Following the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, many museums and heritage sites intensified their concern with diversity and anti-racism. Museums have committed to better value and integrate the perspectives of Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC) and to recurate exhibits to better acknowledge the racist violence of the past. Some applaud these practices, casting them also as integral to the project of decolonizing museums.

However, can museums be decolonized? Like many statues and monuments, they are creations of the colonial era, which may well make this objective unattainable. Yet, some activists claim it is worth pursuing. Others, such as Eve Tuck and K Wayne Yang, object to using the term decolonization with reference to the reform of colonial institutions, and reserve it to designate the repatriation of stolen land and life to indigenous population. These debates have not yet considered the case of war memorials and museums, which we explore here through the case of two memorials to the experiences of Japanese Americans during World War II.

We first consider the Poston Memorial Monument, which is located on the Colorado River Indian Reservation. The Reservation, which stretches along the Colorado River along the border between eastern California and Arizona, was established in 1865 following a negotiation between the Mohaves, who had ancestrally occupied the land, the Chemehuevi, who had moved to the area in the 1800s, and Colonel Charles Poston, the Superintendent of Arizona’s Indian Agency. The gold rush, which brought white settlers to spread from the East towards California, threatened indigenous peoples and ways of life. The settler’s mining ambitions stripped the Mohaves and Chemehuevis of large parts of their land. In the early 1900s, the US government implemented policies designed to erase indigenous culture, such as the forceful displacement of children into boarding schools and the prohibition of traditional ceremonies.

The Colorado River Indian Tribes suffered another dispossession between May 1942 and November 1945 when the government requisitioned the land to incarcerate 17,800 people of Japanese ancestry in camps named after Charles Poston. A few months earlier, US President Franklin Roosevelt had mandated the forced relocation of Japanese Americans into incarceration camps, of which Poston would be the largest. Of the 120,000 Japanese Americans who were forcibly displaced, a third were stationed on Indian Reservations. In addition to Poston, camps were built on Native land at Gila River, Arizona, and Heart Mountain, Wyoming.

After the war, Japanese American activists and camp survivors transformed the former incarceration camps into educational and commemorative spaces. The Poston Memorial Monument was built in 1992, thanks to the collaboration of the Colorado River Indian Tribe (CRIT). The CRIT Council set aside forty acres of reservation land to restore the Poston site and affirm its historical significance. The Council also granted use of one acre of land for a monument, designed to represent a Japanese stone lantern, and kiosk, and currently working on a museum project. The Poston Memorial serves as a symbol for the unity of spirit, collaboration and open conversation between the descendents of Japanese American survivors and Indigenous communities, bonded through their shared experience of confinement and displacement.

The case of the Poston Memorial highlights how the violence of institutionalized racism and settler colonialism intersect. It records how Japanese Americans’ designation as ‘enemy aliens’ led to their incarceration. Individuals of German and Italian descent did not suffer the same fate, evidencing this policy as founded on racialization. Such racialization, as Tuck and Yang note, is a tool deployed by colonial elites to establish control over the territory it has settled and secure the settler elite’s own growth.

However, racialized groups experience the violence of internal colonialism in different ways and to varying degrees. After World War II ended, the Japanese American incarcerees were released and left the camp. In contrast, many indigenous people of the Colorado River Indian Tribe stayed on the reservation. For them, leaving would mean losing their home and community support due to the continual erasure of their cultural heritage outside of the reservation.

These differences complicate solidarity amongst minoritized groups against settler colonialism. It’s uncomfortable to admit, but both white and non-white settlers directly and indirectly benefit from the erasure and assimilation of Indigenous peoples, by occupying stolen Indigenous land and living off forcibly taken resources like water and minerals. There is a risk for Japanese Americans of using the incarceration experience to deny or deflect their own complicity in settler colonialism. Japanese Americans and other non-white settler communities therefore have a shared responsibility to reflect on their implication in colonial processes.

The Poston Memorial Monument should help us see the difference between diversity/inclusion and decolonization at sites of memory. The Japanese American community curated the preserved camps and the memorial in conversation with Native American communities. Non-white perspectives were therefore central to the site’s curation. However, decolonization is more than the representation of BIPOC in curatorial teams and the valorization of their perspectives. Following Tuck and Yang’s more demanding definition, decolonization should produce material changes for indigenous people, such as the repatriation of stolen land and resources.

Can museums and memorials enable such material changes? They may not immediately contribute to material redistribution. However, by educating about past and continuing violence, they can invite visitors to see the decolonization of land and resources as a possible and desirable outcome. Like other sites of memory, The Poston Memorial promotes decolonial thinking by acknowledging indigenous sovereignty, and humanizing native communities by telling their stories. Museums and memorials may also normalize the repatriation of stolen land and artefacts when they agree to restore them to indigenous communities.

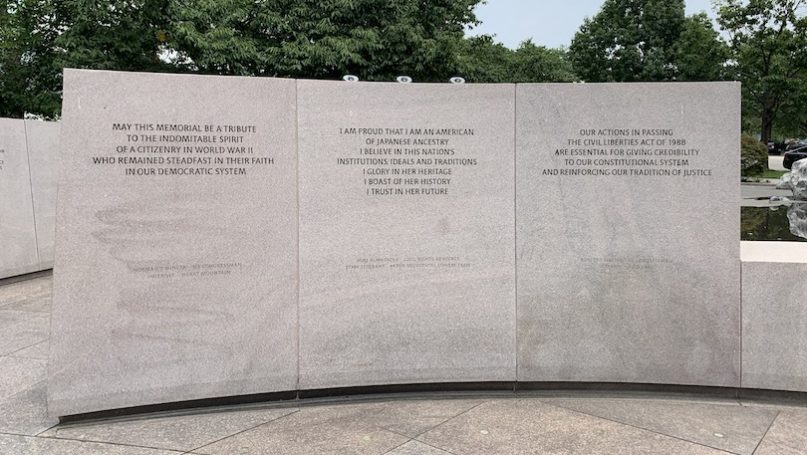

We now turn to a second memorial, the National Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism During World War II in Washington, D.C.. The memorial is located not too far from the US Capitol, a land once populated by the people of Natcotchtank. This memorial pays tribute to Japanese American incarcerees, as well as to Japanese Americans who gave their lives for the US military during World War II. The simple design includes seven quotes engraved in stone walls. The first six quotes are from the Japanese American elected officials Daniel Inouye, Robert Matsui, and Norman Mineta; the US presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry Truman and Ronald Reagan.

The seventh quote is by the wartime Japanese American Citizens League leader Mike Masaoka, and drawn from Masaoka’s controversial Japanese American Creed. The latter promoted an assimilationist strategy during the anti-Japanese hysteria of the 1940s. This strategy included loyalty campaigns promoting the acceptance of the evacuation order as a bid to gain safeguards from the government. Problematically, quoting the Creed in the monument suggests that patriotism is the same as cooperating with the government, including when it enacts racist policies. For similar reasons, many Japanese American camp survivors are opposed to being honored alongside fallen veterans, and question whether the two experiences should be commemorated in the same space.

This discomfort is understandable. By celebrating assimilation and military service as a response to racial injustice, the memorial weaponizes patriotism as a mode of control. Patriotism, in this case, serves to deflect attention away from a settler colonial and racist policy, by celebrating loyalty to a state that operates through colonial modes, rather than question it. This is not to invalidate the choice and valor of Japanese American soldiers whose names are inscribed on the walls of the monument. However, centering their service and emphasizing it as the most valued response to displacement, dispossession and incarcerable is questionable. It distracts from the injustice perpetrated against Japanese Americans and indigenous communities, and from efforts to challenge this injustice.

We conclude with thoughts on the intersection of feminist and decolonial thinking. All quotes engraved on the walls of the DC monument are of men. In contrast, Japanese American women’s voices are silenced. This situation is not unique to the DC memorial. Missing from most public narratives of the internment of Japanese Americans are stories of violence against women. Women ‘experienced incarceration not just as a violation of their civil rights but of their physical safety and bodily autonomy, their freedom of movement constricted not just by barbed wire and high desert but by the constant threat of sexual violence.’ The cramped conditions in incarceration camps created an environment favourable to abuse, and sexual assault is rumoured to have taken place at Poston. Women were harassed, followed, and threatened when moving through public spaces like the latrines and the showers. Many incidents went unreported due to the little trust Japanese American women had in US authorities as a source of protection.

Even if they integrate decolonial thinking, which the Poston Memorial does, memorials do not present a full picture if they focus on men’s experiences of racism and colonialism. Silencing women’s stories allows non-white men to control the narrative of past injustice and hide the ‘stories that bear witness to the ways victims of institutional harm can become perpetrators of individual violence’. Conversely, memorial designs that silence the experience of women perpetuate ‘the silence and sacrifice demanded of women of color from both within and without their own communities’. As they grapple with the challenges of decolonization, diversity, and inclusion, memorials ought to adopt an intersectional perspective, through which experiences of racism and colonial violence can be recognized as mediated by gender.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- New Book – Decolonizing Politics and Theories from the Abya Yala

- Opinion – Decolonizing Development Will Take More than Moral Imperative

- Decolonizing South-South Cooperation: An Analytical Framework

- Decolonising the IR Curriculum: Reflections from a Classroom

- Opinion – Decolonization Is Decisive in the Confrontation with Russia

- Unthinkable and Invisible International Relations