This is a excerpt from Signature Pedagogies in International Relations. Get your free download of the book from E-International Relations.

It can be said that the dissertation (or honors thesis) reflects the culmination of undergraduate studies. It is an opportunity for the student to pursue an independent piece of research into a topic of their own choosing. It can also be a daunting prospect for students, as often they have not been involved in such a research project before. For the supervisor, it is a chance to foster new research and to pass on some of their own experiences and knowledge to students. As part of the signature pedagogy of International Relations (IR), the dissertation presents an intellectual challenge for students, in which they have the opportunity to create new knowledge. As a dissertation supervisor at a number of British universities since 2006, the author has accumulated great experiences of the dissertation process. In this chapter, anecdotal evidence will be used to set out good practice in the supervision of dissertations in IR. Anecdotes are stories with a purpose, and they often reflect real-life incidents or examples. Aronson (2003, 1346) writes, “Anecdotal reports… should be published… a fact that is not emphasized by the evidence hierarchy.” Anecdotes can elucidate good practice, they can demonstrate teaching techniques, and they can provide testimony of pedagogical experiences. A novel strategy based upon establishing a two-way interactive dialogue with the student will be presented. The signature pedagogy of International Relations involves, mass lectures, small tutorials, and private study. Mass lectures, due to their sheer size, tend to limit student participation and interaction and can therefore lead to passive learning” (Harris 2012, 176). The dissertation therefore presents an opportunity for the student to become research-active, to engage in critical thinking, and it is, “preparation for ‘good work’” (Shulman 2005, 53). This chapter will set out what a dissertation involves, offer a strategy for supervision, suggest ways to encourage originality, and offer some conclusions. According to Todd et al. (2006, 163), “Most literature relating to dissertation supervision is aimed at masters and doctoral level students,” and this chapter aims to fill the gap in relation to undergraduate dissertations involving IR.

There are several differences between undergraduate and postgraduate dissertations in terms of length/word count, depth of analysis, length of literature review, methods of data collection, and purpose of study. Usually, undergraduate dissertations are shorter in length and tend to be more general or broader in scope, while postgraduate dissertations are more focused, more advanced, and more detailed on a given topic. The undergraduate dissertation introduces the student to the idea of research projects and promotes the signature pedagogy of IR, whereas postgraduate dissertations demonstrate some advancement in scholarship that can fill a gap in the knowledge of IR. Ergo, a postgraduate dissertation can contribute to ongoing research and identify openings for future research. This chapter aims to offer some insights into the supervision of undergraduate dissertations and thus focuses on how to introduce the idea of a dissertation to students rather than on experimental issues that involve postgraduate studies.

What the Dissertation Involves

The undergraduate dissertation usually happens in the final year of studies in the third or fourth year; in Scotland this means in the fourth year of undergraduate studies and, in the rest of the UK, it normally means in third year, though at some universities, like the University of Bath, it can also mean in the fourth year. It is part of the signature pedagogy of IR in which students “engage critically with a body of knowledge. This engagement facilitates understanding of key concepts and theories, and also provides students with the methodologies to analyze material” (Harris 2012, 176) and to apply this in practical terms. This involves the student picking a research topic and then carrying out research under the supervision of a lecturer or tutor. The dissertation is regarded as a course module, though there are no lectures[1] or tutorials throughout the term(s), unlike other modules. Each university department has its own regulations regarding the dissertation, and this usually involves the length of the dissertation (usually involving between 10,000 and 12,000 words with a 10 percent upper or lower threshold), the time period involved, an ethics procedure, formatting of the dissertation, deadline details, general regulations about the dissertation, and means of assessment. Some universities prescribe a formal process in which various elements of the dissertation study are set out with deadlines (e.g., submission of a literature review).

The dissertation is an independent research project carried out by the student under supervision. The purpose of the dissertation is to encourage the student to pursue research into a subject of their own choosing, in which they can demonstrate a range of research skills, show their analytical skills, interpret relevant information, and present their knowledge of the subject by writing up results in a logical and coherent manner. It also develops a range of practical skills and abilities, including time management skills, writing and editing abilities, negotiations (with supervisors and possibly interviewees), organizational skills, and to put into practice what they have learned during their degree studies. The dissertation is also a part of the peroration of the signature pedagogy of IR at undergraduate level. The dissertation becomes an opportunity for students to study a topic in more depth than they may have encountered previously in their studies. Importantly, the dissertation fosters critical thinking by the student themselves. Greenbank and Penketh (2009, 463) write that the dissertation “provides the vehicle for students to engage with their own thinking”. Moreover, the dissertation allows the student to take responsibility for their own learning; students have to think, plan, act, and reflect upon their work in order to learn and earn a good grade (Gibbs and Habeshaw 2011, 34-35). Producing a good dissertation can be satisfying for the student (and the supervisor), but it could also be cited in job applications or in postgraduate applications following graduation.

The dissertation is an assessed piece of work that contributes towards the final degree classification. In British universities, the norm is that the supervisor is the first marker, and there is a second marker, whose identity is usually unknown to the student. Sometimes a third marker might be called in or the external examiner gets involved where there are significant disputes by the markers. As the supervisor is also (usually) the first marker, this means that they cannot see the entire dissertation before its submission. Normal regulations are that the supervisor can read 1–3 draft chapters (or 30 percent) before submission, and this normally includes the introduction; in practice, the supervisor will have a good idea about what the dissertation is likely to look like. The assessment follows the usual departmental assessment scale, whatever that is. However, two key points about the assessment of dissertations should be made here. Firstly, the unique nature of the dissertation means that markers take assessment particularly seriously as they agree what the grade should be. Secondly, in final exam board meetings at the end of the year, the dissertation grade is (often) given added weight especially when a student is on the borderline between degree classifications. The author has attended many exam boards when the question is asked, “what did they get for their dissertation?” A good dissertation grade can therefore help the student improve their final degree classification.

A Strategy for Supervision

There is no right way to supervise a dissertation student, as each supervisor has their own different experiences of being supervised themselves. The convenor of the dissertation module has overall responsibility for dissertations, and they try to match supervisors with students as best as possible or allow students to find their own supervisors within their department. Once the student has a supervisor, the dissertation process begins. The strategy for supervision involves establishing a two-way dialogue with the student beginning at the first meeting. The first meeting should set the tone for the supervision process and establish a collegial working relationship between student and supervisor.

In my experience, the first meeting with the student is important as several outcomes should be achieved. For the student, they should have a better idea as to what the dissertation involves, they should have some initial work to do, and they should feel reassured that their supervisor is going to be helpful in their efforts. For the supervisor, they should know what the student wants to look at and why, they should pass on relevant information to the student, and they should establish a working relationship with the student. The first meeting should be as friendly as possible and the student should discuss the dissertation idea as much as possible. Supervisors should take notes throughout each meeting with students. As part of the signature pedagogy of dissertations, students, “are expected to participate actively in the discussions, rounds, or constructions; they are also expected to make relevant contributions that respond directly to previous exchanges” (Shulman 2005, 57). As preparation for this meeting, the author has developed a simple hand-out (or checklist) to show based on experience to explain to the student. This involves five points:

- What is the topic?

- What is the most appropriate theory?

- Structure of the dissertation

- Research issues

- Presentation of the dissertation

Each point is explained to the student beginning with “what is the topic?” Todd et al. (2006, 167) write, “The first major task, which the dissertation supervisor undertakes is to provide support for students in identifying and defining the research question”. It is important that the student explains what it is they want to study and why they want to study the topic. Sometimes the student does not have a topic and, in such cases, a discussion about the subjects in which they are interested should elicit a potential topic. Roselle and Spray (2012, 6) write, “Choosing a topic is often the most difficult component of writing a research project”. Where students are involved in a joint degree, the other discipline should be incorporated into the dissertation, where possible. In IR, the topic could be contemporary, historical, theoretical, policy-related, or thematic; this also applies to other social sciences and, perhaps especially, politics. The student does not necessarily need an actual question at this stage, but they should be asked to develop a hypothesis (or several related hypotheses) to help generate a question or proposition; this will also help develop the eventual title of the dissertation. The hypothesis will also encourage the student to think more coherently and critically about the topic.

Anecdote 1: The author usually asks students to pick a topic in which they are interested as this helps their motivation OR choose a subject about which they know little/nothing, and this becomes a motivation for the study. As students are researching in an autonomous manner with no set timetable, self-motivation becomes an important factor.

The second point is to ensure that the student incorporates an appropriate theory or concept(s) into the study. Matching a theory to a topic is a central part of achieving a good grade for the dissertation in IR. This is a point that the supervisor should convey to the student as early as possible. Sutch and Elias (2007, 4) write, “IR theory is basic to the study of world politics… IR theory attempts to elaborate general principles that can help orientate us in our encounter with the complexities of world politics”. By the time students are considering their dissertations, they should already have completed a module(s) on IR theory; this is an important part of the signature pedagogy of IR. By incorporating IR theory into the dissertation, the student can demonstrate their theoretical knowledge in a practical manner. It is incumbent on the supervisor to ensure that the student recognizes the need to incorporate a theoretical or conceptual dimension into the study. As signature pedagogies involve, “defin[ing] how knowledge is analyzed, criticized, accepted, or discarded” (Shulman 2005, 54), the inclusion of IR theory into the dissertation becomes important as part of this process. The dissertation should include a golden thread of theory, meaning that each chapter should have some theoretical component. The integration of theory into the dissertation is part of the vocabulary of IR, and it “also provides possibilities for students’ emancipation” (Marsden and Savigny 2012, 128). The theoretical element also contributes towards the originality of the dissertation and demonstrates the implicit structure (Shulman, 2005, 55) of IR as an academic discipline. The inclusion of theory in the dissertation also symbolizes that the student is actively learning and is being socialized into having the mind-set of an IR thinker.

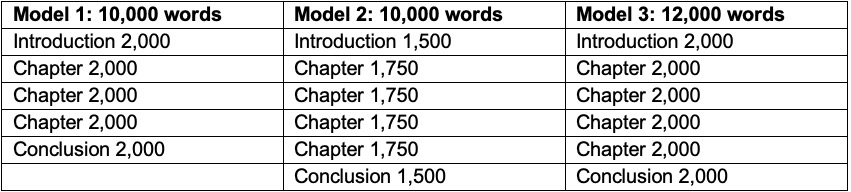

The third point concerns the structure of the dissertation. This relates to the number of chapters, the order of chapters, and the word count for each chapter. Usually, departmental regulations will stipulate that dissertations have a title page, an abstract, contents page, chapters, bibliography, and appendices. Appendices[2] are not usually included as part of the word count. If the dissertation is 10,000 words long, then there are, broadly, two structural models to recommend to students. The first is a simple five-chapter dissertation with approximately 2,000 words assigned to each chapter. This should include an introduction, three substantial chapters, and a conclusion. This provides scope for a methods/theoretical/historical background chapter and two case studies. The second involves a six-chapter dissertation involving an introduction of 1,500 words, four chapters of 1,750 words each and a conclusion of 1,500 words. A 12,000-word dissertation would follow a similar format.

The contents of each chapter differ from dissertation to dissertation, but the student should follow some structure as this will help form a clearer focus for each chapter and help them to keep to the word count as much as possible.

The fourth part of the discussion is about research issues. Many students will have taken a research methods module in their studies by the time they begin their dissertation. The supervisor should explain (or remind students) to carry out a literature review, and to consider carefully what research method(s) to consider. Roselle and Spray (2012, 5) write, “Political scientists must build on the research of others”. Todd et al. (2006, 167) write, “The supervisor’s role is also to ensure that what the student intends to do is feasible in scope and sensible in terms of ethics”. Methods could be qualitative, quantitative, or a mixture of methods. A range of methods or approaches should be discussed at this point with the student. In some ways, this reflects the surface structure (Shulman 2005, 54–55) of the signature pedagogy of supervising IR dissertations. Sources of information, such as the university library, online sources, journals, broadcast media, print media, and official documentation, should be identified to the student to consider utilizing.

Depending on the dissertation topic, other sources of information could be discussed, such as films, departmental research seminars, and sitting in on lectures (from their department or other university departments where appropriate). If the student considers interviews, then the supervisor should set out some of the practical aspects of this (e.g., setting up meetings, recording, etc.) (Todd et al. 2006, 168). In addition, all universities now have an “ethics policy,” and this should be explained to the student. At some point during this initial meeting, the author usually tells the student that they should consider themselves as being “a researcher” and not “a student”; for some students, this becomes a gateway into thinking about postgraduate education. This should help establish a working relationship which, in turn, should facilitate a two-way dialogue. It is important that the views of the student are aired during this meeting and at subsequent meetings, as they are the one working on the study; the student should be active and not passive throughout the dissertation process. Time management should also be discussed; 5–8 hours per week minimum should be scheduled into the student’s timetable for dissertation work.

The final point relates to the presentation of the dissertation. This includes some discussion about technical issues, such as font size, the use of maps or diagrams, what the title page should look like (sometimes it can include the title, author, and year, but sometimes it can include a picture/image), using margins,[3] and including page numbers. It is useful for the supervisor to show old dissertations to the student as examples; good and bad. Showing the student “the final product” is helpful so that the student has a better idea of what they should aim towards; many students have said to the author that this was helpful. The referencing system should also be discussed; whether using footnotes or the Harvard system.[4] The regulations for the dissertation might dictate which referencing system is used. The author has suggested to students that each chapter could begin with a short quote as a means to introduce each chapter. Some students like this, while others do not, but it is an interesting thing to mention.

Anecdote 2: The author prints out this five-point checklist for students at the first meeting. At the end of term, one student told me that he carried the note with him throughout the term and used it to add notes and comments, and to remind him to work on the dissertation.

When this first meeting is ending, the supervisor should ask the students if they have questions. The supervisor should also agree some schedule for future meetings, exchange e-mail details, and ensure that both parties know what is happening. It is advised that students should try to have at least one face-to-face meeting once a month throughout the term(s) and maintain e-mail contact; the use of social media such as Facebook or Twitter is also useful to maintain contact. Woolhouse (2010, 137) writes, “Much of what happens between tutors and students is ‘semi-public’.” By engaging with the student throughout, a two-way dialogue should identify any problems, facilitate good research by the student, and be pedagogically rewarding for student and supervisor. In subsequent meetings, the student should report what they have done and what they are going to do. Supervisors should ask questions, provide feedback, and offer appropriate advice at each meeting in a collegial manner.

Encouraging Originality

To an extent, all dissertations are original as students write in their own way, include their own analysis, and present their own findings. Gill and Dolan (2015, 11) write, “The concept of originality is commonly associated with something truly novel or unique.” However, in IR, over the past decade or so, there have been a number of popular topics relating to 9/11, EU politics, US foreign policy, the rise of China, and the financial crisis of 2008. Originality is important (and better grades usually follow), and it evinces the student as a knowledge creator. The supervisor should encourage as much originality as possible in terms of subject matter, use of theory, research, and reading. Originality can be discerned in a number of ways: if the topic is new, if a new theory is being used, if the research involves the gathering of new information, if new interpretations are offered on an old topic, or if a new concept or idea emerges from the study (Gill and Dolan 2015, 12).

There are various ways in which a supervisor can encourage originality, and this is done in conjunction with the student. By incorporating different layers or components into the dissertation, originality can be developed. For example, one student wanted to explore the intelligence capabilities of small states. A discussion was held in which possible case studies were mentioned, theories were suggested, and some practical issues were raised. It was agreed that a comparison between Israeli and Cuban intelligence would be feasible partly because of the amount of literature on each case. It was suggested that game theory might be an interesting approach as the student had not looked at this before, and the student was able to interview another member of staff whose main research involved Cuba. During the research, the student also identified “prospect theory” (a theory of economic behavior), and this was incorporated into the analysis. In addition, small state perspectives added another dimension to the study. These various components (theories, comparative case studies, qualitative research, and literature review) cumulatively created an original piece of dissertation research. Throughout the term, the student consulted the supervisor, and an ongoing exchange of ideas were expressed.

Anecdote 3: At one university I was asked to supervise a dissertation on “reform of the UN Security Council” (an important and interesting topic). The following year, I was asked to do this again. On the second occasion, the student involved was from Ireland, and I suggested a slight variation: what is the Irish position about UN Security Council reform? This would have been a (slightly) more original topic at a British university.

A second example involves a student who wanted to study the problem of Somali piracy off the East coast of Africa. The subject was both topical and important. The Copenhagen School approach, and especially the “five types of security” (Buzan 1991) was suggested as a theoretical lens for the study; this also helped the structure of the dissertation. The student identified a law lecturer in another university, who was an expert in maritime law, and a group of Somalis living in the area. The student was able to carry out interviews with the expert and a Somali person, which focused on the piracy issue. The combination of original interviews, literature, theory, and a focus on the piracy issue resulted in an original piece of research. Again, these different elements combined to create an interesting and original dissertation.

A third example in which originality was found came through an initial discussion about the dissertation. The student wanted to explore the concept of “soft power” as expressed by Joseph Nye (2004) in IR. The student had carried out a brief literature search and, in this discussion, mentioned the Jimmy Carter Library (https://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/). As supervisor, the author asked if this was possibly a source of US soft power. The student used this idea in the subsequent research, which included two interviews using Skype. In an extended literature review, the student found that no one had ever written about US Presidential foundations as a source of US soft power before; this constituted an original piece of research. The two-way dialogue between supervisor and student can encourage original thinking and original research outcomes.[5]

Anecdote 4: One student was studying the accountability of British intelligence agencies and he wanted to carry out an interview(s). The nature of the topic meant this was problematic, but the author suggested that a possible interviewee could be the local MP. An interview was carried out and this was both informative and original. While an MP might not be an “expert,” they will have opinions that can be of interest.

Conclusions

Researching and writing a dissertation is a form of active learning that transforms the student from a consumer of knowledge to a creator of knowledge. It also demonstrates that the student follows a signature pedagogy of IR. The supervisor, in this context, becomes a conduit to this learning process. Supervising involves imparting knowledge and instilling the student into the culture of IR as an academic discipline. In crude terms, supervision is somewhat akin to an indoctrination process. By creating a two-way dialogue and acting in a collegial way, the supervisor can encourage good research by the student. The supervision process involves a surface structure in which the supervisor sets out many aspects of the dissertation, a deep structure in which thinking like an IR scholar is encouraged, and an implicit structure in which the attitudes and dispositions of IR are imparted to the student (Shulman 2005). The student should be active and enthusiastic about the research, and should be as professional as possible. Using anecdotes based on personal experiences throughout this chapter, highlights good practices and how a dialogue with the student can foster originality in undergraduate dissertations involving IR. The efficacy of good supervision following the signature pedagogy of IR becomes a rite of passage for the undergraduate. Moreover, the inclusion of appropriate IR theories coupled with original research, such as interviews, can foster better (and more interesting) dissertations. Supervising undergraduate dissertations can also be pedagogically and intellectually rewarding for the supervisor, especially when the students get good grades as a result.

Figures and Tables

Notes

[1] There is usually one introductory lecture to review and explain the dissertation process and to encourage students to begin thinking about the dissertation topic at the start of the process.

[2] Appendices are useful ways to add information, such as interview transcripts, maps and diagrams, evidence of ethics, and other additional information.

[3] As a supervisor, I usually ask students to “justify” the text instead of “left align,” as the end product looks better, but this is subject to university regulations.

[4] The author always advises student to begin a running bibliography for the dissertation partly as good practice, partly to ensure they adopt a systematic approach to the dissertation, but largely to avoid problems when finishing writing up the study.

[5] In each of these three examples, the dissertations each got a first in their grade.

References

Aronson, Jeffrey K. 2003. “Editorials: Anecdotes as Evidence” British Medical Journal (BMJ) 326, 1346.

Buzan, Barry. 1991 edition. People, States and Fears Hemel Hempstead, Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Gibbs, Graham and Habeshaw, Trevor. 2011. “Preparing to Teach.”Creative Commons. Accessed July 2020. https://creativecommons.org/

Gill, P. and Dolan G. 2015. “Originality and the PhD: What Is It and How Can it be Demonstrated?” Nurse Researcher 22:6, 11–15.

Greenbank, Paul and Penketh, Claire. 2009. “Student Autonomy and Reflections and Writing the Undergraduate Dissertation” Journal of Further and Higher Education 33:4, 463–472.

Harris, Clodagh. 2012. “Expanding Political Science’s Signature Pedagogy: The Case for Service Learning” European Political Science 11, 175–185.

Jimmy Carter Library 2020. Accessed July 2020. https://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/.

Marsden, Lee and Savigny, Heather. 2012. “The Importance of Being Theoretical: Analyzing Contemporary Politics” in Teaching Politics and International Relations, edited by Cathy Gormley-Heenan and Simon Lightfoot, 123–131, Basingstoke, Palgrave.

Nye, Joseph. 2004. Soft Power New York, Public Affairs.

Shulman, Lee S. 2005. “Signature Pedagogies in the Professions” Dædalus 134 (Summer), 52–59.

Sutch, Peter and Elias, Juanita. 2007. International Relations: The Basics, London and New York, Routledge.

Todd, Malcolm J., Smith, Karen and Bannister, Phil. 2006. “Supervising a Social Science Undergraduate Dissertation: Staff Experiences and Perceptions” Teaching in Higher Education 11:2, 161–173.

Roulston, Carmel. 2012. “Supervising a Doctoral Student” in Teaching Politics and International Relations, edited by Cathy Gormley-Heenan and Simon Lightfoot, 210–225, Basingstoke, Palgrave.

Woolhouse, Marian. 2010. “Supervising Dissertation Projects: Expectations of Supervisors and Students” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 39:2, 137–144.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Use of Metaphors, Simulations, and Games to Teach International Relations

- Student Led Advocacy and the ‘Scholars in Prison’ Project

- Teaching International Relations Through Short Iterated Simulations

- Teaching and Learning Professional Skills Through Simulations

- Signature Pedagogies and the Use of Violence in In-Class Simulations

- Marks That Matter: Slow Letters to Authors and Selves