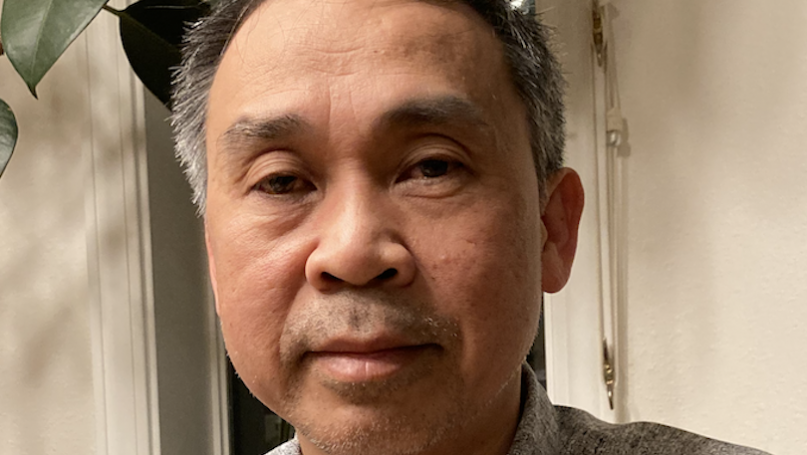

Tuong Vu is director of Asian Studies and professor of Political Science at the University of Oregon, and has held visiting appointments at Princeton University and National University of Singapore as well as taught at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, CA. Vu’s research and teaching concern the comparative politics of state formation, development, nationalism, and revolutions, with a particular focus on East Asia. He is the author of two books on the politics of development, state formation, and revolution in East Asia as well as the co-editor of six books on Southeast Asian politics, the Cold War in Asia, the Republic of Vietnam (1955-1975), Vietnamese republicanism, contemporary Vietnamese politics and economy, and the Vietnamese American community. Among his works are Vietnam’s Communist Revolution: The Power and Limits of Ideology (Cambridge, 2017), Paths to Development in Asia: South Korea, Vietnam, China, and Indonesia (Cambridge, 2010), Dynamics of the Cold War in Asia: Ideology, Identity, and Culture (Palgrave, 2009), and Southeast Asia in Political Science: Theory, Region, and Qualitative Analysis (Stanford, 2008).

Where do you see the most exciting research/debates happening in your field?

I work between fields, subfields, regions, and topics, whether it is comparative politics/international relations; political science/history; political economy/political sociology; East Asian/Southeast Asian studies; Vietnamese communism/republicanism; Vietnamese history/Vietnamese American history. In the last five years or so, my work has focused on three distinct topics, including the imperial origins of the modern nation-state order in East Asia; the relationship between radical revolutions and the global order; and Vietnamese republican history and politics. For my first two topics, I have followed scholarship in International Relations, I’m excited by the works that excavate historical trends (such as Fukuyama 2011; Zarakol 2011), or that take ideologies and identities seriously (Phillips 2011; Phillips and Reus-Smit 2020), or that compare empires (Go 2011), or on state-formation and nation-building (Matsuzaki 2019).

How has the way you understand the world changed over time, and what (or who) prompted the most significant shifts in your thinking?

As my scholarship evolves, I have come to look beyond (existing) national borders and adopt transnational and global perspectives. I have learned tremendously from the field of International Relations, yet feel that the field is limited by its fixation on (modern) national borders, which is reflected in the very term “international.” When I study the relationship among premodern polities, which were mostly empires, I found out that the term “international” is misleading, but the term “interimperial” does not even exist in most dictionaries.

I’m interested in state formation as a historical process, much of which took place before the emergence of modern nation-states. I also study modern nationalist and communist movements and revolutions from a discursive and ideological perspective. My study of these topics and my approaches make me appreciate the transnational nature of politics as well as the work of activists to create a discourse of their nations that often did not match modern borders.

How similar are the economic policies of People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV) and where do we see the greatest divergences? Is the SRV’s socialist-oriented market economy fundamentally different to the PRC’s socialist market economy?

The PRC and SRV have embarked on broadly similar policies to gradually abolish central planning, remove restrictions on markets from land to labor, and promote domestic and foreign trade and export. Major differences between the two can be traced to their starting point. Firstly, in China the pre-reform state was much more effective than its Vietnamese counterpart, and this has continued with the Chinese state playing a much more effective role in guiding the reform process. Among other things, state effectiveness has enabled China to more successfully promote domestic industries and technological transfers from foreign firms.

Secondly, Chinese market reform was built on a much higher level of industrial and technological development, and technocrats have had greater power in formulating economic policies in China. Vietnam has been counting much more on foreign remittance and investment, and its economy relies mostly on low-skilled labor and is far more trade-dependent.

Thirdly, due to the Sino-Soviet conflict in the 1960s-1970s, China’s socialist economy and state before reform had little or no relationship with the Soviet bloc. The Chinese were also deeply disillusioned with communism due to the Cultural Revolution. In contrast, Vietnam’s ties to the Soviet bloc during the Cold War were strong as Vietnam was heavily dependent on the bloc’s aid in the 1980s. Ideological resistance to market reform among Vietnamese leaders has been stronger than in China as a result. Although Vietnam’s reform has benefited much from southerners who had lived in a capitalist economy during the 20 years when Vietnam was divided, but northerners still control politics and do not allow faster reforms.

Finally, as a result of Vietnam’s close relations with the Soviet bloc before reform, Soviet-trained scholars still dominated Vietnamese universities until recently. In contrast, China sent thousands of students to the US after relations were normalized in the late 1970s. The educational system and especially universities in Vietnam have been modernized very slowly, leading to not only the phenomena of brain drain and “educational refugees” but also a labor force with low productivity. Vietnam faces a much greater likelihood of being trapped in the middle-income group of countries.

Western commentators have often attributed China’s and Vietnam’s successes to market liberalisation and the embracement of capitalism while maintaining a socialist facade. Do you agree with this assessment or are they still committed to their respective forms of Marxism-Leninism?

Much depends on how one defines “success.” If it means orderly changes, yes. If it means success in the same way as South Korea and Taiwan which has undergone not only industrialization but also democratization, no. Perhaps China may be able to industrialize in the next couple of decades, but that prospect is still unthinkable for Vietnam after thirty years of reform. Furthermore, I would argue that there is much more than a socialist façade with the public ownership of land and with the state sector still under the control of the communist party and having the dominant role in the economy. The political system retains much of the Leninist state structure with overlapping and extensive bureaucracies of party, state, and mass organizations controlling not only political but also economic, social, and cultural life down to the neighborhood and village level. Loyalty to Marxism is still enforced in propaganda and education.

To what extent have state-owned enterprises played a role in East Asian economies?

State-owned enterprises have played important roles in some East Asian economies such as Taiwan and Indonesia. They play minor roles in other capitalist economies such as Malaysia and Singapore. For China and Vietnam, they still dominate the strategic sectors of the economy and enjoy substantial advantages, as vehicles for patronage and symbols of socialism.

Vietnam, South Korea, Singapore, China, and Taiwan either industrialised or are industrialising under authoritarian political systems. Is an initial or permanent lack of democracy a prerequisite for their economic success?

The answer is no. Scholars have searched in vain for a systematic theoretical relationship between democracy and economic success, and the question can only be answered for specific cases. Again, much depends on how one defines “success.” There is a huge gap between the economic “success” of Vietnam and that of Singapore or South Korea. After 30 years of market reform, Vietnam’s level of development today still can’t be compared to that of South Korea in 1980, for example.

There is also a huge difference among the political systems of the above countries. South Korea and Singapore have always more or less allowed opposition parties and a private press – these regimes were/are authoritarian but their people have enjoyed far more civil liberties than the Vietnamese and Chinese have. Even though Singapore is authoritarian, the rule of law there is quite advanced, whereas it doesn’t quite exist in Vietnam today.

South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore have also not been constrained by any ideologies. Their anticommunism imposes a very narrow limit on intellectual freedom: anything is fine as long as it’s not communism (and Islamism for Singapore). For Vietnam, in contrast, no ideology is acceptable except communism, at least in public. Vietnam is not just an authoritarian but a monotheist theocracy in this sense. I know doctoral students from Vietnam who received funding from US universities have turned them down if they also received government funding: the latter would require them to return to Vietnam, but if they return, they would not be treated with suspicion as those who were funded by US universities. I would argue that this monotheist-theocratic aspect has seriously limited Vietnam’s potential to be like South Korea.

What misconceptions do you believe western observers have about one-party rule or one-party dominant systems as practiced in various East Asian countries?

Western observers have often failed to understand the differences in economic and political systems between, on the one hand, Singapore, Malaysia, Japan, and South Korea, and on the other, China and Vietnam, as I have explained above. Convenient labels such as “one-party rule” significantly underestimate the legacies of totalitarianism in communist countries like China and Vietnam even three or four decades after market reform.

What lessons do you think developing countries can learn from East and Southeast Asia’s rise since the 1960’s?

The main lessons are the need to have a lean and effective state, a strong technocratic core of the bureaucracy, a dynamic private sector, basic civil rights including private property rights, the rule of law (not necessarily liberal in all aspects), a legal framework for some degree of political opposition and dissent, and for an independent private media to keep the ruling party constantly on guard.

What is the most important advice you could give to young scholars of International Relations?

I have benefited from looking beyond the field of International Relations in the US to read scholarship from the British tradition, for example. I also think it’s important for scholars of International Relations to develop regional expertise, especially a deep understanding of the language and culture of a certain world region. I have benefited enormously from my background in Asian studies.