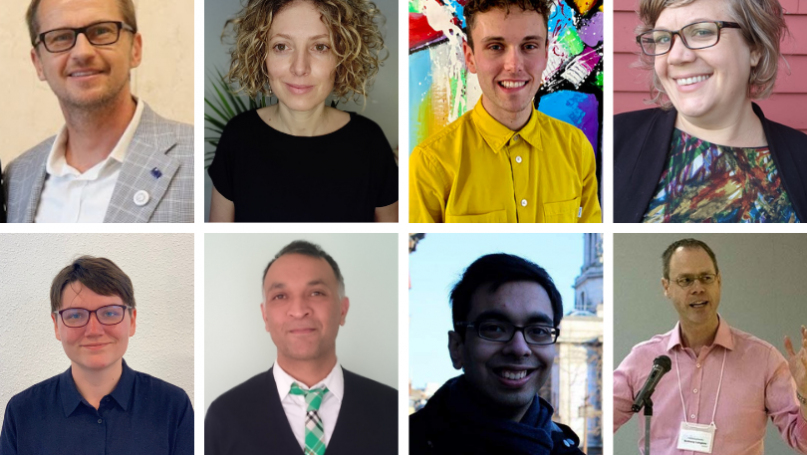

To celebrate LGBTQ+ History Month, we asked several scholars and previous contributors to E-IR: Do you think the discipline of IR has made important strides to equally incorporate LGBTQ+ perspectives, research, ideas and histories, both conceptually and institutionally? What could be done better? Below are responses from Melanie Richter-Montpetit, Ibtisam Ahmed, Markus Thiel, Ioana Fotache, Momin Rahman, Anthony J. Langlois, Jamie Hagen and Dean Cooper-Cunningham.

Dr. Melanie Richter-Montpetit is Lecturer in International Security at the University of Sussex and Director of the Centre for Advanced International Theory (CAIT). View Melanie’s interview with E-IR here.

LGBT and Queer IR research has grown tremendously over the past few years. I’m delighted that LGBT/Queer scholarship has not only flourished intellectually, but overall has made some important gains institutionally: That includes a steadily growing number of LGBT/Queer IR books published by university and prominent trade presses, and we now find LGBT/Queer articles published across IR journals, even in some of the more mainstream journals – I can barely keep up with all the new publications and that’s really exciting! The ISA-LGBTQA Caucus has been an important space in building community. Over the past five or so years, the Caucus has grown not just in terms of numbers but it has come to bring together a greater diversity of scholars and scholarship, and has turned into a vibrant hub for developing transnational research networks, for mentoring early career researchers and for providing a supportive social space for queer and trans scholars.

Acknowledging these important advances, it is striking however, how comparatively little institutional gains there have been across the discipline for transgender research and researchers. To begin to address the unevenness of institutional gains for LGBT/Queer scholarship, we must reckon in particular with longstanding transmisogyny. This is not ‘just’ a matter of the past. With the dramatic intensification of white nationalism across the globe, academic colleagues, including prominent senior IR scholars, have been driving a vicious campaign against transwomen, including very publicly on social media.

In this LGBT month, if we are serious about celebrating and supporting LGBT/Queer scholars and scholarship, we must tackle IR’s professional and material cultures. The dramatic increase in precarious employment and the proliferating attacks on academic freedom from within and outside the academy (incl. under rubrics like ‘woke’ and ‘cancel culture’) exacerbate the already profound hierarchies of the university as a site of learning, knowledge creation and employment. Alongside a general deterioration of working conditions, the rising impact of precarity and of attacks on academic freedom are compounded for multiple-oppressed scholars, in particular Black, Indigenous, lower caste, Muslim and women/femmes/trans of colour colleagues. No doubt these developments have fuelled existing relationships of material dependence and possibility for abuse, have produced structural incentives not to rock (too much) the boat of existing orthodoxies in both mainstream and critical IR, and led brilliant and engaged (LGBT/Queer) IR scholars to quit academia.

Finally, when taking stock of the important institutional gains LGBT/Queer IR research has made in recent years, it is important to consider what Malinda Smith (2018: 55) has termed “diversifying whiteness”, meaning the neoliberal academy responding to calls to tackle institutional racism by reframing the ‘problem’ as one of a general lack of ‘diversity’ and addressing it by including white women and white queer people. Reflecting on the (uneven) gains LGBT/Queer research and researchers have made in IR, it is imperative to reckon with how these advances might be entangled with the ‘diversification of whiteness’ both on the level of institutional inclusion and of knowledge frames (Alison Howell and I are discussing this in more detail in an upcoming article).

Ibtisam Ahmed is a Doctoral Researcher at the School of Politics and IR at the University of Nottingham. View Ibtisam’s contributions to E-IR here.

I think there are two distinct ways of looking at this question. From the perspective of it being a simple comparison with the past – yes, there have absolutely been strides in the field. There has been a general increase in engagement across disciplines with queer theory, and that has strengthened both queer theory and the subjects it interacts with. In the case of IR, this has led to a broadening of perspectives as a whole, especially because the central tenet of queer theory is that marginalised voices need to be actively centred and uplifted. As a discipline, IR has been part of an important global push towards better visibility, discussions and solidarity, and this should be applauded.

However, there is also a distinct gap in the ways in which IR practically supports queer lived realities. While the academic and conceptual embrace of queer perspectives has been phenomenal – though, I hasten to add, not perfect – there has been little to no effort in bringing that same openness to practitioners, policy makers and governments. Discrimination and violence against the LGBTQ+ community has increased across several contexts. Countries where homosexuality remain illegal, such as my own home in Bangladesh, has seen an uptick in violence and social prejudice that has been implicitly encouraged by the state. Supposedly progressive democracies like India and the UK have seen the entrenchment of systemic transphobia, legally in the former, and institutionally in the latter. Several right-wing governments like those in Brazil and Poland have clamped down on queer rights, and 2021 began with the news that Malaysia will pursue tougher censorship and sanctions against queer rights groups.

What this reflects is a problematic tokenisation of queer issues. They are an almost “trendy” cause to support and use to bolster credentials, especially when occasions such as History Month, Pride and IDAHoBiT are commemorated. Unfortunately, the community remains an expendable bargaining chip – useful one day for better press, discarded the next for uncomfortable diplomacy and foreign relations. The solution is, at its heart, quite simple. Queer communities and voices need to be centred the same way that queer theory has allowed their perspectives to be highlighted in the academy. And I specifically use the plural communities here because queer experience and politics is varied. When I contributed to the E-IR book Sexuality and Translation in Politics, I was exceptionally pleased at the international remit and diverse voices present, because there are so many different challenges and solutions facing us. If that same focus and platform is afforded in the practical implementation of IR, including a commitment to protecting the voices who speak up, I see the possibility of a hopeful future. In order to do so, those with privilege who want to call themselves allies need to do the work. After all, allyship is an action, not an identity. I hope that these reflections in LGBTQ+ History Month spur them into action.

(A note to readers – I realise that queer has a contentious history in the Anglo-centric world, but it provides a more nuanced and inclusive translation of non-Western identities than the LGBTQ+ acronym. It speaks to my lived realities as well as the breadth and richness of scholarship on the topic.)

Markus Thiel is an Associate Professor of Politics and International Relations at Florida International University. View Markus’ previous contributions to E-IR here.

As with most academic disciplines, IR has only slowly and hesitantly opened up to epistemological diversity among its theoretical approaches. Thinking of its precursor, feminist thinking was integrated into the discipline of IR earlier than LGBTQ+ studies or Queer Theory, but typically remains outside of the standard disciplinary canon. Many IR theory textbooks will likely include feminism and post-colonial theories, but not LGBTQ+ or Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (SOGI) ones – the open-access International Relations Theory book from E-IR thankfully does so. And just as feminism is still somewhat siloed off from mainstream IR, and internally divided, LGBTQ+ perspectives are likewise marginalized and generally split between more empirical LGBT studies and more challenging, transgressive Queer theoretical work. It is difficult to determine if the recent explicit focus on the inclusion of greater scholarly diversity has helped scholars working in these areas, or if they compete with other equally pressing racial and Global South prioritizations. As an illustration of this dilemma, the last candidate panel for the International Studies Association’s executive committee was more ethnically and globally diverse than ever, yet was criticized for its lack of gender balance.

Institutionally, LGBTQ+ studies may be seen as a peripheral research interest, not worthy of attention, publication or promotion, or they may be regarded as a subject too personal and thus, lacking supposed standards of ‘objectivity’ that are still the norm in IR. These considerations make it harder for scholars to obtain tenure, or engage more broadly with fellow researchers in the field. Hence to continue the integration of those underrepresented foci, it is essential to change our discipline from within by walking the academic tightrope between conformity to disciplinary standards and policies, and critical transformation of those same policies. The last few years have been fruitful for this emerging field of study, with increased levels of student interest and high scholarly productivity and excellence. More inclusive principles and practices within higher education institutions are still necessary, however, so that scholars in the LGBTQ+ fields can flourish without marginalization or academic tokenism.

Ioana Fotache is a PhD candidate in the Socio-Cultural Doctoral Program at Nagoya University. View Ioana’s E-IR article here.

To begin with, I’m not sure what ‘my field’ is. I started out in gender studies, focusing on hetero literature with a queer approach, and to be honest that field has experimented an intense shift towards queer as non-LGBTQ, while also excluding non-cishet sexualities from women-targetted approaches. At one point, ‘queer’ became such a wide term that it encompassed too many things to leave room for ‘regular’ LGBTQ folks. The seminal approaches, based on psychoanalysis, were already ill-fit to handle trans people, for example, and the more the field progressed without addressing these issues, the more it went down an LGBTQ-exclusionary spiral. It has become very difficult to approach actual queer people and lives in this environment, especially if they’re non-binary or trans. I feel like we haven’t moved on since Jay Prosser (2003) critiqued the foundational exclusion of trans and non-binary people from queer theory, while also maintaining his conclusion that ‘even so, we like the idea of it’.

I moved to sociology to start anew and found it, oddly enough, freer to include a wider diversity of lives and sexualities, if you found the right professor. But again, it depends on your type of sociology. For example, I feel that quantitative approaches are still lacking in inclusion, due to their very nature. People rarely can give the answers a sociologist needs, in terms that are easily quantifiable and pattern-generating. There has been so much work done to include them, but it can still be difficult, and I fear that many would still shy away from tackling LGBTQ topics in their seminars, preferring to leave them to ‘people who are more focused on that topic’. In a conservative environment, this easily leads to excluding LGBTQ lives entirely, claiming methodological reasons.

In my country, Romania, the Government last year proposed to abolish ‘gender ideology’ in schools and universities, effectively erasing gender studies, queer studies, and trans people from public discourse and education. While I was pleasantly surprised to see the backlash, I could not help notice how the ‘T-word’ was excluded from most academic venues, which simply focused on queer theory as a literary approach or the right to freedom of speech. It was smart, but it also felt strange to see that discourse form so naturally, and a bit hurtful to realise that I too would tell people that the issue is with freedom of speech and sexual health, not with the Government trying to ban my very existence. I also couldn’t help thinking that the large part of the population (academia included) would not have minded if the law was passed; to them, ‘gender ideology’ is something that is not there, and the law would not have changed that. How much can the ivory tower change? I am not entirely certain.

But back to the field…Of course, there are a myriad works tackling LGBTQ issues, who are seeing infinitely vaster and more varied approaches. However, I chose my words carefully discussing my research in Japan, and even more so in Romania, though I am sure it would be considered dull and bland in the West. That there is more work to be done is a given, it wouldn’t be academia if it weren’t the case. I just feel that ‘the field’ is to begin with is a concept that is difficult to imagine. I chose my words carefully discussing my research in Japan, and even more so in Romania, though I am sure it would be considered dull and bland in the West.

Momin Rahman is Professor of Sociology, Trent University. View Momin’s E-IR article here.

Although it is LGBTQ history month, front of mind for me right now is our future, and so I am thinking about early career queer scholars, and those queers of color in particular. In part, this is because the ISA’s Queer Caucus has recently started a mentorship program that I am involved in, and partly because I try to work towards expanding equity, diversity and inclusion throughout the profession through union advocacy work and within the ISA. More specifically, the protests around the murder of George Floyd in the USA have impacted higher education, provoking reflections on how systemic racism operates in our institutions and it is good to remember that many of the IR focused queers are racialized, adding to their exclusion by the profession. I am also going to engage in shameless, intentional, promotion of queerness, beginning with an encouragement to read the contributions in the Oxford Handbook of Global LGBT and Sexual Diversity Politics, edited by yours truly with Mike Bosia and Sandy McEvoy, both stalwarts of the ISA’s LGBTQ+ caucus. Although by no means definitive, the various contributions cover both a broad regional range and key analytical issues in understanding the current state of global sexual diversity. As well as range and depth, part of what we intentionally tried to do in putting together the chapters was to encourage early career queer scholars working on queer issues. We should all be working towards equity, but I want to argue here that this is not just about statistical inclusion – a fair correlation between available pipelines and the secure workforce – but also about intellectual relevance and renewal. Sexuality studies, I suggest, is one area of research that illustrates this relationship between the politics of presence and research dynamism.

I am an outsider in IR, hailing from Sociology but, in fact, by studying sexuality, I remain something of an outsider in any of the disciplines that I engage with. In the span of my own academic career (I think I am 104 in gay years, but who’s counting?), the study of sexuality has gone from a marginal pursuit to a legitimate, if not quite yet mainstream, area of academic research and teaching. Public discussions of sexuality are now commonplace, occurring in a variety of frames ranging from rights, violence, health and education, to name but a few. This salience is, however, almost always controversial, both in the advanced capitalist societies of the global north and the global south. For example, the recent global wave of same-sex marriage legislation has not been achieved without organized resistance from social groups in either national or international contexts, often framed within a broader anti-gender ‘ideology’ politics. The current attempt to mainstream SOGIE (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Expression) as a human rights issue at the United Nations (UN) has faced similar resistance, and the same has happened within the EU and Commonwealth. Thus, sexuality should be a legitimate empirical concern within IR, but it is also more than that, it is a fundamental conceptual and methodological challenge.

At the core of the many controversies around non-normative sexualities is a battle over ‘traditional’ and ‘normal’ expectations of gender divisions and hierarchies that operate within and across national cultures, and are usually based in biological, naturalist understandings of sexual identity. This means that critical conceptualizations of sexuality remain revolutionary in that they require a thorough re-orientation of our ways of thinking; a turning away from the common sense, the taken for granted, the assumed normality of sex as a natural biological part of our human existence that anchors our sexual behaviours and identities and thus translates into an inevitable political conflicts between a ‘normal’ majority and a disruptive minority. Moreover, challenging this essentialism is only a departure point, because unpacking the political significance of sexuality is a thoroughly interdisciplinary and intersectional task. Glance over the contributions to the Oxford Handbook and you will see that the various authors deal with issues of embodiment, identities as hierarchies of norm and abnormal, irreducible intersections of gender, racialization and class. These topics alone draw upon theoretical and methodological approaches derived from women’s studies, queer studies, literary analysis, sociology and postcolonial studies. Furthermore, in the context of IR, the contributions also highlight that we need to think understand the contemporary politics of sexualities within the fundamental structures of modernity – particularly capitalism, colonialism and globalization – and how these have shaped the ways in which we produce legitimate knowledge about sexual identities and how we regulate them through social and ideological means, as well as through state action. Indeed, the empirical global divide over homosexuality cannot be explained or challenged without a nuanced and complex understanding of these factors, which demands frameworks that come from outside ‘core’ IR that is steeped in positivist epistemology. Studying sexualities is often an empirical journey through the ‘known unknowns’ and sometimes, the ‘unknown unknowns’, but not a methodological ‘unknown’ because we have ways of researching and thinking that have developed through the productive engagement of a host of disciplines.

This demand means that those pursuing sexuality studies are bringing an outsider’s perspective, but one that sees more, sees wider, and potentially brings a ‘fuller objectivity’ in doing so (Harding, 2015), productively reforming and renewing a ‘core’ discipline. We bring more to IR than IR brings to us, and that potential alone should be a reason to increase equity and diversity within the profession by understanding that ‘outsider’ issues, and those that research them, add intellectual dynamism and renewal to any discipline and curriculum.

To those early career queers and queers of color out there, feel proud of the scope and range of our research and remind yourself that you are bringing necessary renewal and challenge to a discipline through your presence. To those of us who are privileged and secure in our positions, we should recognize that we have power to ‘see’ this advantage in the outsider and to bring them inside, so that we maintain our ability for renewal and relevance.

Dr Anthony J. Langlois is an Associate Professor of International Relations at Flinders University. View Anthony’s interview with E-IR here.

I think there is more of a LGBTQ+ presence in the discipline today, but my response to the question as posed is: “who is doing the work here?” If important strides have been taken, I think they are less by “the discipline”, than by scholars who have either followed a keen (often personal) interest, and found openings within or beyond the usual round of publications and conferences, or because of frustrations and dilemmas presented by the lack of an opening, at which point people have pushed until they got through (which, needless to say, can be really tough). In either case, the doing has not been by the discipline, but by those in pursuit of space to share their work and present different, challenging, controversial ideas. I think many would attest that “the discipline” has commonly not been so interested, and the sharing (and even the creation) of the work has taken place, by necessity, elsewhere.

My own experience has been shaped by opportunities provided by scholars who have been there before me, sharing openings and possibilities, and being an example of how to contribute. I think it is critically important that this kind of collegial working together and opportunity-making be something we all do, once we get a foothold of any sort. What could be done better? My interest here would concern how we include marginalised, excluded, critical and non-conformist voices (with all of whom IR has a bad track record) – and being self-critical about this: LGBTQ+ perspectives that continue to major on homonormative goals like so-called “equal marriage” don’t cut it. There are many more pressing problems for global queers. We need to challenge the discipline, not conform to it. Viewing “the discipline” as inhospitable to radical emancipatory approaches, I don’t expect it to do much better than it currently does, given its characteristic alignments; but I do hope that those of us who find ourselves within its forms and processes can use our place of privilege to help create more spaces for this kind of work.

Jamie Hagen is a Lecturer in International Relations at Queen’s University Belfast where she is the founding co-director of the Centre for Gender in Politics. Read Jamie’s interview with E-IR here.

I am grateful for the work of feminist and queer scholars who are making more space for research about how sexuality also matters to understanding security, and for understanding IR more generally. It has made it possible for me to be hired as someone who went on the US and UK job market in 2019 explicitly focusing on queering security studies, challenging a binary approach to gender in peace and security.

I always encourage students to ask themselves, ’who is your research for?’ As someone who sees queering as directly connected to the knowledges based in queer communities, trans experiences, and survival beyond the state, I see a need to do a better job in the discipline and in the academy in general to support queer and trans people to do this research. If cis and straight people want to do this research, find ways to collaborate with and lift up those in queer and trans communities in meaningful ways such as co-authorship, collaborative research projects, and long-term slow research that can shift and adapt to meaningful outcomes. This is hard work, yet we must insist on this in light of what can be such an extractive and violent practice of knowledge production in the academy.

There is also a need for bringing an anti-racist and a decolonial approach to how queer theory is incorporated in IR. This applies to how we as a discipline think about LGBTIQ+ perspectives and research, alongside histories of sexuality. There is still a very white, Western-centric narrative of sexuality, queer theory, queer liberation in IR which does not reflect the complexity of queer history, queer organizing and the exciting visions for queer futures. I am confident being a white lesbian doing this work has made it more possible for me to stay here. It is not uncommon for me to meet queer grad students who tell me, ‘thank you so much for being out and doing this work. I have never had an openly queer instructor’. How many people have been disciplined out of IR for their focus on queer research, for being queer, for questioning the centrality of white, heterosexual, patriarchal knowledge? This is a real loss we should be sitting with when thinking through where we are now and where we want to go in the discipline.

Dean Cooper-Cunningham is a PhD Fellow at the University of Copenhagen. View Dean’s previous contributions to E-IR here.

To answer this, I want to echo some insightful words from Toni Haastrup who, when asked a similar question about race and IR, answered that “we too are the discipline of IR”. No matter how hard IR has fought to keep queer off the agenda – be it through explicit practices of disciplinary boundary-policing such as hiring, reviewing, and funding, or through silence or sheer ignorance about the politics of that ‘apolitical’, ‘personal’, ‘private’ matter of (dare I say it?) sex – it has failed. Queer IR and Global LGBT studies have made important contributions to the study of international politics, particularly with regards to systems of power and oppression. Queer people and queer scholars are ‘in’ IR. We present at and attend conferences. We produce knowledge. We publish in IR outlets. And we challenge hegemonic, institutionalised discourses about international politics and international power games. Yet, I still can’t answer the interview question (above) with a resounding ‘yes’ because that would be an outright lie; wishful thinking perhaps.

In terms of properly confronting and dealing with LGBTQ+ perspectives, research, ideas, and histories, IR hasn’t done nearly enough. Feminist IR scholars have done outstanding work showing the ways that gender affects world politics, structures all politics, is a power structure, an organising category, and that the personal is international. Gender works on all of us and constrains or authorises everything we do. Feminist work is rightly taken seriously in IR, but this has been through some arduous academic labour of so many outstanding scholars who I am intellectually indebted to. The same can’t be said of queer or LGBT work in IR. There is still a silence around the question of sex(uality) in what some call ‘mainstream IR’. The politics of (un/acceptable, ab/normal) sex is crucial to how we understand imperialism, war, mass atrocities, terrorism, global health, sovereignty, security, human rights, foreign policy, nationalism, state formation, geopolitics, and social movements. And yet, queer and LGBT work is often overlooked.

We cannot write about World War II and the Holocaust without understanding Nazi homophobia and the annihilation of so many queer people in concentration camps. How can we properly understand World War II without acknowledging its sexualised politics, that a large part of Nazi genocidal violence was sexualised, and based on purging the gays? And yet IR often does. We cannot understand the global AIDS crisis, the pandemic, without exploring the homophobia and racism underpinning the murderous inaction of world governments that left so many to die because of their ‘unnatural’ sexual behaviour, that labelled AIDS ‘divine retribution’ for gay sex. And yet IR often does. Indeed, the AIDS crisis raises one fundamental, critical question about our understanding of genocide and mass atrocities: does inaction, deliberate or not, render a government culpable? We also cannot understand Russian foreign and security policy without addressing its constitution of Europe and the West as a cesspit of queerness, as ‘gayropa’, and Russia’s civilisational Other. And yet, IR often ignores the presence of sex in international politics. By overlooking the international politics of sex, we are missing a key part of the operation of and struggles over power in international politics.As I wrote elsewhere, it is no longer acceptable to say ‘I am not asking the gender question or race or sexuality question’ because they are baked into (the study of) international politics. To echo Cynthia Enloe’s famous words, we must ask not only where are the women but where are the queers? As a word of caution: while we might be doing better at seeing, hearing, and drawing on L/G/B perspectives and histories in IR, we are failing on our engagement with trans* perspectives and histories. We must do better.