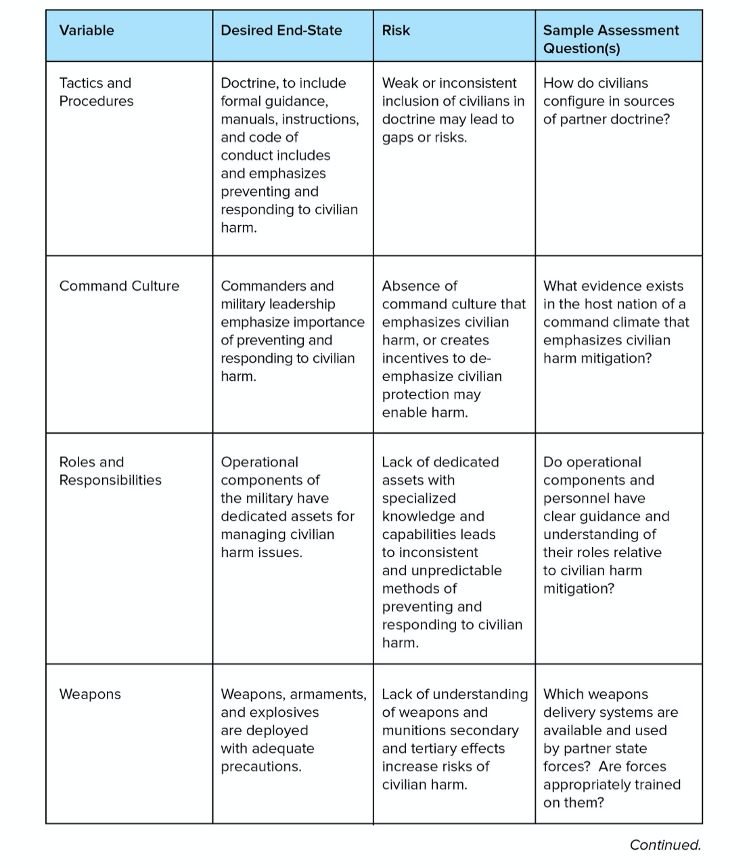

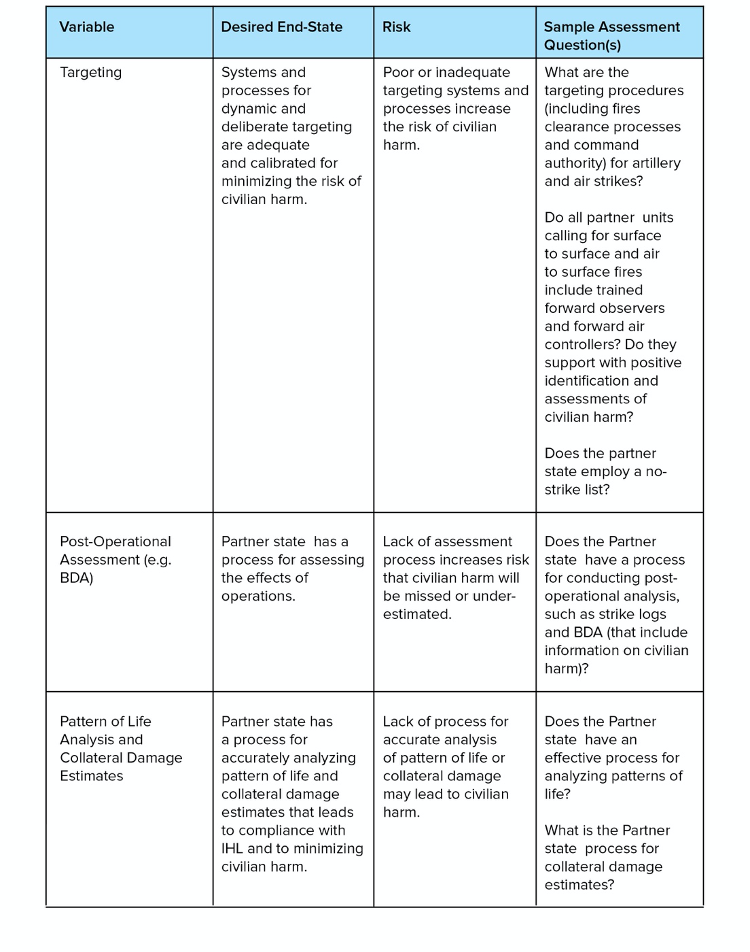

Operational Factors

Operational capacity is unlikely to overcome factors at the political level that enable, encourage or tolerate human rights abuses. But some degree of tradecraft competency is necessary for translating a political commitment to protecting rights or preventing harm into operational reality. In the case of law enforcement operations, police, or security forces acting as police, can avoid or reduce harm through tactical proficiency in escalation of force or the effective use of non-lethal methods (OHCHR 2004, 27). Similarly, military forces can take meaningful steps toward preventing, mitigating, and responding to any ham they cause in the course of their own operations during the conduct of hostilities (Lewis 2019, 38). (Note: the small selection of sample variables here applies to military operations and civilian harm, rather than law enforcement activities and human rights. They are meant to be representative of the kinds of variables that may be appropriate.)

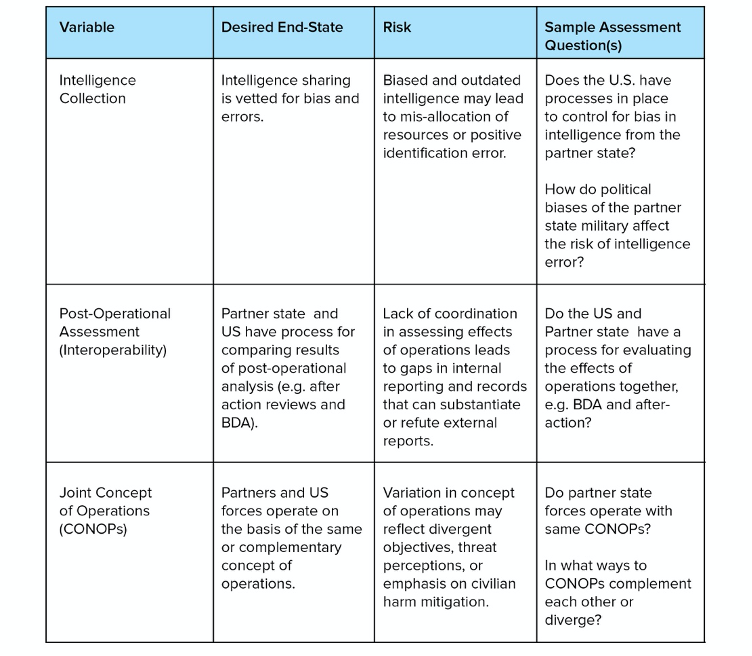

Figure 7: Operational

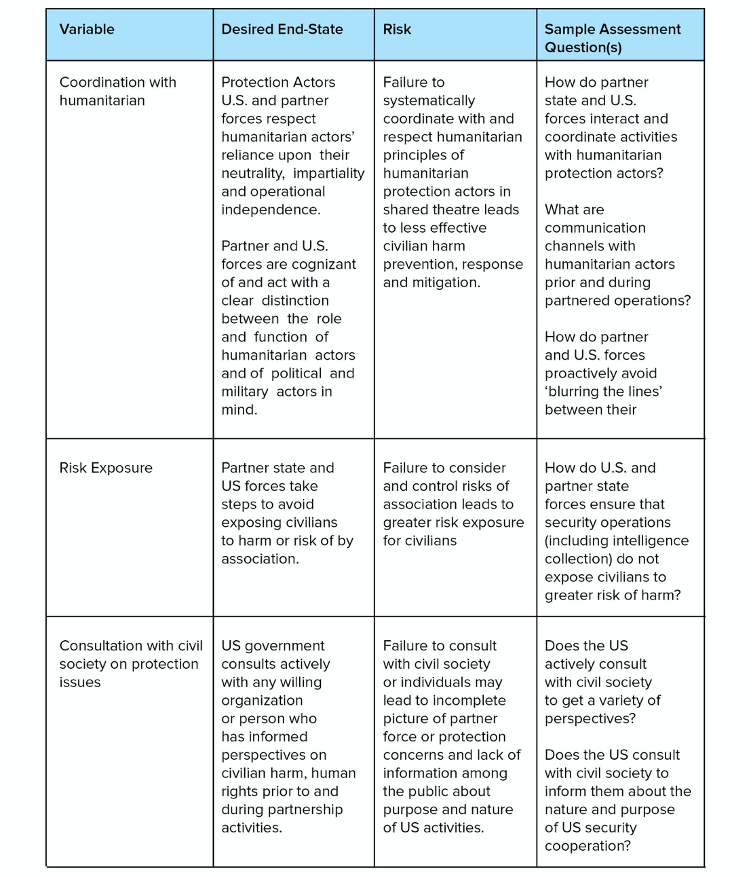

Similar to the other categories within this framework, operational risks derive not only from the characteristics of the partners, but also from the acts of cooperation they undertake. Just as risks can emerge from variations in the understanding and application of law, so too can they stem from gaps in interoperability in joint or partnered security operations, to include the ways in which partners plan, prepare, and execute missions, and in the ways in which they respond to allegations or reports of harm or abuse (Dalton et al. 2018, 20). When providing materiel or logistical support, the US may benefit from ensuring it is able to undertake ‘operational oversight’ (or ‘operational end-use monitoring’) so that it can better understand the nature of the military activities it is supporting. (Lewis 2019, 28).

Figure 8: Operational interoperability

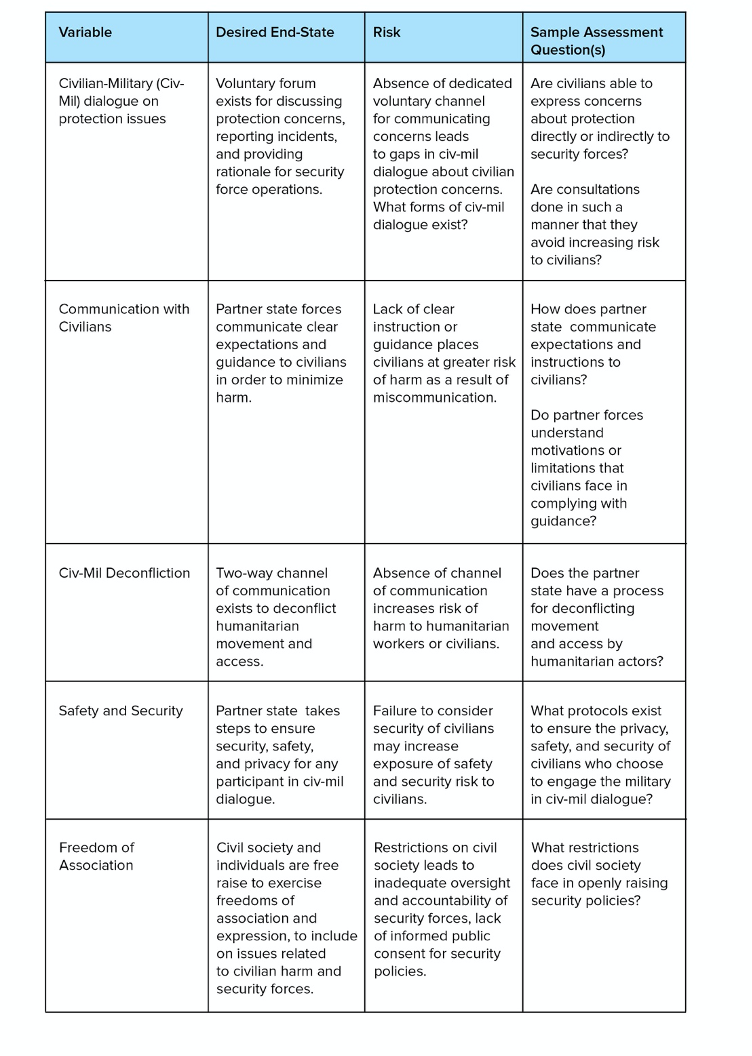

Civil-Military Relations and Civil Society Factors

Finally, the risk of civilian harm or human rights issues can be managed through constructive and meaningful interaction between security forces and civilians, to include the consideration of civilian perspectives in the design and implementation of security cooperation activities. Two broader categories of engagement are particularly germane to this framework. The first is the capacity of either, or both, partners to engage in effective civil-military relations in the context of security operations, which includes having channels available for understanding and responding to community protection needs, to include the risks faced by civilians; and the degree to which the military and the public have a shared understanding of ‘security.’ Important to the analysis are the ways in which security forces communicate with civilians in advance of, during and after operations and the extent to which the military avoids creating or transferring risks to civilian populations through certain activities. These can include seeking intelligence, maintaining an active presence near civilians, or failing to consider safety, security, or privacy of the communities or individuals with whom they engage.

Figure 9: Civil-military and civil society

The second category of criteria that can be pertinent to the design of security cooperation is the role and functionality of civil society as both a source of public oversight of security force activities, and a potential signal of informed public consent to partnership arrangements (Dalton et al. 2018, 12). Governments undertaking security cooperation activities should be wary of tacitly encouraging or abiding by cases in which the partner government has placed explicit, or implicit, restrictions on civil society and its ability to act as a meaningful check on government activities. In some cases, civil society, for political reasons or otherwise, may not be present, active, or coordinated to engage government on security policy. In these cases, the United States should ensure that it seeks meaningful and voluntary input from sources that can serve as a proxy – or it should calibrate its activities to account for the additional risk imposed by the lack of civil society as a meaningful check.

Figure 10: Civil-Military interoperability

Conclusion

Even as the US Government shifts its stated defence priorities toward ‘great power competition’, and reduces the numbers of its own forces from theatres such as Afghanistan and Iraq, the era of security partnership, and the emphasis on ‘by, with, and through’ is likely here to stay. If anything, as great powers seek to avoid the devastation of direct confrontation by competing through more indirect means, the range and scale of security cooperation activities and security assistance may actually increase. In the absence of the proper controls, these activities may run the risk of distorting local systems of governance, exacerbating corruption, or contributing to human rights abuse.

The mere availability of a more organised set of risk indicators will not automatically generate the appropriate policy response now, or in the future, until policymakers recognise the importance of taking human rights and civilian harm more seriously when designing and implementing security cooperation and assistance activities. After all, the US government was not oblivious to the human rights record of its Saudi partners, nor unable to diagnose gaps in its interest or capacity to avoid civilian harm using US-manufactured weapons. Even so, a more comprehensive framework of analysis may assist policymakers and security cooperation program managers in anticipating problems before they arise, compelling clear policy choices, and in identifying the areas where mitigation measures are best placed throughout the life cycle of a partnership.

Notes

[1] A note on terminology: While security cooperation and security assistance have different definitions in sources of US Government guidance, this paper will use the term ‘security cooperation’ to include security assistance activities for purposes of simplicity.

[2] For background on the Leahy Laws, see: ‘Leahy Law’ Human Rights Provisions and Security Assistance: Issue Overview. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R43361.pdf

[3] According to DCAF, ‘Oversight is a comprehensive term that refers to several processes, including ex-ante scrutiny, ongoing monitoring, and ex-post review, as well as evaluation and investigation. Oversight of security services is undertaken by a number of external actors, including the judiciary, parliament, National Human Rights Institutions (NHRI) and ombuds institutions, National Preventive Mechanisms (NPM), audit institutions, specialised oversight bodies, media and NGOs. Oversight should be distinguished from control as the latter term implies the power to direct an organisation’s policies and activities. As such, control is typically associated with the executive branch of government.’ (DCAF, 6)

[4] See Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, ILC Yearbook 2001/II (2)(ARSIWA or Articles on State Responsibility), Articles 6, 16, 17, and 47. http://legal.un.org/ilc/publications/yearbooks/english/ ilc_2001_v2_p2.pdf.

[5] Defined by the International Committee of the Red Cross as ‘a way of managing legal differences between coalition partners with a view to rendering the conduct of multinational operations as effective as possible, while respecting the relevant applicable law.’ International Committee of the Red Cross, International Humanitarian Law and the Challenges of Contemporary Armed Conflicts: 32–33.

References

Beittel, June S., Lauren Ploch Blanchard, and Liana Rosen. 2014. “Leahy Law” Human Rights Provisions and Security Assistance: Issue Overview. Congressional Research Service.

Dalton, Melissa, Shannon Green, Hijab Shah and Rebecca Hughes. 2018. Oversight and Accountability in US Security Sector Assistance: Seeking Return on Investments. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Washington, DC.

Dalton, Melssa, Jenny McEvoy, Hijab Shah and Daniel Mahanty. 2018. The Protection of Civilians in US Partnered Operations. Policy, Center for Strategic and International Studies. Washington, DC.

DCAF. 2018. International Standards and Good Practices in the Governance and Oversight of Security Services. Policy, Geneva: Geneva Center for Democratic Control of the Armed Forces (DCAF).

Goddard, David. 2017. ‘Understanding the Challenge of Legal Interoperability in Coalition Operations.’ Journal of National Security Law and Policy, 9: 211–232.

Goodman, Colby, and Christina Arabia. 2018. Corruption in the Defense Sector: Identifying Key Risks to US Counterterror Aid. Policy, Washington, DC: Center for International Policy.

Hussein, Rahma, Alex Moorehead and Jonathan Horowitz.’Niger Facing Pressure to Ensure U.S. and French Drone Strikes Comply with Human Rights Law.’ Just Security. 6 September.

International Committee of the Red Cross. 2015. International Humanitarian Law and the Challenges of Contemporary Armed Conflicts.

Kleinfeld, Rachel. 2018. A Savage Order. New York: Pantheon.

Knowles, Emily, and Abigail Watson. 2018. Remote Warfare: Lessons Learned from Contemporary Theatres. Research, London: Oxford Research Group.

Lewis, Larry. 2019. Promoting Civilian Protection during Security Assistance: Learning from Yemen. Policy Washington, DC: Center for Naval Analysis.

OHCHR. 2004. ‘Human Rights Standards and Practice for the Police.’ Training, Geneva: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Rand, Dafna. 2018. ‘Extricating the United States from Yemen: Lessons on the Strategic Perils of Partnered Operations.’ Lawfare. 25 November. Accessed 1 June 2019. https://www.lawfareblog.com/extricating-united-states-yemen-lessons-strategic-perils-partnered-operations

Shiel, Annie, and Daniel Mahanty. 2017. With Great Power: Modifying US Arms Sales to Reduce CIvilian Harm. Washington, DC: Stimson Center and Center for Civilians in Conflict.

Tankel, Stephen. 2018. With Us and Against Us. New York: Columbia University Press.

Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States. 2019. Final Report of the Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States. Policy, Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace.

Tondini, Matteo. 2017. ‘Shared Responsibility in Coalitions of the Willing.’ In The Practice of Shared Responsibility in International Law, edited by André Nollkaemper and Ilias Plakokefalos: 701–732. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. UNDP. 2017. Journey to Extremism in Africa. Research. New York: United Nations Development Program, Regional Bureau for Africa.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Security Cooperation as Remote Warfare: The US in the Horn of Africa

- Business and Human Rights, Poverty and Power: Bridging the Political Economy Gap

- Opinion – The Path Beyond Trump in US Human Rights Policies

- Protecting the Protectors: Strengthening the Security of NGOs in Conflict Zones

- Opinion – Impacts and Restrictions to Human Rights During COVID-19

- Human Rights Reform in the UAE: Natural Socio-Political Evolution or Positional Strategy?