The Soviet propaganda machine created heroes and monsters via exaggerations and, often, lies. Books like The Soviet Propaganda Machine and The Birth of the Propaganda State have researched this topic. However – with notable exceptions – not much has been written in English about the inhabitants of Central Asia who became victims of the propaganda machine. The Kazakhstani scholar and activist Mustafa Shokay (also spelled Çokay or Chokay) is a prime example of the machine at work. His name and legacy have only now begun to be revisited as Kazakhstan has been an independent nation for three decades and a new generation of Central Asian scholars are able to carry out their own historical research.

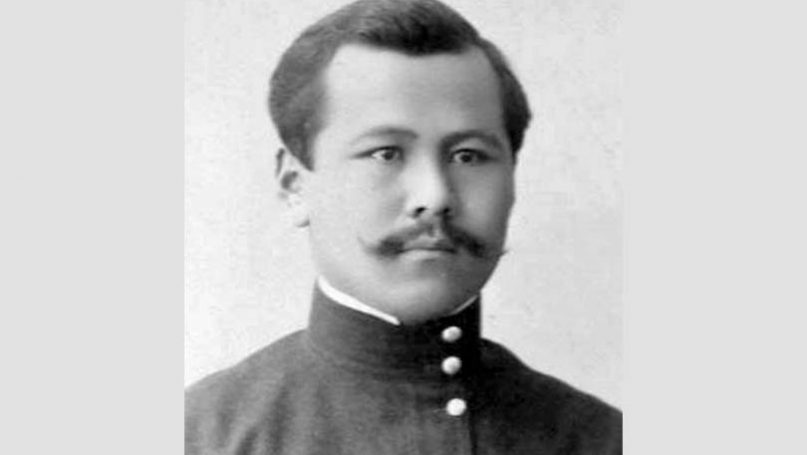

Shokay was born in present-day Kazakhstan in 1890. He studied in Saint Petersburg and eventually became “a secretary of the Muslim faction of the State Duma of Russia on the recommendation of [Alikhan] Bokeikhanov in 1916,” according to the Alash Orda Project. Shokay also reportedly worked in the Committee of the State Duma where he “investigated the causes of the national liberation uprising in Turkestan [and] engaged in the return of the Kazakhs mobilized to the front.” As the Tsarist regime fell and the civil war gained expanded, his goal was for his fellow Turkic people to establish an independent nation, Turkestan, free from Moscow’s control.

To achieve this objective, Shokay became a publicist and editor for Turkic-language magazines and newspapers. According to Zholmakhanova’s co-authored essay, Shokay’s most valuable legacy comes from his writings called 1917 Жыл Туралы Естеліктерден Узінділер, or Excerpts from The Memoirs of 1917. Upon returning to Central Asia in 1917, Shokay “took an active part in Shura-Islami [the Islamic Council], because this organization supported the policy of the provisional government on the development of Turkestan by democratic means; it also fought for the rights of the local population,” Zholmakhanova explains. It makes sense that Soviet authorities took a dislike to Shokay, not only was he advocated the independence of Turkic people, but he also openly insulted Soviet leaders. “Stalin, [is] a vengeful, insidious man, suffering from megalomania,” he reportedly wrote, according to Zholmakhanova.

Eventually, Shokay migrated to Western Europe, settling in Paris. He was reportedly arrested along with other migrants in June 1941, and then imprisoned in Château de Compiègne. He contracted Typhus and was transferred to a hospital in Berlin, where he died on 27 December 1941. Shokay’s death is a matter of controversy, and it is directly related to his time as a Nazi prisoner. He may have died due to Typhus, but it is also believed that he was poisoned. The key issue is the Turkestan Legion, military units composed by Turkic individuals that fought alongside the Wehrmacht. The Legion was mobilized by 1942 and reportedly fought in Western Europe and Yugoslavia.

This is where Shokay comes in. As a prominent activist and scholar who wanted Central Asia to be free of Bolshevik control, it is logical that the Nazis would want him to help establish the Legion by convincing prisoners to join the cause. To what extent he was a willing to cooperate with the Nazis because he shared their beliefs, or if he did it to simply survive the Nazi death machine, is divisive, and the Soviet propaganda machine went to considerable efforts to discredit him in order to tarnish his ideology, legacy and alienate him from his fellow Central Asians.

As a case in point, The Fall of Great Turkestan by Serik Shakibaev (published in Russian in 1972) labels Shokay as a traitor and a willing Nazi accomplice. Other researchers mention Soviet terms that described him as “enemy of the people,” “Kazakh [Andrey] Vlasov,” and “henchman of the fascists.” Abduvahap Kara a doctor of Historical Sciences and professor at Mimar Sinan Güzel Sanatlar University in Istanbul, has written about Shokay and the Soviet-era works on him. For example, in a November review of Shakibaev’s 1972 book, Kara highlights the book’s flaws arguing that it constitutes “a chain of pseudo-events and outright lies” which are “aimed at creating an image of a traitor who tried to subjugate the peoples of Central Asia to the fascists in order to achieve their own goals – to lead Turkestan.”

Kara’s commentary in CentraAsia.org points to nine major flaws, including factual mistakes, in Shakibaev’s book. For example, The Fall of Turkestan claims that Shokai was allegedly involved with British intelligence; however “historical data does not support this thesis. Moreover, it is known that this kind of thesis was usually used by the Soviet government to denigrate the opponents of the Bolshevik movement.” The book also claims that Shokay had the original idea to create the Turkestan Legion, however no evidence exists about this claim (Kara has authored a book on Shokay in Russian).

It is unclear to what extent Shokay believed in Hitler’s ideals and objectives. He would have probably supported any entity that was anti-Soviet and would help Turkic people become independent. On the other hand, it is more likely that while he was imprisoned and meeting with POWs, which meant visiting war prison camps, he realized what the Nazism signified.

Nowadays, there is a statue in his honor in France, a 2008 biographical movie, while conferences and events are organized in Kazakhstan about his legacy. We may never know the cause of Shokay’s death, whether it was a natural illness or if the Nazis decided to get rid of him for not supporting the Legion. However, we know that he was an activist, scholar and editor that was deeply anti-Bolshevik and wanted Central Asia to become free from Moscow’s rule. The Soviet Union’s propaganda machine discredited him; however, an independent Kazakhstan has allowed a new wave of historical research. The restoration of Mustafa Shokay’s name and legacy via academic publications and commemorations in recent years is a fascinating development that should serve as an encouragement to further research the role of Central Asian individuals during Soviet times and to help separate fact from fiction.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Coming in from the Soviet Cold: Feminist Politics in Kazakhstan

- Opinion – Kazakhstan’s Aspirations for Afghanistan Post-US Withdrawal

- Soviet Foreign Policy in the Early 1980s: A View from Chinese Sovietology

- Western Fact Finders: Entering the Soviet Union

- The Lasting Repercussions of Kazakhstan’s Nuclear Disarmament

- Responses From Central Asian States to the Russian Invasion of Ukraine