Whether in geo-politics or geo-economics the idiom, “he who pays the piper calls the tune” is almost as old as humanity, and the idiom “who pays for the UN” is certainly as old as the UN How we pay for the UN. is a formula which dates to the end of WW2 and to the power-structures which prevailed at the time of the UN’s gestation, the creation of the Bretton Woods institutions, and of course post-war geo-politics and geo-economics. Delicately, it was a formula which considered the mess left by global war and the power structures of a new world order, who would have to shoulder geo-political and geo-economic responsibilities for the post-war recovery. So much has happened in world politics and economics since that of course the reader is entitled to consider why these formulas have not also fundamentally changed?

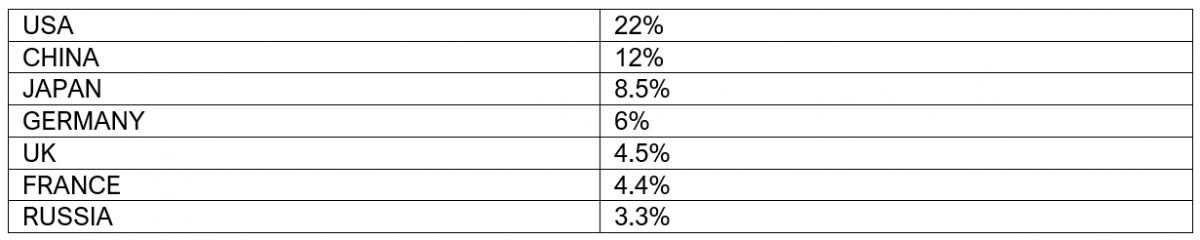

In 2021 funding to the UN Budget provided by the following countries is cited (below) in percentages:

Normally in life we would expect the biggest treasurer to have the most influence but in the UN system the most powerful remain the permanent five members, their powers solidified on the cold cement holding up the first UN flagpole erected in 1947. Veto power in the Security Council lies firmly with those permanent five so the UN is not an organization recognizing the principle “pay to play.” How about the UN charter, founded on Sovereign Equality and Big Power Politics? should tiny Tonga with a mere 100 000 inhabitants continue to have the same voting power as USA or China? Now voting power in the UN system means many different things so we should not get carried away on a pipe dream of sovereign equality. It is more realistic to regard the UN as a global entity frozen in geo-political time and hamstrung by the delicate mechanisms of a 1945 clock which threatens at any time to send the whole planet back into upheaval. It is a bit like the plumber and the old plumbing. Tinker with the UN’s governance at your peril.

The United States and UN Funding

Under President Trump so much fuss surfaced that one might have concluded that the USA was the sole, not just the biggest, paymaster to the UN. The USA does remain by far the single largest financial contributor to the UN system, even after Trump has gone, and is likely to steer a more generous path under Joe Biden. The Council on Foreign Relations proceedings are revealing about American attitudes to the vexed subject of UN power, and whether it is cash worth paying. US Congress has long debated if American contributions are value for money. The Trump Administration consistently proposed significant decreases in UN funding and withheld funding to several UN bodies. At the same time, as is its way, Congress went ahead anyhow and funded most UN entities at higher levels than the Administration requested. The Biden administration supports re-engaging with the UN; the President’s FY2022 budget request proposed fully funding UN entities and paying selected U.S. arrears.

UN System Funding and whether it equates to anything like geo-political power is a different matter altogether. The UN system comprises interconnected entities including specialized agencies, funds and programs, peacekeeping operations, and the Secretariat itself. The UN Charter, ratified by the United States in 1945, requires each member state to contribute to the running expenses of the organization. The system is financed by assessed and voluntary contributions from UN members. Assessed contributions are required dues, the payment of which is a legal obligation formally accepted by a country when it becomes a member. Such funding provides UN entities with a regular source of income to pay for staff and implement core programs. For example, the UN regular budget, specialized agencies, and peacekeeping operations are all financed by assessed contributions. Voluntary contributions primarily finance elective projects, UN funds and programs. The final budgets for these entities may fluctuate annually depending on donor contribution levels.

The UN regular budget supports the core administrative costs of the organization, including the UN General Assembly, Security Council, Secretariat, International Court of Justice, special political missions, and human rights entities. The regular budget is adopted by the Assembly and used to honor a two-year period; however, in 2017 the Assembly voted to change the budget cycle to a one-year cycle beginning in 2020. Most Assembly decisions related to the budget are adopted by consensus. When budget votes occur (which is rare) decisions are made by two-thirds of the majority of members present and voting, with each country having a single vote. The approved regular budget for 2022 is $3.12 billion (constituting about $10 per person in the USA). The General Assembly determines a scale of assessments for the regular budget every three years based on a country’s capacity to pay.

Most recently, the Assembly adopted assessment rates for the 2022-2024 period in December 2021. The U.S. assessment is currently 22%, the highest of any UN member, followed by China (15.25%) and Japan (8.03%). What do Japan, or Germany for that matter get for their cash? Well, I suppose that is the very conundrum before us – power is different from money in the UN language, and money while equating to power, does not undue the complex power formulae conceived at the birth of the UN. For a start, cash is inevitably reflected in the levels of representation of each country in the organization and so (to some extent) influencing the contours of the UN By sponsoring bespoke positions or contributing generously to the Junior Professional Officer’s programme, member states can marginally increase their staffing presence at the UN This should not influence UN policy, but there are no members who do not want their state better represented in the UN system.

The UN Specialized Agencies

Now how does that leave the heavy lifers, the UN Specialized Agencies, who do most of the UN’s operational work? The short answer is often hard up for cash. The 15 UN specialized agencies, which include the World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and World Bank Group (WB), among others, have autonomous executive, legislative, and budgetary powers. Some agencies follow the scale of assessment for the UN regular budget, while others have bespoke formulas to determine assessments. Often, they must shake a tin box and campaign, especially in times of severe crisis. And when is a UN agency not in severe crisis? “Life at the UN” is surely the very definition of crisis? Operationally virtually all UN specialized agencies struggle from budget point to point, occasionally facing guillotine periods, when official spending is severely curtailed.

UN Peacekeeping Missions

The we have UN peacekeeping funding. There are currently over a dozen UN peacekeeping missions worldwide with over 80,000 military, police, and civilian personnel. UN Security Council resolutions establishing new operations specify how each mission will be paid. In most cases, the Council authorizes the General Assembly to create a kitty for each operation funded by assessed contributions; recently, the General Assembly temporarily allowed peacekeeping funding to be pooled for increased financial flexibility due to concerns about budget shortfalls. The approved budget for the 2021-2022 peacekeeping fiscal year is $6.37 billion (the equivalent of about $20 per person in the US). No, the UN does not take the money off homeless Americans, but you get the idea, some American must pay that overall share if the biggest contributor’s bar bill is to be settled!

The peacekeeping scale of assessments is based on modifications of the regular budget, with the five permanent Council members assessed at a higher level. The current U.S. peacekeeping assessment is 26.94%; however, Congress has capped the U.S. contribution at 25%. Other top contributors include China (18.68%) and Japan (8.03%) neither of whom put any sizable forces in genuine harm’s way on peacekeeping- but they do help pay the bills! The reason for the lack of ground forces contributed by these countries (and this also applies to Germany) is historical.

American Arrears to the UN

Congress has authorized funding to the UN system as part of Foreign Relations Authorization Acts. When authorization bills are not enacted, Congress has waived such requirements and appropriated funds the UN through the Department of State and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) accounts in annual Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriations bills. President Biden’s FY2022 budget request includes the following: $1.66 billion (about $5 per person in the US) for the Contributions to International Organizations (CIO) account, which funds assessed contributions to the UN regular budget, UN specialized agencies, and other international organizations (a $157 million (approximately $0.48 per person in the US) increase over enacted FY2021 funding of $1.51 billion (about $5 per person in the US)). The request fully funds UN bodies and includes $82.4 million to pay U.S. arrears that accumulated due to U.S. withholdings from UN human rights bodies (Including the Human Rights Council) from FY2018 to FY2020. That is the biggest tab well on its way to be settled!

Congress also requests $75 million (about $0.23 per person in the US) to pay one year of assessments to the UN Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and includes waiver language to provide authority to rejoin the organization. UNESCO has been a prickly subject for Americans and under DG Federico Mayor Congress got so minded about apparent UNESCO “political radicalism” that they stopped funding altogether for about a decade. Luckily that did not happen, even under President Trump who was no fan of UNESCO programming. It is hoped that the US Congress would fully fund UN peacekeeping beyond the enacted 25% cap and includes $300 million to begin paying U.S. arrears accumulated since FY2017, a lot of taxpayer dollars! That is still likely!

An additional $580 million (about $2 per person in the US) of American money alone in FY2021 was sent under Sec. 10005 of the American Rescue Plan Act (P.L. 117-2) for the UN Global Humanitarian Response Plan to COVID–19. The United States also provides voluntary contributions to UN entities through other SFOPS accounts. According to USAID, the United States contributed $5.5 billion to UN entities through the global humanitarian accounts in FY2019, including Migration and Refugee Assistance, International Disaster Assistance, Food for Peace, UN High Commissioner for Refugees, World Food Program, among others- more than $775 million.

Then we must consider USA contributions to settling all those old bar bills’ I.e., American’s contribution to its outstanding UN debts. From the time of the Reagan Administration withholdings to UN bodies in the 1980s, US payments tended to be paid in arrears – but nowadays that is less a matter of financial principle (i.e., discreetly putting the squeeze on the UN for payment by results) than about the diverse ways the US treasury and the UN machine work. It usually means that someone in the UN is nervously waiting on American funds.

Over the years, policymakers have expressed concern that current regular budget assessments levels result in the United States providing the bulk of funding while having minimal influence on the budget process. Some have called for increased transparency in the process for determining the scale of assessments. Conversely, others contend that the current assessment level is equivalent to the U.S. share of world gross national income. They argue that it reflects US commitment to the UN, affirms U.S. leadership, leverages funding from other countries, and helps the U.S. achieve its goals in UN fora. The good news is that the US peacekeeping cap is less serious now and even there has been a good start on paying back those cap-arrears. It is, by any standards, a significant part of international spend from the US taxpayer, which is why it is always so controversial in Congress.

The USA as the biggest player has simultaneously deployed both carrot and stick over the years to achieve what Congress regards at varying times as results from the UN Congress has attempted such influence by enacting legislation linking U.S. funding to specific UN reform benchmarks or activities. For example, it has withheld or conditioned funding to UNESCO, the Human Rights Council and UN activities related to the Palestinians. It has also limited U.S. payments to assessed budgets (e.g., the 25% peacekeeping cap). From FY2014 through FY2020, SFOPS bills linked U.S. funding to UN whistleblower protection policies. Some Congresspeople oppose such actions due to concerns that they may interfere with US influence and negatively impact its standing in UN fora. Others maintain that the United States should use its position as the largest financial contributor to push for reform, in some cases, by withholding funding. Like so many things about the UN the result is likely to involve a lot of talk but not much change, and even less “small change” for the American taxpayer, but that is the inevitable destiny of being the biggest moneybags of all the big five.

This naturally leads to the question, after paying all this money, Who Really Runs The World? Some new studies of the UN shed light on that issue, showing that geo-economically powerful countries including the United States, China, and India have less administrative influence than you might think. Investigative journalist, Michael Blanding, has done interesting work on who pays the UN’s bills and what they get for it. Even more recently a hard-hitting study from Harvard’s s Eric Werker, and Dartmouth’s Paul Novosad, show that powerful countries including the United States, China, and India have less administrative influence, while small but rich democracies such as Finland and New Zealand are overrepresented. For those who believe that the UN has real influence on the world by setting rules and norms between nations, many feel that the country who pays the piper must name the tune, and this is not happening.

For those who believe that despite all these apparent superpowers, the UN merely reflects the agendas of the states within it, they may take a more laissez-faire attitude to the UN budget. Either way, the national makeup of senior positions that run the UN can tell us a lot about which countries are actually calling the shots in world affairs. “Even if you think the UN is merely reflecting the world order instead of creating it, you should still know who is running it,” says Werker.

Decision-making at the UN

Although the UN Secretariat, the executive arm of the organization, has some 43,000 employees worldwide, most of the strategic decisions are made by 80 or so senior members. Headed by the Secretary-General, the Secretariat plays key roles in agenda-setting for various deliberative UN organizations and manages global peacekeeping and humanitarian operations – including the UN’s emergency response. There is keen competition and string pulling among nations to win those upper-level staff appointments. While staff, in theory, are supposed surrender national allegiance at the door, in practice that is not the case, says Werker. “Both the UN’s own analysis and remarks by diplomats over the decades have indicated nations really do act in their own national interest.”

By looking at the national composition of Secretariat staffing over the years, Werker hypothesized that it is possible to show the changing nature of world power, providing a better way to measure international influence than traditional measures such as military prowess. “War, thankfully, is a very rare event,” he says. “When two countries do go to war, it means that one of them has miscalculated. By contrast, in this setting you have a constant struggle in real time between every nation in the world vying for influence within the Secretariat.” One might call this “diplomatic war”. To figure out who had been winning that competition, Werker and his colleague at Dartmouth (Prof Novosad) consulted the Yearbook of the United Nations. They constructed a database of every senior official in the Secretariat from 1945 to 2008—some 4,000 names in all. Then, consulting news reports and international directories, they determined the nationality of each of those officials.

Finally, Werker and Novosad compared the percentage of officials from each country to the percentage of that country’s population to determine the amount to which a nation was overrepresented in the Secretariat, “who was punching above their weight,” says Werker. A small number of demographically similar countries came out on top- namely the small, the rich, and the Nordic. “We found a handful of smaller, richer, democracies most represented by this metric, including Sweden, Norway, and Finland,” he says. Rounding out the top five were two other small, rich, democracies — New Zealand and Ireland. In the top 10 also appeared Denmark and Switzerland, along with Panama, Jamaica, and Uruguay. Werker was not surprised about the over-representation of Scandinavian countries, given their high rankings for education and low rankings for corruption. “The mandate of the UN on staffing is supposed to rest on three things: competence, integrity, and the third being national representation,” Werker says.

Even when controlling the first two measures, the top countries shared other characteristics. Chief among them were willingness to make investments in international diplomacy – both in terms of their number of consulates and embassies and the amount of money they put in diplomatic efforts. While military spending also correlated with influence in early UN history, it has been less of an indicator in more recent years, says Werker. Instead, the countries that seem to be overrepresented reflect a kind of (mainly) Scandinavian “soft power,” more adept at working behind the scenes in international institutions. As for the US, even though it still represents the largest country in terms of actual representation, its UN-related influence has steadily waned relative to population. At least until the 1980s, that did not seem to matter, says Werker, since its voting record matched that of allies that maintained high degrees of representation. In the past 35 years, however, the US has diverged from positions of its allies, leading to a decline in its relative power within the organization.

The most surprising finding of the Werker/Novosad survey is the degree to which burgeoning economic powers such as Brazil, India, and China, have remained underrepresented in the Secretariat—ranking 83, 89, and 95 respectively. “You can look at this in two ways,” says Werker. “Either despite being a military and economic power, these countries haven’t yet been able to project soft power. Or you can take another view, that these countries are rejecting the global system. Either way, it’s not clear that it’s in the best interest of the world for these rising powers to take a back seat when it comes to solving international conflicts.” Then again, says Werker, it took Germany and Japan many years after World War II to reach higher levels of representation, and both countries still lag compared to other G8 countries such as the United Kingdom, France, and Canada.

The Increasing Role of China at the UN

In the words of Bob Dylan, “the times they are a changing”. It is surely only a matter of time before the world order in the UN begins to reflect the new world order on the ground. Then we have another worry that we might air, as we have identified so many noisy elephants in this room. There are some who believe China is quietly and not always so quietly Remaking the UN In Its Own Image. Now it is well understood that any country using the UN as a tool for achieving hegemonic ambition could weaken the UN from within. Nevertheless, literature on China’s role at the UN has become increasingly critical of this P5 member.

The optimism of neoliberalism has been challenged by rising concerns about China playing a more active role in the UN and its specialized agencies. Currently, four of the 15 UN specialized agencies are headed by Chinese nationals, including the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDP), and the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). And with its contribution rising to 12 percent of the UN regular budget, passing Japan at 8.5 percent, China is currently the second-largest monetary contributor to the UN.

China’s greater UN leadership role has triggered the suspicion that it might take advantage to transform the organizations in ways that fit its interests. The suspicion about China’s expanding role in the UN may be reinforced by recent development postures. Beijing has been assimilating its grand geopolitical agenda, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) into the United Nation Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs), appeasing critics of its human rights record, providing monetary incentives to secure the support of other member states, and bringing more of its nationals into the UN.

Putting it bluntly, there is evidence of China’s growing influence in the UN System. Apologists could portray this merely as “catch up” but there are a few striking matters. Since 2007, the position of under-secretary-general for the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) has consistently been held by Chinese career diplomats, giving the Chinese government opportunities to reshape the UN’s development programs. According to the Center for a New American Security (CNAS), China has been promoting its BRI under the guise of SDGs. Liu Zhenmin, the incumbent head of DESA, openly claimed that the BRI serves the objectives of the SDGs at a high-level symposium. DESA also endorsed the China-funded program, “Jointly Building Belt and Road towards SDGs,” approving the BRI’s effect on achieving the Goals. Moreover, UN Secretary General António Guterres, assured that the UN system stands ready with Beijing to achieve the SDGs at the 2017 Belt and Road Forum. One must acknowledge the undoubted progress which China’s efforts are making in “lifting people from poverty”, but we may also have to look a little more cautiously?

Although the UN ostensibly welcomes China’s efforts under the BRI and looks forward to its achievements in the SDGs, what should be noted is that the BRI was never meant to be purely an international development plan. Another concern regarding China’s growing influence in the UN is that Beijing has been pressuring the latter to limit human rights groups’ participation. For instance, it has been claimed that Mr. Dolkun Isa, president of the World Uyghur Congress, was hindered from attending the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues by the incumbent head of DESA. Even as an ever-increasing number of news reports reveals the humanitarian crisis in Xinjiang, including physical torture and cultural genocide, China continues to downplay its policy while arguing that its “re-education measures” render Xinjiang a safer place. Moreover, China has sometimes stalled the UN Human Rights Council by appealing to Saudi Arabia, Algeria, and Russia to offer China votes.

It could also be argued that China has lobbied hard for leadership in the UN. Prior to the election of the ninth director-general of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in 2019, China slashed $78 million in debt owed by the Cameroon whose nominated candidate coincidentally withdrew his bid afterward. Meanwhile, China failed to contain an outbreak of the African Swine Fever, threatening global food security by causing international transmission across Asia and Europe. Nevertheless, Qu Dongyu, the Chinese candidate, was later elected as the first Chinese national to hold the post — regardless of the electoral controversy and the PRC’s own food security crisis.

With its leadership in four of the 15 UN specialized agencies and numerous subsidiary offices led by Chinese senior officials, Chinese leadership in the UN has been increasingly prominent. This is also reflected in the refusal of Taiwan’s attendance at the WHO and ICAO annual conferences, leaving the country’s leaders blocked from international cooperation. Ironically, international media look to Taiwan’s model of disease control as the country successfully prevented mass infection despite being one of the first to report confirmed cases. The WHO response is ambiguous. Secretary General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, for instance, praised China and downplayed Covid’s severity until it turned into a pandemic. It is argued by some that Tedros’ reluctance to criticize China have damaged the WHO’s professional standing.

China’s latest bid in the UN was to nominate Wang Binying as its candidate for the director-general election of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). China’s ambition backfired as state violation of property rights provoked considerable alarm about its control over the organization behind international property rights regulations. The growing concern prompted the United States to act, and led to the victory of Daren Tang, the Singaporean candidate backed by the U.S. But as five other UN agencies are scheduled for a change in leadership, we will see more leadership bids from China. When the member states voted in favor of the People’s Republic of China’s membership in the UN in 1971, one of the prevalent arguments was that a country with a population of more than 1 billion should not be left out. The sooner China was included into the international community, the earlier it would learn to play along with international norms, the argument went. Unfortunately, some analysts believe that China’s current measures indicate this was over-optimistic.

Although China’s collaborative behavior in the UN appears to be a role model for emerging states, some analysts suggest it may cut against international cooperation. For the system to work, all stakeholders must be trustworthy. Major powers must be willing to yield short-term gains for the purpose of increasing the incentives of long-term cooperation. For instance, the US and Japan have been top contributors to UN development projects, even though, as developed countries, they would not directly benefit from these projects. The cornerstones of building a trustworthy partnership are professionalism and impartiality. In over 75 years of history, the UN’s mandate has been respected by its members owing to its operations being carried out by a group of international civil servants sworn to uphold administrative neutrality, and whose judgments are founded on professional practice and the collective good of the international community. Some argue this “gentleman’s agreement” now appears under threat. Impartiality, justice, and universalism are the core values of the UN system. To that extent experts such as Tung Cheng-Chia and Alan Yang are justified in raising concerns about China. An opinion piece in a recent edition of the Wall Street Journal lament, “China Is Taking Over International Organizations, One Vote at a Time”. It further claims, “China’s decadelong campaign for empowerment at the UN is now helping shield Beijing from international scrutiny”. When China curtailed political freedoms in Hong Kong, rival declarations circulated at the Human Rights Council. One, drafted by Cuba and commending Beijing’s move, won the backing of 53 nations. Another, issued by the U.K. and expressing concern, secured only 27 supporters. While we must distinguish between regional rivalry and political rhetoric, it is particularly important that all P5 members set a tone of mutual co-operation in every aspect of UN governance.

The Russian Federation and Ukraine

Finally, we come to one of the greatest international crises to face the UN since WW2. Calling for de-escalation of tensions along the borders between Ukraine and the Russian Federation, the UN political affairs chief told the Security Council 31 January 2022 that any military intervention by one country in another would be against international law and the Charter of the United Nations, as Moscow denied any intention of launching a war on that neighboring State. “The Secretary-General has made clear that there can be no alternative to diplomacy and dialogue,” said Rosemary DiCarlo, USG for Political and Peacebuilding Affairs, during a public meeting of the 15-member organ. As of the end of February, and despite the direct protestations of the UNSG, Russia had further invaded Ukraine, and large-scale war had returned to Europe.

China’s representative said that the claim by the US that this will lead to war is unfounded, given the Russian Federation’s declaration that it has no plans to launch military action. War almost immediately followed. As of 24 February, the UNSG announced, “We are providing lifesaving humanitarian relief to people in need, regardless of who or where they are. The protection of civilians must be priority number one. International humanitarian and human rights law must be upheld. The decisions of the coming days will shape our world and directly affect the lives of millions upon millions of people….” This action by a P5, and current chairholder of the UNSG raises a fresh set of unfathomable questions of geo-politics and geo-economics.

Conclusion

As the Trump administration stepped back from many parts of the multilateral order established after World War II, it could be argued that China has emerged a chief beneficiary. The recent actions of the Russian Federation show an egregious lack of respect for the Charter. So, we return to the question at the top of our page, should geo-politics or geo-economics win? Should those who pay the piper get the power? To answer that question, we must be aware that even in geo-economics there are so many ways to pay? What does paying mean anyhow? In the first historic UN peacekeeping operations we would have measures this primarily in the deaths of nationals in the service of the UN in foreign fields. And those deaths are never a source of national popularity. On the other hand, does he who pays for the multi-million drone or robot pay just as much as the soldier who dies in the peace-keeping crossfire? So, our conclusion must be that the world is not so simple nowadays that we can neatly talk about “who pays.” These are pertinent questions also for NATO.

The UN has a perfect right to expect the highest level of integrity from all its members, and especially from the P5. For that reason, all the following headlines must be a source of regret to the UN system, and encouragement to all parties for improvement. These headlines are not meant to be exhaustive. Under President Trump America rocked from crisis to crisis, keeping American diplomats at the UN working in constant over-drive. As a P5 Britain’s “best day at the diplomatic office” is scarcely the imbroglio about the status of the Chagos Islands. For France, a decisive moment about the travails of being a P5 member came with the submarines wrangle with Australia, America and the UK. Russia is at this moment flagrantly violating international law in the Ukraine. For China, it is hard to judge whether territorial aggrandizement in the Asia-Pacific theatre, and saber-rattling about Taiwan, is the least becoming of a P5, trusted to maintain the diplomatic order. Our selections of news stories for all the P5 were random and far from comprehensive. When that authorized UN flag was proudly hoisted for the first time on 21 October on 1947, everyone certainly expected more.

As for those little powerful votes from tiny island nations of just a few thousand souls. Well, the UN has yet to find a way of addressing that inherent imbalance in geo-politics and geo-economy and is not likely to do so any time soon. The final thing we must remember about the UN is that the entire organization is constantly firefighting. That does not leave much scope for long-term planning. We are back to our friend the plumber. When he inspects the creaky old fabric of the UN organogram, he is very fearful of where he might put his spanner. That sometimes leaves the weak strong and the strong surprisingly weak. In places, it sustains inequality in who pays and how they pay. In the words of Peter Zeigan it is an invitation for a Disunited UN and a geo-politics of Dis-united maps. And as we go back to our idiom about who pays the piper, whoever thought “United Nations” was an accurate name for a global organization formed after the bloodiest of wars? It may well be better to affix an “out of order” sign to show that the organization is still only a work in progress. I am reminded of the wonderful quote from Kofi Annan during his time as UNSG:

The [UN Security Council] P5 ought to be dissuaded from using their veto power, which can paralyze the United Nations. The country blocking action ought to have to explain its decision and propose an alternative solution. It has been suggested that a veto only becomes effective if the vetoing state has the support of two or three other permanent members….

One can hope that this wonderful organization, in Ralph Bunche’s words, “our one great hope for a peaceful and free world…” may yet have the space to fulfill its potential. Another great UN diplomat, Brian Urquhart, once said that in the UNSC “there were no saints, only gradations of sin…” and one hopes this caveat from one of the organization’s most respected leaders, absolves me from any apparent criticism of any individual member state. Nothing could be further from my intention, which is to suggest that we are all prisoners of a UN system which arose at short notice in response to desperate times, and it is regrettable that the system has been so busily engaged ever since, that it has been quite impossible to really get fully under the bonnet of the UN and see how it may best be genuinely reformed in the future. The crisis facing the UN as evidenced by Ukraine, is the single greatest threat to global security since its formation.

Bibliography

Robert Adolph, 2019, Surviving the United Nations, New Academia, Washington DC.

Michael Barnett, 2003, Eyewitness to a Genocide: The United Nations and Rwanda, Cornell University Press, New York

David L. Bosco, 2009, Five to Rule Them All: The UN Security Council and the Making of the Modern World, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Kenneth Cain, 2011, Emergency Sex, Ebury Digital, New York.

Council on Foreign Relations, 2021, Funding the United Nations: What Impact Do U.S. Contributions Have on UN Agencies and Programs? Washington DC

Fred Eckhard, 2015, Kofi Annan, Ruder Finn Publisher, New York.

Sebastian Von Einsiedel, 2015, The UN Security Council in the 21st Century, Blackwell’s, Oxford.

Linda Fasulo, 2009, An Insider’s Guide to the UN, Yale University Press, New Haven.

Nikki R. Haley, 2018, With All Due Respect: Defending America with Grit and Grace, St Martin’s Press, New York

Roger Lipsey, 2020, Politics and Conscience: Dag Hammarskjöld on the Art of Ethical Leadership, SPI, New York.

Vaughan Lowe, 2010, The United Nations Security Council and War: The Evolution of Thought and Practice Since 1945, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Samantha Power, 2009, Chasing the Flame, Penguin Books Ltd.

Volker Rittberger, 2001, Global Governance and the United Nations System, United Nations University, Tokyo.

Pedro Sanjuan, 2005, The UN Gang: A Memoir of Incompetence, Corruption, Espionage, Anti-Semitism and Islamic Extremism at the UN Secretariat, Random House, New York

Michael Soussan, 2008, Backstabbing for Beginners: My Crash Course in International Diplomacy, Bold Type Books, New York.

James Traub, 2007, The Best Intentions: Kofi Annan and the UN in the Era of American World Power, Bloomsbury Publishing, New York

Peter Zeihan, 2020, Disunited Nations: The Scramble for Power in an Ungoverned World, Harper Collins, New York.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The United Nations’ COVID-19 Dilemmas: Towards a Budgetary Crisis?

- With Great Power Comes Great Climate Responsibility

- The United Nations and Middle Eastern Security

- Sri Lanka’s Economic Crisis: The Chinese Model in Operation

- The United Nations and Self-Determination in the Case of East Timor

- Can the United Nations Deepen Mediation Effectiveness in Libya?