The sectarian wave that has swept over the Middle East and North Africa since the Arab Uprisings has profoundly reshaped regional politics. Syria has become an epicentre of sectarian conflict that has drawn in sectarian actors from without and spilled out over the region. It is therefore a sort of laboratory in which we can explore the dynamics of sectarianism in the region. Understanding the Syrian case requires some engagement with the theoretical debates on sectarianization. The main debate is: to what extent does sectarian identity determine political interests, strategies, alignments and conflicts and to what extent is sectarianization an outcome of these factors? The polar master narratives are the “primordialist,” which sees identity determining politics, and the “instrumentalist,” which sees politics using identity: in their cartoonish form, they could be called the “ancient hatreds” vs. the “evil authoritarian leaders” approaches. Primordialists regard sectarian conflict as the natural and inevitable consequence of the juxtaposition of long-standing religious differences, while instrumentalists see it as the product of political strategies by regimes and opposition movements. These polar opposites provide a starting point, but neither alone has sufficient explanatory capacity; and how far each shapes outcomes depends on other intervening variables. This article will first outline a framework of analysis that identifies the key variables and their inter-relations; then, the framework will be applied to analyze the Syrian case.

A framework of analysis for understanding sectarianization

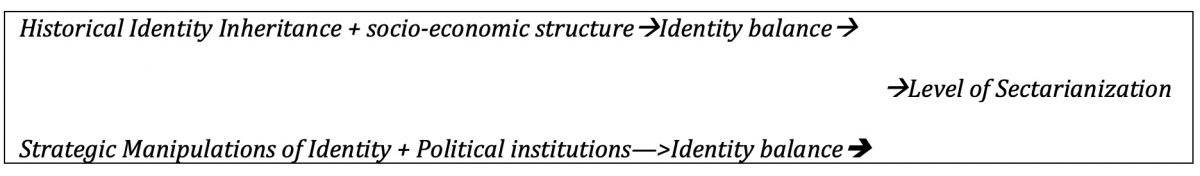

The dependent variable, that which we seek to explain, is the level of sectarianization at a particular time and place, including its saliency in political agendas and its intensity (ranging from mild non-politicized—banal forms of sectarian identity to militant politicized forms that deny legitimacy to other sects). This is most immediately a function of the power of alternative identities relative to sectarian ones (the “identity balance”). Two independent variables and intervening variables help explain this dependent variable.

Independent variable I

The historical identity inheritance includes the distribution of sectarian groups: thus, concentrations of compact minorities in particular regions or the arrival of incoming sectarian “Others” in communities with homogenous sectarian affiliation are likely to increase sectarian consciousness. However, whether this happens depends on other factors such as historic memories of amity or enmity among sects and how far sectarian identities have been historically politicized. This, in turn, is likely to be affected by how robust alternative identities are. These can be either more inclusive, and hence may subsume sect, such as Arab nationalism, or can dilute it by cross-cutting and dividing sectarian groups, as when the latter are divided by class (see below on intervening variables).

Independent variable II

Political actors’ strategic manipulations of identity whether political entrepreneurs believe it serves their interests to instrumentalize sectarianism or some rival identity will be as decisive as the identity inheritance in determining outcomes. These political actors—possible “sectarian entrepreneurs”—are located at three levels: at the state level (regime and opposition actors); at the trans-state level (social movements, prominent religious leaders and media activists); and at the international level (e.g. rival outside powers using sectarianization to foster proxies in the Syrian conflict). The designation of both the historical inheritance and strategic manipulation of identity as independent variables is because both have to be present before sectarianization occurs; if only one is present there will be no sectarianization.

Intervening variables

Several “material” factors also affect the balance among identities (their saliency and intensity), as well as whether they are likely to be instrumentalized. The interaction of these variables is summarized in figure 1.

- Socio-economic structure: this includes the impact on identitiesof levels of modernization(literacy, education levels) which may either generate broader identities (e.g. to the state or nation) diluting sectarianism or, alternatively, subsume smaller identities (e.g. tribe) in sectarian ones, thus increasing sectarian saliency. Second, it includes the impact of class cleavages, which may either cross-cut and dilute sectarian differences or overlap with and reinforce them.

- Political Institutions: this variable has two dimensions. First, the stability of political order matters, that is, whether security is maintained. If security breaks down, unleashing levels of violence and consequent feelings of high insecurity, sectarian solidarity and enmity toward the sectarian “other” increases. Second, the inclusiveness of political order, that is, the extent of incorporation—participation or co-optation—of groups and strata into state institutions matters: high inclusiveness tends to dilute sectarian identities and foster that with the state, while exclusion of certain sectarian groups drives sectarian consciousness and mobilization (for a more detailed explication of the framework see Hinnebusch 2018; Hinnebusch 2019).

Syria’s Sectarianization

Several factors established a favourable context for Syria’s sectarianization even before the uprising broke out, but they became much more powerful as a result of it (Hinnebusch and Rifai 2017). Sunnis make up 74% of Syria’s population and Alawis about 12%. The latter are however greatly overrepresented in Syria’s ruling regime, with the president and many top security and military commanders from this sect (see Lust 2014, p 767.) The Identity Inheritance; the distribution of demographic groups—e.g. the Sunni majority vs. the Alawi minority—had not significantly altered over the decades, so why did it come to matter so much after 2011? There is no escaping the fact that the strongest regime loyalists were Alawis and, to a lesser degree, other minorities, and that the vast majority of the protests were in Sunni neighbourhoods. There had been some incremental demographic alteration. Notably, the out migration of the Alawi minority was seen by Sunnis in places such as Homs and the Damascus suburbs to be intruding on their communities and opportunities. However, this was a very incremental process and had not been hitherto associated with much overt sectarianism. More important were alterations in the identity balance that weakened alternative identities that had diluted sectarian ones.

Pre-Uprising Intervening variables were arguably responsible for this. On the one hand, while class identities had long diluted sectarian ones, they started to reinforce each other in the decade before the uprising. Until 2000, the incorporation of significant rural Sunnis into the regime, via land reform and populist policies, had split Sunnis between such beneficiaries of the regime and its opponents (the old Sunni landed and merchant classes), a factor that explained the failure of the Muslim Brotherhood uprising of the early 1980s (Hinnebusch 2011, 47-88, 93-103). Under the neo-liberal policies followed after 2000, however, the Ba’th Party’s rural constituency was neglected, while Alawis were the most salient beneficiaries of the emerging crony capitalism—although considerable numbers of the Sunni business class remained aligned with the regime, which helps explain its resilience. Overall, though, class identities were coming to reinforce more than cross-cut sectarianism.

In parallel, the ruling party that had incorporated the regime’s constituencies was withering away, losing ideological coherence as both neo-liberal and Islamic attitudes penetrated it. In the succession struggle of 2000 that brought Bashar al-Asad to power, many of the senior Sunni lieutenants of Hafiz al Asad were purged, and with them the regime, losing important Sunni clientele networks, became less inclusive. Thus, the regime was becoming both more Alawi and more upper class, and less inclusive of the rural majority, a scenario for inflaming sectarian identities among those who suffered from these developments.

In short, institutional inclusiveness, thus identification with the state, was declining among many ordinary people. While the regime continued to enjoy some legitimacy from its instrumentalization of Arab nationalism, notably defying the US in its invasion of Iraq, Arabism’s historic power to dilute sectarianism was in precipitous decline and proved insufficient to immunize the regime against the Uprising, as Bashar al-Asad mistakenly believed (Hinnebusch 2012, 2015; Matar 2016, 13-35).

The Syrian Regime’s rhetoric vis-à-vis the Uprising: playing with sectarian fire?

As the uprising broke out, the rival sides began to instrumentalize sectarianism. It is true that the first slogan of the Syrian uprising was al sha’eb al sourry wahed (the Syrian People are one), an appeal to a cross-sectarian Syrian identity. The anti-regime protestors understood that only united did they have a chance to force a political transition and that the regime would try to divide them. Nonetheless, a decade of war proved that they were not “one.” What started as a peaceful movement for social justice and freedom morphed into a bloody war in which sectarian identities were instrumentalized by discourse from above and from below, inflaming identity clashes.

The regime bore major responsibility for this. The two strategies that were applied by the regime to quell the uprising relied upon asabiyya (communal solidarity), which reinforced Alawite identity. These two strategies were al-hal al-‘amny (the security solution) and al-hal al-a’askary (the military solution). The security solution denotes the deployment of loyal security forces, heavily Alawi, against protestors, as well as al- lijan al- sh’abiyya (popular committees), and shabiyyaha. Shabiyyha refers to the pro-Assad militias that consisted predominantly of Alawites whose main mission was to punish anti-Assad activists, the majority of whom are Sunnis (Rifai 2014; Rifai 2108). With the eruption of the uprising, these loyalist forces frequently besieged mosques that were primary sites for anti-Assad protests, mainly in Sunni districts (Rifai 2014). Notably, forces loyal to the regime often displayed identifiers of their communal belongings, such as the Zulfiqar sword. A sword with two blades that the Islamic Prophet Mohamed gave to his cousin Ali bin Abi Talib, this sword is an important holy symbol for Alawites and Shiites. Such symbolic features acted as signifiers of Alawite identity and emphasized the sectarian line between ‘us’ and ‘them’. (Rifai 2018)

In February 2012, the regime applied the military solution that involved a nationwide deployment of the Syrian army and heavy shelling of rebel areas. Suburbs of Damascus and Homs were among the first regions to experience the military solution. Regime forces established their bases in Alawite areas and started to target Sunni neighbourhoods. Lootings, kidnappings, and torturing incidents took place within a chaotic context of a security dilemma (Rifai 2018). By deploying Alawite–dominated forces, the Syrian regime projected the image of the uprising as a sectarian conflict threatening to all Alawis, making them feel that they were fighting for their survival. On the other hand, discourse by many anti-Assad Sunnis (opposition figures and even ordinary protesters), among whom regime violence had inflamed Sunni sectarian solidarity, verified the claims of the regime. Therefore, many Alawites could not perceive any alternative way of surviving other than to fight for the regime, and for many Sunnis, to fight against it (see Rifai 2018).

Regional Powers in the reconstruction of sectarian identities

Before long, Iran and Hezbollah, on the one hand, and Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar, on the other, instrumentalized sectarian identities in their regional power struggle, which came to be focused on Syria, thereby aggravating identity clashes in the region and in Syria in particular (Phillips 2015). From early on, Iran and Hezbollah had been intimately involved in supplying the Assad regime with political and military support to ensure its survival. As Mehdi Taeb, a senior Iranian cleric, put it when speaking about Iranian stances in the Syrian wars: ‘Syria is the 35th province [of Iran] and a strategic province for us. If the enemy attacks us and wants to take either Syria or Khuzestan [Western Iran], the priority for us is to keep Syria. If we keep Syria, we can get Khuzestan back too; but if we lose Syria, we cannot keep Tehran’ (Ya Libnan 2013).

On the other hand, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey sponsored proxies from the Sunni community, notably Muslim Brotherhood militias by Qatar and Turkey and salafists by Saudi Arabia; but also Qatar and Turkey at times flirted with Salafi jihadists such as al-Qaida avatars, Jabhat al-Nusra and Islamic State (Phillips 2016). These regional powers, especially Saudi Arabia, portrayed the conflict as part of a broader struggle to defend Sunnis against the Shiite axis in the region. Turkey’s rhetoric, its allowing of Jihadists to infiltrate into Northern Syria, and funding of militias in Idlib, while also deploying Syrians to fight in Azerbaijan and Libya under an Islamic banner −these all also helped in reproducing a particular version of Sunni identity that would serve Turkish President Erdogan’s interests. For instance, he frequently cited the Muslim’s holy book, emphasized Ottoman history and declared that rebels in Northern Syria were members of the Army of prophet Mohamed (Rikar 2019).

Sectarianization from above propelled a similar process from below. Inflammatory sectarian rhetoric flooded social media and satellite TV, much of it by Arab Gulf-based preachers (Philips 2016). Hezbollah and Iranian forces fighting in sectarian mixed areas, notably in the suburbs of Homs, fuelled sectarian clashes. Hezbollah fighters waved yellow flags and wore green headband (symbols of Shiites) while Sunni rebels waved the white and green flag and wore black headbands (Rifai 2014). This made identity clashes and the reproduction of sectarian identities very visible. Pictures of killed Shiite soldiers are seen alongside a religious quotation from Imam Ali (the most important Shiite figure) in Homs and in the heart of Damascus. Turkey’s approach also interacted with discourse from below, where many Syrians in Idlib waved Turkish flags alongside the white and green Salafi ones. Rebels named militias after Ottoman Sultans, and some cafés in Idlib were even named after Erdogan.

Thus, the political and military support given by the opposing external powers heightened the sectarian narrative and instigated identity clashes among Syrians. The main objective of these actors was to survive and prevail in the regional power struggle–the drivers of their behaviour being political interests, not sectarian enmity and amity (Phillips 2016). However, given their sectarian identity and discourses, their intervention was perceived in sectarian terms and henceforth inflamed the sectarianization of the conflict.

Intervening variables: the impact of geography and social stratum

One common generalization about the war in Syria is ‘Sunnis are in a power struggle against the Alawites’. However, while some of them are, others are not. Whether actors, particularly Sunnis, saw the struggle as a sectarian one between Sunnis and Alawis depended, to a considerable extent, on the neighbourhood they came from and the social class they belonged to. Thus, in the centre of Damascus, both the regime and the Damascene Sunni elite attempted to protect the status quo during the war. Sectarian militias and popular committees were not allowed in upper and upper-middle-class areas such as Malki, Abu Rummaneh, Rawda, Kafrsouseh, and some parts of Mazzeh. By contrast, Barzeh, a Ghouta town (or suburb) in northeast Damascus inhabited by lower strata, was among the first areas to host anti-Assad protests and to be targeted by regime forces, mostly residents in neighbouring ‘esh al warwar, (inhabited mainly by Alawite military families) (Rifai 2014). Therefore, the formation of sectarian identities during the conflict is not a simple process and alters according to time and interests, with identities most durable when congruent with interests and weaker when incongruent.

How instrumentalization of sectarianism “fed back” on and altered Syria’s identity balance: The power struggle between Islamism and Syrianism

Prior to the uprising, the identity balance that Hafiz Assad carefully crafted was composed of Arabism as an umbrella identity supposed to subsume sectarian identities and overlapping with and assimilating some content from Syrianism and Islamism (Rifai 2014). Yet, this balance was strongly shaken after the outbreak of the uprising. Arabism declined and even seemed to be fading especially after the suspension of Syria’s membership in the Arab League in November 2011 (Rifai 2014). For the Assad regime, what were long considered sister Arab States were now enemies, supporting its opponents and seeking to change the regime. The Assad regime had instrumentalized Arabism for four decades because it served its interests; post 2011 reality would force the regime to instrumentalize different identities, notably Syrianism (Rifai 2014). Many pro Assad Syrians believed that the Arab States betrayed Syria. Even for the anti-Assad Syrians, support by the Arab States was not sufficient and came to believe that the Arab world had ‘let them down’: a popular song among protesters in 2011-2012 was called ya Aarab khazlutna (Oh Arabs you failed us). Henceforth, what Chris Phillips (2013) termed ‘everyday Arabism’ seems to be declining in Syria due to everyday sectarianism.

While, as has been seen, both regime and opposition deployed sectarianism to mobilize core supporters, only more inclusive identities had a chance to unify large numbers of Syrians. However, the rival Syrian actors promoted differing substitute identities. On the one hand, sectarianization had empowered Islamism at the expense of Arabism especially among the Sunni masses. But different versions of Islamic identity were being reproduced in different places and among different groups in Syria. While the “moderate” Sufi oriented version of Sunni Islam that the regime had promoted prior to the conflict was fairly inclusive, it was challenged by more fundamentlist Salafi versions of Sunni identity, and even more radical Jihadi versions of Salafism were used to mobilize armed anti-regime fighters (Rifai 2014).

Conversely, Syrian national identity was being reproduced as an inclusive identity for secular and non-Muslim Syrians. The Syrian regime sought to empower Syrian identity, emphasizing Syria’s distinct history and Aramaic language, and even creating a new curriculum that recalled Syrian national figures and stressed the glory of Syrian history. This might sound surreal for Syrians of the older generation who grew up chanting slogans like one Arab nation and who for long identified themselves as Arabs born in Syria, the beating heart of Arabism. The secular opposition was also seeking to reproduce a Syrian national identity. A myriad of charitable networks, political movements, and communication tools adopted national names like “My Syria” and “Syrians across borders,” denouncing sectarianism and seeking to unite Syrians (Rifai 2014). Hence, Islamism and Syrianism seemed to be in a struggle to dominate, as different actors sought hegemony via different legitimating ideologies. If the more inclusive identities, Syrianism or moderate Sufi Islam, win out, sectarianism may be diluted by being subsumed in such broader identities. Differently, Jihadi Islam overlaps with Sunni sectarianism and tends to provoke, in turn, a sort of “anti-takfiri” sectarian identity among some Syrian minorities. If this trajectory prevails and permeates Syria’s identity heritage, co-existence will become harder than ever (Rifai 2014).

Returning to the framework of analysis: lessons from the case

How can we summarize what the empirical data tells us about why Syria experienced high levels of sectarianization in the course of the Uprising? Syria’s inherited identity pattern had kept sectarian consciousness alive, albeit suppressed by the dominant Arab nationalist discourse—thus, remaining banal or, for Alawis, instrumentalized as wasta (clientele connections). For sectarianism to become not only salient but also militant and intolerant of the “Other,” many things had to go very wrong.

Importantly, the post-2000 greater Alaw-ization of the regime ruling core and the reconfiguration of the regime’s social base to embrace crony capitalists while relatively neglecting its former Sunni peasant constituency, started to generate sectarian resentment among those suffering from this process. As the regime became less inclusive, the door was potentially opened for sectarian entrepreneurs to mobilize opposition among the Sunni underclasses. But it took agency for this to happen. On the one hand, the sectarian strategies the regime used to counter protestors, notably violence, implicated the Alawis in this repression, stimulating their sectarian solidarity and forcing them to remain loyalist. On the other hand, regime violence stimulated the growing use of Salafist Islam to mobilize opposition fighters. Furthermore, not just the fighters on both sides but also non-combatants were drawn into sectarianism by the insecurity unleashed through the breakdown of order under civil war. Each group sought protection by self-arming, sectarian cleansing, etc., which only enhanced the insecurity of all sides, not to mention the depth of enmity. The intervention of external powers—through arming, funding or providing fighters parallel to sectarian discourses—greatly aggravated sectarianism while also making a resolution of the conflict very difficult. A first condition for de-sectarianization is therefore the end to such external competitive intervention in Syria’s conflict. But ultimately what happens will be down to the agency of Syrians. In this regard, much will depend on what dominant national identity is constructed to replace (or restore) Arabism.

Figure 1: Framework of Analysis

References

Hinnebusch, Raymond (2011) Suriya: thawra min fauq [Syria: revolution from above], Beirut: Riad al-Rayyes Books.

Hinnebusch, Raymond (2012) “Syria: from Authoritarian Upgrading to Revolution?” International Affairs, January.

Hinnebusch, Raymond and Zintl, Tina (2015) “The Syrian Uprising and Bashar al-Asad’s First Decade in Power,” in Hinnebusch and Zintl, eds., Syria: From Reform to Revolt: volume 1: Politics and International relations, Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 285-310.

Hinnebusch, Raymond (2019) “Sectarianism and governance in Syria,” In Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism. 19, 1, p. 41-66. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/sena.12288

Hinnebusch, Raymond (2020) “Identity and State Formation in multi-sectarian societies: between nationalism and sectarianism and the case of Syria, Nations and Nationalism, January, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/nana.12582

Hinnebusch, Raymond and Rifai, Ola (2017) “Syria identity, state formation and citizenship” in N Butenschon and R. Meijer, eds. The Crisis of Citizenship in the Arab World Arab, Leiden: Brill.

Lust, Ellen (2014), The Middle East, Thousand Oaks, California: CQ Press.

Matar, Linda (2016) The Political Economy of Investment in Syria, Basingtoke, UK: Palgrave MacMillan

Phillips, Christopher (2013) Everyday Arab Identity: the daily production of the Arab world, Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Phillips, Christopher (2015) ‘Sectarianism and conflict in Syria.’ Third World Quarterly 36:2, pp. 357-376

Phillips, Christopher (2016) The Battle for Syria: International Rivalry in the New Middle East, New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Rifai, Ola (2014) The shifting balance of identity politics after the Syrian uprising | openDemocracy, April 28, Open Democracy website accessed on 3/26/2021

Rifai, Ola (2018) “The Sunni/Alawite identity clashes during the Syrian Uprising” in R, Hinnebusch and O. Imady, The Syrian uprising; domestic origins and early trajectory, Abingdon: Routledge.

Rikar, Hussein (2019) How Turkey’s Erdogan Portrayed Syria Offensive as a Pan-Islam Struggle | Voice of America – English (voanews.com), November 13, VOA News website accessed on 3/26/2021

Ya Libnan (2013) Iranian cleric: losing Syria is like losing Tehran on Iranian cleric: Losing Syria is like losing Tehran – Ya Libnan, February 16, ya Libnan website accessed on 3/26/2021.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Assad’s Regime Has Fallen: Time to Lift Sanctions on Syria

- Opinion – Post-Assad Syria’s Cautionary Tale

- Opinion – China and the Rebuilding of Syria

- Turkey’s Role in Syria: A Prototype of its Regional Policy in the Middle East

- The Limitations and Consequences of Remote Warfare in Syria

- Opinion – Recognizing Syria’s New Government Risks Middle East Stability