Covid-19 impacted diplomacy in an unprecedented way. The wheels of international diplomacy came to a grinding halt. Foreign ministries, Embassies and multilateral institutions all shut their doors. The UN Security Council Chamber was abandoned; the Palais des Nations in Geneva grew silent while NATO headquarters lay dormant. As physical diplomacy was suspended, diplomat’s turned to digital technologies hoping to overcome restrictions and lockdowns. Some Embassies used WhatsApp groups to coordinate consular aid. Other diplomats turned to social media to interact with citizens stranded in remote locations. Yet above, diplomats embraced video conferencing. Indeed, the use of Zoom-like technologies became so ubiquitous that video conferencing shaped the aesthetics of leadership during the pandemic. Images of leaders partaking in conference calls, as shown in Figure 1, were used to signal effective crisis management.

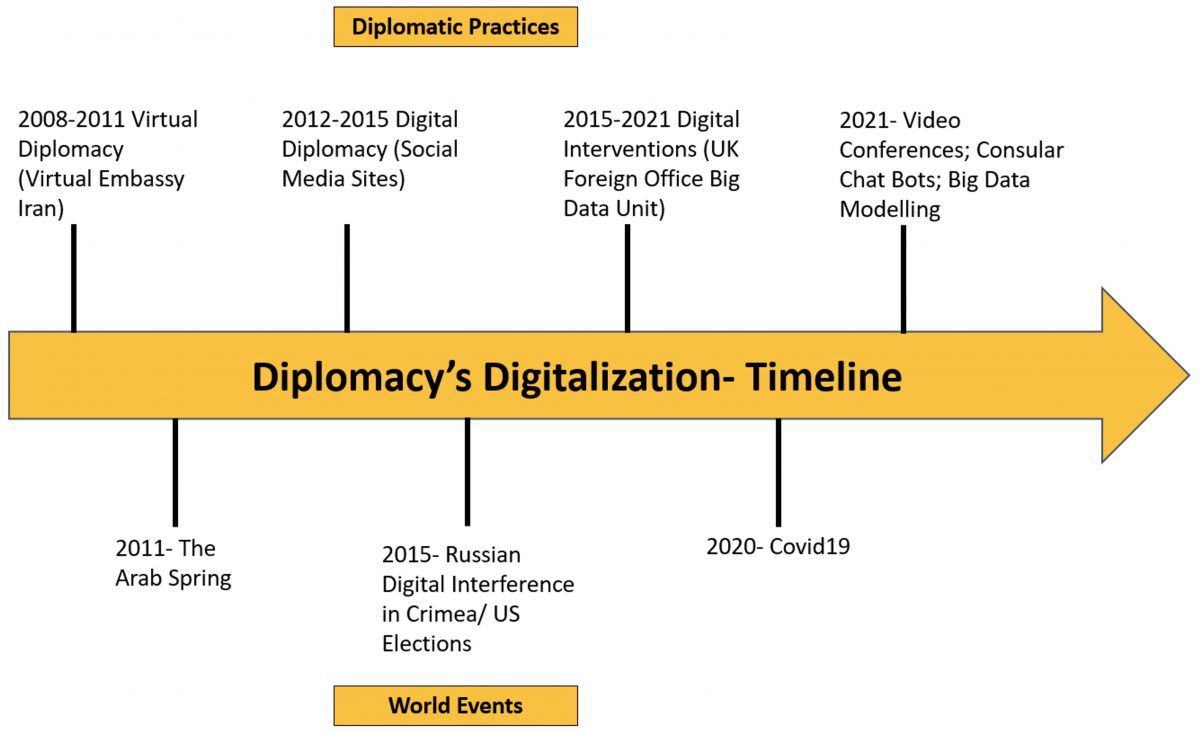

The question that this article asks is what digital technologies, leveraged during Covid-19, will remain integral to diplomacy once the pandemic has passed? This is an important question given that the wheels of diplomacy are already back in motion. In March 2021, foreign ministers physically attended meetings at NATO headquarters in Brussels and signed strategic agreements in Tehran. To answer this question one must first examine the trajectory of diplomacy’s digitalization. Practitioners believe that diplomacy’s digitalization has advanced in a linear fashion. Up to 2012, diplomats used virtual Embassies to overcome the limitations of offline diplomacy, as evident in the launching of America’s virtual Embassy to Iran meant to overcome lack of bi-lateral ties. Next, diplomats turned to social media where they sought to interact with distant diasporas or shape the worldviews of foreign publics. This was followed by diplomat’s mastering of algorithms and the establishment of digital diplomacy departments. Finally, MFAs launched their own smartphone applications.

Yet, a closer inspection reveals that the digitalization of diplomacy has been consistently shaped by offline events. The Arab spring was the first offline event to alter the trajectory of diplomacy’s digitalization. The limited use of social media by Arab Spring protestors saw a shift from virtual diplomacy, marked by virtual Embassies, to digital diplomacy, marked by diplomats’ mass utilization of social media sites. MFAs believed that through social media they could interact with foreign populations, shape their worldviews and advance foreign policy goals. Yet digital diplomacy also rested on ‘listening’, or monitoring online conversations to anticipate the next wave of disruptive revolutions.

The trajectory of digitalization was altered yet again following Russian digital disinformation campaigns during the 2014 Crimea Crisis and the 2016 US elections. Diplomats came to regard social media as tools for foreign interference. Subsequently, the British Foreign Office established a big data unit tasked with monitoring and disabling fake social media accounts. To combat disinformation and hate speech online, the Israeli MFA created an algorithmic unit where programmers wrote algorithms that interfaced with social media platforms and automatically removed hateful content.

Covid-19 will likely alter the trajectory of diplomacy’s digitalization once more given that the world may soon face a similar crisis be it due to environmental degradation or the ease with which viruses can spread in a networked world. As Hannah Ardent wrote, everything that has a precedent is destined to happen again. Keeping Ardent’s warning in mind, it is fair to assume that three digital technologies will remain integral to diplomacy following Covid-19. These technologies will help diplomats overcome the challenges posed by Covid-19 – the absence of physical diplomacy and the need to mount global, consular operations.

The first technology to outlive Covid-19 is video conferencing. Diplomats have developed an affinity for conferencing which helps save time and resources. This is especially true of multilateral hubs where diplomats spend hours travelling from one institution to the next. Ambassadors to the UN in Geneva, for instance, begin the day at the World Trade Organization, then travel to the International Labor Organization before briefing the World Health Organization. Moreover, video conferencing enables MFAs to continuously train their diplomats. During Covid-19, the Swedish, Danish, Portuguese and Israeli MFAs used video conferencing to hold professional seminars and workshops. Multilateral institutions and MFAs may soon develop their own video conferencing platforms that could be used in the next global crisis thus ensuring that diplomacy continues to function, even in the absence of physical contact.

The second technology to outlast Covid-19 is chat bots. Bots are automated software meant to mimic human behavior. During the pandemic, the Lithuanian MFA designed its own consular chat bot. Given the MFA’s limited size and resources, the Bot was designed to answer basic consular questions, ranging from emergency charted flights to listing travel warnings. When the bot encountered questions it could not answer, citizens were referred to diplomats. Future pandemics are also likely to be characterized by the need to mount global consular rescue efforts. Sophisticated chat bots can reduce the strain on consular departments while providing crucial information to citizens.

The third technology is big data modelling. Throughout the pandemic, Israel operated a joint ‘war room’ bringing together diplomats, health workers, epidemiologists and computer scientists. Their goal was to track the likely progression of Covid-19 and focus efforts on areas that may encounter an outbreak. Such modelling may serve as the basis for future responses to global consular challenges as diplomats may extrapolate the possible trajectory of a pandemic. For instance, models can show that an outbreak in Germany will soon lead to an outbreak in Italy. Diplomats can then focus their efforts on evacuating citizens from Italy, while those stranded in Japan become a second priority. Digital collaborations between MFAs and ministries of health may improve diplomats’ ability to meet consular needs during a global crisis.

Covid-19’s digital legacy will thus be centered on distance. Video conferencing will be used to overcome social distancing while big data modelling will narrow the distance between diplomats and stranded citizens thanks to effective prioritization. Thus, an offline event will once again alter diplomacy’s digitalization leading diplomats to embrace new digital technologies and new working routines.

Figure 1: The Aesthetics of Leadership During Covid-19

Figure 2: How Offline Events Shape Diplomacy’s Digitalization

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The European Union’s Digital Strategy and COVID-19

- Can Populism Survive COVID-19?

- Nigeria’s Soft Power in the Face of COVID-19

- The United Nations’ COVID-19 Dilemmas: Towards a Budgetary Crisis?

- Opinion – Multilateralism as Panacea for COVID-19

- Opinion – Revisiting Paradiplomacy in the Context of COVID-19