For much of its existence, the discipline of International Relations (IR) has viewed nation-states as the key actors in global affairs. Gradually, however, scholars of IR and diplomacy have turned their attention to non-state actors such as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), multinational corporations, civil society, and the role of citizens. Recently, scholars have paid more attention to the role of cities as global actors, leading to a new and burgeoning subfield of city diplomacy that spans the fields of IR and urban studies (Amiri & Sevin, 2020; Curtis, 2016; Marchetti, 2021; Van der Pluijm and Melissen, 2007, p. 5-8). Recent studies have focused on the expanding role of city networks such as C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group and Mayors for Peace in global affairs (Acuto, 2013; Bouteligier, 2012), the role of cities as global activists (Miyazaki, 2021), the attractive agency of cities as the hubs and nodes of globalization (Curtis, 2011, 2016; Acuto, 2013; Curtis & Acuto, 2018), and the leadership of individual mayors as global actors (Acuto, 2013; Beal & Pinson, 2014; Stren & Friendly, 2019; Miyazaki, 2021).

The study of city diplomacy is still a relatively young subfield. Yet, a great deal of progress has been made in theorizing cities and their activities. This short essay details some of that progress, and advocates for future research that is eclectic, humble, and works in partnership with practitioners to find best practices. This essay also finds evidence that city diplomacy should not be idealized as a panacea to 21st-century problems. Though recent activities have shown that cities can respond more flexibly to issues of global concern such as climate change and nuclear disarmament in ways that may be difficult for states, cities too must deal with a kind of “realism” (different from tradition IR Realism) – the constraints of budgets, a lack of time, a lack of expertise, and the pressing needs of local constituents.

Theorizing Cities as Global Actors: A Case for Eclecticism and Humility

How do cities act? Why do cities act?How can we understand cities as actors? How do cities act in relation to states, IGOs, NGOs, and citizens? Theorizing about cities has been a troublesome affair, frustrated by the enigmatic and wonderful differences of individual cities, their relative invisibility in the scholarship until recently, and the different theoretical persuasions of authors writing about them. Thus, when it comes to theorizing the city as a global actor it is important to approach the project with a sense of humility. This humility can be deepened by several observations.

First, cities have important differences from states. Whereas states have fixed borders, rigorously defined and defended, cities tend to be more porous and subject to unregulated flows; in addition, their status as diplomatic actors is less defined and fluid. In important ways, they are free of the burdens of states but also limited by their ambiguous formal status in global affairs. Second, whenever we discuss a city, we should recognize the difficulty of discussing it as a unitary actor. Traditional IR, especially realist perspectives, have privileged examinations of states as unitary actors. Cities pose particularly thorny problems for unitary actor approaches (Acuto, 2013, p. 10). Should a city be treated as a unitary group, expressing a collective identity; or, should cities be treated as conduits and aggregations of people, goods, ideas, and events, or (to borrow a term from urban geography) the site of “flows”?

For these reasons, I believe the best approach to theorizing about cities at the moment is to be eclectic, humble, and grounded in concrete examples. Such an approach would avoid grand theories that can be generalized across many cases and instead develop “mid-range theories” (Sil & Katzenstein, 2010, para. 20) that seek to explain a smaller sample of similar cases. This approach should also attempt to provide insights for practitioners. A reciprocal relationship with practitioners is necessary because without access to their experiences, we are left with but the shallowest insights from afar.

Cities as Multi-Scalar Actors

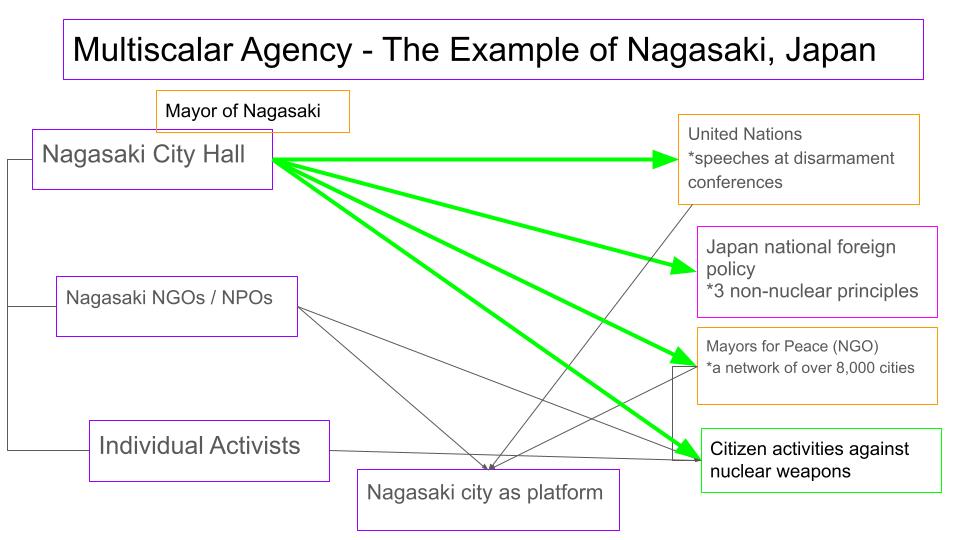

A key theme that spans the entirety of the literature is that the agency of cities is flexible and adaptable, working at multiple scales (see, for example, Acuto, 2013; Marchetti, 2021; Kwak, 2020, April 21). Cities network with other cities. They can engage United Nations bureaucracies and forums. They can form their own independent organizations or work with NGOs, activist groups, and powerful individuals. They can use international engagement to enhance their branding or they can choose to remain in the background on important issues. At times cities mimic the actions of states, engaging in conferences and summits not unlike those of states (for a conspicuous example, see the Urban 20). At other times, they mimic the actions of civil society actors. By establishing formal organizations with independent secretariats, they empower actors – not unlike IGOs – to act on their behalf. Though these actions make it hard to generalize about the actions of cities, they do open up a space to discuss best practices.

The illustration below demonstrates the concept of multi-scalar agency through the example of the city of Nagasaki, Japan. In the illustration, we can see how the diplomatic activities of the city emanate not only from city hall, but are also distributed through many different actors – the mayor, NGOs, and citizens – all of whom interact with one another in different ways. We can also see how these interactions influence ideas and discourse at the international, national, and local levels. (For more information on Nagasaki’s city diplomacy, please see Miyazaki (2021) and Meyer et al (2022)).

The Varying and Various Commitments of Cities

As Acuto et al (2016) found, city engagement in international affairs is most effective when it is strategic, has a dedicated team of professionals, and is consistent. Yet, city commitments to international affairs often vary widely by individual mayors (see also, Stren & Friendly, 2019; Miyazaki, 2021). This has led various authors to examine when and why mayors decide to “go global” (Beal & Pinson, 2014; Stren & Friendly, 2019; Marchetti, 2021, p. 63-67; Van der Pluijm & Melissen, 2007, p. 14-15). Motivations can vary widely from historical reasons, city identity, city branding, a desire for prestige, economic and social reasons, governance concerns, or simply the idea that it might help win an election. Another largely unexplored motivation might be peer competition / pressure. Mayors may join city networks or establish sister city relationships simply because they see other mayors do it.

With, Against, or Substitute for State-Diplomacy

City diplomacy can oppose the state, enhance the state, or serve as a substitute for state-level diplomacy. City diplomacy can enhance state diplomacy, as for example the way Chinese sister city relationships work to support the Belt and Road Initiative (see Marchetti, 2021, p. 55-56; Han et al, 2021). City diplomacy can also work against states, as when a group of sixty-one U.S. mayors affirmed their commitment to the Paris Climate Agreement to reduce carbon emissions, despite the withdrawal from the agreement by the Trump Administration (see Marchetti, 2021, p. 56-57; see also, Leffel, 2018). This movement would eventually grow into the organization Climate Mayors which now has over 470 member cities. Finally, there are important examples of when city diplomacy serves as a substitute for state-level diplomacy. This phenomenon is especially prominent in examples of failed states or in places where the national government does not enjoy official recognition. One such example is the Nicosia Initiative, a project where the European Committee of Regions works with Libyan cities to help provide better services such as waste management and health care by building capacities from the ground up (European Committee of Regions, n.d.; Marchetti, 2021, p. 97).

Sovereignty-Free Do-Gooders or Hard-Nosed Realists

An important observation in the scholarly literature is that, in contrast to states, cities tend to be “sovereignty-free” (Chan, 2016, p. 138; Rosenau, 1990). In other words, free from responsibilities for territorial defense and securing borders, cities can fill gaps in governance and work on issues that citizens are passionate about. On the surface, we can say that cities have practical, ground-level proficiencies, have more intimate relationships with their residents, and are more aspirational at times than their national counterparts. This has led authors such as Chan (2016) to argue that cities are the best hope for cosmopolitan democracy.

It is important, however, to avoid idealizing city-based solutions to global problems. Though the “Realism” of IR theory does not always apply to cities, a different type of realism often does. This realism is grounded in the pressing needs of local governance, such as the need for policing, health care, education, and garbage disposal. Some cities may not have staff trained in foreign affairs, significant budgetary resources, or the time to engage issues that their citizens feel passionate about. Pursuing an international initiative often means directing precious time and resources away from other pressing local issues (Beauregard & Pierre, 2000, p. 471; Marchetti, 2021, p. 70; Curtis & Acuto, 2018, p. 7). Even cities fortunate enough to have dedicated international affairs staff members must be realistic. As Nina Hachigian (2019, April 29), the Deputy Mayor for International Affairs of Los Angeles, has written, “City diplomacy must, first and foremost, serve the core purpose and objective of local government: to improve the lives of residents” (para. 4). This means that city diplomacy must often focus on agendas that bring tangible economic benefits to the city, such as trade and tourism, over more aspirational goals.

This “realism” with regards to the international role of cities is best articulated by Beauregard & Pierre (2000) who argue that not only should scholars be careful about how they assess the international capacities of cities, but they should also be careful not to cast city involvement in international affairs as automatically desireable or achievable. The authors write, “In a radical departure from conventional wisdom, we counsel a more conservative approach to international initiatives and resistance to the temptation of globalisation” (Beauregard & Pierre, 2000, p. 475). Thus, in contrast to the usual cosmopolitan mantra of our age, many cities may feel they have little choice but to think local, act local, and resist calls for greater global involvement.

Conclusion

A key theme that spans the entirety of the literature is that the agency of cities is flexible and adaptable, working at multiple scales. Cities network with other cities. They can oppose the state, enhance the state, and serve as a substitute for the state. They can engage with UN bureaucracies and speak authoritatively in their forums. They can form their own NGOs or work with NGOs, activist groups, corporations, and powerful individuals. They can use international engagement to enhance their branding or they can choose to remain in the background on important issues. Even when a mayor and city officials remain quiet on the international stage, the attractive power of the city can pull engagement toward it. At times cities mimic the actions of states, engaging in summits and conferences with other cities not unlike those of states. By establishing formal organizations with independent secretariats, they empower actors – not unlike IGOs – to act on their behalf. At other times, they mimic the actions of civil society actors.

Though the diversity of these actions makes it hard to generalize about the actions of cities, they do open up a space to discuss best practices. Scholarly authors have already begun to form important ideas about best practices (see Acuto et al, 2016, p. 24-25). Yet, there is still work to be done. What is the best path forward? Perhaps the best way to make progress is to build our theories from the ground up, asking first how we can be useful to the practitioners attempting to make city diplomacy work. Such an approach begins by building partnerships. Thankfully, that is a lesson that many working on the front lines of city diplomacy have already learned.

Bibliography

Acuto, M. (2013). Global Cities, Governance and Diplomacy. New York City, NY: Routledge

Acuto, M., Morissette, M., Chan, D., & Leffel, B. (2016). City Diplomacy and Twinning: Lessons from the UK, China and Globally. City Leadership Initiative, Department of Science, Technology, Engineering and Public Policy, University College London. UK Government Office for Science.

Amiri, S. & Sevin, E. (2020). Introduction. In: Amiri S., Sevin E. (eds) City Diplomacy: Current Trends and Future Prospects. Palgrave Macmillan Series in Global Public Diplomacy. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. (pp. 1-10).

Beal, V., & Pinson, G. (2014). When mayors go global: International strategies, urban governance and leadership. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(1), 302-317

Beauregard, R. A., & Pierre, J. (2000). Disputing the global: a sceptical view of locality-based international initiatives. Policy & Politics, 28(4), 465-478.

Bouteligier, S. (2012). Cities, Networks, and Global Environmental Governance: Spaces of Innovation, Places of Leadership. Routledge

Chan, D. K. (2016). City diplomacy and “glocal” governance: Revitalizing cosmopolitan democracy. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 29(2), 134–160.

Curtis, S. (2011). Global cities and the transformation of the international system. Review of International Studies, 37(4), 1923-1947.

Curtis, S. (2016). Cities and global governance: State failure or a new global order? Millennium – Journal of International Studies, 44(3), 455–477.

Curtis, S., & Acuto, M. (2018). The foreign policy of cities. The RUSI Journal, 163(6), 8–17.

European Committee of Regions. (n.d.). Nicosia Initiative Pioneering partnerships to promote decentralised cooperation with Libyan cities. Project Pamphlet.

Hachigian, N. (2019, April 16). Cities Will Determine the Future of Diplomacy. Foreign Policy.

Han, Y., Wang, H., & Wei, D. (2021). The Belt and Road Initiative, sister-city partnership and Chinese outward FDI. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 1-21.

Kwak, N. (2020, April 21). Municipalism is an Important Global Movement, and its History Matters. Diplomatic Courier.

Leffel, B. (2018). Animus of the underling: Theorizing city diplomacy in a world society. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 13(4), 502–522.

Marchetti, R. (2021). City Diplomacy: From City-States to Global Cities. University of Michigan Press.

Meyer, C., Cullis, S. & Clausen, D. (2022). Nagasaki’s global city diplomacy. East Asia Forum. January 5.

Miyazaki, H. (2021). Hiroshima and Nagasaki as models of city diplomacy. Sustainability Science, 16(4), 1215-1228.

Rosenau, J. (1990). Turbulence in World Politics: A Theory of Change and Continuity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sil, R., & Katzenstein, P. (2010). Analytic Eclecticism in the Study of World Politics: Reconfiguring Problems and Mechanisms across Research Traditions. Perspectives on Politics, 8(2), 411-431.

Stren, R., & Friendly, A. (2019). Toronto and São Paulo: Cities and international diplomacy. Urban Affairs Review, 55(2), 375-404.

Van der Pluijm, R., & Melissen, J. (2007). City Diplomacy: The Expanding Role of Cities in International Politics. The Hague: Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – A New International AI Body Is No Panacea

- Asset Revaluation and Beyond: Theorizing Climate Politics

- Indigenous Conflict Victims and the Growing Tent City in Bogotá

- Arab Contributions to Islamic International Relations: Why is There No Breakthrough in Theorizing?

- The Art of Diplomacy: Museums and Soft Power

- Xi Jinping’s Civil Diplomacy Initiative: Origins, Purpose, and Challenges