Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will lead to a revival of realism in international relations discourse with an emphasis on power politics and inter-state conflict. However, it should also reaffirm the need to understand the psychology of political leaders and a key component of this is legacy. While Putin’s efforts to reinstate a so-called Russian sphere of influence can be framed within structural realist conceptions on the balance of power, this state-centric, materialist, unitary rational actor theory provides an insufficient explanation of his actions, which have inflicted significant economic, military and social costs on the Russian state, with limited material gain (Waltz, 1979). Rather, it comes down to the more intangible issue of cementing Putin’s status and legacy.

The role of status is well-recognised in IR debates (Götz, 2021). Notably, the theory of status dissatisfaction holds relevance in the context of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine by noting that states initiate conflict when there is a mismatch between the status a state believes it deserves and the status that others confer upon it (Renshon, 2017). However, this rational-instrumentalist approach is largely based on material capabilities rather than ideational considerations, such as historical and cultural context, which is key in understanding Putin’s quest to re-create a so-called ‘New Russia’ (Novorossiya) / ‘Russian world’ (Russky Mir) (Kolesnikov, 2015). Moreover, it fails to account for why states seek to achieve status through conflict as opposed to lower risk non-military actions. In this context, it is important to understand the role of the legacy in the decision-making of political leaders.

Legacy considerations are most prominent in autocratic states where leaders face limited checks and balances on their rule and start believing their own hype and hubris, particularly when it is combined with a belief that they alone can correct historical injustices that have been committed against the Motherland. Legacy considerations often gain momentum in the latter years of a political leader’s rule when they have consolidated power at home and it can become particularly pronounced towards the end of their tenure.

This explains Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, which comes over two decades after Vladimir Putin assumed power. Although Putin has amended the constitution so he can conceivably stay in power until 2036, he will turn 70 this year and there has also been speculation about his health (Neuman, 2020; Reynolds, 2022). While the launch of Russia’s military action against Ukraine caught many by surprise, this should not necessarily have been the case when framed in the context of Putin’s worldview that sees the disintegration of the Soviet Union as the ‘greatest geopolitical catastrophe’ of the 20th century, which has fuelled efforts to push back NATO expansion and so-called Western-sponsored colour revolutions in its near abroad (Associated Press, 2005). This explains Russian intervention in Georgia in 2008, recurring interventions in the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh, the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and subsequent interventions in the Donbas region, and the military deployment to Kazakhstan following anti-government unrest there in January 2022 (Umarov, 2022). In this context, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 can almost be seen as a forgone conclusion.

To be sure, legacy considerations can also be applied to democratic states with long-ruling leaders, particularly where they face weak opposition (although their actions typically fall short of war given the constraints imposed by their political systems). This is the case in India under the rule of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, which partially explains Modi’s decision to rescind the special status (Article 370) of Kashmir in 2019 (BBC, 2019). It was also relevant in Japan under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe with his concerted (but ultimately failed) effort to push for a resolution of the longstanding territorial dispute with Russia over the Northern Territories/ Southern Kuril islands (Banyan, 2019). While political ideology (such as the Hindu nationalist agenda of India’s ruling BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party)) and personal experience (such as Shinzo Abe following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather in seeking to resolve the territorial dispute with Russia) may be the direct triggers for these actions, it ultimately comes down to the issue of cementing legacy for these political leaders (Banyan, 2019).

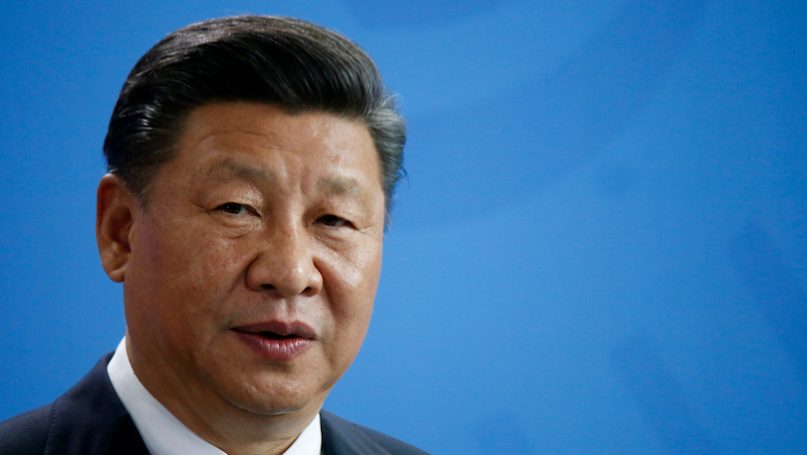

Focussing on China’s approach towards Taiwan, recent developments have triggered a flurry of analysis that seeks to draw parallels between Russia/ Ukraine and China/ Taiwan (Mizokami, 2022). However, it is important to recognise that China is not Russia and Taiwan is not Ukraine (Scobell and Stevensen-Yang, 2022). It remains unlikely that Beijing will seek to invade Taiwan over the short-term (notwithstanding the persistent risk of accidental escalation). Neither Beijing nor Washington, DC is seeking an intentional escalation of tensions in the Taiwan Strait. The Chinese government does not want to “rock the boat” in this crucial year for China’s domestic politics when Xi Jinping will continue to rule for an unprecedented third term following the 20th Party Congress. There may of course be a surge in political rhetoric and military posturing as Xi seeks to reaffirm his nationalist credentials, which explains the string of Chinese military exercises in the Strait and incursions into Taiwan’s Air Defence Identification Zone (Davidson, 2022).

On the part of Washington, DC, the United States maintains a far more long-standing and robust commitment to the defence of Taiwan than towards Ukraine. Beyond legislative commitments (embedded in the Taiwan Relations Act, Three Communiqués and Six Assurances), Taiwan’s significance lies in its strategic importance rooted in its geo-strategic position along the first island-chain and crucial role for global technology (particularly semiconductor) supply-chains (Lawrence, 2020; Crawford, Dillard, Fouquet, and Reynolds, 2021). This also explains why concerns about the US commitment to alliance partners in the Indo-Pacific following the withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021 were overly alarmist (Dean, 2021).

However, over the longer term the risk of conflict and forced re-unification will increase amid the growing importance of legacy considerations by President Xi Jinping. As noted by the third history resolution (adopted at the sixth plenary session of the 19th Central Committee in November 2021), Xi sees his primary contribution to make China “strong” (after China “stood up” under Mao Zedong and “became rich” under Deng Xiaoping) (Nikkei Asia, 2021). A key component of this is regaining so-called lost territories, including Taiwan. A key deadline for achieving this is 2035 when China aims to become a “modern socialist nation” (ahead of the “great revival of the Chinese nation” by 2049 – the centenary of the People’s Republic of China) (The Economist, 2021). Moreover, with the removal of presidential term limits following constitutional revisions in 2018, Xi could conceivably remain in power until 2035, when he will be 82 years old (BBC, 2018). As he approaches the end of his tenure, legacy considerations will gain prominence in foreign policy decision-making, which will fuel more aggressive behaviour towards Taiwan.

In terms of the exact nature of this behaviour, the regional and global balance of power will dictate China’s specific actions toward Taiwan. On the one hand, the persistence of a robust US-led alliance system in Asia will prompt Beijing to take a more nuanced approach in line with recent ‘grey zone’ tactics in the South China Sea and along the China-India border (Layton, 2021). This entails securing victories without firing a shot or through incremental advances employing both military and non-military tools (such as cyber/ information warfare, fishing/ oil survey vessels, and legal/ administrative actions). Possible scenarios include Beijing’s seizure of Taiwan’s offshore islands (Kinmen, Matsu and Taiwan-controlled disputed islands in the South China Sea – Pratas and Itu Aba), a naval blockade of Taiwan and continued efforts to squeeze Taiwan diplomatically (Dougherty, Matuschak, and Hunter, 2021; Brimelow, 2021).

On the other hand, a weak regional architecture that fails to challenge the emergence of a Sino-centric regional order will prompt a full-scale invasion of Taiwan, as well as efforts to reclaim other so-called “lost” territories. This will start with Beijing consolidating its hold over Hong Kong, Xinjiang and Tibet (which is already in progress), followed by more aggressive actions toward Taiwan, as well as territorial disputes in the South and East China Seas and along the India-China border (Bajpaee, 2019). In the extreme, an emboldened Chinese leadership fuelled by hyper-nationalism at home and a feeble international response could even be driven to extend its claims to other so-called “lost” territories ranging from Mongolia to parts of the Indochina sub-region and Korean Peninsula (Clark, 2018; Washburn, 2013).

For now, the robust international response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will make Beijing think twice about an overt military take-over of Taiwan. A string of visits by high-ranking US officials to Taiwan has reaffirmed Washington’s commitment to the defence of the island (Lai, 2022). Even before Russia’s most recent military actions in Ukraine, several Asian powers, including Japan and Australia were also becoming more vocal in their commitment towards Taiwan (Liff, 2021; Greber, Smith and Tillet, 2021). This has turned a largely bilateral dispute between the United States and China into a more complex multilateral issue (to the chagrin of Beijing). Moreover, the challenges facing the Russian military in the face of stiff Ukrainian resistance has been a wake-up call for both Beijing and Taipei; a signal to the latter that it can put up a credible fight against a much stronger adversary, and a signal to the former that taking Taiwan will not be straightforward despite its military superiority.

However, there should be no doubts that Xi will not allow the ‘Taiwan question’ go unanswered indefinitely. While the Western response to Russia’s actions have demonstrated the unity and resolve of NATO, from Beijing’s perspective it has also served to demonstrate the impotence of the organisation in failing to prevent the conflict in the first place. A blurring of the United States’ longstanding position of ‘strategic ambiguity’, with calls by some to shift towards a position of ‘strategic clarity’ as part of more explicit US support for Taiwan may even accelerate Beijing’s timetable on the takeover of Taiwan (Forgey and Ward, 2021). As the balance of power in the Taiwan Strait and broader Indo-Pacific continues to lean in China’s favour and as Beijing approaches key political milestones in 2035/ 2049, efforts to resolve the Taiwan issue will gain momentum. Legacy considerations will be a key driver of this, particularly as Xi approaches the end of his term.

To conclude, neorealist conceptions on the balance of power may dictate why Russia has decided to invade Ukraine or why China will eventually seek to annex Taiwan. However, this largely discounts the role of human agency, including the nature of the political system and psychology of political leaders (although this is partially addressed in classical realist approaches that locate causation in human agency (Morganthau, 1956; Barkin, 2003)). Legacy considerations offer a means to bridge the gap by providing a key indicator of when and how states will seek to assert themselves.

Status is particularly relevant in autocratic states led by rulers with revisionist agendas and historical grievances. This effort to correct past injustices includes Putin’s quest to redress the disintegration of the Soviet Union and push back on NATO expansion and Xi’s focus on the ‘Century of Humiliation’ and efforts to revive some semblance of the pre-Westphalian Sino-centric tribute system in Asia (Harper, 2019; Kang in Beeson and Stubbs, 2012; Fairbank, 1967). This is fuelling a new form of Lebensraum (‘living space’) by both countries. While currently focussed on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Xi’s efforts to reinstate a Sino-centric regional order by recovering ‘lost lands’, including Taiwan should not be overlooked.

References

Associated Press. (2005) ‘Putin: Soviet collapse a ‘genuine tragedy”. NBC News. 25 April. https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna7632057.

Banyan (2019) ‘Why Japan’s prime minister pines for four desolate islands’ The Economist. 9 February. https://www.economist.com/asia/2019/02/07/why-japans-prime-minister-pines-for-four-desolate-islands.

Bajpaee, C. (2019). ‘New Normal in Sino-Indian Ties’. War on the Rocks. 21 April. https://warontherocks.com/2021/04/china-and-india-de-escalation-signals-new-normal-rather-than-a-return-to-the-status-quo/.

Barkin, S. (2003). ‘Realist Constructivism’. International Studies Review. Vol. 5, Issue 3. September. pp.325-342.

BBC. (2018). ‘China’s Xi allowed to remain ‘president for life’ as term limits removed’. 11 March. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-43361276.

Brimlow, B. (2021). ‘An invasion isn’t the only threat from China that Taiwan and the US have to worry about’. Insider. 16 June. https://www.businessinsider.com/taiwan-and-us-also-face-risk-of-china-blockading-taiwan-2021-6?r=US&IR=T.

Clark II, K.A. (2018). ‘Imagined Territory: The Republic of China’s 1955 Veto of Mongolian Membership in the United Nations’. The Journal of America-East Asian Relations. Vol. 25, No. 3. pp.263-295.

Crawford, A. Dillard, J. Fouquet, H. and Reynolds, I. (2021) ‘The World in Dangerously Dependent on Taiwan for Semiconductors’. Bloomberg. 25 January. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2021-01-25/the-world-is-dangerously-dependent-on-taiwan-for-semiconductors.

Davidson H. (2022) ‘China sends largest incursion of warplanes into Taiwan defence zone since October’. The Guardian. 24 January. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jan/24/china-sends-largest-incursion-of-warplanes-into-taiwan-defence-zone-since-october.

Dean, P. J. (2021). ‘Why the tragic Afghanistan withdrawal should reassure US allies in Asia’. New Atlanticist. 30 August. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/why-the-tragic-afghanistan-withdrawal-should-reassure-us-allies-in-asia/.

Dougherty, C. Matuschak, J. and Hunter, R. (2021). The Poison Frog Strategy: Prevent a Chinese Fait Accompli Against Taiwanese Islands. October. Washington, DC: Center for a New American Security.

Fairbank, J.K. (1967). The Chinese World Order (Harvard: Harvard University Press).

Forgey, Q. and Ward, A. (2021). ‘Lawmakers: End ‘strategic ambiguity’ towards Taiwan’. Politico: National Security Daily. 7 October.

Götz, E. (2021). ‘Status Matters in World Politics’. International Studies Review. Vol. 23, Issue 1. March. pp.228-247

Greber, J., Smith, M. and Tillett, A. (2021). ‘Canberra prepares for Taiwan conflict as tensions escalate’. Financial Review. 16 April. https://www.afr.com/world/asia/canberra-prepares-for-taiwan-conflict-as-tensions-escalate-20210416-p57jqv.

Harper, T. (2019). ‘How the Century of Humiliation Influences China’s Ambitions Today’. Imperial & Global Forum. Centre for Imperial and Global History, University of Exeter. 11 July. https://imperialglobalexeter.com/2019/07/11/how-the-century-of-humiliation-influences-chinas-ambitions-today/.

Kang, D. (2012). ‘East Asia when China was at the centre: the tribute system in early modern East Asia’. Beeson, M and Stubbs, R. Routledge Handbook of Asian Regionalism (New York: Routledge).

Kolesnikov, A. (2015) ‘Why the Kremlin is Shutting Down the Novorossiya Project’. Eurasia in Transition. Carnegie Moscow Center

Lai, J. (2022). ‘Former top US defense officials visit Taiwan amid tensions’. Associated Press. 1 March. https://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory/top-us-defense-officials-visit-taiwan-amid-tension-83171385.

Lawrence, S.V. (2020). ‘President Reagan’s Six Assurances to Taiwan’. Congressional Research Service: In Focus. 8 October. IF11665.

Layton, P. (2021). China’s Enduring Grey-Zone Challenge. Canberra: Air and Space Power Centre.

Liff, A.P. (2021). ‘Has Japan’s policy toward the Taiwan Strait changed?’ Order from Chaos. 23 August. Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/08/23/has-japans-policy-toward-the-taiwan-strait-changed/.

Mizokami, K. (2022). ‘With the World’s Attention on Ukraine, Could China Turn and Invade Taiwan?’ Popular Mechanics. 25 February. https://www.popularmechanics.com/military/a39209668/russia-ukraine-impact-on-taiwan-china/.

Morganthau, H. (1948) Politics Among Nations. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Neuman, S. (2020) ‘Referendum In Russia Passes, Allowing Putin To Remain President Until 2036’. National Public Radio. 1 July, https://www.npr.org/2020/07/01/886440694/referendum-in-russia-passes-allowing-putin-to-remain-president-until-2036?t=1646237212708.

Nikkei Asia. (2021). ‘Full text of the Chinese Communist Party’s new resolution on history’. 19 November. https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Full-text-of-the-Chinese-Communist-Party-s-new-resolution-on-history.

Renshon, J. (2017) Fighting for Status: Hierarchy and Conflict in World Politics. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

Reynolds, M. (2022). “Yes, He Would’: Fiona Hill on Putin and Nukes’ Politico. 28 February. https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/02/28/world-war-iii-already-there-00012340.

Scobell, A. and Stevensen-Yang, L. (2022). ‘China Is Not Russia. Taiwan is Not Ukraine’. United States Institute of Peace: Analysis and Commentary. 4 March. https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/03/china-not-russia-taiwan-not-ukraine.

The Economist (2021). ‘Xi Jinping is rewriting history to justify his rule for years to come’. 6 November. https://www.economist.com/china/2021/11/06/xi-jinping-is-rewriting-history-to-justify-his-rule-for-years-to-come.

Umarov, T. (2022) ‘Will Russia’s Intervention in Kazakhstan Come at a Price?’ Carnegie Moscow Center. 28 January. https://carnegiemoscow.org/commentary/86298.

Waltz, K. (1979) Theory of International Politics. United States: McGraw-Hill.

Washburn, T. (2013). ‘How an Ancient Kingdom Explains Today’s China-Korean Relations’. The Atlantic. 15 April. https://www.theatlantic.com/china/archive/2013/04/how-an-ancient-kingdom-explains-todays-china-korea-relations/274986/.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Beijing’s Weaponisation of Diplomacy Against Taiwan

- Opinion – Why Tsai Ing-wen’s Victory is a Blessing for the Taiwan Strait

- Opinion – Taiwan Could Be to China What Canada Is to the US

- Opinion – Taiwan’s Almighty Squeeze

- Great Power Competition in Ukraine Amidst the Emerging US-China Rivalry

- Opinion – Omens for US-Taiwan Relations in the Biden Administration