“No one starts a war – or rather, no one in his senses ought to do so – without first being clear in his mind what he intends to achieve by that war and how he intends to conduct it”, says Clausewitz. If China is going in for “wolf warrior” diplomacy, as described by many observers, what war are “wolf warriors”, the bellicose diplomats and propaganda media machines, fighting? What, in their mind, do they intend to achieve? And how?

Although some may find the hawkish style of Chinese diplomats uncalled for, it is anything but miscalculated or reckless. Think about Hua Chunying, one of the “wolf warrior” diplomats, who in 2018 said that “certain people in the US are sparing no effort to win the ‘Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay’” when rebutting an accusation that the Chinese intelligence agencies have been bugging then President Trump’s iPhones. Less than one year later, she was promoted from Deputy Director to Director of the Foreign Ministry Information Department. Another Foreign Ministry spokesperson, Geng Shuang, who vowed that China would never feel threatened or intimidated when responding to Trump’s tariffs, was elevated to Deputy Permanent Representative to the United Nations last year.

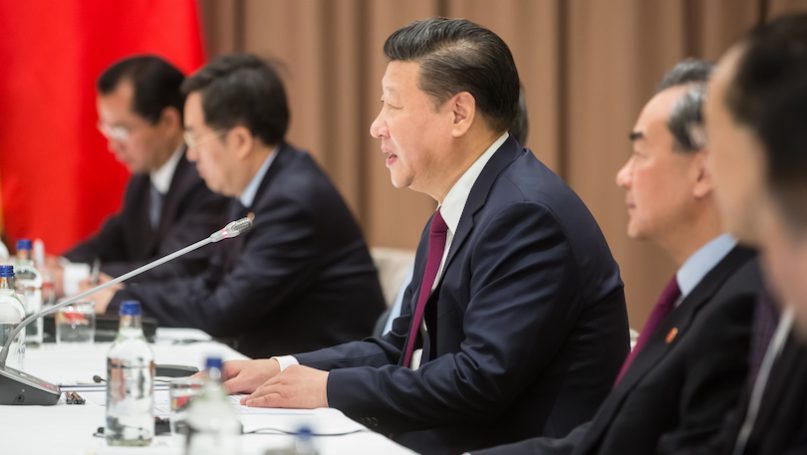

The three years or so “wolf warrior” diplomacy came to a climax last month when Yang Jiechi, China’s top diplomat and a high-ranking communist party member, gave his US counterparts a 16-minute lecture, in which his saying “this is not the way to deal with the Chinese people” has gone viral in China. This official translation is in fact a too mild one. It could have been translated simply, and rather bluntly, to “We Chinese don’t buy it”.

Besides denouncing the “condescending way” of the US, warning against the Thucydides Trap, and framing the bilateral relations as one between a victim and a perpetrator, the diplomats are fervently discrediting the human rights record of the US, which they label as “self-styled judges of human rights” and “self-anointed ‘beacon of human rights’”. Hua also once said that “speaking of abiding by international rules, China is doing a great job while the US has a poor record,” and, she added, “this is a fact recognized by the international community.”

The question, then, is how widely the Chinese view is shared by the international community. When meeting with their visiting counterpart Wang Yi in March, both UAE’s and Bahraini foreign ministers agree with him that many developing countries have suffered unfair treatment over human rights issues, which, in their view, are being politicized and used as a pretext under which some Western countries are interfering in other countries’ internal affairs. A rift seems to be deepening between China-led and Western countries.

Such politics of human rights, however, is nothing new. It is not hard to recall the discord between the US and the Soviet Union in the Cold War. Around the time when Americans adopted the Truman Doctrine to contain Soviet geopolitical expansion, there was also the Universal Declaration of Human Rights accepted by the United Nations General Assembly, though with the abstention of eight countries from the Soviet bloc. The Declaration provided both powers the vocabulary to promote their own versions of human rights diplomacy, resulting in a global contest over the essence of human rights. Perhaps surprisingly, the Soviet Union was a strong advocate of human rights, the right to self-determination in particular, attacking the colonialism of Western countries. Nikita Khrushchev asked rhetorically in 1960, when addressing to the UN General Assembly, that

How is it possible to develop friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples, which is the purpose of the United Nations, and at the same time to tolerate a situation in which, as a result of the predatory policy of the Powers that are strong militarily and economically, many Asian and African peoples can win their right to determine their own fate only at the prince of incredible suffering and sacrifices, only through an armed struggle against the oppressors?

On the other hand, as historian Mary Ann Heiss suggests, the US “missed no opportunity to condemn the hypocrisy embodied in the Soviet Union’s purported concern for self-determination in the Western-controlled dependent territories while engaging in out-and-out repression throughout Eastern Europe, the Baltic States, and Central Asia.” The US preoccupation with denouncing the Soviet impingement of basic rights and freedoms behind the Iron Curtain, however, was at odds with developing countries, which found political and civil rights meaningless if basic living standards were not secured. The American human rights diplomacy even drove them away. Not only the 1960 Declaration on Colonialism could be regarded as a triumph of the anti-imperialist human rights over the Western one, from the 1960s onward, as historian Eric D. Weitz puts it, “the Soviet bloc–Global South alliance largely defined the meaning of international human rights.”

If similarities can be drawn between now and then, it should be, first, both the Soviet Union and China embrace, rather than reject, human rights, at least as seen in its diplomatic discourse. Second, just as the Soviet rhetoric was welcomed by the Global South, Chinese model on human rights is also winning support internationally. For example, 46 countries such as Belarus, Iran, and Russia voiced their support for China’s Xinjiang policies last year, putting emphasis on safety and stability, followed by 70 countries backing China’s implementation of new laws on Hong Kong and urging Western countries to stop interfering in China’s internal affairs this year.

The right to development, the notion of Westphalian sovereignty, and the principle of non-interference are apparently what unite China and its allies. As Wang Yi addressed the United Nations Human Rights Council earlier this year that “the rights to subsistence and development are the basic human rights of paramount importance”, and human rights should not “be used as a tool to pressure other countries and meddle in their internal affairs.” The “wolf warriors” are, therefore, intending to counteract the Western discourse, portraying China as a strong advocate of human rights that are more comprehensive, diverse and balanced, a leading adherent to an international order that is more just and equal, despite their bellicose style may undermine China’s image in some countries.

The Cold War ended with the dissolution of the Soviet bloc, and the Helsinki Accords in 1975 and its subsequent process have been credited to give human rights activists behind the Iron Curtain a moral weapon against communist regimes. Can one expect something similar to happen to China? Or will China, with its rise, reshape the international order which is now led by the US and criticized because of the unilateralism and interventionism of the US? In order to re-legitimize their human rights diplomacy, particularly in the eyes of those Asian and African countries, Western powers have to acknowledge the “simultaneous interpretive pluralism” of human rights and recognize the equal if not greater importance of economic and social rights and good governance. Until and unless doing so, it would be too assured to assume that the current notion of human rights and the international order would not be rewritten, perhaps in a way that the idea of “rights as trumps” would be replaced by one of “sovereignty as trumps”.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – China’s Wolf Warrior Propaganda Versus Western Criticism in the Xinjiang Cotton Crisis

- Opinion – Making Sense of China’s ‘Wolf Warrior’ Diplomacy

- Opinion – The Civilisation Narrative: China’s Grand Strategy to Rule the World

- Opinion – The Path Beyond Trump in US Human Rights Policies

- Opinion – Impacts and Restrictions to Human Rights During COVID-19

- Opinion – Human Rights Concerns as Somaliland Seeks International Recognition