Hip hop places a particular emphasis on marginalised groups and ‘keeping it real’- a popular phrase in the hip hop community reflecting the importance of behaving and sharing messages consistent with ones’ personal experience.[1] This, in addition to its spectacular spread globally and malleability in being able to take on localised meanings and sounds, makes it difficult to square with existing understandings of music in IR which conceptualise the role of sound in terms of top-down forces and domination by institutional, national and commercial interests. At a wider level, studies of IR tend to neglect the role of individual agency in favour of explanations resting on global power relations and structural forces.[2] As such, a qualitative study of hip hop’s emergence and spread around the globe, tracing particular musical motifs and artists’ careers is advanced to assess to what extent the genre serves to challenge these existing understandings in IR. Thus, hip hop is positioned as possible study material in IR to explore the role of lived experience and individual agency beneath the visible flows of power that are already so well recognised in the discipline- in effect, this discussion balances the importance of ‘keeping it real’ against ‘keeping it realist’ in studies of IR.

Theoretical Framework

“Representation is always an act of power” according to Robert Bleiker’s ‘The Aesthetic Turn in International Political Theory’[3], describing a shift away from mimetic approaches to the discipline which seek to “represent politics as realistically and authentically as possible”.[4] Instead, aesthetic studies of IR recognise the inevitable distance between the represented and their representation and thus take representations themselves as a fundamental unit of analysis, generating a “more diverse but also more direct encounter with the political”.[5] This approach aligns itself with what Eric Selbin & Meghana Nayak describe as the ‘centring’ of IR on voices from the global north/west, “[privileging] certain political projects” and “completely [missing] multiple ways of understanding and living in the world”.[6] For Selbin & Nayak, decentring IR is not simply about “inserting case studies from around the world”[7] and an aesthetic approach can be seen to be particularly useful here, mobilising alternative modes of study that allow us to confront “the way we talk about, share and experience these narratives”.[8]

At a broader level, these approaches suggest that dominant studies of IR, such as realism’s emphasis on power dynamics and international structure in explaining international reality, miss something fundamental in the lived reality for groups around the globe. For instance, Selbin & Nayak describe how the African oral historical tradition has been neglected in studies of IR in favour of traditionally European modes of information[9] and, as such, Bleiker advises that we “forget IR theory” altogether in order to “escape the vicious circle by which these social practices serve to legitimise and objectivise the very discourses that have given rise to them”.[10] Following these warnings, this research paper positions itself alongside aesthetic approaches to IR in order to highlight the value and causal importance of lived international reality beneath the dominant and well-recognised flows of power. Inadvertently, the case of hip hop has a great deal of symbolic relevance to Selbin & Nayak’s call to recognise other modes of information in IR in order to alleviate its centring on Europe and the West, not only utilising oral methods of sharing knowledge but directly evolving out of these African historical traditions.[11]

Methodology

In particular, Jessica Gienow-Hecht’s chapter ‘Nation Branding’ talks of the “power in being respected and listened to”.[12] This study follows the qualitative biographical approach utilised in Frederic Ramel and Cecil Prevost-Thomas’ collection of articles ‘International Relations, Music and Diplomacy’which perceives an “acoustic turn in IR” [13], as well as in Naeem Inayatullah’s “Gigging on the World Stage: Bossa Nova & Afrobeat After De-Reification’.[14] In the cases of the Brazilian bossa nova and Fela Kuti’s innovation in Afrobeat, Inayatullah traces the movements of musical motifs and artists’ careers in their international context to glean insights into how music embroils itself in and relates to wider power structures. This methodology will be mobilised here in the case of hip hop, tracing the genre’s emergence and spread across the globe to provide a functional model of the role of music in IR.

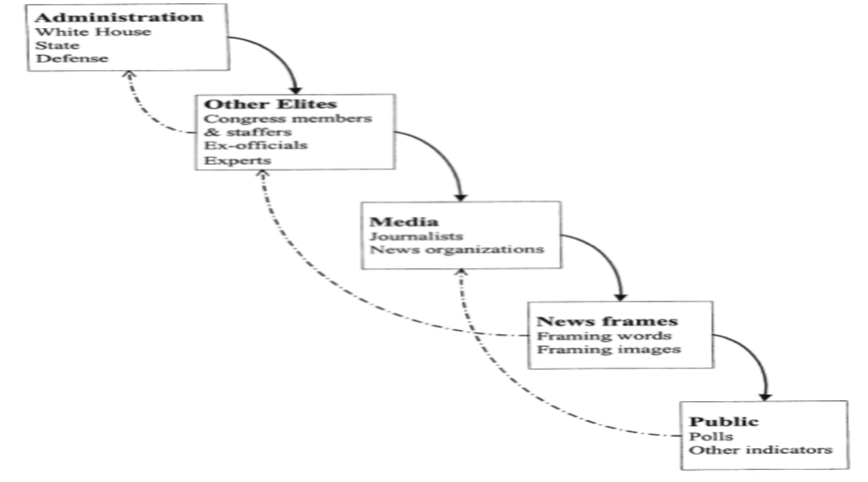

In doing so, this paper involves itself in a series of dynamics that prove a clean and simple understanding of music impossible- representations and culture inhabit a space that is complicated by debates regarding the dialectics of subjectivity[15] as well as our understanding of how information spreads through society. With regard to these questions, cultural studies’ concepts of ‘non-reductive materialism’[16] and ‘cultural hybridity’[17] are particularly useful in illustrating the non-deterministic yet still potent role of cultural and representational ideas in society and is mobilised as a rubric for understanding the simultaneous top-down and bottom-up flows in the creation, spread and role of music in IR. Theories of media can also be seen to have particular relevance to these debates- looking at how information flows through and affects decision-making within society. Between James Hoge’s notion of “media pervasiveness”[18] and the CNN effect[19] which emphasise media’s radical role in affecting policy decisions and Noam Chomsky’s propaganda model focussing on agenda-setting functions of society’s elite on media establishments[20], Robert Entman’s “cascade model” illustrates how these dynamics act and affect each other simultaneously.[21] A similar model will be drawn in the case of music in its international context, recognising how individual agency relates to wider agendas and power relations in the emergence and spread of particular sounds.

As a whole, this study looks to advance hip hop as a key case study in highlighting the value and radical importance of representation and lived experience in IR, illustrating this on a model that integrates both top-down and bottom-up flows in music’s functions and engaging with established views of music’s role in IR as well as understandings of culture and representation in the context of globalisation. In particular, hip hop will be discussed in the context of (in order): the emergence and spread of the genre itself, arising out of a series of cross-cultural exchanges; the Chinese hip hop scene, in which its existence as a radical element in society is especially apparent; the Middle East, where hip hop artists played an influential role in the Arab Spring; the wider South Korean music culture, in which government bodies frequently deploy the commercial power of music to serve national interests; and, finally, in the wider context of music over history, at which point it will be considered to what extent these qualities of hip hop are inherent in the medium itself. Solomon PM’s database ‘Hip Hop Around the World’[22], compiling hip hop songs from every country on Earth, will be used as a backbone of this study whilst also taking a closer look at the biographical trivia of particular regions and hip hop cultures to explore to what extent hip hop is a revolution in the ways ideas and experiences are expressed on the international stage.

Literature Review

Ramel and Prevost-Thomas’ collection of articles ‘International Relations, Music and Diplomacy’ emphasises how “throughout history… musicians have served as national representatives”[23], drawing on case studies such as Rebekah Ahrendt’s study of the ‘Diplomatic Viol’[24] and or Gienow-Hecht’s broader look at these dynamics in ‘Of Dreams and Desire: Diplomacy and Musical Nation Branding since the Early Modern Period’.[25] Gienow-Hecht largely follows Bleiker’s aesthetic approach to IR, positioning nation branding in the context of the “power in being respected and listened to”, however, arguing that “nations derive their existence from external self-representation”, ultimately understands music in IR in terms of projections of soft power for the nation it was produced in.[26] These views can broadly be understood to take a top-down approach to music in focussing on how musicians and sounds are deployed for national interests. Ronald Radano & Tejumola Olaniyan’s ‘Audible Empire: Music, Global Politics, Critique’ takes a similar line, conceptualising “empire as an audible formation”[27] which “draws the listener into a vast network of language, supra-linguistic sensory fields, regimes of knowledge and new modes of subjectivity”.[28] As such, they maintain a cautious view of the modern “cultural industry” in the age of globalisation, echoing Theodore Adorno’s conclusion that music today is now defined by “banality and repetition”[29] and more broadly views of globalisation as a homogenising force, most prominently expressed in what Ulf Hannerz calls the “murderous threat of cultural imperialism”[30]. Finally, Kendra Salois’ specific studies into hip hop and its role in “US cultural diplomacy” also focus on these top-down dynamics, arguing that, despite their best efforts to maintain the validity of their art, hip hop artists part of the US “American Music Abroad” program find themselves inadvertently advocating central agendas such as neoliberal discourse.[31] Nonetheless, critically she does not find these top-down flows to be completely determinant, noting that it is “impossible to differentiate the dominating effects of institutional policies from the desires and politics of individual actors”.[32] Meanwhile, Rebecca Blanchard’s ‘The Social Significance of Rap & Hip Hop’ expresses an intermediary position, both recognising “rap’s potential for political advocacy”[33] as well as the constraining effect that commercial and political forces have had on artists’ expression- as various radio stations were gradually bought up by larger corporations “controlled mainly by members of the white upper class”, rappers were “pressured to take on the limited roles that have proven profitable for young, African-American male artists—that of the ‘pimp’, the ‘gansta’ and the ‘playa’”.[34] A similar position can be found in non-reductive materialism, which recognises the struggle between individual agency and social hierachy in cultural production and views neither as completely determinant.

On the other hand, James Christie & Negri Degrimencioglu’s ‘Cultures of Uneven and Combined Development’ advance Trotsky’s notion of uneven and combined development (UCD) in the field of IR as a means of fleshing out the “lived reality of inter-societal interaction”, “articulating the relationship between cultural production and the historical backdrop of neoliberal globalisation”.[35] Whilst, more broadly, UCD has been deployed as a Marxist theory of IR which emphasises “the interactive multiplicity of human society… [as] a fundamental source of creative change and innovation in human history”[36], Christie & Degrimencioglu’s specific use of the concept in regards to culture can be seen as a counterpoint to the top-down approaches espoused by Gienow-Hecht and the like. Highlighting the radical importance of individual exchanges and dynamism of the international as defined by the ‘universal law of unevenness’, UCD in culture is particularly useful in illustrating the complex relationship between the individual and global power relations and aims to more closely capture the lived reality of the international in the age of globalisation. In this way, UCD directly speaks to the pessimistic outlook on globalisation maintained by Hannerz as well as Radano & Olaniyan, emphasising the potential for global encounters to give rise to new yet more causally important identities and communities. Similar dynamics can be perceived in Inayatullah’s concept of “innovative traditionalism”[37] and cultural studies’ notion of “cultural hybridity”[38], which both explore the web of interactions between global and local cultures and again highlight the importance of individual and cross-cultural exchanges in creating new cultures. While it has been debated whether UCD can explain international causality completely in and of itself, without relying on “undigested” concepts from other theories of IR[39], its core belief in recognising the importance of unevenness and combination in international reality still holds value. As such, this study advances UCD as a bottom-up model of music in IR, facilitating a conversation between this and top-down approaches such as Gienow-Hecht’s ‘nation-branding’ in the case of hip hop music to explore the benefits of recognising bottom-up flows in explaining the international. Ultimately, it aims to draw a model of music that most closely reflects the positions of Blanchard and non-reductive materialism, integrating and recognising the simultaneous functions of top-down forces such as agenda power relations as well as bottom-up forces such as individual agency and innovative traditionalism to explain the lived reality of IR in a manner similar to Entman’s Cascade Model of media.

Hip Hop, A Tale of ‘Imitation and Innovation’

The emergence of hip hop as a musical genre itself is powerfully embedded in global historical power relations, with the first hip hop party being thrown in the Bronx, New York by Jamaican immigrant Kool Herc.[40] Having been exposed to the sound system culture and practice of toasting (in which DJs would deliver words or speeches over their reggae or dancehall riddims) in his native Jamaica, Herc attempted to replicate this in the context of New York by throwing paid music events in his Bronx residence. Driven to emulate the energy found in Jamaica’s dance hall parties, Herc made a significant musical intervention by playing two records simultaneously to focus on and extend the high-energy drum sections found in certain songs (which would become known as a break). The complex, dynamic rhythms featured in these breakdowns were particularly appealing to dancers, whilst Herc would introduce the records with rhyming phrases in a similar manner to how Jamaican DJs would toast over their sound systems. This high-energy dancing and punctuation of the beat with rhymes would become the blueprint to hip hop, evolving into breakdancing and rapping respectively. However, in contrast to this directional flow of Jamaican musical influences contributing to the emergence of hip hop in America, country music was also a significant influence in the emergence of ska and rock-steady music in Jamaica.[41] During the 1920s and 30s, while Jamaica was still a British colony, its radio infrastructure was little developed and broadcasts from American radio stations such as the country station WLAC from Gallatin, Tennessee were much more easily accessible. With country music being so widely distributed across Jamaica, its musical features began to filter into their creative outputs: the country fiddling of American artist White Rum Raymond can be heard on early Kingston recordings such as the Maytals’ ‘Get Ready’ or the Paragons’ ‘The Tide is High’, while other artists performed outright renditions of country classics in ska style. These influences on Jamaican music can be heard right through to the modern day with Freddie McGregor’s cover of country artist Roger Miller’s ‘King of the Road’ releasing in 2011.[42] Given that these upbeat ska and two-tone rhythms evolved into the slightly more energetic reggae and dancehall ‘riddims’ in Jamaica over the 1960s, a picture of hip hop as emerging out of a series of musical exchanges between the US and Jamaica begins to take shape. Manifesting certain power relations, such as the lack of development in colonial Jamaica’s radio infrastructure relative to the US, these exchanges gave birth to novel forms of expression and highlight the value of individuals attempting to make sense of their environments in light of these constraints.

These cycles of exchanging and innovating (or imitating and innovating) are evident throughout the history and spread of hip hop. Many hip hop scenes in other countries started with outright imitation of American hip hop aesthetics before growing into more localised representations of particular environments. Early British rap groups such as Demon Boyz notably performed in American accents before eventually giving way to the London Posse’s ground-breaking use of cockney slang in their rhymes and now a whole slew of individualised British styles of hip hop music today. Similarly, Yin T’sang’s ‘Welcome to Beijing’, widely regarded as one of China’s first hip hop songs, is a clear inversion of seminal hip hop track ‘Straight Outta Compton’ by N.W.A and is a far cry from the heavy use of Chinese images and samples in contemporary Chinese rapper Gai’s ‘Hotpot Soup’, for example. Even deeper, Hyun Jin-Young’s performance on South Korean TV in 1992 is widely regarded as the countries’ first national exposure to the genre, yet its chorus is made up of the English phrase “jump” being repeated multiple times.[43] In this way, hip hop’s spread plots the importance of chance global exchanges and individuals attempting to maintain value in response to them.

Nonetheless, this sense and value-making in response to dominant global flows is also itself causally potent, given hip hop’s close ties to political and socially-conscious messages. Blanchard charts the genre’s historical relationship to the West African griot tradition, in which travelling poets would spread knowledge in the accessible form of spoken word and took on the role of “keepers and purveyors of knowledge”.[44] The significance of words and oral knowledge to West African tradition is particularly evident in the philosophical concept of nommo, encapsulating the “animative ability of words and the delivery of words to act upon objects, giving life”.[45] This historical connection is then traced through to the word games employed by African-Americans “as a form of resistance to systems of subjugation and slavery”.[46] These complex rhyming and encoded speech patterns allowed slaves to communicate beneath the eyes of their white slave masters- put in plain terms, hip hop journalist Davey D states that the slaves “did what modern-day rappers do—they flexed their lyrical skillz”.[47] Famously termed “CNN for black people” by Public Enemy’s Chuck D[48], the social function is hip hop has survived- despite constraints- throughout the history of the genre, Grandmaster Flash’s gritty no-holds-barred depiction of inner city reality in ‘The Message’ elevated issues of poverty to a completely new level, being dubbed NME’s top track of the year in 1982.[49] More recently, Jay Z’s ‘the Story of OJ’ used the genre to express similarly potent messages, utilising samples from Nina Simone’s ‘Four Women’ and cartoon images emphasising black stereotypes, its lyrics explore black people’s role in American culture and the USA’s double standards towards black people, such that fame can transcend race to the point where OJ Simpson can declare “I’m not black, I’m OJ”.[50]

Overall, hip hop’s spread through cycles of imitation and innovation not only powerfully highlights the role of individual sense-making in response to global and historical power relations but also how this sense-making is causally potent, becoming a vehicle of expression for issues specific to different groups. Despite the constraints of institutional forces being evident, such as in colonialism and slavery, this ‘tale’ highlights individuals’ struggles to maintain value in spite of them- an interaction that is better captured from the bottom-up perspective of UCD, rather than top-down models of nation branding. The particularities of these dynamics will be explored further in a close look at the spread of hip hop globally.

A Close Look at the Global Spread of Hip Hop

‘Chinese Style’ Hip Hop

The ability of hip hop to take individualised and localised meanings is perhaps no more apparent than in the genres spectacular rise to the mainstream in China. Despite strong central constraints on the import and distribution of hip hop CDs over the 2000s, a burgeoning Chinese rap scene began to take hold as American records trickled through the net and found their way into local hands.[51] Many artists describe their work as struggling against central agendas and staying active “against the surveillance state”.[52] However, the period of the 2000s also saw a turning point in the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) stance towards culture, shifting towards “developing cultural industries” and using Chinese creativity to “project soft power”.[53] Perhaps inspired by this changing attitude towards culture, and with cultural exports being already mobilised to great success in South Korea, the show ‘the Rap of China’ premiered on Chinese TV network iQiyi in late 2017, pitting rappers from around the country against each other in elimination-style challenges in order to determine a winner at the end of the series. Many spotted similarities between ‘the Rap of China’ and the already-popular South Korean rap show ‘Show Me the Money’, with widely circulating rumours that iQiyi had purchased the rights from South Korean network mNet.[54] Nonetheless, the show was immensely popular, being viewed over 100 million times in the first four hours since it aired, accumulating 1.3 billion views in just over a month.[55] Being widely credited with elevating hip hop to China’s mainstream, ‘the Rap of China’ was immediately followed by a series of controversies: news began to emerge in early 2018 of China’s short-lived “hip hop ban”, with the State Administration of Press, Publication, Film and Television of the People’s Republic of China (SAPPRFT) announcing that it “now specifically requires that programs should not feature actors with tattoos [or depict] hip hop culture”.[56] Meanwhile, the show’s joint winners both soon found themselves involved in conflict, with PG One’s career being promotly halted by accusations of drug use and sexual misconduct and fellow winner (the ‘gangsta god’) Gai being pulled from another Chinese reality show ‘Singer’ amidst the hip hop crackdown.[57] This interaction potently echoes Shaun Chang’s view that, amidst these changing relations with cultural industries in Chinese society, “government policies are often in direct contradiction with the interests of state-run institutions and creative entrepreneurs”.[58] Here Chang is describing a sort of run-away effect of the shifts in cultural production that were initiated by the CCP, as “Chinese society… is seizing the opportunity to move towards a more creative and diverse future”.[59] What SAPPRFT perhaps didn’t take into account, however, was the transformations recognisable hip hop sonics encountered as they disseminated throughout Chinese society. Featuring samples from traditional Chinese instruments and heavily drawing Chinese imagery in their lyrics, recent years have seen the emergence of what is referred to as ‘Chinse style’ rap in China. Consider, for example, the lines:

The entire Jiang-hu is allowing me to break through, my life is like a song. Nothing can take it away; karma comes and go in the flow of Taoism

on the chorus of the cult classic ‘the Flow of the Jiang-Hu’ by C-Block featuring Gai, amidst visuals of the artists floating on a Chinese cargo ship on the Jiang-hu river.[60] Through the journey of hip hop to China’s mainstream we not only again see the entanglement of music in wider power relations, but also the malleability of creative expression to respond to these conditions in novel ways. Where Radano & Olaniyan’s ‘Audible Empire’ would perhaps understand the spread of hip hop to China in terms of cultural homogeneity and imperialism, and Gienow-Hecht would see it in terms of one-directional nation branding, hip hop artists in China have fused globalised ideas with localised representations, creating a whole new medium of expression and cultural commodity. This sort of interaction is better captured under the cultural studies notion of cultural hybridity and can be teased out through the web of interactions between individual and structure laid out by Christie and Degrimencioglu’s cultures of UCD. Inadvertently, this dynamic played itself out on ‘the Rap of China’ as MC Jin, the first Asian-American to gain popularity as a rapper and widely celebrated as a pioneer amongst China’s native hip hop artists, was eliminated whilst participating in the show disguised as ‘Hip Hop Man’. Despite progressing in the competition thanks to his experience as a rapper in America, it was Jin’s evident difficulty when rapping in Mandarin compared to the native contestants that ultimately saw him eliminated from the show. In what seemed like a coming-of-age moment for Chinese hip hop as a whole, ‘Hip Hop Man’ removed his mask and was immediately met with an outpour of emotion from the other contestants as they recognised who he was- even the ‘Gangsta God’ Gai himself broke down in tears. The message was clear: the Chinese rap scene had matured to the point where it had outgrown its roots in American hip hop culture. It had become a distinct tradition of its own.[61]

Hip Hop and the Arab Spring

Meanwhile, over the last 10 years the Middle East has seen hip hop become particularly embroiled in institutional power relations. The rap song ‘Rais Lebled’ (‘Head of State’) by Tunisian rapper El General was released one month before the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi that was widely regarded as the impetus for Tunisia’s Jasmine Revolution.[62] Its lyrics’ focus on poverty and scathing critique of Tunisian President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali found strong resonance with the demands of the protestors and ‘Rais Lebled’ soon became known as the “anthem of the revolution”, being distributed widely online via social media and being chanted at demonstrations.[63] As the Jasmine Revolution began to spread to other countries in a chain reaction that would come to be known as the Arab Spring, rap songs from other countries also took on revolutionary meaning. Similarly, ‘Calling the Libyan Youth’ by Libyan hip hop artist and activist Ibn Thabit utilised the internet to address issues of poverty and injustice, while other tracks addressing then-President Colonel Gadaffi took on a role at protests similar to that of ‘Rais Lebled’ to the point where one publication even described Ibn Thabit as “the beat of the revolution” in Libya.[64] Finally, the content of Palestinian rap group DAM has garnered notable attention for being involved in the politically charged climate between Israel and Palestine. Driven by the politically charged drive-by shooting of a close friend in 2000, contributing artist Tamer Nafar now organises hip hop shows to rally support for threatened Palestinian settlements and often faces criticism and imminent shutdown from across the Israeli border.[65] What is common among all these Middle Eastern rappers is their use of the medium to not only reflect their personal reality but also become empowered within it, aided by use of new technologies such as the internet and social media that were already heavily utilised in the early stages of the Arab Spring.[66] It is particularly telling that the World Music’s ‘Rough Guide to Arabic Revolution’ compilation album features rap songs from all of these artists.[67] Given the dense expressive capacity and easily appropriated nature of the hip hop medium, coinciding with increasing use of global communications technologies such as the internet and social media more broadly[68], the content of Middle Eastern rappers’ representations were able to find resonance with and inspire reactions from their wider social community.

Hip Hop and Commercialisation in South Korea

Finally, given the heavy commercialisation of its cultural industry, hip hop in South Korea provides considerable insight into how artists are affected by commercial forces. The 1990s saw a shift in South Korean policy towards culture from an approach based around political control towards viewing cultural industries as central to their export-focussed development strategy and, today, South Korea’s Ministry of Culture serves to promote Korean culture abroad and push hallyu (Korean Wave) by pouring funds into musical projects.[69] The Ministry is widely credited for the spectacular success of ‘KPop’ bands abroad (with one of the most popular such KPop groups BTS setting a slew of world records[70]), funding translation of Korean pop songs into a range of commonly-spoken languages and even contributing to Big Hit Entertainment’s recent free BTS-themed Korean-language learning platform in an attempt to boost consumption of Korean culture by foreign audiences.[71] This strong commercial directive in culture is also evident in South Korea’s hip hop scene, which is dominated by a small handful of labels with global reach and considerable buying power. Moreover, the aforementioned mNet reality TV Show ‘Show Me the Money’ has over nine seasons practically become a staple of South Korean hip hop, with many of the countries’ most popular rap artists featuring on the show as either a contestant or a judge and the progress of contestants being measured in the form of profit.[72] This strong commercial presence in hip hop, a genre hitherto casted as a potent vehicle for individual expression, immediately gives rise to a conflict between marketability and authenticity. One particular contestant on ‘Show Me the Money’, Woo Wonjae, highlights this conflict more than any other- previously unknown on the South Korean hip hop scene, Wonjae made his debut on the reality show with his signature gritty portrayals of personal struggle, growling voice and unkempt appearance. Soon being catapulted to fame as he progressed to the final rounds of the show, Woo Wonjae signed to Jay Park’s AOMG record label in 2017, one of the biggest labels in the country. Despite seemingly retaining his artistic connection to personal struggle in his first LP release ‘Anxiety’ after signing to AOMG, subsequent singles released by Wonjae feature him heavily stylised in high-budget videos, a far cry from the gritty, unkempt rapper that debuted a year earlier. The following years also saw him feature on a number of verifiable pop hits such as ‘I’MMA DO 아마두’, designed for mainstream appeal and commercial success.[73] It seems that commercial forces can both constrain and provide a platform for artistic expression, as Wonjae’s participation in ‘Show Me the Money’ both opened up his gritty portrayals to a vast audience but simultaneously saw a watering down of this gritty aesthetic.

This conflict between individual expression and commercial forces is also explored in depth by Blanchard’s ‘The Social Significance of Hip Hop’, detailing how the gradual buying up of local radio stations in America by large conglomerates led to a homogenisation of rappers’ representations.[74] Exhibiting a more nuanced position is Anamik Saha’s ‘Locating MIA: ‘Race’, Commodification and the Politics of Production’, argues that commercial forces can both have a trivialising and empowering force on artistic authenticity, drawing on the career of female British-Sri Lankan artist MIA to argue that this ultimately depends on how artists navigate these commercial forces. Fighting against dominant essentialist stereotypes of the Asian identity in the media, MIA is viewed as an exceptional cultural entrepreneur in managing to “express a disavowed Asian identity without becoming trapped in the marginal space through which Asian culture is excluded”.[75]

Overall, from China to the Middle East to South Korea, these discussions have highlighted how hip hop artists struggle to maintain meaning and value in the face of their commercial, political and physical reality. Their careers and musical motifs embroil themselves in dominant power relations, reflecting and expressing both socially and globally important forces, as well as becoming causally important forces themselves.

Hip Hop in its Wider Context

In order to properly determine to what extent hip hop challenges dominant understandings of music in IR, however, it needs to be considered in its wider historical and musical context. Considering hip hop in the context of other genres, Inayatullah’s study into the emergences of afro-beat and bossa nova are particularly enlightening. Both of these genres’ emergences are traced in relation to global power flows, with Nigerian artist Fela Kuti drawing on American jazz and funk music as well as West African highlife to create a style that was both “traditional and modern; local and global” in afro-beat.[76] Similarly, bossa nova was a manifestation of historical relations specific to Brazil, fusing influences from the Congolese rumba and Senegalese mbalax that were tied together through colonial flows to create “something authentically Brazillian [to offer] to the rest of the world”.[77] Not only does Inayatullah highlight the embroilment of artists and musical motifs in global power relations, however, but his study also features music’s ability to be appropriated by different communities and messages. In synthesising “the global, cosmopolitan and contemporary with the local, indigenous and traditional” to create a novel musical tradition,[78] Fela Kuti exhibits the same kind cultural hybridity that Chinese rappers embodied in the emergence of ‘Chinese style’ rap. Clearly, the empowerment of individualised experiences and expression of globally significant relations are not specific to the hip hop genre itself, given that these same traits are present in other musical styles such as afro-beat or bossa nova.

Meanwhile, Radano and Olaniyan’s ‘Audible Empire’ and Ramel and Prevost-Thomas’ ‘Music and Diplomacy’ studies into the role of music in IR focus primarily on historical periods- namely early imperialism and early-modern Europe respectively. Richard Leppert’s study into ‘Music, Representation and Social Order in Early-Modern Europe’ describes music in this period as “predominately… [responding] to the needs of two groups: those in charge of organised and largely hegemonic religions… and the hegemonic social classes”.[79] Indeed, these historical periods in particular had significant social barriers to music-making and enjoyment, with musical instruments being largely accessible only to societies’ elite and songs mainly being composed by and for these audiences. Ahrendt’s ‘Diplomatic Viol’ especially highlights this privileged relationship, exploring the explicitly diplomatic function that the viol played in early-modern Europe amidst the culture of court orchestras.[80] Similarly, given the social status that accompanied music in early-modern Europe, Radano and Olaniyan describe how European imperialists projected their loaded conceptions of music onto colonised African communities and cast their difference as inferiority.[81] Given these specific social relations of music in this historical period, these authors emphasis on the national, diplomatic and broadly top-down functions of music in IR is understandable. However, this does not mean that bottom-up forces in music are completely absent across history: Leppert’s historical musical analysis also describes how “among the lower social orders in Europe… [music] benefitted communities as a means of defining and stabilising their socio-cultural locus and inter-subjectivity”.[82] In other words, what this discussion has previously highlighted as hip hop’s role in individualised and localised meaning making in the face of dominant power relations can also be witnessed in other genres across history. In conjunction, it is important to note the emergence of Ghanaian highlife music as a response to imperial constraints on music making, arising as West African musicians began to play traditionally African rhythms on the European instruments brought over by colonialists and creating a completely novel musical tradition in the process.[83] As such, while top-down constraints in the form of social power relations and colonial enterprises vary in severity over history, the radical capacity of music to empower individualised experiences, make meaning in the face of dominant constraints and become causally important themselves from the bottom-up seems both present across time and genre.

Nonetheless, in light of this, hip hop still emerges as a particularly well-placed case study to challenge existing understandings of music in IR since it more than any other genre and historical period emphasises these bottom-up flows. Compared to, say, a court violinist in early-modern Europe or a West African highlife artist in times of imperialism, there is a far lower barrier of entry to becoming a rapper today- as highlighted by Tunisian rapper El General, one does not need to be known or trained as a musician to become a socially significant cultural entrepreneur. This feature is only further entrenched by the fact that hip hop has historically been associated with socially and politically significant messages, considered in its context of theWest African griot tradition and systems of slavery. Moreover, given that music consumption has rapidly transitioned to the digital realm over the last 20 years[84] in the same period that hip hop music has rapidly spread around the globe, rappers have both unprecedented access to music and platforms for their own creations (for example, evident in how Middle Eastern rappers such as El General and Ibn Thabit used the internet to enable their songs to become revolutionary anthems). This discussion has also highlighted a final way in which technology has coincided with the spread of hip hop as an expressive medium- already immediately having a dense expressive capacity thanks to its heavy emphasis on lyricism, hip hop can carry yet further expressive content in its close relationship to the practice of sampling. Heavily utilised by Chinese rappers in the formation of ‘Chinese style’ rap, sampling allows the incorporation of virtually unlimited musically and culturally significant sounds into the genre and further enables hip hop as a vehicle for localised meaning.

Thus, while not entirely inherent in the genre itself, both musical and historical feature coincide in hip hop to make it well-placed to empower individual experiences and localised meanings and, in doing so, challenge existing understandings of music advanced by the likes of Gienow-Hecht, Ramel and Prevost-Thomas, and Radano and Olaniyan. Outlined here are four features of the hip hop medium in particular that make it particularly poised for this role: a) its unprecedentedly low barrier to entry; b) close ties to modern technology; c) strong political history and, d) dense expressive capacity

Implications for Understandings of Music in IR

The dynamics outline in this discussion highlight the simultaneous functioning of top-down (institutional and commercial) and bottom-up (the role of individual agency in meaning-making in the face of these flows) forces in music in IR. Particularly emphasised in the case of hip hop is the radical role of this individual agency in reflecting, responding to and becoming causally empowered within their commercial, political and physical reality, a dynamic that is not properly accounted for in the top-down understandings of music in IR advanced in nation branding and ‘Audible Empire’. Thus, hip hop serves to challenge these existing understandings of music in IR. Rather, the dynamics highlighted by a close study of hip hop’s emergence and global spread are better explained by bottom-up models such as cultures of UCD, innovative traditionalism and cultural hybridity- not only more accurately capturing the reality of music in IR (in fighting against notions of global homogeneity and instead recognising individual creativity as a radical element) but also generating a more refined and diverse look into the reality of IR itself. Through emphasising the uneven yet combined nature of world development from an individual perspective, cultures of UCD illustrates how music tends to hybridise with rather than submit to dominant global forces, emerging as a means of meaning-making in the face of these power relations. By focussing on how individuals and communities come into contact with, react to and make sense of global forces we shift these individual perspectives to the forefront of studies of IR. Doing so potently answers Selbin and Nayak’s call to ‘decentre IR’ and not simply insert “case studies from around the world”[85], instead recognising alternative means of meaning-making and, by studying their representations themselves, confronts the “way we talk about, share and experience these narratives”.[86] In this way, hip hop is a particularly useful case study in the wider ‘aesthetic turn’ in IR, more than any other genre empowering individual experiences through its unprecedentedly low barrier to entry whilst its dense expressive capacity and focus on socially important content provides a wealth of analysable material for studies of representation. Being used here to not only challenge but formulate responses to dominant understandings of music in IR, the case study of hip hop appears to potently fulfil Bleiker’s conclusion that aesthetic studies “generate a more diverse but also more direct encounter with the political”.[87]

Overall, in emphasising the importance of individual experience and the causal power of creativity beneath the visible flows of power in IR this study emphasises the importance of ‘keeping it real’ over ‘keeping it realist’ in studies of the discipline.

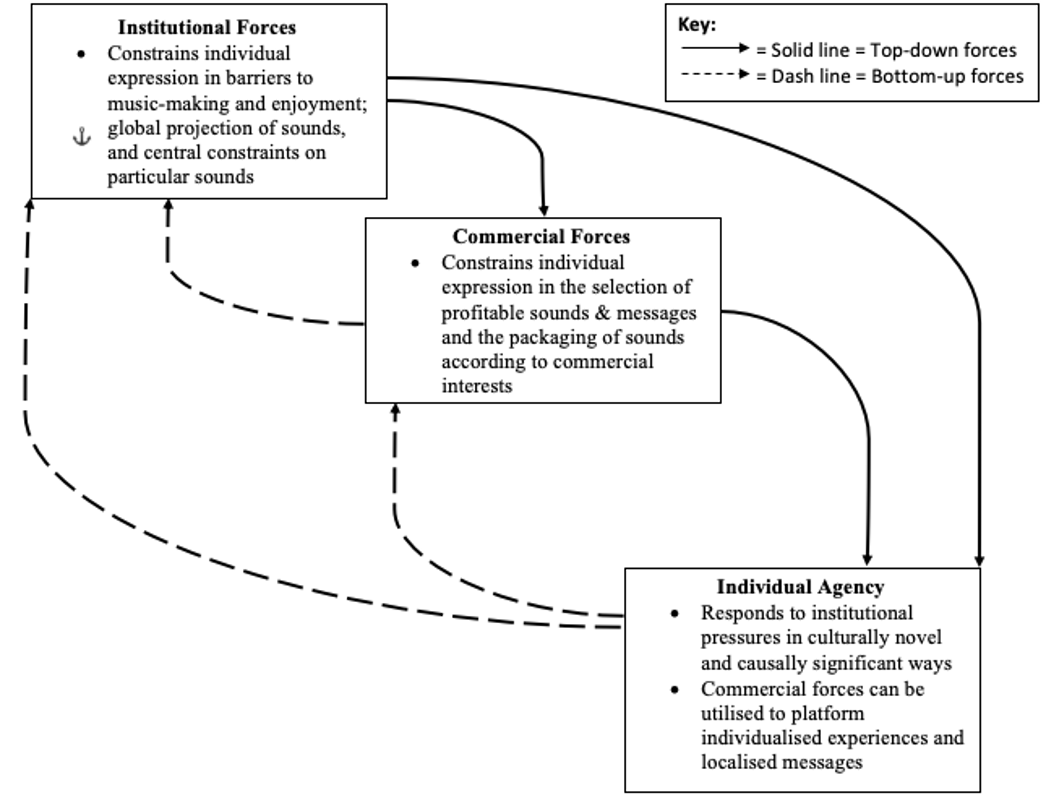

The conclusions drawn from this discussion can be plotted on a modified version of Entman’s Cascade Model of Media (Figure 2) to provide a rough functional model of how individual agency interacts with dominant institutional and commercial forces in IR.

Overall, Figure 2 illustrates what this discussion has found as the simultaneous functions of top-down and bottom-up forces in music in IR. Individuals and cultural entrepreneurs are both constrained by and react to institutional and commercial forces but ultimately what is highlighted here is the struggle of individuals to maintain meaning and value in the face of these constraints, a dynamic that is little recognised in studies of music in IR. Institutional forces are evident in the social barriers to music-making and enjoyment (as emphasised in studies by Gienow-Hecht, Ramel and Prevost-Thomas, and Radano and Olaniyan); global projection of sounds by dominant states (for example, the influences of country music on twentieth century Jamaican musical traditions or the global projection of hip hop), and central control on particular sounds (as seen in China’s attempt to control hip hop culture). Commercial forces are present in the selection and packaging of sounds according to commercial interests- witnessed in studies by Saha as well as in the case of South Korea’s ‘Show Me the Money’, where a conflict between commercial interests and artistic authenticity began to emerge. Flowing against these top-down constraints, however, is the radical role of individual agency in responding to these forces: creating novel musical traditions that reflect individualised and localised meanings (abundantly present in hip hop’s emergence and global spread in cycles of imitation and innovation, from Kool Herc’s sense-making of global & historical power relations to the fusing of musical genres in ‘Chinese style’ rap as well as afro-beat and bossa nova) and also becoming causally important forces themselves, seen in the revolutionary role rap songs took on during the Arab Spring.

Deeper still, national agendas may guide use of commercial forces (for example the deployment of cultural industries in China and South Korea as a tool in the projection of soft power) but also commercial forces can act independently of and even directly against agendas (evident in the controversy immediately following the airing of ‘the Rap of China’s’ first season and what Chang countenances as the Chinese Ministry of Culture’s inability to completely control the content of cultural entrepreneurs). Ultimately, this model most closely reflects the positions expressed by Blanchard, Inayatullah and cultural hybridity in illustrating the simultaneous functioning of top-down and bottom-up forces and teasing out of the dynamics of interaction between individuals and power relations at the global level, to which the understanding of is greatly aided by concepts such as Christie & Degrimencioglu’s cultures of UCD. Through use of these concepts, the role of music emerges as a source of innovation and individual meaning-making in the face of dominant global power relations rather than a pure manifestation of them.

Concluding Remarks

Emphasising the role of individual agency and bottom-up flows, this study finds that hip hop powerfully challenges existing understandings of music in IR. However, this is not because individual agency is exceptional to the genre itself but rather because of certain features of the genre (such as its ease of access and dense expressive capacity) coincide with certain concomitant external factors (such as recent developments in global communications technology and information sharing) to highlight a radical role of music and individual creativity that is evident across time and all genres. There is a deeper significance in recognising these bottom-up flows and elevating the importance of individual perspective in studies of IR in that it generates both a more refined and diverse understanding of international reality- which this study suggests to be the other IR that we as students of the international should concern ourselves with.

Further Considerations

Nonetheless, in attempting to facilitate a broad discussion between top-down and bottom-up approaches to music in IR, this study has taken a rather sparse look at the precise ways in which individual and structural forces interact. Further study could benefit from following Saha’s ‘Locating MIA: ‘Race’, Commodification and the Politics of Production’ in focussing more closely on how individual artists embroil themselves in and react to relations of power.[88] In particular, the roles of technology, historical colonial forces and notions of shared identity and difference have only been touched on lightly in this discussion and would need to be more deeply explored in order to provide a more detailed functional model of music in IR. Similarly, this study moves rather sweepingly between analyses of hip hop in various countries, brushing over for example a deeper investigation into the particular factors that contributed to the Arab Spring or China’s relationship with its cultural industries. Further studies would greatly benefit from a closer look at these country-specific factors. However, insofar as providing a rough roadmap for these interactions and a vague mission statement for studies of music in IR, Figure 2 can be seen as a reasonable starting point. Each case study outlined in the discussion has a wealth of information to be analysed- simply advancing musical motifs and biographical trivia as useful material in studies of IR immediately opens the door to a plethora of further investigation into how individual experiences and perspectives can generate insight into international reality.

Figures

[Figure 1. Entman’s Cascade Model- conceptualises the flow of information through society as a chain from administration right down to individuals at the bottom. Each level is seen to have causal agency in the shaping and dissemination of information and, as such, no actor is completely determinant in how information will be digested and perceived.]

[Figure 2: Modified Version of Entman’s Cascade Model]

Footnotes

[1] Blanchard (1999) ‘The Social Significance of Rap & Hip-hop Culture’ para.14

[2] Wendt (1982) ‘The Agency-Structure Problem in International Relations Theory’

[3] Bleiker (2001) ‘The Aesthetic Turn in International Political Theory’ p.515

[4] Ibid. p. 510

[5] Ibid. p. 511

[6] Selbin and Nayak (2010) ‘Chapter One / Introduction’ in Decentring International Relations, p. 5

[7] Ibid. p 15

[8] Ibid. p.10

[9] Selbin and Nayak (2010) ‘Chapter Two / Indigeneity’ in Decentring International Relations

[10] Bleiker (2001) ‘The Aesthetic Turn in International Political Theory’ p.523

[11] Blanchard (1999) ‘The Social Significance of Rap & Hip Hop’ para. 5 – see also section 2.1.

[12] Gienow-Hecht (2016) ‘Chapter 14: Nation Branding’ p.233

[13] Ramel and Prevost-Thomas (2018) ‘Introduction: Understanding Musical Diplomacies – Movements on “Scenes”’ p.1

[14] Inayatullah (2016) ‘Gigging on the World Stage: Bossa Nova and Afrobeat After De-Reification’

[15]Ibid. p. 523-525

[16] See, for example: Margolis (1978) ‘Persons and Minds: The Prospects of Non-Reductive Materialism’

[17] See, for example: Albert and Paez (2012) ‘Cultural Hybridity’

[18] Hoge, James F. (1994), ‘Media Pervasiveness’ p.137

[19] Robinson, Piers, (1999) ‘The CNN Effect: Can the News Media Drive Foreign Policy?’ p.301

[20] Chomsky, Noam & Herman, Edward (1988) ‘Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media’

[21] Entman, Robert (2003) ‘Cascading Activation: Contesting the White House’s Frame After 9/11’

[22] Solomon PM ‘Hip Hop Around the World’ database, [Web Link: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1aijM18O3bS8UTni7RR8Te-6q06x37ex3cm5JslYGmfE/edit#gid=0, Last Accessed 28/03/20, Published 09/03/20] See: Appendix 1

[23] Ramel and Prevost-Thomas (2018) ‘Introduction: Understanding Musical Diplomacies – Movements on “Scenes”’ p.1

[24] Ahrendt (2018) ‘The Diplomatic Viol’

[25] Gienow-Hecht (2018) ‘Of Dreams and Desire: Diplomacy and Musical Nation Branding since the Early Modern Period’

[26] Ibid. p. 259-274

[27] Radano and Olaniyan (2016) ‘Introduction: Hearing Empire – Imperial Listening’ in Audible Empire: Music, Global Politics, Critique p. 13

[28] Ibid. p. 13

[29] Adorno as quoted by Radano and Olaniyan (2016) ‘Introduction: Hearing Empire – Imperial Listening’

[30] Hannerz (1997) ‘Scenarios for Peripheral Cultures’ p.108

[31] Salois (2015) ‘Connection and Complicity in Global South: Hip Hop Musicians and US Cultural Diplomacy’

[32] Ibid. p.416

[33] Blanchard (1999) ‘The Social Significance of Rap & Hip Hop’ para. 7

[34] Ibid. para. 12

[35] Christie and Degrimencioglu (2019) ‘Introduction: Why Cultures of Uneven and Combined Development?’ in Cultures of Uneven and Combined Development: From International Relations to World Literature p.13-14

[36] Rosenberg, Justin (2016) ‘Chapter 2: Uneven and Combined Development: “The International” in Theory and History”P.30

[37] Inayatullah (2016) ‘Gigging on the World Stage: Bossa Nova and Afrobeat After De-Reification’ p.525

[38] See, for example: Albert and Paez (2012) ‘Cultural Hybridity’

[39] Callinicos, Alex and Rosenberg, Justin (2008) ‘Uneven and combined development: the social-relational substratum of ‘the international’? An exchange of letters’ p.84

[40] For a full discussion of Kool Herc’s role in the birth of hip hop, see: The Source Magazine ‘Today in Hip Hop History: Kool Herc’s Party at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue’ [Weblink: https://thesource.com/2018/08/11/today-in-hip-hop-history-kool-hercs-party-at-1520-sedgewick-avenue-45-years-ago-marks-the-foundation-of-the-culture-known-as-hip-hop/; Published: 11/08/18, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[41] Redbull Music Academy ‘Country Music in Jamaica’ [Weblink: https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2015/05/reggae-country-feature; Published: 25/05/15, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[42]Ibid. Also, see: Appendix 2

[43] `See: Appendix 2

[44] Blanchard (1999) ‘The Social Significance of Rap & Hip Hop’ para. 5-15

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47]Ibid.

[48] Ibid.

[49] NME ‘Albums and Tracks of the Year – 1982’ [Weblink: https://www.nme.com/bestalbumsandtracksoftheyear/1982-2-1045396; Published: 10/09/16; Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[50] Billboard.com ‘Songs that Defined the Decade: Jay-Z’s “The Story of OJ”’[Web Link: https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/songs-that-defined-the-decade/8543924/jay-z-story-of-oj-songs-that-defined-the-decade; Published: 21/11/19, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[51] Goldsmith and Fonseca (2019) ‘Introduction’ in Hip Hop Around the World: An Encyclopaedia P.xxxiii

[52] The Atlantic ‘Chinese Rappers Take on the Surveillance State’ documentary [Weblink: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DLHmo95OD9g&t=539s, Published: 11/09/19, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[53] Chang (2014) ‘Great Expectations: China’s Cultural Industry and Case Study of a Government-Sponsored Creative Cluster’ p.264-265

[54] South China Morning Post’s YoungPost ‘From Blackface to Plagiarism: Why the Chinese Entertainment Industry Needs a Lesson in Sensitivity for Cultures and Ideas’ [Weblink: https://yp.scmp.com/over-to-you/op-ed/article/110452/blackface-plagiarism-why-chinese-entertainment-industry-needs, Published: 13/09/18, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[55] South China Morning Post ‘”China’s Netflix” Scores Massive Hip-Hop Talent Show Blockbuster thanks to AI’ [Weblink: https://www.scmp.com/tech/china-tech/article/2131206/chinas-netflix-lands-itself-massive-reality-tv-blockbuster-use, Published: 31/01/18, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[56] Time Magazine ‘”Tasteless, Vulgar and Obscene” China Just Banned Hip-Hop Culture and Tattoos from Television’ [Weblink: https://time.com/5112061/china-hip-hop-ban-tattoos-television/, Published: 22/01/18, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[57] SupChina ‘Chinese Rapper Gai Removed from Reality Show Amidst Government Crackdown on Hip-Hop Culture’ [Weblink: https://supchina.com/2018/01/25/chinese-rapper-gai-removed-from-reality-show-amidst-hip-hop-crackdown/, Published: 25/01/18, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[58] Chang (2014) ‘Great Expectations: China’s Cultural Industry and Case Study of a Government-Sponsored Creative Cluster’ p.264

[59] Ibid. p.272

[60] See: Appendix 2

[61] Solomon PM ‘Reorienting Hip Hop: Chinese Style’ [Weblink: https://ioriworld.wordpress.com/articles/, Published: 10/03/20; Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[62] Time Magazine ‘Bouazizi: The Man Who Set Himself and Tunisia on Fire’ [Weblink: http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2044723,00.html, Published: 21/01/11, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[63] Time Magazine ‘El General and the Rap Anthem of the Mideast Revolution’ [Weblink: http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2049456,00.html, Published: 15/02/20, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[64] Aslan Media ‘Ibn Thabit: The Beat Behind Libya’s Revolution’ [Weblink: https://web.archive.org/web/20110909082334/http://www.aslanmedia.com/music/306-music-artist-profile/3065-ibn-thabit-the-beat-behind-libyas-revolution, Published: 08/08/11, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[65] Noisey ‘Hip Hop in the Holy Land’ documentary [3:00-10:00] [Weblink: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m8bWDcW6kYw&t=1069s, Published: 22/12/15, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[66] Brown, Guskin and Mitchell (2012) ‘The Role of Social Media in the Arab Uprising’

[67] World Music Network (2013) ‘The Rough Guide to Arabic Revolution’, see also: Freemuse ‘Hip-hop is a Soundtrack to the North African Revolt’ [Weblink: https://web.archive.org/web/20110926200332/http://www.freemuse.org/sw41490.asp, Published: 20/03/11; Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[68] For more on changing music consumption practices see: Magaudda (2011) ‘When Materiality ‘Bites Back’: Digital Music Consumption Practices in the Age of De-Materialisation’

[69] Kwon and Kim (2013) ‘The Cultural Industry Policies of the Korean Government and the Korean Wave’

[70] Koreaboo ’14 Times BTS Broke World Records’ [Weblink: https://www.koreaboo.com/lists/14-times-bts-world-records/, Published: 16/08/18, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[71]IQ Magazine ‘Big Hit Releases BTS-Themed Korean Language Course’ [Weblink: https://www.iq-mag.net/2020/03/big-hit-releases-bts-themed-korean-language-course/#.Xn9PYdP7QXo; Published: 23/03/20, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[72] For more on Show Me the Money, see for example: The Korean Herald ‘[Hallyu Power] Han Dong-chul, Mastermind of Korean Hip Hop Boom’ [Weblink: http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20160412000578, Published: 12/04/16, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[73] For a contrasting look at Woo Wonjae’s transition from ‘Show Me the Money’ contestant to national pop star, see: Appendix 2

[74] This dynamic is discussed in greater detail in Section 1.5.

[75] Saha (2012) ‘Locating MIA: ‘Race’, Commodification and the Politics of Production’ p.736

[76] Inayatullah (2016) ‘Gigging on the World Stage: Bossa Nova and Afrobeat After De-Reification’ p.524

[77] Ibid. p.525

[78] Ibid. p.535

[79] Leppert (1989) ‘Music, Representation and Social Order in Early Modern Europe’ p.25

[80] Ahrendt (2018) ‘The Diplomatic Viol’

[81] Radano and Olaniyan (2016) ‘Introduction: Hearing Empire – Imperial Listening’ in Audible Empire: Music, Global Politics, Critique

[82] Leppert (1989) ‘Music, Representation and Social Order in Early Modern Europe’ p.28

[83] The Culture Trip ‘A Brief History of Ghanaian Highlife Music’ [Weblink: https://theculturetrip.com/africa/ghana/articles/ghanaian-highlife-music-ashanti-rhythms-and-hiplife-beats/, Published: 12/09/16; Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

[84] For more on changing music consumption practices see: Magaudda (2011) ‘When Materiality ‘Bites Back’: Digital Music Consumption Practices in the Age of De-Materialisation’

[85] Selbin and Nayak (2010) ‘Chapter One / Introduction’ in Decentring International Relations, p.15

[86] Ibid. p 10

[87] Bleiker (2001) ‘The Aesthetic Turn in International Political Theory’ p.511

[88] Saha (2012) ‘Locating MIA: ‘Race’, Commodification and the Politics of Production’

Bibliography

Albert, Lillie & Páez, Mariela (2012). ‘Cultural hybridity’ In J. A. Banks (Ed.), Encyclopedia of diversity in education (Vol. 1, pp. 523-524). SAGE Publications

Blanchard, Rebecca (1999) ‘The Social Significance of Rap and Hip-Hop Culture’ in Ethics of Development in a Global Environment (EDGE)| Poverty & Prejudice [Web Article] https://web.stanford.edu/class/e297c/poverty_prejudice/mediarace/socialsignificance.htm Accessed: 31/10/2018

Bleiker, Robert (2001) ‘The Aesthetic Turn in International Political Theory’ in Journal of International Studies 30:3, Millenium

Brown, Heather; Guskin, Emily, and Mitchell, Amy (2012) ‘The Role of Social Media in the Arab Uprising’, Pew Research Centre: Journalism and Media

Callinicos, Alex and Rosenberg, Justin (2008) ‘Uneven and combined development: the social-relational substratum of ‘the international’? An exchange of letters’, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 21:1, 77 – 112

Chang, Shaun (2014) ‘Great Expectations: China’s Cultural Industry and Case Study of a Government-Sponsored Creative Cluster’ in Creative Industries Journal, 1:3

Chomsky, Noam & Herman, Edward (1988) ‘Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media’, Pantheon Books

Christie, James and Degrimencioglu, Negri (2019) ‘Cultures of Uneven and Combined Development: From International Relations to World Literature’, Brill Sense, Hotei Publishing

Entman, Robert (2003) ‘Cascading Activation: Contesting the White House’s Frame After 9/11’, Political Communication, 20:4, 415-432, DOI: 10.1080/10584600390244176

Gienow-Hecht, Jessica (2016). ‘Chapter 14: Nation Branding’ In F. Costigliola & M. Hogan (Eds.), Explaining the History of American Foreign Relations (pp. 232-244). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goldsmith, Melissa and Fonseca, Anthony (2019) ‘Introduction’ in Hip Hop Around the World: An Encyclopaedia, Pub. Greenwood

Hannerz, Ulf (1997) ‘Scenarios for Peripheral Cultures’ in Culture, Globalisation and the World System: Contemporary Conditions for the Representation of Identity, ed. AD King, University of Minnesota Press

Hoge, James F. (1994), ‘Media Pervasiveness’ in Foreign Affairs, 73:4, p. 136-144

Inayatullah, Naeem (2016) ‘Gigging on the World Stage: Bossa Nova and Afrobeat After De-Reification’ in Contexto Internacional 38:2

Kwon, Seung-Ho & Kim, Joseph (2014) ‘The cultural industry policies of the Korean government and the Korean Wave’ International Journal of Cultural Policy, 20:4, 422-439, DOI: 10.1080/10286632.2013.829052

Leppert, Richard (1989). ‘Music, Representation, and Social Order in Early-Modern Europe’ Cultural Critique, (12), 25-55. doi:10.2307/1354321

Magaudda, Paolo (2011) ‘When Materiality ‘Bites Back’: Digital Music Consumption Practices in the Age of De-Materialisation’ in Journal of Consumer Culture- March Edition

Margolis, Joseph (1978) ‘Persons and Minds: The Prospects of Non-Reductive Materialism’, Pub. D. Reidel

Prévost-Thomas, Cecil and Ramel, Frederic (2018) ‘Introduction: Understanding Musical Diplomacies—Movements on the “Scenes”’; Ahreandt, Rebekah ‘The Diplomatic Viol’, and Gienow-Hecht, Jessica ‘Of Dreams and Desire: Diplomacy and Musical Nation Branding Since the Early Modern Period’ in: Ramel F., Prévost-Thomas C. (eds) International Relations, Music and Diplomacy. The Sciences Po Series in International Relations and Political Economy. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Radano, Ronald and Olaniyan, Tejumola (2016) ‘Introduction: Hearing Empire – Imperial Listening’ in Audible Empire: Music, Global Politics, Critique, Duke University Press

Rosenberg, Justin (2016) ‘Chapter 2: Uneven and Combined Development: “The International” in Theory and History” in ‘Historical Sociology and World History, Uneven and Combined Development over the Longuee Duree’; Rowman and Littlefield

Saha, Anamik (2012) ‘Locating MIA: ‘Race’, Commodification and the Politics of Production’ in European Journal of Cultural Studies 15(6) p.736-752

Salois, Kendra (2015) ‘ Connection and Complicity in Global South: Hip Hop Musicians and US Cultural Diplomacy’ in Journal of Popular Music Studies 27:4

Selbin, Eric and Nayak, Meghana (2010) ‘Decentring International Relations’, Zed Books

Wendt, Alexander (1987). ‘The Agent-Structure Problem in International Relations Theory’ International Organization, 41(3),

World Music Network (2013) ‘The Rough Guide to Arabic Revolution’, Rough Guides

Mediography

Aslan Media ‘Ibn Thabit: The Beat Behind Libya’s Revolution’ [Weblink: https://web.archive.org/web/20110909082334/http://www.aslanmedia.com/music/306-music-artist-profile/3065-ibn-thabit-the-beat-behind-libyas-revolution, Published: 08/08/11, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

Billboard.com ‘Songs that Defined the Decade: Jay-Z’s “The Story of OJ”’[Web Link: https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/songs-that-defined-the-decade/8543924/jay-z-story-of-oj-songs-that-defined-the-decade; Published: 21/11/19, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

Freemuse ‘Hip-hop is a Soundtrack to the North African Revolt’ [Weblink: https://web.archive.org/web/20110926200332/http://www.freemuse.org/sw41490.asp, Published: 20/03/11; Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

IQ Magazine ‘Big Hit Releases BTS-Themed Korean Language Course’ [Weblink: https://www.iq-mag.net/2020/03/big-hit-releases-bts-themed-korean-language-course/#.Xn9PYdP7QXo; Published: 23/03/20, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

Koreaboo ’14 Times BTS Broke World Records’ [Weblink: https://www.koreaboo.com/lists/14-times-bts-world-records/, Published: 16/08/18, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

NME ‘Albums and Tracks of the Year – 1982’ [Weblink: https://www.nme.com/bestalbumsandtracksoftheyear/1982-2-1045396; Published: 10/09/16; Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

Noisey ‘Hip Hop in the Holy Land’ documentary [3:00-10:00] [Weblink: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m8bWDcW6kYw&t=1069s, Published: 22/12/15, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]; Vice Network

Redbull Music Academy ‘Country Music in Jamaica’ [Weblink: https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2015/05/reggae-country-feature; Published: 25/05/15, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

Solomon PM ‘Reorienting Hip Hop: Chinese Style’ [Weblink: https://ioriworld.wordpress.com/articles/, Published: 10/03/20; Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

South China Morning Post ‘”China’s Netflix” Scores Massive Hip-Hop Talent Show Blockbuster thanks to AI’ [Weblink: https://www.scmp.com/tech/china-tech/article/2131206/chinas-netflix-lands-itself-massive-reality-tv-blockbuster-use, Published: 31/01/18, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

SupChina ‘Chinese Rapper Gai Removed from Reality Show Amidst Government Crackdown on Hip-Hop Culture’ [Weblink: https://supchina.com/2018/01/25/chinese-rapper-gai-removed-from-reality-show-amidst-hip-hop-crackdown/, Published: 25/01/18, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

The Atlantic ‘Chinese Rappers Take on the Surveillance State’ documentary [Weblink: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DLHmo95OD9g&t=539s, Published: 11/09/19, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

The Culture Trip ‘A Brief History of Ghanaian Highlife Music’ [Weblink: https://theculturetrip.com/africa/ghana/articles/ghanaian-highlife-music-ashanti-rhythms-and-hiplife-beats/, Published: 12/09/16; Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

The Korean Herald ‘[Hallyu Power] Han Dong-chul, Mastermind of Korean Hip Hop Boom’ [Weblink: http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20160412000578, Published: 12/04/16, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

The Source Magazine ‘Today in Hip Hop History: Kool Herc’s Party at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue’ [Weblink: https://thesource.com/2018/08/11/today-in-hip-hop-history-kool-hercs-party-at-1520-sedgewick-avenue-45-years-ago-marks-the-foundation-of-the-culture-known-as-hip-hop/; Published: 11/08/18, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

Time Magazine ‘”Tasteless, Vulgar and Obscene” China Just Banned Hip-Hop Culture and Tattoos from Television’ [Weblink: https://time.com/5112061/china-hip-hop-ban-tattoos-television/, Published: 22/01/18, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

Time Magazine ‘Bouazizi: The Man Who Set Himself and Tunisia on Fire’ [Weblink: http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2044723,00.html, Published: 21/01/11, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

Time Magazine ‘El General and the Rap Anthem of the Mideast Revolution’ [Weblink: http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2049456,00.html, Published: 15/02/20, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

YoungPost of South China Morning Post ‘From Blackface to Plagiarism: Why the Chinese Entertainment Industry Needs a Lesson in Sensitivity for Cultures and Ideas’ [Weblink: https://yp.scmp.com/over-to-you/op-ed/article/110452/blackface-plagiarism-why-chinese-entertainment-industry-needs, Published: 13/09/18, Last Accessed: 02/04/20]

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- “Fake It Till You Make It?” Post-Coloniality and Consumer Culture in Africa

- Tracing Hobbes in Realist International Relations Theory

- When It Comes to Global Governance, Should NGOs Be Inside or Outside the Tent?

- Cyber War Forthcoming: “It Is Not a Matter of If, It Is a Matter of When.”

- Decolonisation and Violence: What It Takes to Decolonise IR

- Cultural Relativism in R.J. Vincent’s “Human Rights and International Relations”