For a long time, unrestricted cross-border investments were seen as a source of economic prosperity, peace, and stability in Western liberal market economies (Rosecrance & Thompson, 2003, pp. 377-379). In the last decade, however, pro-liberal market forums have increasingly tightened their Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) screening practices on grounds of security and public order (Esplugues, 2018, pp. 440-443; Liu, 2020). This is particularly puzzling in the case of the European Union’s FDI Screening Regulation, which is an extraordinary measure given the EU’s mantra of market openness that is built into its liberal identity (Svoboda, 2020, p. 2). It is socially relevant to understand what caused the introduction of this extraordinary measure that harms the EU’s legitimacy as “one of the most open places to invest in the world” (EC, 2021).

Since the official policy proposal on 13 September 2017, the European Commission’s supporting argumentation is based on the storyline of changing foreign investment patterns that challenge the security of the Union and the Member States. It emphasises the increasing role of emerging economies – especially China – as providers of FDI and the decreasing FDI stock of traditional investment partners in Europe such as the United States (EC, 2017d, pp. 3-5). In the grand scheme of things, however, this threat seems to be relatively weak as the US dominated with 35.1% in comparison to China’s mere 0.9% in terms of FDI stock held in Europe in 2017 (Eurostat, 2019). It leads one to question: why Chinese FDI in Europe is perceived as more threatening than the cross-border investments of an advanced economy such as the US.

The existing literature explains the introduction of the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation by focusing on the material interests, namely the US-China Trade war, China’s intensified state capitalism, and the disintegrating forces of Chinese FDI on the European integration project (Defraigne, 2017; Paszak, 2017; Bickenbach & Liu, 2018; Roberts et al., 2019; Meunier & Nicolaidis, 2019; Riela & Zámborský, 2020). The overarching claim is that China’s strategic asset-seeking investments impose security challenges on Europe that led to the EU’s framework to screen FDI (Hooijmaaijers, 2019; Schill, 2019; Borowicz, 2020; Svoboda, 2020). These important findings, however, do not shed light on the ideational interests of the EU that are shaped by the ‘China Threat’ discourse. According to Buzan et al., presenting an issue as an existential threat, that is, securitisation can legitimise an extraordinary measure (1998, p. 26). This research project contributes to the academic debate by attending to the ideational instead of material dimension, and by analysing the ‘China Threat’ discourse that possibly legitimised the introduction of the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation.

The object of analysis is the European Commission (Commission) who speaks security to advocate for the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation as the official policy proposer. Following a constructivist epistemology, the purpose of this thesis is not to assess the validity of the physical threat, but to understand the linguistic construction of a shared understanding that Chinese FDI is an existential threat. Therefore, this thesis aims to answer the explanatory research question: Why did the European Union introduce the extraordinary measure of the Regulation (EU) 2019/452 that establishes a framework for the screening of Foreign Direct Investment into the Union?

Using the securitisation theory of the Copenhagen School (Buzan et al., 1998), I argue that the economic, military and political securitisation of Chinese FDI in Europe legitimised the enactment of the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation. The discourse analysis uncovers that the Commission presents the EU Single Market, the competitiveness of EU businesses, European workers, the EU’s strategic capabilities and public order, and the EU integration project as existentially threatened by China’s strategic investments in Europe. It also reveals how the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation is presented as the required tool for protection. Moreover, the findings demonstrate that the Commission’s arguments to protect the economic competitiveness of EU businesses and European workers are linked to military and political security arguments. This covers up the protectionist undertone of economic security arguments, which would be illegitimate in a liberal economic context such as the EU. This is a valuable contribution to the securitisation literature because it confirms Buzan et al.’s theoretical proposition that securitisation analysts have to consider non-economic arguments in economic threat discourse to comprehensively understand economic securitisation in a liberal economic context (1998, pp. 100-103).

This thesis is structured as follows. Chapter 2 reviews the literature on the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation. Chapter 3 continues with the analytical framework concerning the theory and the methodology. Chapter 4 examines whether and how the Commission securitises Chinese FDI in Europe. Concluding, chapter 5 answers the research question, reflects on the limitations of the analysis and the implications of the findings, and offers suggestions for future research.

State of the Art

As chapter 1 has set out the research problem, chapter 2 reviews the existing literature that explains the introduction of the Regulation (EU) 2019/452. From a macro-perspective, some scholars concentrate on the US-China trade war that shifted the international order away from liberal multilateralism, which, in turn, normalised FDI screening practices in liberal market forums (Roberts et al., 2019; Scholvin & Wigell, 2019; Aggarwal & Reddie, 2020; Borowicz, 2020). They put the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation in one basket with the tightening FDI screening practices of the US, Canada, Australia, and Japan as empirical examples of this phenomenon (Esplugues, 2018; Ishikawa, 2020; Heim & Ribberink, 2021; Santander & Vlassis, 2021). While this macro-perspective considers the beliefs and behavioural expectations that guide actor behaviour in the international system, it does not acknowledge the sui generis nature of the EU. The EU is not compatible with a nation-state or a superstate, because it is an international organisation with state-like features and multi-level governance (Moskvan, 2017, p. 242). Therefore, it is important to focus on the EU case specifically.

The academic debate about the causes of the introduction of the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation can be divided along the lines of the traditional IR theories. Applying a neorealist analytical lens, some scholars emphasise that China’s strategic investments and intensified state capitalism threaten the economic and military security of the EU Member States (Defraigne, 2017; Paszak, 2017; Hooijmaaijers, 2019; Schill, 2019; Riela & Zámborský, 2020; Svoboda, 2020; Lai, 2021). In the liberal institutionalist line of thought, however, Chinese FDI threatens the EU’s political security (Christiansen & Maher, 2017). Scholars in this camp suggest that the crisis of the liberal international order and the disintegrating forces of Chinese direct investment in the EU integration projects are the explanatory factors (Nicolas, 2014; Meunier, 2014b; Casarini, 2015; Bickenbach & Liu, 2018; Simon, 2020). However, Meunier has gone furthest as her early work addresses how Chinese FDI threatens the EU’s unity regarding the cacophony of national FDI rules and the competition amongst the EU Member States (Meunier, 2014a; Meunier, 2014c; Meunier et al., 2014). Her later work analyses how the hostile public opinion towards China in the Member States fostered EU integration on FDI policy (Meunier, 2019; Chan & Meunier, 2020; Meunier & Mickus, 2020). Meunier and Nicolaidis suggest that the securitisation of Chinese direct investments in Europe led to the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation (2019, pp. 108-109). However, they focus on a cost-benefit analysis of economic interests that does not provide any empirical evidence that Chinese FDI is presented as an existential threat to the EU’s security by any actor, which is a gap that this thesis aims to bridge.

While the existing studies on the Regulation (EU) 2019/452 offer valuable insights on the material interests of the EU to screen FDI, these neglect the ideational interests. Their underlying assumption is that the ‘China threat’ to the EU’s military, economic and political security is an objective fact. From a social constructivist perspective, however, the idea of a ‘China threat’ is a social fact that only exists if actors accept it as such and act accordingly (Wendt, 1992, pp. 392-395). While the Chinese FDI influx in Europe may be a physical reality, it is only given meaning as being threatening based on a shared understanding. Therefore, it is important to understand how policy discourse constitutes such a shared understanding that legitimises the EU’s FDI screening framework.

A range of studies examines the ‘China threat’ discourse by academics and politicians in the West in general and in the US in particular (Pan, 2004; Jerdén, 2014; Song, 2015; Peters et al., 2021). Only Rogelja and Tsimonis (2020), however, focus on the EU as the geographical region for their research on the ‘China threat’ discourse. Using securitisation theory, they unpack how European think tanks present Chinese FDI in Europe as an existential threat to the EU’s political unity, identity, and strategic assets. While securitisation theory is their theoretical framework, they employ the post-structuralist instead of the social constructivist approach by concentrating on the power of language and othering practices instead of the normativity hidden in the language (Rogelja and Tsimonis, 2020, pp. 103-105). Moreover, think tanks do not have the legislative power of the European Commission, which makes the latter an important securitising actor that is still to be studied. In sum, the gap in the academic literature is a comprehensive analysis of the Commission’s policy discourse that securitises Chinese FDI, which, in turn, legitimises the introduction of the extraordinary measure of the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation. The next chapter sets out the analytical framework that helps this thesis to bridge this gap.

Analytical Framework

The Securitisation Theory of the Copenhagen School

This section explains why and how the securitisation theory of the Copenhagen School in IR helps to answer the research question. Securitisation theory enables gaining insights on “who can “do” or “speak” security successfully, on what issues, under what conditions, and with which effects” (Buzan et al., 1998, p. 27). It reveals how presenting an issue as an existential threat can legitimise extraordinary measures as urgent solutions (Balzacq et al., 2016, p. 495). In this thesis, the dependent variable is the introduction of the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation, which is an extraordinary measure considering the EU’s mantra of market openness. Securitisation theory helps to assess, whether and how the Commission securitises Chinese FDI, which is the explanatory variable.

Securitisation theory is split into the social constructivist and sociological branches. Both agree that presenting an issue as existentially threatening is a securitising move that only turns into successful securitisation if the audience accepts it as such. However, the disagreement centres around the conceptualisation of securitisation (Balzacq, 2011, pp. 1-3). The sociological branch considers securitisation as an intersubjective practice and analyses the audience’s response (Balzacq, 2005; Bigo & Tsoukala, 2008; Salter, 2011), whereas the social constructivist branch – the Copenhagen School – conceptualises securitisation as speech act, that is, the performative expression of information, that presents an issue as an existential threat. The analytical focus is on the actor who speaks security under the assumption that specific security rhetoric evokes the logic of survival that, in turn, induces audience acceptance. The Copenhagen School attends to the socio-political impact of discourse, which is written and spoken communication (Buzan et al., 1998, pp. 24-25; Waever, 2009, p. 22). This is more appropriate for this thesis that concentrates on whether and how the Commission’s securitising speech act legitimises the introduction of the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation.

Following the logic of the Copenhagen School, the central concepts are the securitising actor, the referent object, and the security sector. The securitising actor is the one who speaks security from a position of authority defined by social recognition and expertise (Buzan et al., 1998, p. 33). In this thesis, the object of analysis is the European Commission – represented by its President and the Directorate General (DG) Trade in the policy process of the Regulation (EU) 2019/452 – that takes upon the role as securitising actor for two reasons. Firstly, the Commission enjoys the authority as the exclusive policy proposer in FDI policy and the expertise of the Commission Services. Secondly, the Commission proposes the extraordinary measure unlike the reactive role of the MEPs and the Council via debate and voting as well as the opinion-giving role of the advisory committees. They can be seen as the audience because these reactive actors can influence the decision-making process of policy, but they do not construct the threat discourse (Buzan et al., 1998, p. 33).

Referent objects are things that the securitising actor portrays as existentially threatened and in need to be protected by the extraordinary measure (Buzan et al., 1998, p. 36). This does not mean a threat to the existence per se, but it can also be a threat to the “essential quality of existence” (ibid., p. 21, emphasis added). For example, strategic acquisitions of European firms in the high-tech sector can jeopardise the EU’s competitiveness through the outflow of technological know-how, which does not mean the end of its existence but an erosion of its quality of existence.

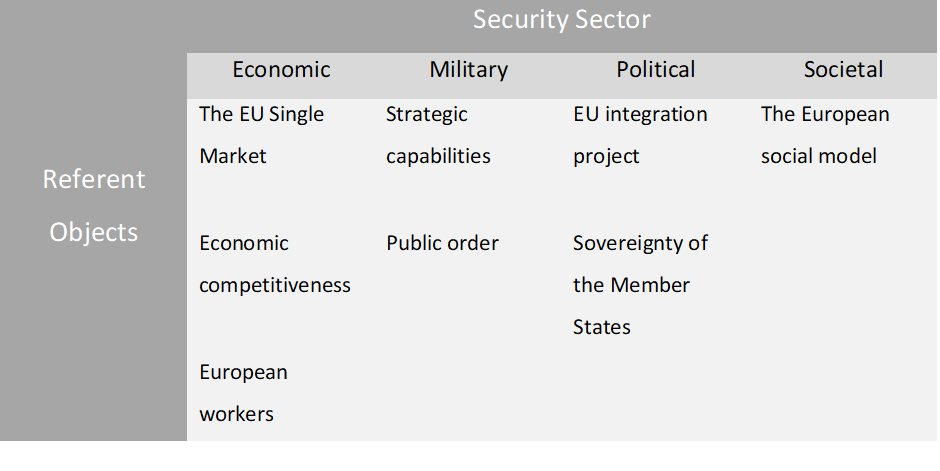

Each referent object belongs to a certain security sector (Buzan et al., 1998, pp. 36-40). The security sector is an analytical lens that identifies a type of securitising discourse based on the type of relationship and interaction between the actors involved (Floyd, 2019, p. 174). This is not to be confused with sectors in economic terms that indicate an area of economic productivity (p. 177). Inspired by the analytical framework developed by Buzan et al. (1998, pp. 179-188), this thesis has a deductive approach and employs four security sectors. Firstly, the economic security sector attends to arguments relating to finance, trade, and production. In the liberal economic context of the EU, liberal economic securitisation centres on protecting the free market (Buzan et al., 1998, p. 7). Therefore, the referent object ‘EU Single Market’ compromises the liberal economic rules that constitute the EU Single Market’s quality of existence (p. 106). The referent object ‘economic competitiveness’ concerns the position of EU business in the global market and the survival of European companies, whilst the ‘European workers’ refer to the jobs and income of European citizens.

Secondly, the military security sector focuses on the arguments about forceful coercion (Buzan et al., 1998, pp. 49-55). In this thesis, the military referent object ‘strategic capabilities’ compromises the strategic assets, critical technologies, and infrastructure in Europe, whilst the ‘public order’ referent object is the normal functioning of society. Thirdly, the political security sector focuses on interactions that relate to sovereignty and recognition. In the EU context, the recognition of the EU integration project and the sovereignty of Member States can be existentially threatened (Buzan et al., 1998, pp. 145-148). Fourthly, the societal security sector concentrates on arguments about collective identities. The European social model refers to the liberal values that are rooted in the EU’s post-war origins and political-legal constitution (p. 183). Table 1 below shows the codebook with the referent objects of each security sector for the analysis.

Buzan et al. suggest that the economic security sector is not a stand-alone analytical lens in a liberal economic context (1998, pp. 100-103). Except for the EU Single Market, economic referent objects do not have a legitimate claim to survival because liberals believe that economic governance should only protect the free market. Hence, it is likely that the securitising actor links the economic referent objects to other types of referent objects so that intellectually incoherent arguments are avoided (p. 106). For example, the securitising actor may argue that the EU’s economic competitiveness in the high-tech sector needs to be protected because it will also secure Europe’s critical technologies. The Copenhagen School suggests that solely looking at economic arguments is not sufficient to comprehensively understand economic securitisation in a liberal economic context (p. 116). The next section builds further on this theoretical proposition.

Case Selection

The motivation to examine the single-case study of the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation is twofold. Empirically, it is a unique case of the phenomenon of tightening FDI screening practices in liberal market forums during the last decade. The EU is an international organisation with state-like features (Moskvan, 2017, p. 242), which is incompatible with national governments. Theoretically, the securitisation of Chinese FDI in Europe is a most likely case, which tests the validity of the Copenhagen School’s theoretical proposition on economic securitisation (Buzan et al., 1998, pp. 100-103). This is questioned by Floyd, who uses an action-based approach to securitisation with process-tracing as the research method (2016, p. 688; 2019, p. 180). However, the Copenhagen School’s analytical framework based on discourse analysis is more appropriate for this research project that analyses policy discourse instead of its actions, hence, it tests the validity of the theoretical proposition.

Data Collection

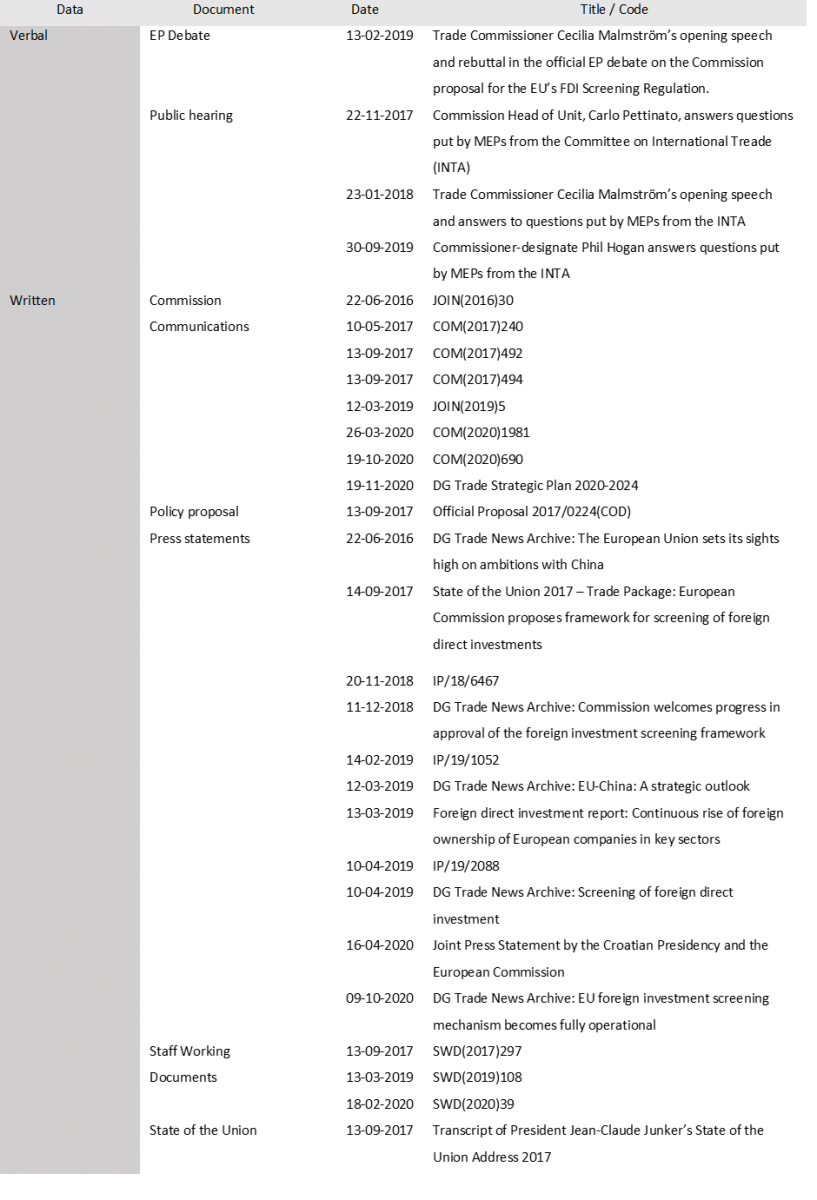

Written and verbal data were used in the analysis. I collected twenty-four written documents compromising the Commission’s policy proposal, Commission Communications (CC), Staff Working Documents (SWD), and press statements. The selection of different types of documents enhances the validity of the analysis. Salter warns that examining one type of data or document in a securitisation analysis is over simplistic and fails to comprehensively trace securitisation (2011, p. 117). The dataset does not include any meeting minutes of the Commission representatives during the trialogue phase of the Regulation (EU) 2019/452. This informal meeting period is behind closed doors, thus, such data is not accessible. Nevertheless, I triangulated the written data with verbal data, namely speeches held by the Commission President and the DG Trade representatives at the European Parliament. Therefore, the dataset sufficiently represents the Commission’s policy discourse on the ‘China threat’ and FDI screening. To enhance the transparency of the analysis and the reliability of the findings, Table 1 in the Appendix shows an overview of the dataset.

The primary data was collected via online research in the databases of the European Commission Documents Archive, EUR-Lex, and the European Parliament Multimedia Centre in April and May 2021. The EU’s claim to be transparent leads to the online publication of all press statements, formal communication, public hearings, and the EP debate (Watson, 2012, p. 283). This enabled access to all authentic data required for the analysis, and thus no copies or forged documents were analysed. I used the following key search terms: “FDI screening”, “direct investment screening”, “screening foreign investments”, “foreign direct investment”, “strategic investment”, “Chinese investment”, “FDI Regulation” and “China strategy”. The timeframe of the dataset begins with the Chinese FDI peak in Europe in 2016 and ends in 2020, when the Regulation (EU) 2019/452 became fully operational.

Method – Discourse Analysis

The conceptualisation of securitisation as speech act is inextricably bound up with discourse analysis as the research method. Discourse analysis draws attention to the co-constitutive relationship between language and societal norms that inform the interests and behaviour of actors. The analytical focus is not on the intention or motives of the speaker, but on the socio-political impact of one’s speech act (Stoffers, 2021, p. 14). This research project aims to uncover how speaking security legitimises an extraordinary measure, a socio-political impact of speech act, thus, discourse analysis is the most appropriate method. As discourse analysis is interpretative (Hardy et al., 2004, p. 21), I coded the primary data with the software programme ATLAS.ti to perform the analysis rigorously and systematically. Moreover, ATLAS.ti enables the online sharing of analytical choices, empirical findings, and research notes, which enhances the transparency and reliability of this research project.

To operationalise securitisation, the Copenhagen School argues that the indicator of securitisation is when an issue is presented as an existential threat. Hence, the criterion is that the speech act must illustrate which designated referent objects will be lost if the extraordinary measure is not enacted (Buzan et al., 1998, pp. 29-32). Waever stresses that only an existential threat, not just a threat, induces a sense of urgency and necessity – the logic of survival – of the audience that legitimises the extraordinary measure (2009, p. 22). The inducement of such logic is the so-called reality effect, which is how the social reality of the audience is shaped by the securitising actor. In addition to the socio-historical context, one must consider rhetorical mechanisms, such as figures of speech, binary distinctions, the specific use of pronouns, the repetition of words, and the storyline in the discourse that all together shape the audience’s worldview. Binary distinctions create a division between the protagonist, the leading character, and the antagonist, who works against the interests of the protagonist based on essentialist language (Stoffers, 2021, pp. 17-20). The subsequent chapter applies this operationalisation of the securitisation theory of the Copenhagen School to explain the introduction of the extraordinary measure of the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation.

Findings and Discussion

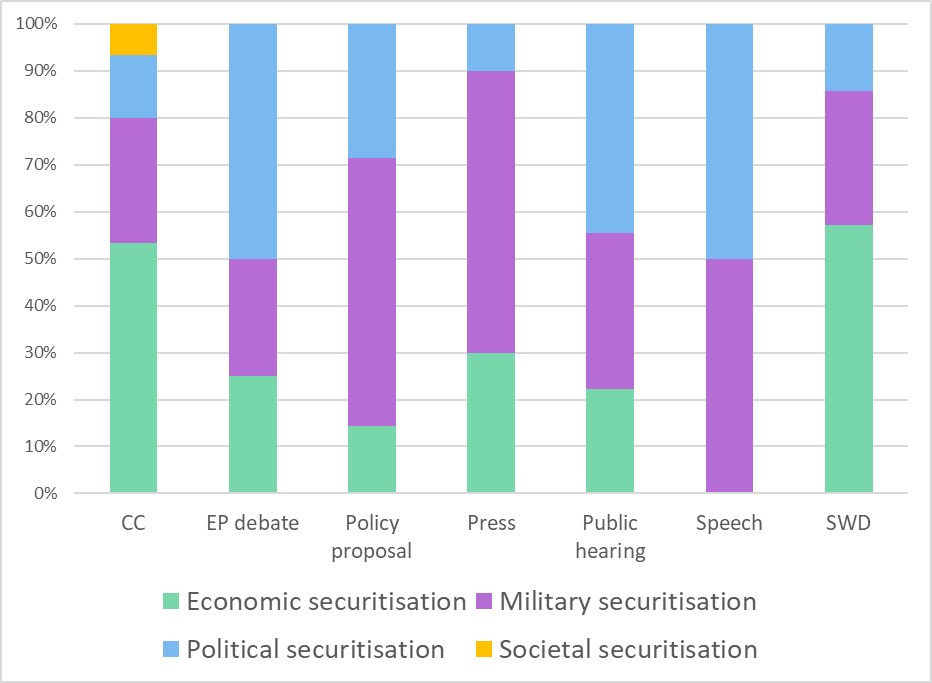

Having established the theory and methodology in chapter 3, it will now be possible to apply the analytical framework in chapter 4. In this discourse analysis, it is important to consider the differences in the securitising speech act across different formats of linguistic expression (Stoffers, 2021, p. 12). Figure 1 below shows an overview of the securitisation of Chinese FDI in the Commission’s discourse on the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation for each speech act format in the dataset.

The economic securitisation of Chinese FDI shows dominance in the Commission’s reports, namely the Commission Communications and Staff Working Documents. This format is appropriate for economic security arguments considering the length of these reports, which allows for deliberate securitising discourse with graphs and statistics that establish an economic undertone. The military securitisation of Chinese FDI reigns supreme in the policy proposal and the press statements, which can be explained by the former’s legal context and the latter’s pressure of public opinion. As the EU’s open market mantra is built into its political-legal constitution (Manners, 2002, p. 240), Bickenbach and Liu suggest that European policymakers and the public would only perceive the EU’s framework to screen FDI as legitimate if it is based on military security arguments (2018, p. 19). Political securitisation seems to be important in the Commission’s speeches, namely the public hearings, the EP debate, and the State of the Union in 2017. An explanation is that the format of political speeches allows for more emotional language and rhetorical mechanisms to express a sentiment of EU unity more than the other formats. While only the societal securitisation of Chinese FDI proves to be irrelevant, this seems to be outweighed by the other forms of securitisation. In sum, Figure 1 illustrates the prevalence of the economic, military, and political securitisation of Chinese FDI across all documents and speeches. The differences across discourse formats may suggest that the Commission considers which type of security rhetoric is more appropriate in which linguistic setting to legitimise the extraordinary measure of the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation.

The remainder of chapter 4 compromises four sections that systematically analyse whether and how each type of securitisation is present in the securitising actor’s discourse on the extraordinary measure. Each section considers the ‘China threat’ discourse, the relevance of the referent objects, and, if there are any, their discursive link to other security sectors. The latter is particularly important for the economic security sector analysis because it will confirm or reject Buzan et al.’s theoretical proposition (1998, pp. 100-103).

Economic Securitisation

The Commission’s economic threat discourse is based on the storyline about the changing foreign investment patterns that challenge the EU’s security. The ‘China threat’ idea is constructed by the binary distinction between the EU’s traditional investment partners – allies of the EU Single Market – and its emerging investment partners who are presented as strategic and not compliant with the EU’s economic rulebook (EC, 2017a, p. 15; EC, 2017d, pp. 3-5; EC, 2017e, p. 6). In a public hearing on 23 January 2018, for example, Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström states:

Traditionally, our investment partners have been countries with similar economic values as ours: using the same rulebook. However, global markets have changed and there are new powerful players emerging who do not always have the same standards, not always have the same rules, and who do not always play fair […] This is the background that we need to have when we talk about the Commission’s proposal on investment screening. (Malmström, 2018, January 23, 14:36:08).

The emphasis on playing fair via a rulebook and the tricolon of standards underline the idea that the unfair investment practices of emerging players are incompatible with the EU’s economic rulebook. According to Buzan et al., anything that unglues the liberal economic rules constituting the EU Single Market is an existential threat to this economic referent object (1998, p. 106). Hence, the idea of emerging powerful players who do not comply with the EU’s market rules is an existential threat to the EU Single Market. A closer look at the SWDs and the CCs, in which economic securitisation is the dominant security rhetoric, reveals that China is repeatedly singled out as the primary example of this existential threat to the EU Single Market. The DG Trade makes separate graphs for Chinese FDI and consistently repeats the word groups “China, for instance” (EC, 2017e, p. 3), “investors like China” (ECHR, 2019, p. 27), “with China standing out” (EC, 2019, p. 2). Taking all these discursive elements into account uncovers the normative association between Chinese direct investments in Europe and unfair investment practices that existentially threaten the EU Single Market.

However, a successful instance of securitisation is not complete without presenting the extraordinary measure as the required policy solution (Buzan et al., 1998, p. 32). The Commission presents the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation as a policy tool “to restore a level playing field” (EC, 2017a, p. 15), to “ensure that everyone plays by the same rules” (EC, 2017b, p. 2), whilst “adapting to a new global environment” (Malmström, 2018, January 23, 14:42:45). In other words, the Regulation would protect principles that guarantee the quality of existence of the EU Single Market. Therefore, it can be argued that the economic securitisation of Chinese FDI regarding the EU Single Market is present in the Commission’s discourse.

Arguments for protecting the EU Single Market are not protectionist in a liberal economic context because these defend liberal economic rules. To test the theoretical proposition of Buzan et al. (1998, pp. 100-103), one must focus on other economic referent objects. Here, the Commission links the call to protect the economic competitiveness of EU business, or “the EU’s technological edge” (EC, 2017d, p. 5; EC, 2017e, p. 6), to the military referent objects. The Commission argues that predatory foreign acquisitions in Europe’s high-tech sector are not only detrimental to the EU’s technological edge but also to its strategic capabilities, especially critical technologies (EC, 2017d, p. 5; EC, 2019, p. 67). Moreover, the Commission underlines that unfair investment practices endanger the survival of European companies that, in turn, will cause financial instability that harms the public order within the Union (ECHR, 2019, p. 4; EC, 2020b, p. 5). This threat description matches the way the Commission portrays China in the Commission Communications on the EU’s strategy on China. The securitising actor warns against China’s strategic and unfair investment practices in cutting-edge sectors, most notably the EU’s high-tech sector (ECHR, 2019, pp. 8-10), to create “national champions able to compete globally” (ECHR, 2016, p. 6). Meanwhile, it presents the Regulation (EU) 2019/452 as a tool to stop China’s unfair state-subsidised investments in Europe (ECHR, 2019, p. 11). Therefore, the Commission establishes the economic securitisation of Chinese FDI regarding the EU’s technological edge based on military security arguments. This form of military-economic securitisation confirms the theoretical proposition.

Another discursive link was found between the economic referent object ‘European workers’ and the political referent object ‘EU integration project’. Against the background of the ‘China threat’ discourse, the Commission presents the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation as a tool to protect EU projects that are a source of jobs, which serves the EU’s wider purpose of protecting European workers (EC, 2017b, p. 3, p. 18). This form of political-economic securitisation was relatively weak as only two instances of it were found, but it still confirms the theoretical proposition by Buzan et al. that the economic security sector is not a stand-alone analytical lens in a liberal economic context (1998, pp. 100-103). In sum, the discursive links between the economic, military, and political referent objects create a sense of cross-securitisation that adds another layer to the Commission’s existential threat discourse. This enhances the legitimacy of the introduction of the extraordinary measure.

Military Securitisation

The Commission’s military ‘China threat’ discourse builds further on the binary distinction between the EU’s traditional and emerging investment partners, as explained in the above-mentioned section. However, it juxtaposes the market-oriented interests of the EU with the strategic interests of the emerging powers. An important finding in all documents and speeches is that foreign State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) are presented as the antagonist – the actor working against the strategic interests of the EU – in the storyline about the changing foreign investment patterns. In the context of proposing the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation, reading between the lines reveals that China plays the role of the antagonist:

In the past two years, as Mr. Lange said, there has been a rise in the purchasing of strategic assets in the European Union by non-EU investors. A significant number of those are state-owned enterprises. Some are subsidised or backed by foreign governments. And often, these countries have major investment barriers in place (Malmström, 2018, January 23, 14:36:01).

State-owned Enterprises undertake a significant share of outward foreign direct investment, in some cases as part of a declared government strategy. […] In this context, there is a risk that in individual cases foreign investors may seek to acquire control of or influence in European undertakings whose activities have repercussions on critical technologies, infrastructure, inputs, or sensitive information (EC, 2017d, p. 5).

These passages implicitly refer to Chinese FDI, given the socio-historical context. The lack of market reciprocity in the Sino-EU investment relations and the Chinese FDI peak in Europe in 2016, two years earlier, sparked the political debate about the EU-wide FDI screening (Simon, 2020, pp. 44-45). Another reference to China is the mentioning of strategic FDI in Europe by SOEs as part of a declared government strategy. The infamous Belt and Road Initiative and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank are infrastructure development strategies declared by the Chinese government in 2013 and 2015 respectively, in which FDI and SOEs are important elements (Meunier & Nicolaidis, 2019, p. 107). Therefore, the securitising actor implicitly portrays China as threatening Europe’s strategic capabilities.

These implicit ‘China threat’ expressions became more explicit as the legislative process of Regulation (EU) 2019/452 progressed. To compensate for the non-publication of an impact assessment, the Commission published an SWD in 2019 on the development of FDI flows in Europe (Grieger, 2019, p. 6). In this document, Chinese FDI is linguistically singled out as the primary example of the rise in foreign SOEs that strategically invest in Europe’s high-tech sector, e.g., “with China standing out in terms of acquisitions” (EC, 2019, p. 1). Its publication date is the day after the submission of the Joint Communication by the Commission and the High Representative on 12 March 2019, which warns against the strategic investments of Chinese SOEs and calls for the swift implementation of the Regulation (EU) 2019/452 (ECHR, 2019, pp. 8-10). Later, in a public hearing on 30 September 2019, Trade Commissioner-designate Phill Hogan refers to this Joint Communication after stating that “we share a common understanding of the security challenges imposed by China’s subsidies and the heavy involvement of the state in its economy” (Hogan, 2019, September 30, 18:50:48). The claim to share a common understanding is an evidentiality that presents the idea of a ‘China threat’ as common sense without providing evidence. Whether this threat is real or not, this quote reveals the normativity hidden in the Commission’s ‘China threat’ discourse. These intertextual references and the explicit ‘China threat’ discourse constitute the reality effect of perceiving Chinese FDI as the paragon of state-controlled foreign investments that existentially threaten Europe’s strategic capabilities.

There are two linguistic strategies that the Commission uses to present the military referent objects as existentially threatened, which deserve attention. Firstly, it uses the metaphor “naïve free traders”, which was coined by Commission President Jean-Claude Junker to stress that Europeans do not sufficiently consider the true strategic motives of the antagonist (Rogelja & Tsimonis, 2020, p. 110). In his State of the Union Address, Junker emphasises that “we are not naïve free traders. Europe must always defend its strategic interests. This is why, today, we are proposing a new EU framework for investment screening” (2017, September 13). Not surprisingly, the DG Trade also uses this metaphor in a press statement (EC, 2018, November 20), and in a public hearing as Commissioner Malmström emphasises that “we shall not be naïve” (Malmström, 2018, January 23, 14:35:34). This figure of speech is a hypothetical scenario in which “the predatory buying of strategic assets by foreign investors” (EC, 2020, p. 5), most notably China, happens right under the eyes of the EU, if it does not screen FDI. Therefore, this metaphor induces the logic of survival that, in turn, achieves the military securitisation of Chinese FDI.

The second linguistic strategy is the specific use of the adjectives ‘critical’ and ‘essential’ to emphasise the existential threat. It was found in the official policy proposal (EC, 2017b), the press statements (EC, 2017, September 14; EC, 2018, November 20), the reports (EC, 2017b, p. 5; EC, 2017c, pp. 5-6), and the public hearings. In the public hearing on 30 September 2019, for example, the Trade Commissioner-designate Hogan argues:

We also need to strengthen the security of our critical infrastructure and our technological base, as outlined in the March 2019 Communication on China […], beefing up this particular screening mechanism is essential if we want to protect our critical technologies and our critical infrastructure (Hogan, 2019, September 30, 18:52:08).

While the quote reiterates the normative association between Chinese FDI and security threatening FDI, the emphasised passages present the critical technologies and infrastructure as lost if the FDI screening mechanism is not implemented. The rhetorical hypothesis – we need to strengthen the security, which is essential if we want to protect the strategic capabilities – urges the audience to act in a way that would ensure such protection, in this case, the implementation of the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation. This existential threat scenario induces the logic of survival that is integral to successful securitisation (Waever, 2009, p. 22). The same linguistic strategy is used to present the public order in the Union as existentially threatened because it is bound to the EU’s strategic capabilities. The mentioning of the latter consistently precedes the former, e.g., “the purchase of European companies that develop technologies or maintain infrastructures that are essential to perform critical functions in society and the economy” (EC, 2017b, p. 10). Public order is the ability to perform critical functions in society. While military securitisation based on the public order does not occur independently, it adds another layer to the Commission’s threat discourse.

The findings suggest that Europe’s strategic capabilities play the starring role in the Commission’s security rhetoric, as it is the most frequently mentioned of all referent objects across all documents. Given that the political-legal constitution of the EU is anti-protectionist and anti-discriminatory, the military security arguments are most appropriate in legitimising the extraordinary measure in a legislative context (Bickenbach & Liu, 2018, p. 19). This helps to explain why the strategic capabilities in the EU are not only important in the military securitisation of Chinese but also in the economic and political security rhetoric, which is elaborated on in sections before and after.

Political Securitisation

The Commission’s political ‘China threat’ discourse is similar to the military variant as it centres around the idea of increasing Chinese direct investments that acquire Europe’s strategic capabilities, which, in turn, are detrimental to the EU integration project. Consequently, the political securitisation of Chinese FDI is intertwined with the military security argument to protect the EU’s strategic assets. As Figure 1 shows, political securitisation is important if not dominant in the speeches, as President Junker’s State of the Union is illustrative of the political threat discourse:

Today we are proposing a new EU framework for investment screening […] If a foreign, state-owned, company wants to purchase a European harbour, part of our energy infrastructure or a defence technology firm, this should only happen in transparency, with scrutiny and debate. It is a political responsibility to know what is going on in our own backyard so that we can protect our collective security if needed (Junker, 2017, September 13).

The quote’s threat discourse becomes political by the emphasis on the EU as the protagonist in the storyline. Not surprisingly, the analysis found that all instances of the political securitisation of Chinese FDI are based on the EU integration project, not the sovereignty of Member States. Here, President Junker emphasises that it is a political responsibility to protect these strategic assets, with a specific use of the pronouns ‘we’ and ‘our’. To state ‘our own’ is redundant because ‘our’ already indicates a form of possession. This linguistic construction fosters a relationship between the speaker and the audience that, in turn, enhances the sentiment of being a Union of Europeans that is to be protected. The mentioning of “our own backyard” refers to Greece given its geographical location that is not in the heart of Europe but at the southern border of the Union, that is, the backyard of the EU. With a military undertone, the emphasised passages about a foreign SOE purchasing a European harbour implicitly refer to the notorious purchases of large stakes in the Greek Piraeus Port by the Chinese shipping group COSCO in 2008 and 2016. As COSCO is a former SOE with ties to the Chinese government, this investment deal has been perceived as an example of China’s ‘divide and conquer’ investment strategy in Europe that disintegrates the EU (Meunier, 2014c; Rogelja & Tsimonis, 2020, p. 116). In the past decade, Greece adopted a more lenient diplomacy approach towards China than other Member States because of its economic dependence on Chinese FDI, which is seen as detrimental to the EU’s internal unity (Meunier, 2019, p. 21; Chan & Meunier, 2020, p. 22). Similarly, Commissioner Malmström implicitly refers to the Sino-Greek investment relations as she states in the public hearing on 23 January 2018:

There is a Chinese proverb saying that the best time to plant a tree was twenty years ago, but the second-best time is now. So, public order and security is not about being right one day. It is about being right all the time from day one […] The future of our Union depends on how we prepare for the future […] We need to secure the foundations of the European Union […] As I started with a Chinese proverb, I will end with a Greek one, saying that: “a society grows great when old men plant trees whose shade they know they shall never sit in”. In this case, things are more urgent than it might suggest in the proverb” (Malmström, 2018, January 23, 14:34:20).

The words ‘urgent’, ‘the best time is now’ and ‘need to secure’ create a sense of urgency that fosters the idea of being existentially threatened. The emphasised passages express that the future and the foundation of the EU will lose their quality of existence if the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation is not implemented, which meets the exact criteria of a successful instance of securitisation (Buzan et al., 1998, p. 26). The Chinese and Greek proverbs do not only foster a sense of urgency, but the very mentioning of them also implicitly refers to the rapidly increasing Sino-Greek investment relations that were an issue of concern in the wider public debate about Chinese FDI in Europe (Rogelja & Tsimonis, p. 120). The reality effect of these discursive elements is the idea that Chinese FDI existentially threatens the EU integration project, with a particular focus on China’s alleged strategy to woo Greece to its side with FDI.

Meanwhile, the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation is consistently presented as a mechanism “to cooperate and exchange information on investments from third countries” (EC, 2018, November 20; EC, 2019, February 12). This describes the policy instrument as a tool to counter the disintegrating impact of hostile FDI in Europe. Moreover, the Commission presents the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation as a tool to protect “projects and programmes which serve the Union as whole” (EC, 2017a, p. 18), “our Union” (Junker, 2017, September 13), “project or programmes of Union interests” (EC, 2017b, p. 20), and “projects of the Union’s interest, like Galileo or Horizon 2020, fundamental for our future” (Malmström, 2019, February 13; 18:51:32). It becomes clear that the Commission’s discourse establishes the political securitisation of Chinese FDI regarding the EU integration project, which legitimises the introduction of the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation.

Societal Securitisation

The societal security sector focuses on arguments about collective identities (Buzan et al., 1998, p. 7). Here, the Commission juxtaposes the EU as the promoter of liberal democracy (Junker, 2017, September 13), with China as an authoritarian “one-party system with a state-dominated model of capitalism” (ECHR, 2016, p. 17). However, there was only one instance of societal securitisation in the March 2019 Communication on the EU’s China Strategy. The Commission states that the European social model will be lost if the EU does not adapt to the changing investment environment and strengthen its domestic policies with the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation (ECHR, 2019, pp. 2-6, p. 17). Hence, the societal securitisation of Chinese FDI is relatively weak. An explanation is that openly securitising Chinese investors based on collective identities would contradict the Commission’s claim that the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation is non-discriminatory (EC, 2017b, p. 3). Nevertheless, Figure 1 shows that the other forms of securitisation outweigh the almost absent societal security rhetoric and legitimise the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation.

Conclusion

The introduction of the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation is not only extraordinary but also harmful to its legitimacy, as the open market mantra is built into its liberal identity. This thesis aimed to answer why the EU introduced this extraordinary measure. Presenting an issue as an existential threat – securitisation – can legitimise an extraordinary measure (Buzan et al., 1998, p. 26), hence, discourse analysis was conducted on the Commission’s documents and speeches about the Regulation (EU) 2019/452 from 2016 to 2020. Using the securitisation theory of the Copenhagen School, this thesis uncovered the securitisation of Chinese FDI in the Commission’s policy discourse on the proposal for establishing a framework for the screening of FDI into the Union. It reveals that the idea of a ‘China threat’ is based on a binary distinction between the EU as the market-oriented protagonist and China as the strategic antagonist. Against this background, economic, military, and political securitisation were prevalent in the Commission’s discourse, with each showing dominance in a discourse format that is appropriate for their designated style of speaking security. This may suggest that the Commission considers when to speak which type of security rhetoric. Only societal securitisation proved to be irrelevant, but it is outweighed by the other forms of securitisation.

The findings show that the political securitisation of Chinese FDI presents the EU integration project as existentially threatened by the strategic asset-seeking investments from China. It is based on the same threat discourse as the military variant. The military securitisation of Chinese direct investments centres around the idea of China’s predatory buying of Europe’s strategic capabilities via its SOEs, which, in turn, is detrimental to the public order in the EU. Meanwhile, the economic securitisation of Chinese FDI is based on the idea of Chinese investors who do not comply with the EU’s economic rulebook, which existentially threatens the EU Single Market, the EU’s economic competitiveness and European workers. To avoid protectionist arguments that would be illegitimate in the liberal economic context of the EU, the Commission discursively linked the call to protect the economic competitiveness, and European workers to arguments for protecting the strategic capabilities, the public order, and the EU integration project. The theoretical implication of this particular finding is that this thesis confirms the suggestion by Buzan et al. that securitisation analysts must include other security sectors to comprehensively understand instances of economic securitisation in a liberal economic context (1998, pp. 100-103). In summary, it can be argued that the Commission implicitly and explicitly expressed the idea that Chinese FDI in Europe existentially threatens the EU’s security, which, in turn, legitimised the introduction of the extraordinary measure of the Regulation (EU) 2019/452.

The risk of using discourse analysis as the research method is that the analysis is interpretative and may become normative (Hardy et al., 2004, p. 21). However, the use of a codebook and the software programme ATLAS.ti that allows for sharing the analytical notes aimed to establish an empirically valid and reliable study. Furthermore, using the securitisation theory of the Copenhagen School did not allow for analysing the response of the MEPs to the Commission’s securitising speech act in the EP debate and the public hearings. For those interested in studying the response of the audience, a suggestion for future research is to use the sociological securitisation theory developed by Balzacq (2011) and Salter (2011). Suitable research methods are process tracing, ethnographic research, and content analysis to understand the socio-cultural context that enabled the MEPs’ acceptance of the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation (Balzacq et al., 2016, p. 519).

Nevertheless, this research project accomplished to reveal the Commission’s implicit and explicit ‘China threat’ discourse on FDI screening. Given the authority of the securitising actor, the wider societal implication is that the Commission feeds into the construction of a shared understanding that Chinese investments are not an economic opportunity but a security threat. The feeling of urgency to screen FDI has been carried on by the so-called geopolitical Commission under President Ursula von der Leyen. On 17 June 2020, it proposed a general market scrutiny instrument that addresses the market-distorting effects of foreign subsidised investments, most notably from China, through investment screening (EC, 2020c, pp. 4-5). While this Commission proposal calls for the protection of fair competition, the joint letter of Germany, France, and Italy requesting EU-wide FDI screening that preceded the Regulation (EU) 2019/452 was rejected by smaller Member States for the exact same argumentation (Simon, 2020, pp. 45-48). Since this thesis does not offer an explanation on this issue, it may be that framing Chinese FDI as an existential threat is important in the Commission’s agenda-setting practices. Research on the policy entrepreneurship of the Commission regarding the framing of the Chinese FDI may provide further insights into this matter.

References

Aggarwal, V. K., & Reddie, A. W. (2020). New economic statecraft: Industrial policy in an era of strategic competition. Issues & Studies: A Social Science Quarterly on China, Taiwan and East-Asian Affairs, 56(2), 1-29. https://doiorg.ezproxy.ub.unimaas.nl/10.1142/S1013251120400068

Balzacq, T. (2005). The three faces of securitization: Political agency, audience, and context. European Journal of International Relations, 11(2), 171-201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066105052960

Balzacq, T. (2011). A theory of securitization: Origins, core assumptions and variants. In T. Balzacq (Ed.), Securitization Theory: How security problems emerge and dissolve (pp. 1-30). Routledge.

Balzacq, T., Léonard, S., & Ruzicka, J. (2016). ‘Securitization’ revisited: Theory and cases. International Relations, 30(4), 494–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117815596590

Bickenbach, F., & Liu, W. H. (2018). Chinese direct investment in Europe – Challenges for EU FDI policy. CESifo Forum, Ifo Institut–Leibniz-Institute for Economic Research at the University of Münich, 19(4), 15-22. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/199017/1/CESifo-Forum-2018-4-p15-22.pdf

Bigo, D., & Tsoukala, A. (2008). Terror, Insecurity and Liberty: Illiberal Practices of Liberal Regimes after 9/11. Routledge.

Borowicz, A. (2020). The shift of the policy towards FDI in European Union: Determinants and challenges. European Integration Studies, 14(1), 117-124. http://dx.doi.org/10.5755/j01.eis.1.14.27556

Buzan, B., Wæver, O., & De Wilde, J. (1998). Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Lynne Rienner Pub.

Casarini, N. (2015). Is Europe to benefit from China’s Belt and Road Initiative? Istituto Affari Internazionali & JSTOR, 15(40), 1-11. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep09729

Chan, Z., & Meunier, S. (2020). Behind the screen: Understanding national support for a Foreign Investment Screening Mechanism in the European Union. Social Science Research Network. Advance online publication. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3726973

Christiansen, T., & Maher, R. (2017). The rise of China: Challenges and opportunities for the European Union. Asia Europe Journal, 15(2), 121–131. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10308-017-0469-2

Defraigne, J. C. (2017). Chinese outward direct investments in Europe and the control of the global value chain. Asia Europe Journal: Studies on Common Policy Challenges, 15(2), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-017-0476-3

Esplugues, M. C. (2018). More targeted approach to Foreign Direct Investment: The establishment of screening systems on national security grounds. Brazilian Journal of International Law, 15(2), 440-468. https://doi.org/10.5102/rdi.v15i2.5365

European Commission (EC). (2017a). Reflection Paper on Harnessing Globalisation (COM(2017)240).

European Commission (EC). (2017b). Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and the Council. Establishing a Framework for Screening Foreign Direct Investments into the European Union (COM(2017)487).

European Commission (EC). (2017c). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A Balanced and Progressive Trade Policy to Harness Globalisation (COM(2017)492).

European Commission (EC). (2017d). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Welcoming Foreign Direct Investment while Protecting Essential Interests (COM(2017)494).

European Commission (EC). (2017e). Commission Staff Working Document. Accompanying the document (COM(2017(487) (SWD(2017)297).

European Commission (EC). (2017, September 14). State of the Union 2017 – Trade Package: European Commission Proposes Framework for Screening Foreign Direct Investment. The Official Website of the European Commission, News Archive. http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/press/index.cfm?id=1716

European Commission (EC). (2018, November 20). Commission Welcomes Agreement on Foreign Investment Screening Framework. The Official Website of the European Commission, Press Corner. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_18_6467

European Commission (EC). (2019). Commission Staff Working Document on Foreign Direct Investment in the EU (SWD(2019)108).

European Commission (EC). (2020a). Commission Staff Working Document on the Movement of Capital and the Freedom of Payments (SWD(2020)39).

European Commission (EC). (2020b). Communication from the Commission. Guidance to the Member States Concerning Foreign Direct Investment and Free Movement of Capital from Third Countries, and the Protection of European Strategic Assets, ahead of the Application of Regulation (EU) 2019/452 (FDI Screening Regulation) (COM(2020)1981).

European Commission (EC). (2020c). White Paper on Levelling the Playing Field as Regards Foreign Subsidies (COM(2020)253).

European Commission (EC). (2021). EU Investment Policy. https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/accessing-markets/investment/

European Commission and the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (ECHR). (2016). Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the European Council and the Council. Elements for a New Strategy on China (JOIN(2016)30). European Commission.

European Commission and the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (ECHR). (2019). Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the European Council and the Council. EU-China: A Strategic Outlook (JOIN(2019)5). European Commission.

Eurostat. (2019, July 1). Foreign Direct Investment – Stocks. Eurostat Statistics Explained. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Foreign_direct_investment_-_stocks

Floyd, R. (2016). Extraordinary or ordinary emergency measures: What and who defines the ‘success’ of securitization? Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 29(2), 677-694. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2015.1077651

Floyd, R. (2019). Evidence of securitisation in the economic sector of security in Europe? Russia’s economic blackmail of Ukraine and the EU’s conditional bailout of Cyprus. European Security, 28(2), 173-192. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2019.1604509

Grieger, G. (2019). Briefing EU Legislative Process – EU Framework for FDI Screening. European Parliament Research Service. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPRS_BRI(2018)614667

Hardy, C., Harley, B., & Phillips, N. (2004). Discourse analysis and content analysis. Two solitudes? Qualitative Methods, 2(1), 19-22. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.998649

Heim, I., & Ribberink, N. (2021). Between growth and national security in host countries: FDI regulation and Chinese outward investments in Australia’s critical infrastructure. AIB Insights, 21(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.46697/001c.19506

Hogan, P. (2019, September 30). European Commission Representative Answers Questions put by Members of the European Parliament from the Committee on International Trade [Speech video recording]. European Parliament Multimedia Centre. https://multimedia.europarl.europa.eu/en/hearing-of-phil-hogan-commissioner-designate-trade_20190930-1830-SPECIAL-HEARING-2Q2_vd

Hooijmaaijers, B. (2019). Blackening skies for Chinese investment in the EU? Journal of Chinese Political Science, 24(3), 451-470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-019-09611-4

Ishikawa, T. (2020). Investment screening on national security grounds and international law: The case of Japan. Journal of International and Comparative Law, 7(1), 71-98. https://www.jicl.org.uk/journal/june-2020/investment-screening-on-national-security-grounds-and-international-law-the-case-of-japan

Jerdén, B. (2014). The assertive China narrative: Why it is wrong and how so many still bought into it. The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 7(1), 47-88. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/pot019

Junker, J. (2017, September 13). Transcript of the State of the Union Address 2017. The Official Website of the European Commission, Press Release. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_17_3165

Lai, K. (2021). National security and FDI policy ambiguity: A commentary. Journal of International Business Policy, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-020-00087-1

Liu, I. T. (2020, July 7). The economics of national security in Hong Kong. The Lowy Institute. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/economics-national-security-hong-kong

Malmström, C. (2018, January 23). European Commission Representative Answers Questions put by Members of the European Parliament from the Committee on International Trade [Speech video recording]. European Parliament Multimedia Centre. https://multimedia.europarl.europa.eu/en/committee-on-international-trade_20180123-1430-COMMITTEE-INTA_vd

Malmström, C. (2019, February 13). European Commission Speech in the European Parliament Debate about the Proposal for the EU Regulation to Screen Foreign Direct Investments into the Union [Speech video recording]. European Parliament Multimedia Centre. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/plenary/en/vod.html?mode=chapter&vodLanguage=EN&playerStartTime=20190213-18:41:58&playerEndTime=20190213-19:38:52#

Manners, I. (2002). Normative power Europe: A contradiction in terms? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 40(2), 235-258. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00353

Meunier, S. (2014a). A Faustian bargain or just a good bargain? Chinese Foreign Direct Investment and politics in Europe. Asia Europe Journal, 12(1), 143-158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-014-0382-x

Meunier, S. (2014b). ‘Beggars can’t be choosers’: The European crisis and Chinese Direct Investment in the European Union. Journal of European Integration, 36(3), 283-302. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2014.885754

Meunier, S. (2014c). Divide and conquer? China and the cacophony of foreign investment rules in the EU. Journal of European Public Policy, 21(7), 996-1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.912145

Meunier, S. (2019). Chinese Direct Investment in Europe: Economic opportunities and political challenges. In K. Zeng (Ed.), Handbook on the International Political Economy of China (pp. 98-112). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Meunier, S., Burgoon, B. & Jacoby, W. (2014). The politics of hosting Chinese investment in Europe – An introduction. Asia Europe Journal, 12, 109–126. https://doi-org.ezproxy.ub.unimaas.nl/10.1007/s10308-014-0381-y

Meunier, S., & Nicolaidis, K. (2019). The geopoliticization of European trade and investment policy. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(1), 103-113. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12932

Meunier, S., & Mickus, J. (2020). Sizing up the competition: Explaining reform of European Union competition policy in the Covid-19 era. Journal of European Integration, 42(8), 1077-1094. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1852232

Moskvan, D. (2017). The European Union’s competence on foreign investment: New and improved. San Diego International Law Journal, 18(2), 241-262. https://digital.sandiego.edu/ilj/vol18/iss2/3

Nicolas, F. (2014). China’s direct investment in the European Union: Challenges and policy responses. China Economic Journal, 7(1), 103-125. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538963.2013.874070

Pan, C. (2004). The “China threat” in American self-imagination: The discursive construction of other as power politics. Alternatives, 29(3), 305-331. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40645119

Paszak, P. (2017). Chinese investment policy in Europe between 2011 and 2017: Challenges and threats to the security of European Union countries. Polish Journal of Political Science, 3(4), 7-29. http://yadda.icm.edu.pl/yadda/element/bwmeta1.element.desklight-55cb1148-f65e-4101-af7e-529bef31fcd5

Peters, M. A., Means, A. J., Ericson, D. P., Tukdeo, S., Bradley, J. P., Jackson, L., & Misiaszek, G. W. (2021). The China-threat: Discourse, trade, and the future of Asia. A Symposium. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 53, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2021.1897573

Riela, S., & Zámborský, P. (2020). Screening of foreign acquisitions and trade in critical goods. Asia-Pacific Journal of EU Studies, 18(3), 55-83. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3774015

Roberts, A., Moraes, H. C., & Ferguson, V. (2019). Toward a geo-economic order in international trade and investment. Journal of International Economic Law, 22(4), 655-676. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgz036

Rogelja, I., & Tsimonis, K. (2020). Narrating the China threat: Securitising Chinese economic presence in Europe. The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 13(1), 103-133. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/poz019

Rosecrance, R., & Thompson, P. (2003). Trade, foreign investment, and security. Annual Review of Political Science, 6(1), 377-398. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.6.121901.085631

Salter, M. B. (2011). When securitisation fails: The hard case of counter-terrorism programs. In T. Balzacq (Ed.), Securitisation Theory: How Security Problems Emerge and Dissolve (pp. 116-132). Routledge.

Santander, S., & Vlassis, A. (2021). The EU in search of autonomy in the era of Chinese expansionism and COVID‐19 pandemic. Global Policy, 12(1), 149-156. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12899

Schill, S. W. (2019). The European Union’s Foreign Direct Investment screening paradox: Tightening inward investment control to further external investment liberalization. Legal Issues of Economic Integration, 46(2), 105-128. https://www.kluwerlawonline.com/abstract.php?area=Journals&id=LEIE2019007

Scholvin, S., & Wigell, M. (2019). Geo-economic power politics: An introduction. In M. Wigell, S. Scholvin & M. Aaltola (Eds.), Geo-Economics and Power Politics in the 21st Century: A revival of economic statecraft (pp. 1-13). Routledge Global Security Studies.

Simon S. (2020). Investment screening: The return of protectionism? A political account. In S. Hindelang & A. Moberg (Eds.), YSEC Yearbook of Socio-Economic Constitutions 2020. YSEC Yearbook of Socio-Economic Constitutions (pp. 43-52). Springer.

Song, W. (2015). Securitization of the “China threat” discourse: A poststructuralist account. China Review, 15(1), 145–169. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24291932

Stoffers, M. (2021). Beyond credibility: Advanced document analysis. In M. Stoffers (Ed.), Research Methods: Advanced Document Analysis (pp. 11-20). Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Maastricht University.

Svoboda, O. (2020). The end of European naivety: Difficult times ahead for SCEs/SOEs investing in the European Union? Transnational Dispute Management Journal, 17(6), 1-13. https://www.transnational-dispute-management.com/article.asp?key=2776

Wæver, O. (2009). What exactly makes a continuous existential threat existential? In O. Barak & G. Sheffer (Eds.), Existential Threats and Civil-Security Relations (pp. 19-36). Lexington Book.

Watson, S. D. (2012). ‘Framing’ the Copenhagen School: Integrating the literature on threat construction. Millennium – Journal of International Studies, 40(2), 279–301. https://doi-org.ezproxy.ub.unimaas.nl/10.1177/0305829811425889

Wendt, A. (1992). Anarchy is what states make of it: The social construction of power politics. International organization, 46(2), 391-425. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300027764

Appendix

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- EU Foreign Policy in East Asia: EU-Japan Relations and the Rise of China

- Risk Theory vs. Securitisation: An Analysis of the Global Surveillance Program

- Humanitarianism and Securitisation: Contradictions in State Responses to Migration

- High North – Low Tension? Norway, Russia and Securitisation in the Arctic

- Legal ‘Black Holes’ in Outer Space: The Regulation of Private Space Companies

- China in Africa: A Form of Neo-Colonialism?