Despite decades of division, the assumption remains that Korean unification will occur. However, this overlooks important aspects of what unification will look like and the willingness of South Koreans to acclimate to such a drastic change. After decades of hostility from the North Korean government, there may be lingering biases against former North Korean citizens even with unification. The massive income disparity may not only play a role in South Koreans’ willingness to support a unification for which they will be held financially responsible, but may also shape views of North Koreans more broadly. Additionally, the quality of the education systems in each country differs on such a scale that many North Korean arrivals struggle to find jobs in South Korea for their very limited skill sets. This raises the question: how unified would Korea really be when deep divisions on identity endure?

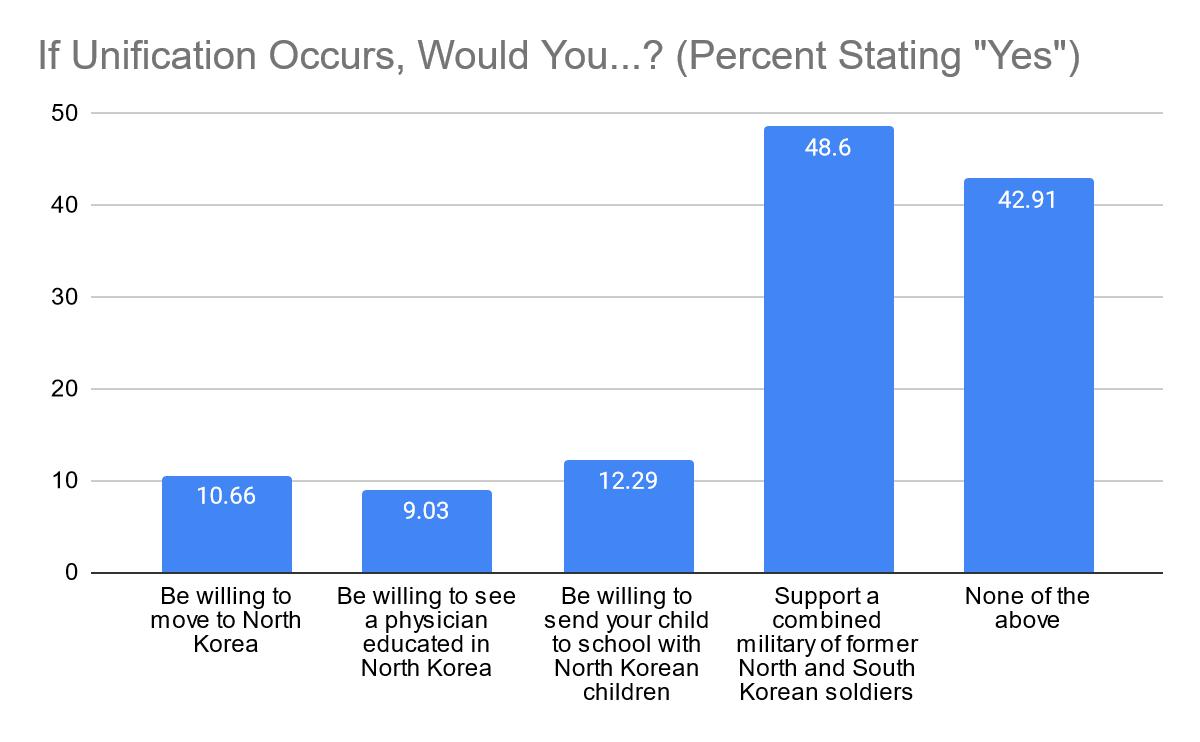

We conducted an original web survey to gauge South Korean willingness for different aspects of social and structural integration if unification occurred. Administered by Macromill Embrain from March 11-16, 2022, and with quota sampling on age, gender, and region, we asked 1,107 South Korean citizens ‘if unification occurs, would you be willing to…

- move to North Korea

- see a physician educated in North Korea

- send your child to school with North Korean children

- support a combined military with former North and South Korean soldiers

The data (see below) suggests South Koreans would hold less than favorable views of North Koreans in a post-unification scenario. First, 42.91% of respondents were unsupportive of any of the four post-unification scenarios proposed, providing further evidence for the claim that South Koreans will remain cautious if not distrustful of North Koreans. Additionally, while a 10.66% of survey respondents said they would be willing to move to North Korea, a mere 9.03% would see a physician educated in the North, and just 12.29% would allow their children to attend school with a North Korean child. When broken down by gender, we generally find men more willing to do all four proposed integration items, the most notable differences on moving (14.36% vs. 7.01%) and on a combined military (52.81%), while 48.38% of women were not supportive of any of the four measures, compared to 37.39% of men. Such low rates contrast with decades of survey data that suggest general favorability towards eventual unification. In fact, our results find that even among those that claimed support for unification, three quarters or more were unwilling to do the first three activities proposed. The results also suggest the importance of moving away from abstract support for unification, itself likely propped in part due to social desirability biases, towards explicit actions and policies that would impact the daily lives of South Koreans post-unification.

In his book Preparing North Korean Elites for Unification, Bennett specifically mentions that physicians will be an important group to co-opt post-unification. However, according to the data, that may be a politically difficult task. North Korea’s medical system is ill equipped and understaffed. The fundamentals of medicine are unlikely to differ across the demilitarized zone (DMZ); however, people may be uneasy about seeing physicians that have not worked with contemporary practices or worked in less than optimal conditions where the patients provide their own tools. In addition, unification will result in an influx of new patients seeking serious medical care. Therefore, South Korean officials will have to work harder to help these individuals transition, helping to decrease the deficit of medical professionals. One possible solution would be that the South Korean government and NGOs could help by providing instructors and paying for the “updating” of North Korean medical practice.

Unification could also lead to more issues in the future regarding education and the workforce. If South Koreans are not willing to send their children to school with North Koreans or move to North Korea, their education will not be at the same level, with the poorer North having to rebuild their education system. However, this could get better over time, seeing that, according to our own survey, that over half of South Koreans said that they would be comfortable with the integration of North Koreans in the workforce, marrying into South Korean families, and living in the same vicinity.

In addition to the possible lower level of education, many South Koreans believe that it is important to abide by the South Korean political and legal system in order to be considered Korean (about 93.4%). Especially considering North Korea’s historically hostile relations, as well as a growing sense of civic identity over a purely ethnic conception of the nation, South Koreans after unification may not accept North Koreans as the same.

In regards to how this could play out, reunification in Korea could learn from German reunification. In Germany, only 41% of East Germans believe that their lives have improved since reunification. Many East Germans also face second-class status in reunified Germany. This kind of issue could also occur in a unified Korea, especially considering that many South Koreans would not be willing to send their children to school with North Korean children, nor go to a North Korean physician.

Surprisingly, 48.6% of respondents supported the combination of North and South Korean armed forces, with slightly higher rates among men (52.81%). This may be a function of both male experience with conscription and its declining support among the population. In a survey taken by Gallup Korea in 2021, 42% of participants indicated support for conscription, which is nearly six points lower than in 2016 and fourteen points less than in 2014. South Korea is also rapidly approaching a point where there will be a deficit between conscripts needed and those who are eligible. Voters and politicians of both major parties have become more supportive of military reform. This would include measures such as an all-volunteer force and allowing women to take part in conscription. It is very possible that South Koreans could see a combined force as a way to end the need for conscription altogether or fill future holes in personnel, especially as the perceived main threat for South Korea would no longer be North Korea.

Post-unification, one of the most important issues that South Korean officials will have to deal with will be the way they handle the North Korean army. With nearly 1.28 million active-duty personnel, a dismantled North Korean army could mount an insurgency movement in the North. One solution proposed by Bennett is to co-opt much of the leadership of the North Korean military. Considering that most North Korean men spend much of their lives in the military, a combined force could be a stepping-stone to civilian life in a newly unified Korea. While older members may see unification as a time to retire, younger professionals may see it as a way to move up. As this survey indicates, there is already a strong base of support across parties to build from.

Our survey results highlight the need to reevaluate preparation for unification and conceptualize it not just as the end of conflict, but also as the start of new sources of tension. Despite support in general for unification, these tensions could impact diverse areas from the military to education, health care and others that we did not directly address in the survey. Unification will change core aspects of Korean life and should promote policies that can help mitigate these tensions, rather than letting these issues to simply solve themselves over time.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Would You Hire A North Korean? South Korean Public Opinion is Mixed

- Why are South Koreans So Opposed to Accepting Refugees?

- Opinion – The Potential of Strategic Ambiguity for South Korean Security

- Surveying Opinion on Withdrawing US Troops from Afghanistan and South Korea

- A Unified Korea: Good for All (Except Japan)

- The Emperor’s Dignity: A Candid Primer on Korean Reunification