This article aims to be an intervention into the recent discussions on the importance anxiety and ontological security in the study of International Relations (IR) (Kinvall and Mitzen, 2020; Hom and Steele, 2020; Rumelili, 2020). The paper poses an alternative critical starting point based on the Marxist concept of alienation. Marx’s work on alienation continued in historical materialist traditions such as in Lukács’ (1971) analysis reification has a lot to offer to the discussions on emotions and anxiety and the development of a politically relevant critical theory of IR. My purpose is to draw attention to the potential of Marxist social theory and particularly the concept of alienation in contributing to the development of an emancipatory critical IR theory. Most of the recent discussions on anxiety remain at an abstract level. The recent existential accounts of anxiety and ontological insecurity have subjectivist and idealist conceptions failing to account for the structures of power and domination in capitalist society. However, Marx’s concept of alienation deals with the consequences of power and domination in a more historically specific way (Sayers 2011, 1) providing the basis for a more meaningful social critique oriented to human emancipation.

In the first section, I focus on Marx’s analysis of alienation and what it implies for the study of IR. The article then engages with the relation between existentialism and Marxism as this is the focus of research on the importance of anxiety in recent IR literature. I compare Marx’s concept of alienation with existentialist focus on anxiety. My argument is that whereas existentialism conceptualizes anxiety as an ontological condition of the world, Marx focuses on the historically objective conditions and relations of capitalism as the primary source of alienation thus providing us a perspective which is historically concrete and politically relevant to the study of IR. I conclude with some general observations on Marxism, alienation, anxiety and change.

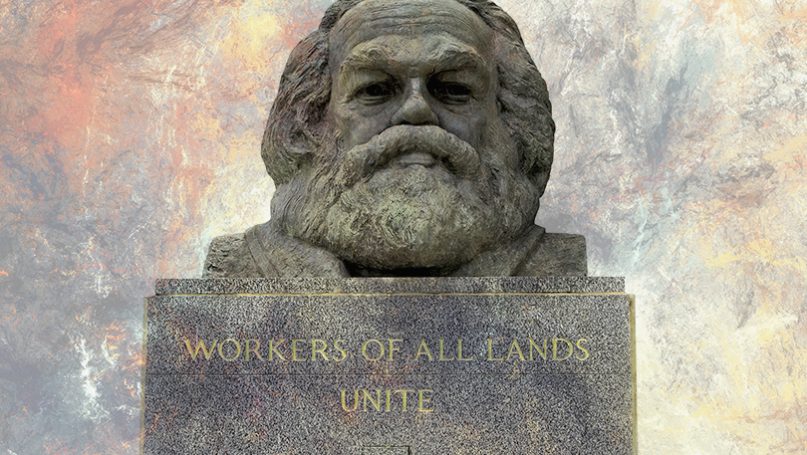

Alienation and Marxism

The concept of alienation is used in diverse ways by different scholars. It is thoroughly a contested concept. In its most general sense, it expresses a pathology of modern life. In the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, David Leopold (2018) defines alienation as ‘a distinct kind of psychological or social ill; namely, one involving a problematic separation between a self and other that properly belong together’. According to Erich Fromm, Marx’s concept of alienation means that ‘man does not experience himself as the acting agent in his grasp of the world, but that the world (nature, others and he himself) remain alien to him’, ‘stand(ing) above and against him as objects, even though they may be objects of his own creation’ (Fromm 1961, 44). In short, the concept involves the separation of the subject from the object in modern society and the object in turn dominating the subject. Alienation is sometimes used to refer to individual psychology (subjective alienation), but more generally used in a more sociological sense to refer to the social relations themselves (objective alienation) (Sayers 2011, 287; Leopold, 2018). When used subjectively referring to individual alienation, it usually denotes a feeling of malaise or meaninglessness in modern society. Concepts of alienation and reification are closely related with each other, but I want to keep them distinct and define alienation in a wider sense than reification and define reification as a radical and specific case of alienation particularly visible in capitalist society.

Rousseau (1712–1778) is credited with the first use of the idea of alienation but it is in the writings of Schiller and Hegel that the concept was fully developed (Kain, 1982). However, Hegel (1770–1831) was the first to give a systematic account of alienation in The Phenomenology of Spirit (Hegel,1977; Dupré, 1972). Hegel used the concepts Entäusserung (self-externalization) and Entfremdung (estrangement) to describe the process whereby the Spirit or what he called the Geist which was at the root of everything differentiated itself or became ‘alien’ in the form of different objects (objectification) in the world. He defined alienation as our failure to realize that our essence lies in the Absolute. One would be free and overcome alienation when reason realized that one’s objectification is part of the Geist or the Spirit.

Marx was influenced by Hegel’s philosophy but for him alienation is not a merely subjective feeling or appearance but an objective social and historical condition (Sayers, 2011, 2021; Evans 2021, 12). However, although freedom always remained at the center of his philosophy (Mészáros,1972), Marx did not have a fixed understanding of alienation and the way he uses the concept changes throughout his works (Kain, 1982). The concept is generally associated with Marx’s early ‘humanist’ works especially as developed in the 1844 Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts (1981). However, humanist and Hegelian themes exist in Marx’s later ‘scientific’ works as well such as the German Ideology (1932) and Grundrisse (1993)(Creaven, 2015; Kain, 1988). As Kain argues (1982: 157) ‘Early and late, the humanization of man is seen as the end of human history, of social interaction and production’.

1844 Manuscripts were published in 1932. For that reason, Marx’s views on alienation as formulated in his early works did not attract enough attention before this date. For instance, The Hungarian Marxist Georg Lukács (1885–1971) used the concept of reification instead of alienation to understand the consequences of capitalist social relations. Lukács (1970) based his arguments on Marx’s analysis of commodity fetishism as analysed in Capital rather than on Marx’s early works. In the chapter on ‘Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat’ of History and Class Consciousness Lukács defines reification (Verdinglichung) as nothing but the fact ‘that a relation between people has taken on the character of a thing’ in modern capitalism (1971, 83). However, the publication of the Manuscripts popularized the concept of alienation. The first generation of the Frankfurt School philosophers further developed Lukács’ ideas on reification. Eric Fromm (1962, 59) extended Lukács’ theory of reification in conjunction with existentialism. In Escape from Freedom (1941), Fromm named the psychology of the period as the ‘marketing orientation’ to denote a mode of existence in which people experienced themselves and others as commodities to be marketed. Recent years on the other hand have seen the revival of interest in the concept of reification and alienation as witnessed in the remarkable works of Axel Honneth (2008), Jahel Raeggi (2014) and Anita Chari (2010, 2015).

In the Manuscripts, Marx deals with the problem of alienation in terms of alienated or estranged labor caused by exchange and division of labor. In the early works, unalienated labor is defined as the essence of being and has a transhistorical and universal characteristic. In his later works however labor is treated in its historical specificity in the context of capitalist social relations rather than as a transhistorical feature of human beings (Postone 2003, 4). It is however with the description of alienation in capitalism in Volume one, Chapter one of Capital (1970) that Marx’s analysis is particularly known. Marx argues that what is specific about capitalism is that labor power itself becomes a commodity. This makes commodity the dominant economic as well as the social form of relationship in capitalist society. The commodity form Marx argues ‘is a definite social relation between men, that assumes, in their eyes, the fantastic form of a relation between things’ (1970, 77). In explaining this, he makes a reference to the ‘religious world’ where ‘the productions of the human brain appear as independent beings endowed with life’; ‘so it is in the world of commodities with the products of men’s hands’ (1970, 77).

As the commodity form is the basis of social life in capitalism, alienation is not only about economy, but its consequences pervade all aspects of social relations. The relation of the individual to the state and by analogy to the relations between the states is one key example particularly relevant for IR. In the Marxist sense, the state is a form of alienation whereby man relinquishes his power to rule but who in turn is dominated by the state as an external force.

Mark Rupert’s work (1993) is significant in demonstrating the alienated social relations and the relation between the states. Rupert develops Marx’s ideas on alienation to argue how the relations between states as defined by the neorealist theory ‘presuppose relations of alienation in which “politics” assumes an identity distinct from “economics” and attains its own institutional form of expression’ (Rupert 1993, 67). In the words of Rupert (1993, 67), this makes international relations,

a second order alienation … historically constructed among political communities (states/societies) which are themselves constructed on the basis of relations of alienation (i.e., the corresponding separations of the producer from the means of production, of political from economic relations, etc.).

Therefore, the very experience of such social spheres such as the domestic and the international, state and society or the individual and society as separate fields of human activity is itself a product of modern capitalist conditions and an expression of estrangement.

Alienation and the Existentialist Concept of Anxiety

Drawing on existentialism and particularly on the views of Kierkegaard and Heidegger, it has recently been argued that ‘anxiety needs to be integrated into International Relations (IR) theory as a constitutive condition of the “international”’ (Rumelili 2020, 257). How does Marx’s theory of alienation and the discussion above fair with this recent interest in Kierkegaard and Heidegger’s views on anxiety as the basis of fear and ontological insecurity in international relations? (Rumelili 2020; Kinnvall and Mitzen, 20020; Steele, 2020). My argument is that similar to Marx’s theory of alienation and his criticism of the abstract, transhistorical nature of human essence, the concept of anxiety as it is proposed in the present literature is also devoid of critical content in that it ignores the historical specificity of social relations under capitalism that lead to anxiety. Therefore, the concept of anxiety, I want to argue, is insufficient to provide a politically meaningful critique of international relations unless related to historically specific social relations created by the capitalist mode of production.

During the post-war period, many principles of Marxism were subject to re-examination based on the experience of the existing socialisms as well as the contradictions of advanced industrial society. Many of the existentialist philosophers were concerned with the anxiety created by the culture of modernity, resulting in alienation, dissociation, marginalization. French thinkers who returned to 1844 Manuscripts saw in Marx’s idea of alienation the basis for generating a new humanist Marxism. Many Marxist thinkers themselves resorted to existentialism to remedy the absence of a focus on the human subject in the more ‘scientific’ works of Marx such as the Grundrisse and Capital. Therefore, a rapprochement between Marxism and existentialism started at the end of 1960s.

As Poster mentions, by 1968 Marxism and existentialism were approaching a synthetic ‘existential Marxism’ (Poster 1975, 35). Existentialist philosophers however have given a different interpretation of the pathology of modern society as compared to that of Marx. Marx was concerned with the alienating conditions under capitalism resulting in exploitation and dehumanization of work force. When explaining this, he was referring to a historically specific phenomenon created by capitalism. Existentialist philosophers on the other hand focus on anxiety as a general, transhistorical, ontological feeling of impasse and meaninglessness relating to this world (Sayers 2021).

Expressed in very general terms, according to the existentialist philosophers, the estrangement of the individual is a natural condition of the world and is not something which is particularly historical and specific. Existentialist philosophers such as Kierkegaard (2014), Heidegger (1962) and in a more secular way Jean-Paul Sartre (1966) all argued in different ways that individuals were fearful of their existence and failed to find value in their lives. For instance Kierkegaard describes anxiety/dread/angst as unfocused fear and articulates our complete freedom to choose as in the example of a man looking over the edge of a cliff or tall building deciding whether to jump or not. Kierkegaard called this ‘dizziness of freedom’(2014, 188) by which he meant the feeling of dread when one is faced with the freedom to choose. The implications of Heidegger’s views are similar.

For Heidegger ‘fallenness’ is an ‘ontological’ characteristic of ‘Dasein’ (Heidegger 1962, 220) Alienation for Heidegger focuses on the inauthenticity of our interactions leading to the ‘rule of the they’ where ‘everyone is the other, and no one is himself’ (Heidegger 1962, 162; Evans 2021, 4). Likewise for Sartre, anxiety was a fixed feature of human freedom and it was impossible to distinguish it from the being of ‘human reality’ (Sartre 1966, 30). As he argued ‘man did not exist first in order to be free subsequently; there is no difference between the being of man and his being-free’ (Sartre 1966, 30). Thus, while Marx focused on the social aspects of alienation, philosophers such as Heidegger and Kiergaard focused on its ‘spiritual’ (Jaeggi 2014, 9; Sayer 2011, 4) or its ‘mental dimension’ (Kavoulakos 2019, 54–55).

Referring to Heidegger, Mészáros argues that, in existentialist accounts ‘socio-historical characteristics of capitalist alienation’ are mystified by taking the ‘unconscious condition of mankind as the ontologico-existential structure of Dasein itself’ (Mészáros 2011, 283). Therefore, as anxiety is defined as a transhistorical and an ontological problem, it is fair to say that these explanations cannot tell us why anxiety is specifically a ‘modern’ phenomenon (Evans 2012, 12). The same criticisms I think also broadly apply to the very valuable recent theoretical advances made in the theory of alienation and reification by Axel Honneth (2008) and Rahel Jaeggi (2014). For instance, following a similar line of interpretation, Kavoulakos, (2019, 54-55) argues that Honneth reduces the social and material dimensions of reification to ‘its mental dimension’, and therefore cannot offer ‘a social explanation of reification’. Likewise, Evans (2021) shows that Jaeggi’s theory of reification cannot demonstrate the historical specificity of alienation and the form it takes under capitalism.

These explanations of alienation / reification and anxiety distinguish the work of these scholars from the work of Marx who sees alienation as specific to capitalist relations of production thus making it difficult to use these conceptualisations as the basis for ‘social critique’ (Haverkamp 2016, 66). As Sayers argues, the philosophies of existentialist philosophers such as Kierkegaard and Heidegger do not adequately take into account of the social barriers for the realization of freedom (Sayers 2021, 9) which make an unalienated or ‘dereified’ social life difficult to achieve. However, as Sayer notes, ‘the very existence of a self which can experience alienation and inauthenticity and seek to overcome them is a social and historical creation’ (Sayers 2021, 9). Therefore, any explanation that fails to take into account the historical nature of alienation, reification and anxiety is bound to have limited value in terms of social change and emancipatory critical theory.

We can develop this criticism further to take into account of the alienated relations between the states as discussed above with reference to Rupert’s interpretation of the relation between states as a ‘second-order alienation’. This implies that the existential situation of human beings (and of states) in modern capitalist (international) society should not be confused with the position of human beings (states) in general. This was indeed the basis of Rousseau’s critique of Hobbes around which the recent analysis of anxiety is built (Rousseau 2003, Book 1, Section 2; Rumelili 2020). In criticizing Hobbes’s conception of the state of nature, Rousseau argued that Hobbes was confusing the social qualities which men assumed in modern society such as greed and selfishness with men’s eternal qualities which existed in the state of nature. This is similar in its implications to the differentiation between historical and transhistorical analyses of alienation and reification. Indeed, one of the contributions of Marx was to extend Rousseau’s critique to demonstrate that it is not society as such but capitalism which creates these alienating conditions (Coletti 1971).

Consequently, this criticism leads to a conception of international relations substantially different from the focus on fear created in the state of nature envisaged by Hobbes and can equally be extended to existential philosophers’ conception of the human condition who assume that anxiety is a general feature of the human condition as opposed to having been created by the exploitative conditions under capitalism (Yalvaç 2007).

Conclusion

In this article, I have discussed the concept of alienation in the context of the recent application of the concept of anxiety as a constituting moment in international relations. My main argument is that when discussing anxiety as the constitutive feature of international society, we should be talking about something social and historical rather than transhistorical and ontological for a critical and politically relevant approach to international relations. I believe that Marx’s concept of alienation provides such a historical and politically relevant conception of IR. Unlike the concept of alienation used in Marxist theory as a historically specific aspect of social relations in capitalism, a transhistorical concept of anxiety makes it impossible to link it with a socially meaningful emancipatory practice and change.

Given the importance of radical change in Marxist theory, it is obvious that Marxist theory should also do more work on the ‘first image’ or on the personal domain and extend its reach beyond the current interest in historical sociological analysis of IR (see Weyher 2012) for a more encompassing critical theory of IR. The personal domain is indeed part of the dialectically interrelated spheres of society, state and international relations. However, this dialectical inter-relation should not be thought of in terms of the false different levels of analysis problem but in terms of a unity of analysis conceptualization as these different spheres of social life are parts of the same totality despite their alienated forms of appearance under capitalism.

References

Chari, Anita. 2010. “Toward a political critique of reification: Lukács, Honneth and the aims of critical theory.” Philosophy and Social Criticism 36, no.5: 587–606.

Chari, Anita. 2015. A Political Economy of the Senses: Neoliberalism, Reification, Critique. Columbia University Press: Columbia.

Colletti, Lucio. 1973. Marxism and Hegel. Verso: London.

Creaven, Sean. 2015. “The ‘Two Marxisms’ Revisited: Humanism, Structuralism and Realism in Marxist Social Theory.” Journal of Critical Realism, 14. no.1: 7-53.

Dupré, Louis. 1972. “Hegel’s Concept of Alienation and Marx’s Reinterpretation of it.” Hegel Studien, 7: 217-236.

Evans, Justin. 2021. “Rahel Jaeggi’s theory of alienation.” History of the Human Sciences, 23, no. 4, 1-18. DOI: 10.1177/09526951211015875.

Fromm, Eric. 1941. Escape from Freedom, New York: Rinehart & Co. 1941.

Fromm, Eric. 1961. Marx’s Concept of Man. New York: Frederick Ungar.

Haverkamp, B. 2016. “Reconstructing Alienation: A Challenge to Social Critique?”. Krisis 1: 66–71.

Hegel, G.W.F. 1977. Phenomenology of Spirit. Translated by A. V. Miller. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heidegger, Martin. 1962. Being and Time. Translated by J. Macquarrie and E. Robinson. Oxford, Blackwell.

Hom, A. and B. Steele. 2020. “Anxiety, time and ontological security’s third-image potential.” International Theory, 12, no.2: 322-336.

Honneth, A. 2008. Reification: A New Look at an Old Idea. Edited by M. Jay. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kain, Philip. 1982. Schiller, Hegel, and Marx : State, Society, and the Aesthetic Ideal of Ancient Greece. Toronto: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Kain, Philip J. 1988. Marx and Ethics. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Kavoulakos, K. 2019. “Reifying Reification”. In Axel Honneth and the Critical Theory of Recognition edited by V. Schmitz, 41-68. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kierkegaard, S. 2014. The Concept of Anxiety. New York: Liverlight.

Kinnvall, C. and J. Mitzen. 2020. “Anxiety, fear, and ontological security in world politics.” International Theory, 12, no.2: 240-256.

Leopold, David. 2018. “Alienation.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy edited by Edward N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/alienation (Accessed 14 November, 2021).

Lukács, Georg. 1971. History and Class Consciousness. Translated by Rodney Livingstone. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Marx, Karl. 1970. Capital: Vol 1. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Marx, Karl. 1981. The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Marx, Karl. 1993. Grundrisse: Foundation of the Critique of PoliticaL Economy. London: Penguin Books.

Marx, Karl and F. Engels.1932. The German Ideology. https://www.marxists.org/archive/ marx/ works/1845/german-ideology/ch01a.htm (Accessed 29 March 2021).

Mészáros, István. 1972. Marx’s Theory of Alienation. London: Merlin Press.

Poster, Mark. 1975. Existential Marxism in Postwar France: From Sartre to Althusser. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Postone, M. 2003. Time, Labor and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx’s Critical Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jaeggi, Rachel. 2014. Alienation. Edited by F. Neuhouser. Translated by F. Neuhouser and A. E. Smith. New York, NY: Columbia University Press

Rousseau, Jean Jacques. 2003. On the Social Contract. New York: Dover Publications.

Rumelili, Bahar. 2020. “Integrating anxiety into international relations theory: Hobbes, existentialism, and ontological security.” International Theory, 12, no.2: 257-272.

Rupert, Mark. 1993. “Alienation, capitalism and the inter-state system: Towards a Marxian/Gramscian critique.” In Gramsci, Historical Materialism and International Relations edited by Stephen Gill. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sartre, Jean Paul. 1966. Being and Nothingness. Translated by H. Barnes. New York: Philosophical Library.

Sayers, Sean. 2011. “Alienation as a critical concept.” International Critical Thought, 1, no.3: 287-304.

Seyers, Sean. “The Concept of Alienation in Existentialism and Marxism: Hegelian Themes in Modern Social Thought”. https://www.academia.edu/3035430/The_Concept_of_Alienation_in_Existentialism_and_Marxism_Hegelian_Themes_in_Modern_Social_Thought

Thompson, Michael J. 2019. “The Failure of the Recognition Paradigm in Critical Theory”, 243-272. In Axel Honneth and the Critical Theory of Recognition, Political Philosophy and Public Purpose. Springler International Publishing. E book. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91980-5_10

Weyher, L. Frank. 2021.” Re-reading Sociology via the Emotions: Karl Marx’s Theory of Human Nature and Estrangement.” Sociological Perspectives, 55, no. 2: 341-36.

Yalvaç, Faruk. 2007. “Rousseau ‟nun Savaş ve Barış Kuramı: Adalet Olarak Barış” (Rousseau‟s Theory of War and Peace: Peace as Justice). Uluslararası İlişkiler, 4, no. 14: 121-160.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The ‘Failure of Critical Theory’ as an Ideological Discourse

- Against Mystification, or What Went Wrong with Critical IR

- Rethinking Critical IR: Towards a Plurilogue of Cosmologies

- Reflections on Critical Theory and Process Sociology

- Rethinking World Systems Theory and Hegemony: Towards a Marxist-Realist Synthesis

- Why Is There No Minor International Theory?