This is an excerpt from Varieties of European Subsidiarity: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Get your free download from E-International Relations.

The concept of subsidiarity has gained prominence as an organising principle for systems of multi-level governance (MLG). It captures the process by which political authority is allocated to the lowest practical level. In the European context, supranational institutions shall only take measures, if a ‘proposed action cannot be sufficiently achieved by the Member States, either at central level or at regional and local level’ (European Union 2012). Given the lack of a formal EU constitution or a centralised EU government, subsidiarity appears as an ideal method of mediating between the concerns of various actors at different levels of the European polity. As Davies (2006, 64) points out, ‘what could be more liberal than allowing the Member States to do anything that is not forbidden?’. In addition, Article 5 (3) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) places the burden of proof regarding the advantages of a centralised approach firmly on the EU (Craig 2012). Indeed, ‘the Union shall act only if and in so far as the objectives of the proposed action cannot be sufficiently achieved by the Member States’ (European Union 2012, 18).

However, there are inherent flaws within the legal capacity of subsidiarity to govern effectively. Impartiality, for example, in respecting the interests of higher and lower tiers of the EU system could only be assured if there were ’no conflict between the objectives of the various levels’ (Davies 2006, 78). As the principle impacts on core responsibilities of the state as well as of EU institutions, it will not suffice to achieve a compromise between diverging interests at different decision-making levels. To this end, it would also require the implementation of closely related legal concepts such as proportionality; or acceptance of the top-tiered, ultimate authority of the European Court of Justice. As Scharpf (2010, 230) points out: ‘European law has no language to describe and no scales to compare the normative weights of the national and European concerns at stake’. Therefore, the mediation effects and organisational merits of the legal subsidiarity concept are strongly contested. From the angle of political theory, subsidiarity is better understood as a general guiding principle to examine and design complex systems of MLG. Accordingly, this chapter does not interpret subsidiarity as a strict legal doctrine, but as an organising principle which underpins key aspects of the MLG approach. To make this point, this chapter explores the case of Export and Investment Promotion Agencies (EIPAs) and, thus, offers new insights into a key component of German and European trade policy. More specifically, it focuses on how normative subsidiarity mechanisms shape MLG in practice without following the legal prescriptions of Article 5 (3) TEU.

The complexity of governance arrangements

EIPAs are a new and understudied phenomenon from the perspective of European governance. Given the diversity of such agencies within as well as across states, the multitude of actors involved does challenge standard comparisons. Traditionally, investment promotion activities have been associated with embassies, consulates, and national delegations to trade fairs. More generally, the design and implementation of foreign economic policy was considered the responsibility of sovereign institutions. For national governments, trying to attract foreign direct investment (FDI), this meant the creation of a favourable domestic regulatory environment and direct negotiations with foreign counterparts. In turn, export promotion policy was driven by producer initiatives through chambers of commerce, trade associations and guilds, including services such as export advice, export credit insurance and marketing support. Yet, due to economic globalisation, the dividing line between state services and private sector provision has been blurred. Most states now experience the pressure to increase their global competitiveness if they want to attract foreign capital. In addition, sub-state regions seek new ways of accessing international markets and try to develop their local economies apart from national or supranational policy measures.

Within the EU, for example, each member state has – under the direction of foreign or economic ministries – created a dedicated investment promotion agency, usually in the form of a state-owned enterprise or service provider. More specifically, respective agencies can take the form of limited public liability companies, crown corporations, contracted consultancies, government departments or industry-run initiatives and associations. Frequently, this organisational set-up and the division of governance competences is the result of distinct country experiences.

To complicate things further, there has been a notable EU impact on the operation of the mixed economy. Germany, with one of the oldest and most complex systems for export and investment promotion in Europe, is a case in point. While the Federal Republic recognises subsidiarity as a key principle (Article 72 Basic Law), it differs from similar arrangements in Westminster democracies. The federal competence is subject to subsidiarity requirements as outlined in Article 72 (2) Basic Law as well as a requirement for legislative power in the specific subject matter (Taylor 2006). In fact, the 16 German state entities (Länder) insisted on the inclusion of the principle of subsidiarity in the EU treaties (Scharpf 2010). As a result of a strong domestic subsidiarity tradition, the Federal Republic operates EIPAs through a two-tiered system: one at the federal level, and one at the regional ‘Länder’ level.

Accordingly, this chapter identifies multiple levels of governance in the German and European EIPA system. Due to overlapping spheres of responsibility, the principle of subsidiarity can be observed at the core of respective EU efforts, even if it is unable to account for all EIPA activities. Instead, there is a system of shared authority across an institutionalised set of actors which works with varying degrees of unity and policy coherence as well as ‘commitment to EU norms, and power resources’ (Smith 2004, 743). In other words, the EIPA system is characterised by a loose MLG approach – or MLG type II – in the terminology advanced by Marks and Hooghe (2004). This emphasises voluntary cooperation among actors at multiple levels, sharing their authority without clear vertical hierarchies. It suggests a bottom-up approach to authority that comes with a natural delegation of authority to various working levels. However, as this chapter concludes, the recent creation of the European External Action Service (EEAS) resembles a traditional federalist top-down approach affecting EIPAs in line with Marks and Hooghe’s MLG type I approach. Regardless of MLG type, though, both system characteristics remain compatible with a general, underlying conception of subsidiarity. This recognises overlapping spheres of authority at several levels, enabling key actors to engage in vertically fluid exchanges for the sake of purposeful policy making.

EIPAS at regional and federal state level

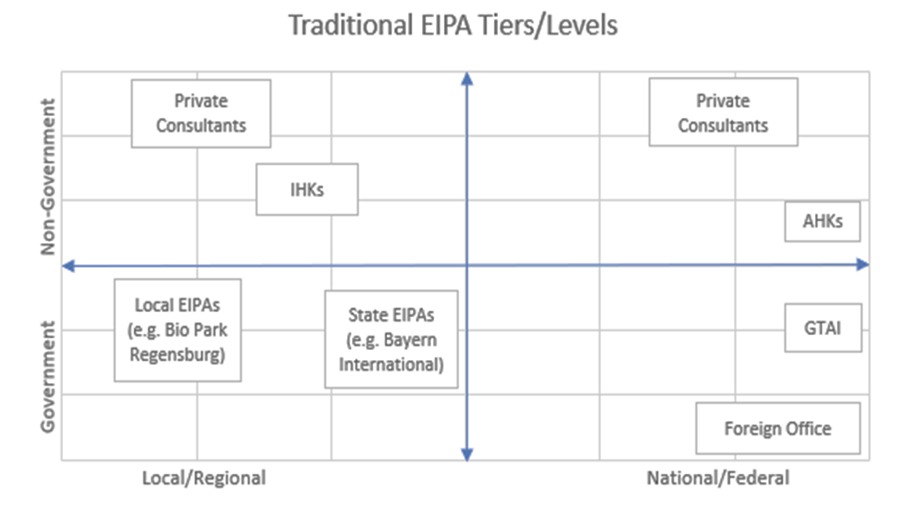

Before assessing the impact of the supranational MLG component, it is important to understand the governance relationship between EIPAs at regional and national level. Prior to the Lisbon Treaty, most European EIPAs were found in two different policy sectors (government/non-government) and at two levels of governance (local/regional – national/federal). Therefore, respective agencies could fall into one of the four categories outlined in Figure 1 for the case of Germany. The coordination system indicates a further sectoral differentiation as well as the possibility of overlapping governance arrangements.

Figure 1

Along the right quadrants of the vertical axis, there is the economic development agency of the Federal Republic (Germany Trade and Invest, GTAI), as well as the German system of Chambers of Commerce Abroad (Auslandshandelskammern, AHKs). Both organisational forms promote investment flows into the country, while simultaneously representing German export interests abroad. At the local or regional level, EIPAs follow more closely the principle of subsidiarity through an exclusive focus on sub-state promotion efforts. This includes EIPAs of the German Länder such as Bayern International, Baden-Württemberg International, and Berlin Partner, or region-specific Chambers of Commerce (Industrie- und Handelskammern, IHKs). Frequently, these too operate with a dual task division of inward FDI promotion and external trade support. In the case of Bavaria, for instance, the relevant state ministry operates two separate companies, one dealing with FDI (Invest in Bavaria), and one dealing with export promotion and foreign market development (Bayern International). In the case of neighbouring Baden Württemberg, by contrast, the task division is achieved through two different departments within a single official agency (Baden-Württemberg International, BW-I).

Along the horizontal axis, the traditional relationship between local and national EIPAs does not follow a centralised or hierarchical pattern. The actors at national or federal level have no legal authority over their counterparts at local or regional level. Given the federal political system, the local and regional EIPAs interact with their respective state governments (Landesregierungen), and do not maintain institutional ties with the federal government (Bundesregierung) or centralised private business initiatives. In fact, the local and regional EIPAs are owned and operated by state governments, whereas local Chambers of Commerce (IHKs) are private non-profit associations, joined up in a federal network with the Association of German Industry and Trade Chambers (Deutscher Industrie und Handelskammertag, DIHK) as their umbrella organisation. Again, the latter has no control over the activities of individual IHKs but represents their views for lobbying purposes at national level.

Some regional EIPAs follow a hybrid commercial model with several shareholders coming from the public and semi-public arena. BW-I, for example, is financed by the Land, its state bank, and the industry association of Baden-Württemberg, as well as an umbrella organisation of local chambers of trade and commerce. It is also worth noting that neither of the two identified levels has a centralised planning or coordinating committee to streamline activities within different segments of the system. Thus, subsidiarity is not an official component of German foreign economic policy and, instead, finds its recognition in the informal practices of organisational actors adhering to the related principle of federal comity.

The German system in practice

At federal level, GTAI and AHKs work closely with local EIPA actors and involve them in their own initiatives. Local EIPAs are feeder organisations providing federal agencies with export-ready contracts, new clients and emerging opportunities through direct access to valuable information from the local business community. Moreover, for the externally operating AHKs, local agencies in Germany are potential customers and a source of income, providing funding for trade delegations, marketing events or contracts of representation. Usually, this collaboration is based on personal relationships that are fostered and maintained informally on behalf of federal agencies. Therefore, EIPAs in the German system are free to cooperate with each other across different levels as this is perceived to be in their own economic interest.

In practice, local promotion agencies have become tenants in the foreign offices of their federal counterparts, outsourcing the planning of trade delegations, making budgetary contributions or co-financing members of staff to represent their specific interests internationally. For example, already since the 1990s the state of Bavaria has operated its own network of 20 global business representations with major support coming from the staff of German Chambers of Commerce Abroad (AHKs) (Bayerisches Staatsministerium 2017). In this set-up, subsidiarity arrangements allow local regions to run international promotion networks independently of federal interference. The MLG approach is a useful tool in analysing the related cooperation and coordination efforts between different groups of actors.

The federal government endorses this system despite rare cases where centrally funded EIPAs have concentrated excessively on the collaborative relationship with a single local provider. Under such circumstances, it will issue a reminder to the federal agency about the obligation to serve the economic development of the whole country rather than handing competitive advantages to individual regions. Due to the lack of an overarching organisational structure, the system relies on shared economic concerns as part of Germany’s national interest. Thus, the country-specific governance structure follows neo-functionalist understandings as embedded in the MLG type II concept. Here, authority is not exercised around pre-existing vertical hierarchies but evolves with specific problem constellations (Hooghe and Marks 2003). This has the advantage to allow for competitive processes among different sets of actors in overlapping areas of jurisdiction. True to the spirit of subsidiarity, individual levels of governance must prove their ability to outperform others in their capacity to realise new business opportunities. Potentially, this competition can also be used as a deliberate policy instrument to increase the quality or efficiency of service delivery (Benz 2007). Overall, the relative autonomy of EIPAs in the German system has led to a high degree of specialisation and resource maximisation in external promotion efforts. Similarly, in terms of inward investment acquisition, the GTAI as the key federal actor with worldwide presence is well-positioned to identify local and regional partner organisations for foreign customers. While the EIPAs at higher and lower levels can operate independently in this market segment, they are likely to cooperate with each other for the sake of cost effectiveness.

Consequently, the effectiveness of the co-ordination process across several levels depends largely on communication flows in interpersonal networks and the readiness of key actors to engage in voluntary exchanges. If personal relationships break down, or individual representatives have not sufficiently internalised subsidiarity norms, significant financial burdens can follow in terms of duplicate institutional structures or identical service provision. Together with inefficient resource allocation, this may add to a degree of confusion among domestic exporters and external investors in the day-to-day running of the system. What is more, the complexity of the coordination system makes EIPAs particularly sensitive to changes in the external environment. The absence of clear delineations of competences between levels of governance complicates public-private interactions and requires political decision-making to respond adequately to new funding streams and business opportunities.

Take, in this context, the rapid organisational change that occurred in the regional promotion system of the state of Lower Saxony (Niedersachsen). In 2009, the Land brought its dedicated investment promotion agency into public-private ownership, now constituted as a limited liability company (NGlobal GmbH) and equipped with an international network for export promotion. The shares of the reformed entity were held by the state of Lower Saxony, a regional trade fair organiser (Deutsche Messe), a local state bank (NordLB), local chambers of commerce, as well as a semi-public academy for management training (Deutsche Management Akademie). Already two years later, the official state component dealing with investment acquisition was relocated to another semi-private company, supposedly to serve the specific purpose of business innovation (Innovationszentrum Niedersachsen GmbH) (Niedersächsisches Ministerium 2013a). Finally, in 2013, NGlobal was dismantled to give way for a new government department in the Ministry for Economic Affairs, Labour and Transport, re-uniting investment acquisition, export promotion as well as the related delegation and networking activities in a single public entity. In the words of the responsible Minister, Olaf Lies (Niedersächsisches Ministerium 2013b; author’s translation):

After analysing the existing export promotion system, the criticism of the business community, and the requests of the ministerial bureaucracy, I have decided to re-integrate foreign trade development into the Ministry for Economic Affairs, Labour and Transport.

The observed tension between public and private provision of promotion activities has a historical legacy. Not only was the creation of Chambers of Commerce Abroad perceived as an unnecessary duplication of services, it also challenged the sovereign monopoly of the state to conduct international trade policy. Parliamentary debates going back as far as Reichstag sessions in the period from 1899 to 1901 indicate the critical attitude held by the Foreign Office (Auswärtiges Amt) in response to the opening of the first German Chamber of Commerce in Brussels (Reichstagsprotokolle 1903). More than a century later, the non-governmental sector represented by the domestic IHK system and the externally located AHKs is considered an important element of official governmental policy and formally recognised as the third pillar of external trade promotion. Currently, the respective network spans 139 international offices (with more than 1500 members of staff) and with up to 20 per cent of their budgets covered by direct federal grants. By contrast, the private non-associational sector populated with consultancies such as Price Waterhouse Coopers (PwC) or Ernst and Young (EY) plays a much smaller role. In recent years, their activities have concentrated on the winning of government contracts to conduct advertising campaigns, to organise trade delegations and to attract inward FDI.

The impact of the EEAS

From the German perspective, the practical EU attempts to implement the principle of subsidiarity are anything but clear cut, especially if responsibilities are supposed to be allocated to the lowest possible level. Comparable to other policy areas addressed in this book, the empowerment of actors at the EU member state level has not been a prime target. Recurrent EU efforts in the field of export and investment promotion have clashed with organically grown national promotion systems, while attempting to supersede their mandate by the formation of genuine European actor capacity. Hence, it would be misleading to connect subsidiarity with a bottom-up approach. Instead, the insertion of an additional top- layer serves to by-pass national governments while directly engaging with local or regional agencies. With the ratification of the Lisbon Treaty, the ambition of a pan-European approach has become much more obvious.

In particular, the creation of the EEAS has impacted external trade promotion and the EIPAs of the member states. Following Council Decision 2010/427/EU, the diplomatic service has seen a dramatic expansion to 139 internationally operating offices. With a budget exceeding 600 million euros, a workforce of 4237 people, and more than half of those active in EU delegations abroad, actor capacity in European foreign policy cannot be denied (EEAS 2017). In analogy to the turf battles between the EEAS and national foreign services, similar skirmishes are expected with the actors of domestic promotion systems (Adler-Nissen 2014). The EU already holds exclusive competences in external trade relations and negotiates on behalf of the member states through the Directorate General for Trade of the Commission (DG Trade). In addition, the EEAS (2019) interprets the portfolio of its delegations rather broadly in so far as they are

responsible for all policy areas of the relationship between the EU and the host country – be they political, economic, trade or on human rights and in building relationships with partners in civil society.

Unfortunately, the 2013 reform review of the EEAS neither mentioned subsidiarity concerns nor suggested alternative forms of sharing authority in a strengthened system of European governance. This, by the way, is in stark contrast to the vision originally outlined for lower-level actors in the 2009 White Paper on Multilevel Governance (Committee of the Regions 2009). In fact, the EEAS (2013, 18) seems to harbour even more far-reaching ambitions by addressing

residual competence issues to ensure that EEAS and EU delegations are the single channel for EU external relations issues, including in areas of mixed competence and in multilateral fora.

Therefore, de facto, the EU has already established a third level of authority, which ultimately acts within the same sphere as traditional trading states. This poses a long-term challenge to the policy instruments in the hands of national export promotion agencies as well as the lobbying activities of embassies and consulates.

Towards a European EIPA system?

Of course, an additional sphere of EU responsibility does not automatically undermine all subsidiarity concerns as expressed in Article 5 (3) TEU. It is an empirical question how the practical interaction with the member states impinges on domestic action capacity in trade matters. In this respect, a major point of contestation has been the role of EEAS delegations in initiating and co-funding European Chambers of Commerce (ECC) in third countries. In contrast to German AHKs, these reveal no standardised structure in their formal set-up or exhibit regulatory constraints in their external promotion activities. Accordingly, they are recognised as an emerging challenge to the dominant business model of national EIPAs. If their numbers increase – while offering comparable services within a larger network – private companies at local, regional and national levels could be easily persuaded to switch providers.

On the one hand, representatives of the German EIPA system appreciate the positive advocacy role of EEAS delegations in multilateral trade relations. From this angle, it makes sense for larger member states to actively cooperate and shape new pan-European initiatives. On the other hand, this entails the risk that over time the EEAS and ECC services will be in direct competition with national provisions once these have gained access to EU-wide funding opportunities. Indeed, the recent EU efforts point in the direction of a federalist type I approach to MLG. Although the actors at lower levels are not centrally controlled within a strictly hierarchical relationship, the top-layer tries to delegate authority downwards without allowing for a more fluid, interactive exchange. The first step towards a European EIPA system challenges the raison d’être of established national organisations, even if it is welcomed by some of the smaller member states hoping for a better resource flow to their export and investment projects.

Paradoxically, the traditional EU policy strategy in this sector, originating in the pre-Lisbon period, was closer to MLG type II. Due to an emphasis on common problem-solving and resource maximisation rather than hierarchical ordering, it better incorporated the subsidiarity considerations of Article 5 (3) TEU. In fact, the EU continues to support national export promotion efforts through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), which leaves actual implementation in the hands of downstream actors.

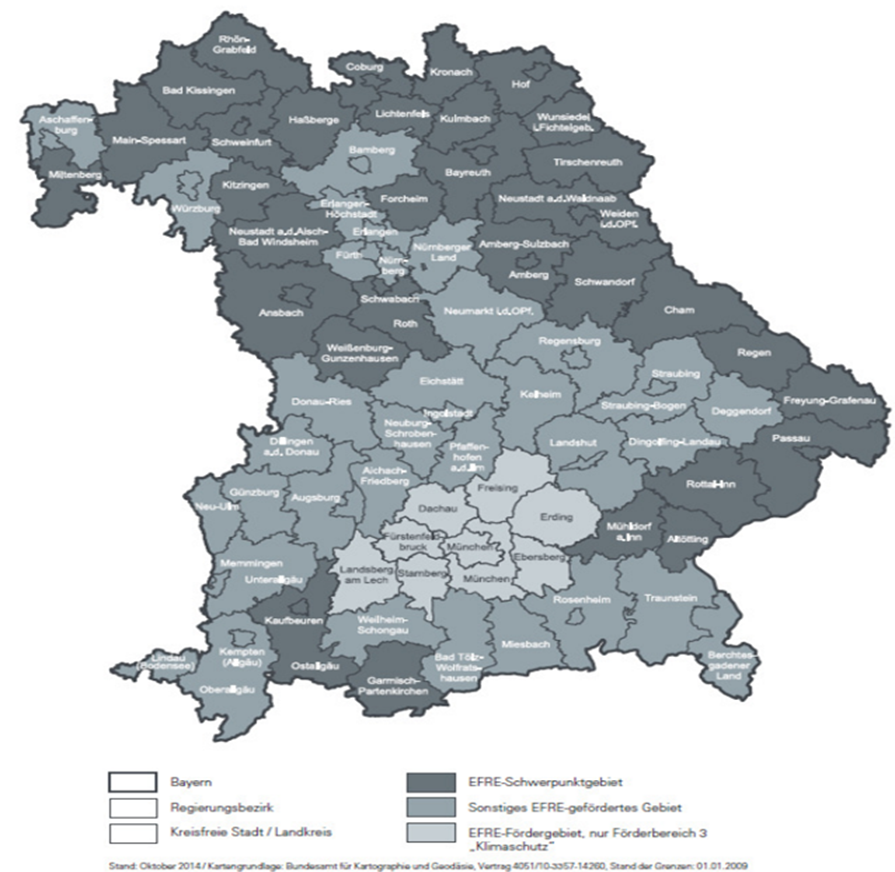

Take, for example, the ongoing Bavarian ‘Go International’ project for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The participating businesses are entitled for reimbursements of up to half of their export promotion expenses within an individual limit of 20,000 euros over a three-year period. The overall organisation rests with regional chambers of commerce and trade, who administer the joint funding from the ERDF and the Bavarian Ministry for Economic Affairs, Media, Energy and Technology. Importantly, the precise co-funding arrangements depend on the geographic location and industrial sector of the participating SMEs. For this purpose, as Figure 2 shows, the ERDF identifies priority areas and funding opportunities targeted at specific government districts and city regions in Bavaria (BIHK Service 2017). Despite their complexity, such funding streams are more suitable for the classic MLG type II environment of the German case. The established EIPAs can still tap into EU resources, yet without sacrificing their operational independence.

Figure 2: ERDF priority areas in Bavaria, 2014–2020. Source: BIHK Service (2017, 4).

Similarly, the role of the European Commission in providing grants or co-funding arrangements for EU external promotion projects aligns more closely with subsidiarity demands. Consider, in this context, the joint EU-Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Invest project, running for three years from 2012 to 2015. It did join up traditional AHK actors in the form of the German Emirati Joint Council for Industry and Commerce and the German-Saudi Liaison Office for Economic Affairs with relatively new arrangements such as the GCC Federation of Chambers and Eurochambres, an ECC umbrella organisation. The partnership, furthermore, intended to engage all European EIPAs in the Gulf region through the conduct of conferences, workshops and study programmes.

Essentially, the Commission does not implement policy measures on the ground but calls for proposals from the EIPAs of the member states. The project offer came with an EU co-funding promise of 60 per cent, if other partners contributed through their workforce to the remaining costs. Different to the Bavarian ERDF project, the Brussels institution insisted here on an inclusive approach. For EU-GCC Invest, the explicit aim was to involve as many member state EIPAs as possible in programme activities, also to disseminate widely the available information on European investment promotion systems. Moreover, the participation of national providers from Europe was entirely voluntary; the UK’s former Trade and Invest department (UKTI), for example, preferred to chart its own path in the Gulf region. In fact, even the participating German AHK offices remained autonomous and, ultimately, in charge of the implementation process through their own members of staff. In short, the EU programme did not attempt to establish competing governance structures and, instead, had the objective to foster those already in place. In sum, the examples presented in this section show that MLG type I and II coexist in the complex space of European export and investment promotion. However, if subsidiarity is taken seriously, it champions a traditional bottom-up use of policy tools in support of local, regional and national agencies.

Conclusion

The MLG approach is particularly useful to understand the sharing of authority across different levels of the European polity. In the case of German export and investment promotion policy, bottom-up and top-down processes coexist. For the actors in the observed EIPA systems, informal conceptions of subsidiarity matter when setting out the general direction of their organisational relationships. Rather than suggesting mere decentralisation to the lowest working level, the policy area analysed here suggests sharing arrangements by autonomous actors operating at different organisational levels and with various sectoral divisions. Instead of centrally enforced governance, EIPA efforts are dominated by voluntary, market-driven cooperation. Under such conditions, the concept of subsidiarity works as a compass steering the fluid transfer of authority in promotion systems with strong vertical dynamics.

Traditionally, a similar relationship existed in the EU dimension when using Commission and ERDF funding. At first sight, therefore, the expansion of EEAS delegations and creation of ECCs constitutes a significant challenge to the EIPA structures of the member states, and especially to those of the Federal Republic. Yet, given the fact that the new ‘top’ EU tier neither bans nor supersedes the promotion activities of national EIPAs, the relevance of the subsidiarity principle remains intact in the European dimension of foreign economic policy. Regardless of whether the adaptation to changing trade relations occurs at home or abroad, the distinction between two MLG types, advanced in this chapter, is vital to understand the normative implications of subsidiarity.

References

Adler-Nissen, R. (2014). ‘Symbolic Power in European Diplomacy: The Struggle between National Foreign Services and the EU’s External Action Service’. Review of International Studies 40(4): 657–81.

Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Wirtschaft und Medien, Energie und Technologie (2017). Bayerische Repräsentanzen im Ausland – Bavarian Representative Offices Worldwide. Available at: https://www.stmwi.bayern.de/fileadmin/user_upload/stmwi/Publikationen/2017/20170117-Bay_Repraesentanzen_im_Ausland_TB_Januar_2017.pdf

Benz, A. (2007). ‘Inter-Regional Competition in Co-operative Federalism: New Modes of Multi-level Governance in Germany’. Regional and Federal Studies 17(4): 421–36.

BIHK Service (2017). Förderbestimmungen über das Förderprojekt ‘Export Bavaria 3.0 – Go International’. Available at: http://www.auwi-bayern.de/awp/foren/go-international/anhaenge/foerderbestimmungen-go-international.pdf

Committee of the Regions of the EU (2009). The Committee of the Regions’ White Paper on Multilevel Governance, CdR 89/2009 fin. Available at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/afco/dv/livre-blanc_/livre-blanc_en.pdf

Craig, P. (2012). ‘Subsidiarity : A Political and Legal Analysis’. Journal of Common Market Studies 50(1): 72–87.

Davies, G. (2006). ‘Subsidiarity: The Wrong Idea, In The Wrong Place, At The Wrong Time’. Common Market Law Review 43: 63–84.

European External Action Service (2013). EEAS Review. Available at: http://collections.internetmemory.org/haeu/20160313172652/http://eeas.europa.eu/library/publications/2013/3/2013_eeas_review_en.pdf

European External Action Service (2017). Annual Activity Report 2016. Available at: https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/aar2016_final_final.pdf

European External Action Service (2019). About the European External Action Service (EEAS). Available at: https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/82/about-european-external-action-service-eeas_en

European Union (2012). ‘Consolidated Version of the Treaty on European Union’. Official Journal of the European Union C 326/13, 26 October. 13–46. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:2bf140bf-a3f8-4ab2-b506-fd71826e6da6.0023.02/DOC_1&format=PDF

Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. (2003). ‘Unraveling the Central State , but How ? Types of Multi-Level Governance’. American Political Science Review 97(2): 233–43.

Marks, G. and Hooghe, L. (2004). ‘Contrasting Visions of Multi-level Governance’. In Bache, I. and M. Flinders (eds) Multi-level Governance, 15–30. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Niedersächsisches Ministerium für Wirtschaft, Arbeit und Verkehr (2013a). Antwort vom Minister für Wirtschaft, Arbeit und Verkehr Olaf Lies auf die mündliche Anfrage der Abgeordneten Jörg Bode, Gabriela König und Christian Dürr (FDP). Sitzung des Niedersächsischen Landtages am 01.11.2013 – Top 26. Available at: http://www.mw.niedersachsen.de/aktuelles/presseinformationen/unternehmensansiedlung-119422.html

Niedersächsisches Ministerium für Wirtschaft, Arbeit und Verkehr (2013b). Außenwirtschaftsförderung wird neu aufgestellt und Chefsache. Available at: http://www.mw.niedersachsen.de/aktuelles/presseinformationen/auenwirtschaftsfoerderung-wird-neu-aufgestellt-und-chefsache-118175.html

Reichstagsprotokolle (1903). Stenographische Berichte über die Verhandlungen des Reichstags. Berlin: Norddeutsche Buchdruckerei.

Scharpf, F.W. (2010). ‘The Double Asymmetry of European Integration Or : Why the EU Cannot Be a Social Market Economy’. Socio-Economic Review 8: 211–50.

Smith, M.E. (2004). ‘Toward a Theory of EU Foreign Policy Making: Multi-level Governance, Domestic Politics, and National Adaptation to Europe’s Common Foreign and Security Policy’. Journal of European Public Policy 11(4): 740–58.

Taylor, G. (2006). ‘Germany: The Subsidiarity Principle’. Institutional Journal of Constitutional Law 4(1): 115–30.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Subsidiarity and Fiscal Federalism in Canada

- Subsidiarity: A Principle for Global Trade Governance?

- Introducing Varieties of European Subsidiarity

- The Political Philosophy of European Subsidiarity

- Subsidiarity and the History of European Integration

- European Foreign Policy and the Realities of Subsidiarity