The year 2020 was a year of domestic lockdowns, enclosed international borders, dramatic retreats for global trade and tourism. A new breed of coronavirus discovered in Wuhan, China, swept across the globe, ushering in the broadest pandemic since 1918’s Influenza. Unexpected shockwaves affected domestic, as well as international, relations.The sudden arrival of COVID-19 provided a crash course for globalization. During the early months of pandemic, reliable data was scarce. That could have reinforced bonds of diffuse reciprocity cutting across states and communities. In hindsight – after more than 150 million cases and 3 million casualties – the international community would have greatly benefitted from a set of common rules, steered in indivisible and equanimous fashion by international public agencies. That proved not to be the case. As region and nation-based lockdowns were unilaterally instituted across the first semester of 2020, World Health Organization’s technical authority was in checkmate.

COVID-19 represented a lost opportunity for Multilateralism. As an overt lack of international leadership overlapped with autarchic policies in the course of pandemic, outcomes were mostly detrimental to multilateral cooperation (already in decline across the century). National decisions undermined collective responsibility and refrained from the ultimate goal (ceasing the spread of the disease). Additionally, leading multilateral agents performed sub-optimally across 2020. Under Donald Trump, the United States (a challenged superpower) abandoned Multilateralism, rendered a liability to “America Great Again” instead of a long-lasting asset of hegemony building. This empty seat left additional problems for the multilateral machinery. Plagued by lack of coordination, including member states (Italy, Spain) which were early pandemic epicenters, the European Union could do little to ameliorate international turbulence. The Schengen Zone was closed on grounds of national security, as member states provided economic aid and medical services acting on their own. In this context, the EU could hardly claim leadership in a global scale – even though its support to Multilateralism remained (at least rhetorically) unchanged.

China – where the pandemic begun in late 2019 – kept a low profile, apart from an ambivalent relationship with the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Even though its lockdown policies significantly reduced domestic levels of illness, China displayed recalcitrance in disclosing COVID-19 data and correlated policies to international audiences. Therefore, it could exert little soft power.

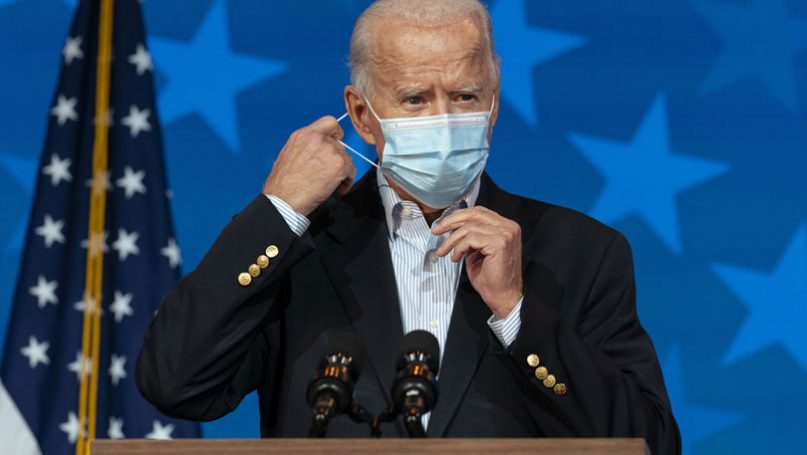

Since 2020, multilateralism was under stress, but the new coronavirus was no gamechanger. COVID-19 deepened the long-term decline of international institutions that marked the 21st century. All this considered, signs of hope for future international cooperation were widely displayed across media, governments and academia. Firsty, by Christmas 2020 the EU and the United Kingdom duly reached a trade deal that (at least for a while) put to rest Brexit anxieties. Then, the outcome of US presidential election saw a victorious Joe Biden portrayed as a key element for reassessing American commitment to Multilateralism, the rule of law – maybe even some kind of international leadership. Both EU and Biden administration committed to providing multi-billion packages of economic aid.

COVID-19 did not hamper international cooperation or domestic change on tracks. This should be cause for celebration. However – that is our argument here – those developments bring not only good news for a specific brand of international cooperation, Multilateralism. On the contrary, the aggregate brings additional warning signs to an already weakened and challenged multilateral architecture. The same events that mobilized hearts and minds for a promising future reaffirm long-term detrimental trends.

In this article, we explore a number of developments that enhanced Multilateralism’s fall. Economic aid packages provided by national governments and communitarian institutions in order to preserve jobs trigger centrifugal effects, negatively affecting international trade and cooperation. Rising indebtedness adds more doubts. Those features limit the impacts of Biden leadership – apart from a long-term declining US status vis-à-vis emerging economies and other competitors. Additionally, the vaccine rush that marked 2021 was undertaken with little to no coordination and lack of rules.

Afterwards, we highlight latent opportunities for multilateral cooperation in the pandemic context, through which Multilateralism can be effectively mobilized in the short run, preserving its future viability in a (still hypothetic) post-COVID world. Combined, such opportunities can weld together broken threads of multilateral framework.

- A shift in US foreign policy, replacing Trump’s autarchic impulses with a cautious approach. Early initiatives in Biden’s foreign policy may reposition the US – a contested superpower, hardly hit by pandemic, struggling to match the pace of emerging powers – as a “unifier” facilitating convergence through multilateral arrangements, rather than a hegemon.

- Then, we approach the current multilateral agenda looking for new articulations between states, societies and institutions. After worldwide efforts for vaccine production in record time (a major achievement), 2021 was marked by public-private partnerships for providing vaccines in proper time to vulnerable populations according to equity rules. Spearheaded by EU and coordinated by WHO, COVAX Facility is an early sign of Multilateralism to come.

- Finally, we explore how unintended consequences of economic recovery packages adopted in the pandemic context may benefit multilateral initiatives in the longer run. Such packages proposed by both EU and US could partially restore global economic exchange and benefit (albeit indirectly) other polities and multilateral arrangements, in the context of lengthier transitions to a “greener economy” (an approach pioneered by China).

Rise and Fall: The United States in a “New World Order”

The fall of the Berlin Wall symbolized a structural transformation in international relations. A skewed order – one whose maintenance arguably would demand a more sophisticated kind of leadership (Gaddis 1986, p. 108) – replaced the relatively simpler bipolar structure of the Cold War.

In early 1991, United States President George Bush announced a “new world order” in the wake of the Second Gulf War, as the leader of a victorious coalition sanctioned by the United Nations. According to Bush senior, after Cold War, international intercourse would follow the rule of law in order to promote international solidarity, funneled through multilateral channels. This depiction of international order, by then, mirrored the image a confident, victorious superpower.

30 years after, the United States Congress was invaded by an angry mob, inspired by President Donald Trump’s reluctance to concede defeat to former Vice President Joe Biden. This deadly assault took place amidst the coronavirus epidemic, which claimed more than half a million American lives.

This overlapping of unprecedented events shocked audiences at home and abroad, providing further evidence of a democratic fallout on a global scale. It also brought to surface the precarious international stance of the US, the country with most COVID-19 cases (more than 32 million). Fuelled by polarization within parties (which prevented a Legislative response to Executive excesses), the Trump administration proved unable to provide a role model for Western democracies, significant institutional investments or sustained leadership at the world stage.

The contrast between 1991 and 2021 provides the background for President Biden’s announcement that “America’s back”. In the meantime, which America?

At the end of Cold War, the US’ economy represented 29% of the world’s GDP[1]. 12 years after, Osama Bin Laden sent videos from his cave hiding in Afghanistan celebrating the twin pronged demise of globalized capitalism – the World Trade Center. By then, US’ GDP neared 1/3 of the global aggregate[2], after a decade of economic growth,. However, since the 2008 global crisis triggered by American real estate collapse, US represented less than 1/4 of the world’s GDP[3] and did not rank among the fastest-growing developed economies. Similar figures appear in patterns of global trade and investment. At the inception of World Trade Organization, Bill Clinton presided over 13% of the world’s exports and 15% of imports[4]. Now, with WTO embroiled in nationalistic warfare ushered in by Trump and straightjacketed since Barack Obama’s administration, figures fell to 10% and 13%[5]. The US provided roughly 1/4 of the world’s FDI by the century’s turn. Now it provides less than 1/5[6].

The Biden administration has a long, hard road ahead looking for a level playing field with China, India, Japan, the EU and emerging economies. Such a recovery could benefit from taking a multilateral route, in a swingback from recurrent sprees of isolationism.

Resort to isolationism has been a recurring feature of US foreign policy, entangled with self-sufficient exceptionalism, nativism, economic protectionism and unwillingness to engage in strategic commitments beyond America (Kupchan, 2020). Between George W. Bush and Trump, Cold War’s major victor reduced the breadth of its foreign intercourse (Knudsen, 2019). Looking unfavorably for domestic competitiveness vis-à-vis rising competitors abroad, succeeding administrations invested in multiple dimensions of autarchy, epitomized by Trump’s “America First” inauguration speech. Instead of reliance on a collective security system (the UN in 1991), across the 21st century US administrations resorted to coalitions of the willing for interventions in Middle East – sometimes shunning deliberations by the UN body (as in Iraq, 2003). Such interventions eventually amounted to little more than a costly distraction from great power competition. Abandonment of multilateral institutions (UNESCO, WHO) were abundant. Even multilateral institutions constructed with explicit American support (WTO, succeeding GATT) were eventually undermined (its Appellation Body) by administrations as distinct as those lead by Barack Obama and Donald Trump. US allies were often pervaded by a sense that a reluctant superpower was turning backs on the world. There was enough cause for concern that multilateral institutions would accordingly decline.

A challenged superpower can hardly afford isolationism. The costs of raising walls against competitors (not enemies) reverts into a less predictable environment, opens windows of opportunism as well as revisionism. The sheet balance of the pursuit of autarchy in an interdependent world is frustrating. Impromptu, piecemeal responses to global challenges proved disastrous across 2020. After a pandemic year with international leadership in short supply, stakes are high for a revamped US role.

If Biden were to invest in a pragmatic rules-based international order, that alone would not suffice to foster lingering stability. Nevertheless, a different kind of leadership could still make a difference.

A Changing of the Guard, a Changing of Leadership

Leadership – the capacity to break through bargaining deadlocks, by either solving or circumventing them (Young, 1991) – provides key contributions to determining collective outcomes. At the light of a shifting world order, contrasting features of leadership make a difference for a multilateral system.

Structural leadership mobilizes systemic asymmetries in favor of a dominant player. Through “arm-twisting”, incentives & coalition building, it converts dominance into a decisive bargain act. Such techniques were actively employed by the Trump administration. For instance, “arm-twisting” in trade policies eventually convinced North American partners to shed NAFTA for a trimmed-down arrangement. Arguably, coalition building proved pivotal for a successful attempt to render Israel recognized by a growing number of Middle Eastern states through the Abraham Accords.

In multilateral terms, nevertheless, those courses of action proved highly detrimental. Punishing bilateral trade policies were pursued at WTO expenses, triggering protectionism in a global scale. Leaving the Paris Agreement, blaming WHO at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic wreaked havoc in key problems of collective action. With the benefit of hindsight, Trump claims to leadership were dramatically limited by his administration’s autarchic impulses. In the nuclear field, simultaneously engaging North Korea and antagonizing Iran left allies baffled. Outcomes were hardly favorable, to either the non-proliferation regime or US’ aspirations. It is uncertain if the aggregate of those activities made America “first” or “great again”.

In contrast, entrepreneur leadership employs insight and creativity in order to identify and bring to light potential joint gains. A large number of actors locked in collective action hazards overlapping with high probability of a bargainer’s surplus favors this kind of leadership, associated with the provision of private or public goods. It helps to be backed by an atmosphere of urgency or crisis – both contingencies at Biden’s disposal.

The first 100 days of the new administration displayed a relentless resolve to revert Trump policies related to multilateral institutions: re-entering the Paris Agreement, re-engaging WHO plus a rapprochement with China in fighting climate change. Reverting a long-standing multilateral retreat, however, requires encompassing strategies for tackling global asymmetries at relative lower costs –reshaping multilateral spaces, in order to accommodate international circumstances.

The costs of maintaining international order and the likelihood that such an order stands still have been prominent features of debates on US foreign policy since the end of Cold War. With limited resources at his disposal amidst international turbulence, Biden’s revaluation of Multilateralism is not surprising. As a relatively inexpensive and durable organizational form (Martin 1991, p.785), Multilateralism remains compelling from the perspective of a far-sighted powerful agent. However, taking the multilateral route also entails displaying ample willingness for burden sharing, more than just providing “a multiplicity of options in an uncoordinated fashion” (Young 1991, 297).

Early displays of newfound disposition for international coordination were shown during April 2021. As a warm-up to the COP-26 conference in Glasgow, Biden invited 40 heads of state for a virtual summit in Earth Day 2021. This minilateral forum represented a stark contrast to Trump’s abrasive isolation. Attempting to deal with differences in ways compatible with institutional commitments, Biden brought to table even polarizing figures (such as populist Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro). Demonstrating that everyone is welcome during agenda-setting is a key move for improving norm-oriented behavior. If no one is forgotten during lawmaking, no one can claim to be above the law. Additionally, Biden built upon flexible commitments of the Paris Agreement by offering additional carbon emission cuts compatible with the pandemic timetable (creating some room for maneuver, welcomed by the current disarray of national public policies, and hinting at eventual convergences).

A diplomatic shift does not employ claims necessarily endowed with universal appeal. Nevertheless, it endorses an open doors attitude towards inclusion and learning. Such proceedings build bridges across social divisions, even though problem-solving remains a more demanding task.

By acting like primus inter pares, Biden adopted a different brand of leadership. By building focal points (a role that demands humility and patience), the US acted as a unifier rather than a hegemon.

From Disarray to Convergence: European Union after COVID-19

Arriving at the tail end of previous cascades of crises in European integration (concerning economy, terrorism and refugees), COVID-19 inflicted additional damage in a dire landscape. Across 2020, European audiences could be excused if they failed to follow the advice of either communitarian or national authorities – in this case, they were not speaking the same language among themselves.

Eventually, the EU reached some commonality in vaccine distribution and economic aid. By December 2020, a 750-billion Euros temporary recovery instrument (NextGenerationEU) was unveiled. Member states reinforced their communitarian commitment and cooperation, balancing internal issues and circumstances under the same footing by adopting a set of underlying principles (noticeably compatible with Multilateralism). Considering that no member state should go on its own, European polities started pooling medical resources, to be shared according to different needs (namely, prioritizing the epicenters). After production shortcomings and delayed implementation, common rules for purchasers (on transparency and equality) were enforced at the community level.

At the same time, the EU pursued a vigorous vaccine diplomacy. Through public-private partnerships the community donated more than 80 million vaccine doses to 42 extra-communitarian states. Reaching out to networks of civil society and subnational entities proved pivotal in circumventing national competition for different vaccine brands. Not to me missed, the EU (through the pharmaceutical facilities of its member states) comprise the largest COVID-19 exporter in the world.

Since late 2020, United Nations’ Secretary General Antonio Guterres provided a steady critique of “vaccine nationalism” on human rights grounds. Calls for turning COVID-19 vaccines global public goods only grew, afterwards. Such normative attempts by the most salient multilateral organization overlapped with European convergence of national policies in early 2021, within the COVAX Facility.

COVAX (COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access) – a joint effort by WHO and the public-private alliance GAVI (Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization) – provided a launching pad for the global governance of pandemic by pooling resources, sharing information, minimizing risk, maximizing procurement and delivery of health services. States can cooperate, in spite of recurrent asymmetries, through this platform: wealthier ones pool resources to buy vaccines for all (including not only middle and low-income states with precarious vaccination coverage, but themselves). A key multilateral dimension comes to the forefront: everybody should be in from the very beginning.

COVAX’s pivotal contribution to global vaccination efforts can be sustained in the future, through multilateral routes. By rendering access to vaccines a human right, rather than an externality treated in ad hoc fashion, global community may be ready to meet other pandemics. Multilateralism can benefit from this recontextualization – and international relations already have relevant precedents.

After surpassing 150 million cases worldwide, the learning curve of the current pandemic already proved immensely costly. One of the lessons learned from the COVID-19 era was that, in a future pandemic context, timely access to vaccines shall be treated as a basic need – to promote equality, as well as to halt efficiently the spread of dangerous and unknown infirmities.

After decades of relentless contestation, growing demands and skirmishes between developing and developed economies, the “basic needs” become a mainstream approach in cooperation for development. In this case, mirroring ODA’s GDP target contributions, a permanent fund for facing pandemics steered by WHO and co-administered by civil society can be established by governments, firms and the Third Sector, sustained by regular donations (following COVAX’s budget). This proposal would arguably come at lower costs than 2020’s pandemic depression.

A New Multilateral Agenda for Pandemic Complexity

The year 2019 ended with Brexit controversies on regional integration, ongoing skirmishes of US-China trade disputes making headlines, under pervasive shadows of climate change. By contrast 2020 ended with global indebtedness highlighting the biggest economic decline since 1929 amidst a pandemic.

The multilateral agenda shifted abruptly, although multilateral institutions kept a low profile. Across this shift, major institutions in different issue areas remained underfunded, intensively contested (or even demoralized), inefficient or considered non-representative enough (Chatham House 2021).

In the absence of overt leadership, little to no coordination of national efforts to curb COVID19 was seen. After a year of lockdowns, 2021 ushered in a vaccine rush, in which more than 1 billion vaccine doses were administered. In spite of this remarkable achievement (different vaccines eagerly produced in record time), there was no overall retreat of the disease, fueled by new coronavirus varieties stemming from different corners of the world. Additionally, several platforms fought for the same constituencies, with seemingly no rules of the road to follow. The emerging issue of “health passports” also raised concerns over the eventual resumption of transcontinental travel.

Through indivisibility & diffuse reciprocity, Multilateralism turns private goods into public goods. A translation of individual interests in terms of shared goals is needed, in order to achieve a convergence in any issue area of international relations (Krasner, 1982). Such features have been lacking during the Trump era and a demoralized WHO could not provide this kind of pull. In spite of inheriting this scenario, Biden may have a different stake in that regard.

This said, it is ironic that, during the year when international trade reached its lowest point in the century and the most salient downfall since the interwar period, both EU and the UK envisioned all efforts to get a trade deal before Brexit (and calendar) elapsed – therefore, avoiding a fallback into WTO regulations. Even in hard times, multilateral routes were prevented, rather than looked for.

Suddenly, complex societies faced a simultaneous supply and demand crisis of unknown magnitude. Global growth disappeared, 85% of assets collapsed in relation to 2019. Confinement prevented the adoption of anti-cyclical measures (government-set fiscal stimulus plus large infrastructure projects), replaced by tax cuts, credit mechanisms, bond emissions and massive cash transfers. In a landscape of lower wages, salaries, demands, investments, international trade and huge budget deficits, the crisis’ spiral culminated with an increase of national responses to little collective action.

A salient feature of this resilient “age of the deal” are economic aid packages installed under COVID-19. They remain pivotal for the foreseeable future. As previously mentioned, in November 2020 the EU superseded disjointed action by unveiling a 750 billion euros economic package. Even before that, polities such as US and Singapore have committed 15% of their GDPs in recovery efforts. This task proved harder for Asian and African countries of lower HDIs and scarcer reserves – implicating a global debt escalation, accompanied by claims that major investors (such as China) offer waive packages – a reprisal of 2008 scenes?

The tunnel vision that presides over aid packages is intrinsically associated with the nation-state as an economic unity. Expectations that such moves eventually induce productivity, employment, competitiveness and prosperity are paved in the short run by protective measures, favorable treatment of local firms, further bureaucratization and centralization, plus skepticism towards “foreigners”. Familiar scenes after crises may induce further tailspins. National problems will likely have long-lasting legacies for institutionalized global cooperation. Symptomatically, in January 2021 Biden announced a 1.9 trillion dollar stimulus plan at the United States accompanied by an executive order restricting government contracts with overseas companies.

So, what can be done to Multilateralism, in order to revert those unfavorable perspectives?

Reshaping Multilateralism with COVID-19 under Way

Another set of policies can engender virtuous synergies, in spite of the devastating effects of the pandemics over developed and developing economies alike. Across 2020, massive indebtedness affected a multitude of polities. G-20 initiative of suspending debt relief payments (October) followed by Zambia’s moratorium (November) highlighted this issue. Debt spirals preclude a quick return to normalcy in terms of successful long-term public investments. Domestic markets will not bounce back easily from dependence on government vouchers. In a global scale, COVID-19 stopped the timid recovery from 2008 on tracks. High debt and fiscal crisis limit states’ horizons of action. Even in the communitarian realm (Eurozone) crisis was met with divergent effects and responses. Moreover, business who benefitted from credit extension will be largely indebted afterwards.

Debt restructuring efforts to avoid a second sovereign debt crisis could contemplate remonetizing the growing debts of worst-affected economies as a systemic task channeled through multilateral institutions. In this case, a convergence of national policies would rely upon a renewed institutional framework. Even though we cannot rely on leadership claims alone for inducing convergence on self-centered national policies, lessons learned since 2008 may render a post-pandemic scenario a swifter landing. One of them consists in accelerating transitions to a “greener” economy.

China took the lead by a series of steps in such direction since 2007, when the notion of “ecological civilization” gained traction under President Hu Jintao (Weng, Dong, Wu, & Quinv, 2015). Such policies were partially responsible for its recovery after 2008 (and 2020 GDP growth, unique among G20 economies). In the Chinese context, greening the economy coalesced after decades of market reforms implemented under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping (Hong 2016) and the learning curve of a rapidly industrializing society that did not experience a similar pace of political liberalization.

The Chinese conception of such a transition involves, firstly, massive government investments in “old” industry and services, backed by prolonged savings. Secondly, the transference of transition costs to subsidiary bodies and firms through technological jumps, reinforcing central management. In a later stage (2010s), President Xi Jinping promoted an ambitious public diplomacy associated with a more sustainable economic model (even though Chinese leaders refrain from using the concept of “green economy”), appealing to international audiences in a vacuum of US leadership.

Nevertheless, some shortcomings remain visible. Greening the economy reinforced the surveillance capacities of the Chinese state, as well as regional disparities. Additionally, Chinese-led initiatives associated with foreign direct investment (the Belt and Road Initiative) are not bound by notions of sustainability – what limits the applicability of this model in multilateral settings.

Some liabilities and limits of a Chinese way can be averted by adopting a multi-stakeholder approach early on, which fosters a cooperative approach to economic transition. That precludes a quick fix to pandemic woes – according to Chatham House, 93 trillion pounds will be required in the course of 15 years to achieve a green economy at the UK. However, it can boost a bolder, broader shadow of the future, compatible with a plurality of circumstances under the sway of multilateral regulations.

Right now, the overall picture is of uncoordinated action, regulated by a loose normativity (the Paris Agreement), allowing for different domestic circumstances. By assessing costs and risks to strike a balance between environment and economy, states attempt to engage social agents in order to keep economy running during crisis. Due to systemic pressures, up to 2019 transitions to a “greener” economy ensued consented competition in a context of limited normativity. However, under the strains of COVID-19 a partial governance scenario is feasible, in which initiative shifts between states and IOs, as well as between subnational agents and firms. Incremental reform at the international stage combined with ambitious re-engineering of development models at home transcends the pursuit of damage reduction through risk management, as well as furthering multilateral ambitions.

Even though still geared towards national variables, economic reform packages by the EU and US can trigger “leakages” to other agents and issue-areas. By merging in complex ways economic impulse and sustainability, such public policies impinge on areas of multiple interdependence, calling other international actions into play. This scenario favors implicates a reframing of national commitments in line with a revamped Paris Agreement (an issue highlighted during Biden’s Earth Day summit and present in COP-26’s agenda). Tensions between national economies and planetary sustenance have already arrived at the multilateral agenda of the present with newfound urgency. In this respect, both attempts at national recovery and rude awakenings to a “greener” economy can eventually benefit the fortunes of Multilateralism – albeit indirectly.

Final Remarks

In this article, we highlighted the prospects for multilateral cooperation in a pandemic context. Even though COVID-19 developments set states and economies further apart, a new push from the Biden administration can provide focal points in a number of issue areas, partially restoring confidence in multilateral endeavors. Centrifugal aid packages can be brought in line by interdependence links, to which growing indebtedness is a major incentive. Building upon recurring lessons, transitions to “greener” economies provide additional leakages between public policies. Finally, rendering access to vaccines a basic need enhances the emerging governance of global health services symbolized by the public-private partnership COVAX Facility.

References

Chatham House (2021). Reflections on building more inclusive global governance: Ten insights into emerging practice. Synthesis Paper, Director’s Office, International Law Programme (April 2021). London: Chatham House.

Gaddis, J. L. (1986). “The Long Peace: Elements of Stability in the Postwar International System”. International Security, Vol. 10, No. 4 (Spring, 1986), pp. 99-142.

Hong, Y. (2016). The China Path to Economic Transition and Development. Singapore: Springer.

Knudsen, E. (2019). “A Century of ‘America First’ – The history of American exceptionalism in transatlantic relations”. Dahrendorf Forum Commentary. Retrieved from: https://www.dahrendorf-forum.eu/publications/a-century-of-america-first/. Access in: January 22 2021.

Krasner, S.D. (1982). “Structural Causes and Regime Consequences: Regimes as Intervening Variables”. International Organization, Vol. 36, No. 2, International Regimes (Spring, 1982), pp. 185-205.

Kupchan, C. (2020). Isolationism: A History of America’s Efforts to Shield Itself From the World. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Martin, L. M. (1992). “Interests, Power, and Multilateralism”. International Organization, Vol. 46, No. 4 (Autumn, 1992), pp. 765-792.

Ruggie, J. G. (1992). “Multilateralism: the anatomy of an institution”. International Organization, Vol. 46, No. 3, pp. 561-598.

Weng, X., Dong, Z., Wu, Q. & Quinv, Y. (2015). “China’s path to a green economy: Decoding China’s green economy concepts and policies”. IIIED Country Report. Retrieved from: http://pubs.iied.org/16582IIED. Access in: April 22 2021.

Young, O. R. (1991). “Political Leadership and Regime Formation: On the Development of Institutions in International Society”. International Organization, Vol. 45, No. 3 (Summer 1991), pp. 281-308.

Notes

[1] World Bank figures

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Multilateralism as Panacea for COVID-19

- Opinion – Can the Coronavirus Crisis Revive Multilateralism?

- Opinion – Coronavirus: A Global Crisis Waiting for a Global Response

- Opinion – Post-COVID-19 Climate Change Politics

- COVID-19’s Reshaping of International Alignments: Insights from Italy

- Covid-19: Learning the Hard Way