The PLA was formed in 1927 after the Nanchang uprising, and it has played an important role in China’s domestic and foreign affairs. From 1952 to 2016, the PLA has undergone 11 major military modernisation and restructuring programmes and has grown significantly in military strength and capabilities. (Allen et al., 2016). Military modernisation is defined as upgrading and adopting new technologies or platforms to counter emerging challenges. Military restructuring refers to policies to improve the efficiency of the military and realigning its objectives to address current threats.

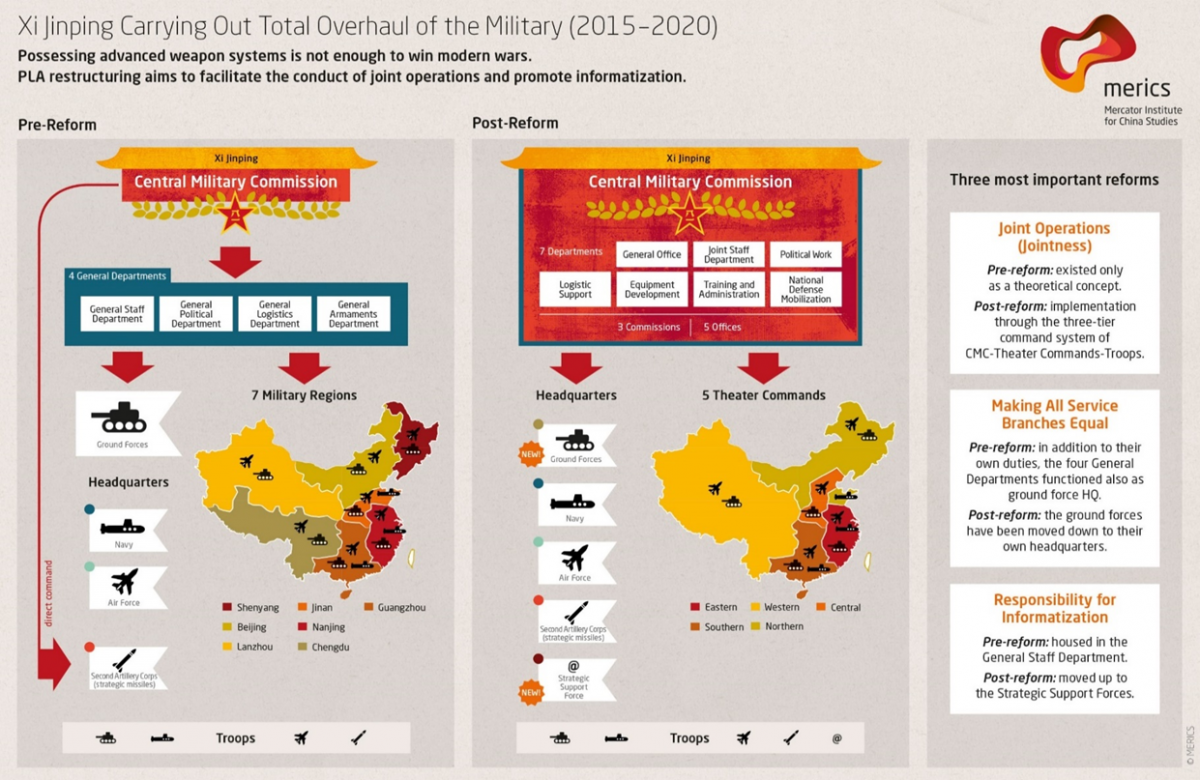

Under Mao, the PLA was instrumental in the formation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 and defending China’s borders. However, during the Cultural Revolution, the PLA became embroiled in civilian politics leading to domestic upheavals. After Mao’s death in 1976, Deng Xiaoping sought to reassert civilian control over the PLA by creating the Central Military Commission (CMC) in 1983 (Bullard and O’Dowd, 1986). The CMC represents the highest decision-making body within the PLA, and its chairmanship has been held by civilian leaders such as Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, and Xi Jinping. During Jiang and Hu’s Chairmanship, they emphasised military R&D to develop new weapons and streamline the PLA’s Command, Control and Computers (C3) systems after witnessing the US military’s technological dominance during the 1991 Gulf War (Kamphusen et al., 2014). Currently, Xi’s military reforms have overhauled the CMC’s structure and the Military Region (MR) system (See Annex A). Xi has also shifted the PLA’s focus from the army to the navy, especially given increasing maritime threats to China’s sovereignty. Furthermore, China’s rapid military modernisation has allowed China to reduce the military technology gap with the US.

Realist theories of the balance of power and power maximisation have often been invoked to explain China’s military modernisation and restructuring. However, the realist perspective is insufficient in accounting for why China’s military transformation only became visible in the past decade. I argue that China’s military modernisation and restructuring are driven by Xi Jinping’s personality, leadership and vision in transforming the PLA into a “World-Class” military by 2050. I will use the Interpretative Actor Perspective to analyse how Xi’s thoughts and actions drive China’s military modernisation and restructuring. Other factors such as the 1991 Gulf War, intensified threats to China’s “Core Interests” and China’s growing economic interests worldwide, will also be examined. This essay is organised into three sections. Section 1 briefly introduces the theoretical frameworks used, while section 2 outlines Xi’s personality and its implications on China’s foreign policy. Lastly, section 3 explores the reasons for China’s military modernisation and restructuring.

Interpretative Actor Perspective and Realism in Military Modernisation and Restructuring

The Interpretative Actor Perspective is similar to Social Constructivism as both underscore the salience of an intersubjective understanding of reality and logics of appropriateness (Carlnaes, 1992). However, Social Constructivism stresses on norms and social rules in interpreting individuals’ actions. Conversely, the Interpretative Actor Perspective analyses the reasons behind an actor’s thoughts and actions in decision-making (Hollis and Smith, 1990). Leaders can reconstitute social facts through practice and influence ideational structures, such as norms and rules. Therefore, leadership and vision are crucial in driving military modernisation and restructuring. For instance, Hitler’s indignation at Germany’s humiliation during the 1919 Treaty of Versailles kickstarted Germany’s military modernisation in 1935.

In contrast, realists opine that military modernisation and restructuring are due to an international struggle for power. Mearsheimer (2001) postulates that states are rational power maximisers seeking to ensure their survival in an anarchic international system, driving them to expand their military forces. The competition for power also compels states to engage in internal and external balance of power to prevent a hegemon from undermining state sovereignty (Waltz, 1979). Internally, the state builds up its military forces through modernisation, increased defence budgets, and restructuring. Externally, states would ally themselves with militarily powerful states to balance against a hegemon. However, increases in military power may lead to a security dilemma. An example would be the nuclear arms race between the US and USSR during the Cold War.

Xi Jinping’s Personality and Implications on China’s Foreign Policy Decision Making

This brief analysis of Xi’s personality provides an insight into his motivations for modernising and restructuring the PLA. According to Liao (2016) and Shan (2016), Xi Jinping is an ambitious leader with a strong sense of responsibility in promoting China’s development, and is assertive in pursuing his agendas. When Xi became President in 2013, he launched many bold foreign policy initiatives to accentuate China’s international standing. For instance, during a 2013 lecture in Kazakhstan’s Nazarbayev University, Xi announced the creation of the “New Silk Road” [now Belt and Road Initiative, BRI] to promote connectivity, trade and development across Central Asia. Since then, 138 countries have signed up for the BRI and it encompasses nearly 60% of the world’s population (Brookings Institute, 2020).

Besides Xi’s ambitions, he possesses a strong sense of responsibility in realising the “Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation.” Xi’s experiences of working with peasants in Yanan during the Cultural Revolution solidified his ideals that the party must lead China’s development (Foreign Policy, 2019). In October 2021, Xi vowed to complete the “historical task” of reunifying Taiwan by 2049 to remove the last vestiges of the Century of Humiliation.

Lastly, Xi is assertive in implementing his foreign policy initiatives. Xi idolises Mao Zedong for his strong leadership (Foreign Policy, 2019), a vital trait needed to sustain the CCP’s legitimacy and China’s survival. Liao (2016) posits that under Jiang and Hu, China’s foreign and defence policies were decentralised, affecting coherent policy making. Xi has since personalised and directed foreign and defence policies through the Central Leading Groups (CLGs) and his chairmanship of the CMC (Char and Bitzinger, 2017).

Driving Forces for China’s Military Modernisation and Restructuring

Xi Jinping’s Vision and Political Will

Xi Jinping’s vision of transforming the PLA into a “World-Class” military by 2050 and his political will in executing military reforms are crucial in hastening China’s military modernisation and restructuring since 2015, thereby strengthening its military prowess. According to Fravel (2020), there is no consensus of what constitutes a “World-Class” military, but it can be interpreted as possessing a strong military. Xi’s vision is moulded by his personal emphasis on China’s history and sovereignty, as evident from his Centenary of the founding of the CCP speech in July 2021, where he noted that China was a “great nation” that suffered a “Century of Humiliation” after the Opium Wars (Nikkei, 2021). To avert a repeat of history, the PLA needs to be capable of defending China’s sovereignty and developmental interests. To that end, Xi has set out three milestones for China’s military modernisation and restructuring (Hart et al., 2021):

- 2020: to achieve mechanisation and informatisation for the PLA Ground Forces

- 2027: during the Centenary of the PLA’s founding, the PLA needs to (a) integrate Artificial Intelligence (AI) and emerging technologies into the PLA’s military platforms, (b) accelerating the PLA’s organisational restructuring, (c) improving efficiency through integrating economic and security strategies, and (d) promoting Military-Civilian Fusion to align China’s economic development with the improvement of its military.

- 2035: to complete the PLA’s military modernisation and restructuring.

Since Xi’s 2015 military reforms, the PLA Ground Forces has made progress in achieving the 2020 milestone by fielding upgraded combat systems and communication equipment to coordinate joint operations. China is also on track in achieving its 2027 and 2035 objectives of modernising the military, particularly its navy and air force. According to the US Department of Defence (DOD)(2020), China has surpassed the US to become the world’s largest navy in terms of warships. RAND Corporation (2017) estimates that close to 70% of China’s navy is modern, as it possesses an array of advanced ballistic missiles and onboard systems. Moreover, 50% of China’s fighters and fighter-bombers are fifth-generation aircraft, which is characterised by stealth capabilities and the ability to network with other military units (RAND, 2017).

Besides vision, political will is required to execute difficult military restructuring programmes. According to You (2018), the PLA is a politically conservative organisation that resists change as it affects the vested interests of high-ranking military commanders. Such inertia has enabled outdated military systems to persist, slowing the pace of military reforms in China. When Xi Jinping was unanimously elected as CMC Chairman in 2018, Xi restructured the CMC by reducing its membership from 11 to 7 while appointing 5 younger Generals to the helm to ensure the CMC’s loyalty to Xi (Li, 2018). For example, two CMC deputies – Xu Qiliang and Zhang Youxia – had served in Fujian and Zhejiang when Xi was the Provincial Chief. Xi also promoted new CMC members based on military experience and professionalism to improve the implementation of military reforms (Li, 2018). Moreover, in 2021, China revised its National Defence Law to allow the CMC to mobilise both military and civilian resources, such as technology and transportation, for national defence (Lowsen, 2021). Therefore, institutional restructuring of the PLA allowed Xi to consolidate power to enact comprehensive military reforms with minimal opposition.

Although it can be argued that Xi’s military restructuring and modernisation are influenced by political reasons, such as the consolidation of power, I opine that these reforms had enabled Xi to implement his decisions with little pushback from the CCP and the PLA. Currently, China’s increased military strength had attracted the attention of the international community. According to the US DOD report (2020), China’s military has already surpassed the US in conventional ballistic missiles, air-defence systems, and shipbuilding. Hence, I argue that Xi’s assertive leadership and his vision of a “World-Class” military by 2050 is the main driving force for China’s military transformation.

Learning from the 1991 Gulf War

The US’s overwhelming victory over Iraq during the 1991 Gulf War roused concerns that China’s military was obsolete, which initiated its military modernisation and restructuring programmes. Iraq’s military was similar to that of China in doctrines and equipment. Firstly, China and Iraq adhered to the doctrine of People’s War under Modern Conditions, which emphasised a combination of mechanised warfare, and guerrilla tactics (Jencks, 1992). Secondly, both countries possessed plenty but outdated tanks, aircraft, and artillery. Conversely, the US had sophisticated military technology such as stealth bombers and guided cruise missiles. Thirdly, Iraq and China lacked coordinated command and control systems between the army, navy and air force to conduct joint operations, while the US had integrated inter-services military networks (You, 1999). The US’s swift defeat of Iraq heightened China’s perception of its military inadequacies vis-à-vis the US, prompting the CMC to conclude that China’s military weaknesses was in its equipment than military structure, and advocated for the increase in defence expenditure, improvements in military R&D and acquiring sophisticated hardware (Jencks, 1992).

The military modernisation programmes proposed after the end of the Gulf War are being successfully implemented:

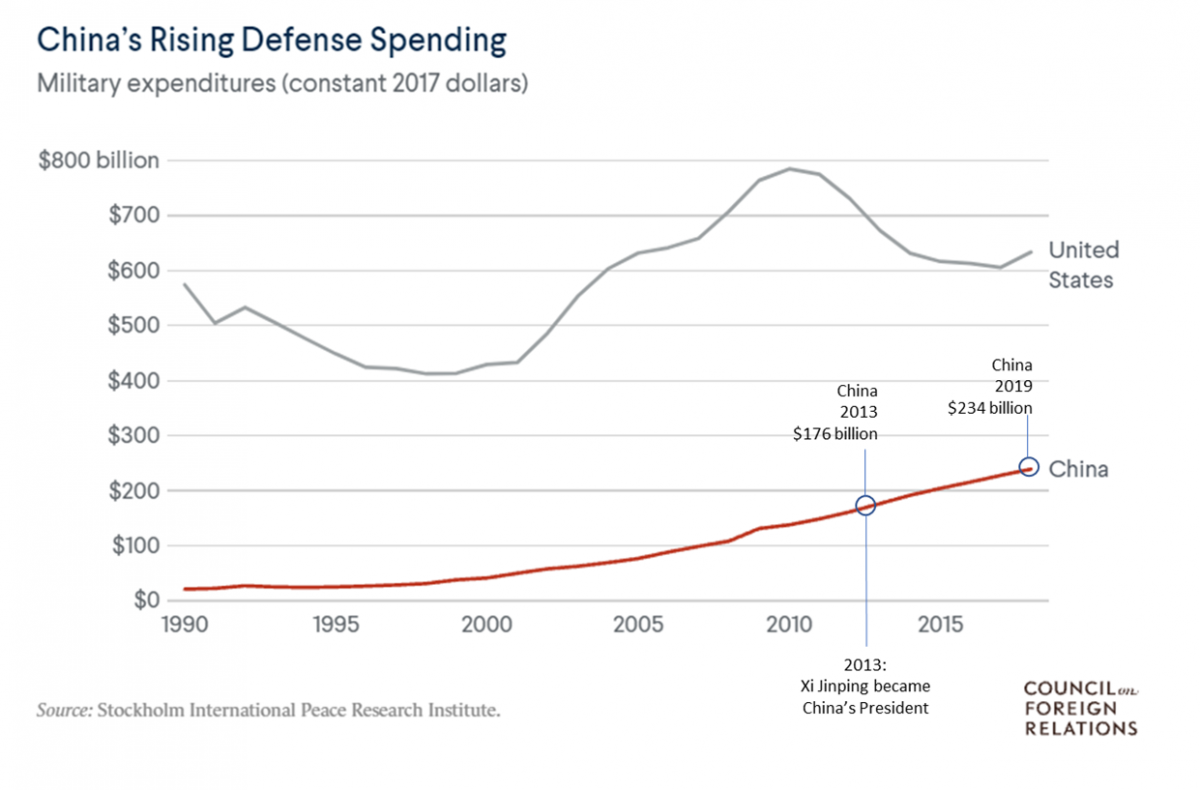

- Increased defence spending: China has increased its military expenditure from $21 billion in 1991 to $234 billion in 2019, a nearly 10-fold increase over three decades. Despite China’s military spending being 3 times less than the US, the latter’s defence expenditure only increased 23% in the same period (See Annex B).

- Increased R&D in military technology: China’s 14th Five-Year-Plan announced increases in R&D spending on emerging technologies to support the PLA’s modernisation. For example, China is researching into the military uses of AI and quantum computing. China’s increased emphasis on semiconductors is crucial in developing specialised chips for precision strike missiles and drones. This is aligned with Xi’s 2027 PLA modernisation milestone of promoting Military-Civilian fusion in defence technologies (IISS, 2021).

Additionally, the PLA has focused on joint inter-services military operations to improve coordination during conflicts. In August 2021, China and Russia participated in the Zapad military drills involving aircraft and drones. The 1991 Gulf War laid the foundations for China’s military transformation to narrow the military technology gap with the US.

Although the 1991 Gulf War started China’s military modernisation and restructuring, it does not explain why China’s military build-up only became prominent in recent years. Instead, I opine that Xi’s ambitions for a strong PLA accelerated the post-Gulf War military reforms. Firstly, China’s economy was still developing in the 1990s, and it lacked the resources to acquire sophisticated weapons and conduct R&D. By 2000, the PLA’s ground, air, and sea forces were “sizeable” but obsolete (US DOD, 2020). Under Xi Jinping, China’s defence spending increased by 25% from 2013 and 2019 (Annex B). Additionally, Xi increased military R&D spending by 10.7% in 2021 and would increase it further by 5% annually (IISS, 2021). Secondly, China started emphasising joint military operations after Xi’s Chairmanship of the CMC Joint Operations Command Center (JOCC) in 2016, which improved inter-services coordination to augment the PLA’s firepower in combat.

Growing Threats to China’s ‘Core Interests’

Realists would posit that growing military threats to China’s “Core Interests” of sovereignty and security in the South China Sea and Taiwan are key drivers for China’s military modernisation and restructuring. China’s 2019 Defence White Paper (Xinhua, 2019) lists the US’s military presence and Taiwanese separatism as threats to China’s security. Military alliances such as AUKUS and Quad have raised concerns about an anti-China military coalition on China’s near-seas. Given the maritime nature of these threats, China has dedicated more resources to modernising and restructuring its navy and air force.

Historically, the South China Sea has been used as an invasion route to invade China during the 1839 Opium War. The South China Sea serves as a strategic buffer zone for China to monitor the movement of foreign warships, and defend the mainland from attacks. In 2011, Obama’s “Pivot to Asia” intensified the US Navy’s Freedom of Navigation Operations in the South China Sea. In response to the US’s increased military presence, China accelerated island-building in the Spratly and Paracel from 2013 to 2015. The PLA then deployed Anti-Access Area Denial (A2/AD) systems such as Anti-Ballistic Ship Missiles (ABSMs), Surface-to-Air Missiles (SAMs), and fighter jets on the islands, which can obstruct the US navy’s manoeuvres during conflicts (Zenel, 2019).

Taiwan also poses a security threat to China due to its geographical proximity, which may provide a base for adversaries to attack China (Kissinger, 2012). Furthermore, foreign interference and independence movements in Taiwan have generated fears that Taiwan may seek independence, which could lead to a conflict. For instance, in the lead up to the 1996 Taiwanese Presidential Elections, China fired missiles into the Taiwan Straits to warn Taiwan against seeking independence. In response, the US sent two aircraft carriers through the Taiwan Straits and China was unable to retaliate militarily, thereby raising concerns that Taiwan may use US protection to secede. Since then, China has ramped up naval and air force modernisation and restructuring to prevent Taiwanese independence and deter foreign interference. According to Taiwan’s Defence Ministry, China’s advanced air, naval and missile capabilities could “paralyse” Taiwan’s defences, making it vulnerable to a Chinese attack (Reuters, 2021).

While the realist logic of consequences is valid, I opine that Xi’s strong sense of responsibility for defending China’s “Core Interests” undergirds his vision to transform the PLA into a “World-Class” military by 2050. Buzan and Waever (1998) define securitisation as a process whereby actors determine threats to national security based on subjective rather than objective assessments. Securitisation occurs when actors politicise issues and successfully convince the public of the urgency of the threats faced. Although the “Century of Humiliation” has been used to securitise China’s territorial disputes since the 1990s, there has been an intensification under Xi Jinping. Since 2012, Xi has used the term “Century of Humiliation” during key speeches, such as the 2015 70th anniversary of the end of World War Two, 2017 19th Party Congress, 2019 70th anniversary of the founding of the PRC, and the 2021 Centenary of the founding of the CCP. According to Dickson’s 2016 study, close to 80% of Chinese respondents agreed that China was defeated in the Opium War due to its “backwardness.” Public support for Xi’s vision for a strong military to defend China’s “Core Interests” has legitimised and mobilised resources for China’s military modernisation and restructuring.

Defending China’s Global Economic Interests

China requires a military that can project its power to defend its global economic interests, which necessitates military modernisation and restructuring. China is the world’s largest trading country accounting for 13% of global trade, and export-oriented industries employ 30% of China’s workforce (UNCTAD, 2021). Additionally, China is the world’s largest importer of natural resources and commodities, which power China’s economy. For example, in 2017, China surpassed the US to become the largest oil importer, importing 8.4 million barrels of oil per day (EIA, 2018). Most of China’s economic trade is conducted through the seas, which could be severed in times of conflict. In 2003, Hu Jintao noted that the closure of the Malacca Straits would undermine China’s access to global markets and commodity imports (Storey, 2006). Moreover, geopolitical tensions in the Gulf could cause fluctuations in oil prices, affecting China’s energy security, and piracy causes billions of dollars of losses for Chinese shipping annually.

Besides sea trade, China has expanded its economic presence through the BRI which opens new export markets while ensuring a stable supply of natural gas and oil, and allowing China access to the Indian Ocean. According to the Council on Foreign Relations (2020), China has spent more than $200 billion on infrastructural projects on the BRI since 2013. However, the BRI faces threats from non-state actors such as terrorists, which could undermine the BRI’s progress. In August 2021, 9 Chinese workers were killed in a suicide bombing in Gwadar, a key port in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Additionally, an unstable Afghan government could upset Chinese plans to invest in lithium extraction, which is an essential material for the production of electronic components.

China has restructured the PLA to overcome these threats through focusing on counter-terrorism, and counter-piracy operations:

- Counter-terrorism: China has conducted counter-terrorism military drills with the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) to improve military coordination, and signal China’s determination to safeguard regional peace and stability. For instance, in September 2021, China and the SCO participated in the “Peace-Mission 2021” live firing drills in Russia in response to the US withdrawal from Afghanistan.

- Naval Modernisation and Counter-Piracy: China has participated in counter-piracy operations and exercises in the Indian Ocean since 2008. In February 2021, China sent its latest guided-missile destroyers and frigates to partake in the multilateral counter-piracy Exercise Aman.

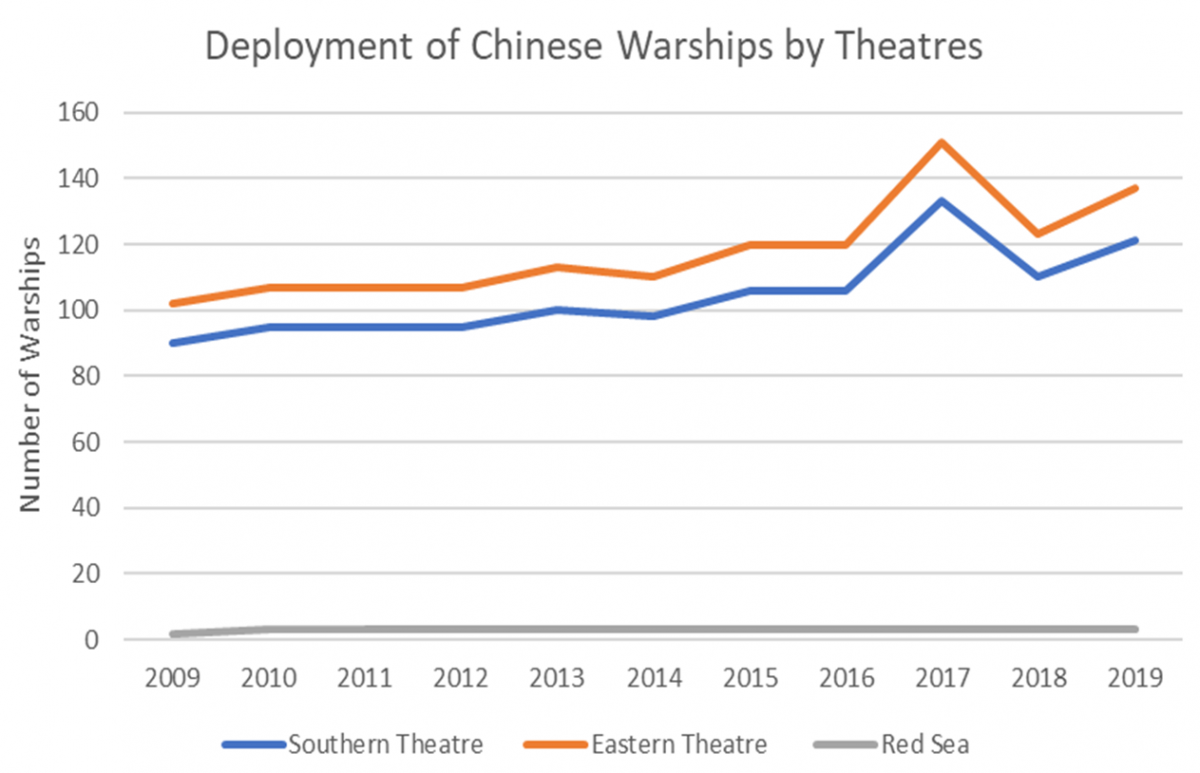

Despite China’s growing economic interests globally, I argue that China is still focused on defending its sovereignty in the South China Sea and Taiwan as most of China’s naval warships are concentrated in China’s Eastern and Southern Joint Theatre Commands (See Annex C). As such, China’s counter-piracy operations and counter-terrorism drills serve other purposes, such as reinforcing China’s “responsible power” status, rather than protecting China’s economic interests. Although China’s growing global economic interests does contribute to China’s increased military budget, it is not the main driver influencing China’s military modernisation and restructuring.

Conclusion

China’s military modernisation and restructuring is a complex endeavour involving personalities, domestic politics, foreign relations and the economy. Realism focuses on the role of power in explaining China’s military modernisation and restructuring, whereas the Interpretative Actor Perspective analyses how leaders’ thoughts and motivations can drive military transformation. However, realism does not account for why China’s military reforms only became more apparent in the past decade as compared to the period up to 2010. Instead, the Interpretative Actor Perspective of Xi’s ambitions, sense of responsibility and assertive leadership allows him to reconstitute social facts and implement military reforms to achieve a “World-Class” military by 2050. Xi has controlled the CMC decision-making processes, consolidated the MR systems into Joint Theatre Commands, and refocused China’s attention on the Navy, hence, raising the PLA’s operational readiness. Furthermore, Xi’s personal interest in military reforms have made China a regional power capable of responding to the US’s military might.

Despite China’s recent efforts at military modernisation and restructuring, it is unlikely to close the military technology gap with the US soon as the US remains the world’s leader in emerging technologies and military R&D spending, giving the US a technological edge over China. However, Xi’s vision of becoming a world’s leader in robotics, AI and semiconductors has mobilised intellectual and material resources to rapidly developing these technologies for potential military purposes. In the long term, China’s large economic base and talent pool would eventually allow China to surpass the US militarily and achieve Xi’s vision of a “World-Class” military by 2050.

References

Allen, K., Blasko, D. & Corbett, J, F. (2016). The PLA’s New Organisational Structure: What is Known, Unknown and Speculation (Part 1). Jamestown Foundation China Brief Volume 16(3).

Bullard, M, R. & O’Dawd, E, C. (1986). Defining the Role of the PLA in the Post-Mao Era. Asian Survey, 26(6), 706-720.

Buzan, B., Waever, O., de Wilde, J. (1998) Security: a New Framework for Analysis. Lynne Reinner, Boulder.

Brookings Institute. (2020). Signing Up or Standing Aside: Disaggregating Participation in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Retrieved, 13th October 2021, from https://www.brookings.edu/articles/signing-up-or-standing-aside-disaggregating-participation-in-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative/.

Carlsnaes, W. (1992). The Agency-Structure Problem in Foreign Policy Analysis. International Studies Quarterly, 36(3), 245-270.

Char, J. & Bitzinger, R, A. (2017). A New Direction in the People’s Liberation Army’s Emergent Strategic Thinking, Roles and Missions. The China Quarterly, 232, 841-865.

Council on Foreign Relations. (2020). China’s Massive Belt and Road Initiative. Retrieved, 13th October 2021, from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-massive-belt-and-road-initiative.

Dickson, B, J. (2016). The Survival Strategy of the Chinese Communist Party. The Washington Quarterly, 39(4), 27-44.

EIA, (2018). China Surpassed the United States as the World’s Largest Crude Oil Importer in 2017. Retrieved 13th October 2021, from https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=34812.

Foreign Policy. (2019). Xi Jinping Knows Who his Enemies are. Retrieved, 13th October 2021, from https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/11/21/xi-jinping-china-communist-party-francois-bougon/.

Fravel, T, M. (2020). China’s “World-Class Military” Ambitions: Origins and Implications. The Washington Quarterly, 4(1), 85-99.

Hollis, M. & Smith, S. (1990). Explaining and Understanding International Relations. Oxford University Press, 164-167.

Hart, B., Glaser, B, S. & Funaiole, M, P. (2021). China’s 2027 Goal Marks the PLA’s Centennial, Not an Expedited Military Modernization. Jamestown Foundation China Brief, 21(6).

IISS. (2021). China’s New Five-Year Plan and 2021 Budget: What do they Mean for Defence. Retrieved, 13th October 2021, from https://www.iiss.org/blogs/analysis/2021/03/chinas-new-five-year-plan-and-2021-budget

Jencks, H. (1992). Chinese Evaluations of “Desert Storm”: Implications for PRC Security. The Journal of East Asian Affairs, 6(2), 447-477.

Kamphausen, R., Lai, D. & Tanner, T. (2014). Assessing the People’s Liberation Army in the Hu Jintao Era. United States Army War College Press. 207-256.

Kissinger, H. (2012). On China. Penguin Books.

Liao, N, C, C. (2016). China’s New Foreign Policy Under Xi Jinping. Asian Security, 12(2). 82-91.

Lowsen, B. (2021). China’s Updated National Defense Law: Going for Broke. Jamestown China Brief, 21(4).

Li, N. (2018). Party Congress Reshuffle Strengthen Xi’s Hold on Central Military Commission. Jamestown Foundation China Brief, 18(3).

Mearsheimer, J. (2001). The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. Norton.

Nikkei. (2021). Full Text of Xi Jinping’s Speech on the CCP’s 100th Anniversary. Retrieved, 13th October 2021, from https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Full-text-of-Xi-Jinping-s-speech-on-the-CCP-s-100th-anniversary.

RAND Corporation. (2017). The US-China Military Scorecard. Retrieved, 13th October 2021, from https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR300/RR392/RAND_RR392.pdf.

Shan, W. (2016). Xi Jinping’s Leadership Style. East Asian Policy, 8(3), 42-53.

Storey, I. (2006). China’s “Malacca Dilemma.” Jamestown Foundation China Brief, 6(8).

US Department of Defence. (2020). China Military Power Report. Retrieved, 13th October 2021, from https://media.defense.gov/2020/Sep/01/2002488689/-1/-1/1/2020-DOD-CHINA-MILITARY-POWER-REPORT-FINAL.PDF.

UNCTAD. (2021). China: The Rise of a Trade Titan. Retrieved, 13th October 2021, from https://unctad.org/news/china-rise-trade-titan.

Waltz, K. (1979). Theory of International Politics. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 102-128.

Xinhua. (2019). Full Text: China’s National Defence in the New Era. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-07/24/c_138253389.htm.

You, J. (1999). The Revolution in Military Affairs and the Evolution of China’s Strategic Thinking. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 21(3), 344-364.

You, J. (2018). Xi Jinping and PLA Transformation Through Reforms. RSIS Working Papers.

Zenel, G. (2019). China’s Military Modernisation, Japan’s Normalisation and the South China Sea Territorial Disputes. Springer Books.

Appendix

Annex A

Source: Merics Mercator Institute for China Studies

Annex B

Source: CFR and Stockholm International Peace Research Institute

Annex C

Source: US Department of Defense, 2009-2019

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Shaping the Transnational Capitalist Class: TNCs and the Global Economy

- China’s Increasing Influence in the Middle East

- Friend or Foe? Explaining the Philippines’ China Policy in the South China Sea

- Can China Continue to Rise Peacefully?

- To What Extent Has China’s Security Policy Evolved in Sub-saharan Africa?

- Why China Should Re-Strategize its Wolf Warrior Diplomacy