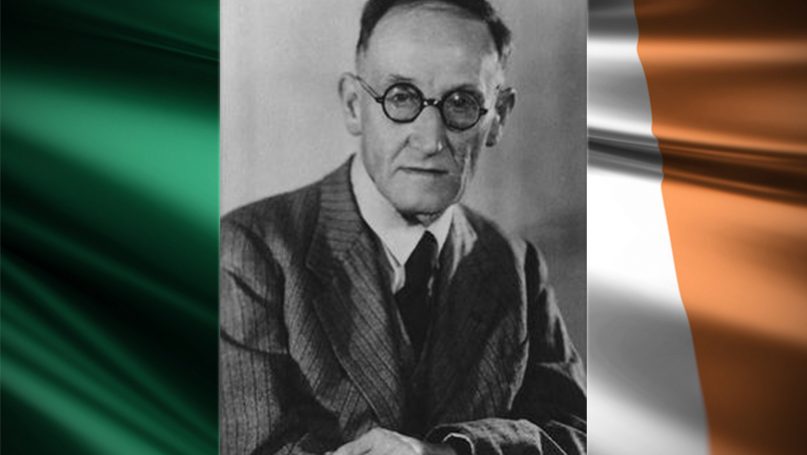

In the dark heritage of the fledgling Irish Free State’s efforts of administrative professionalization, few decisions could have been as reputationally consequential as the appointment to Ireland’s Museum Authority of Austrian Adolph Mahr. Records are to say the least sparing about Adolph, who was appointed Keeper of Irish Antiquities in 1927 and director of the entire National Museum by 1934. Looking back at the experience of the First World War in which countless Irish lives were lost in service of the British army, and at the political rancors of inter-war Europe, and even considering the subsequent political neutrality of the Free State, his choice as museums director looks puzzling. Adolph Mahr is a name seldom referenced – a Nazi (until now) rather concealed in the state annals.

Nor should it be overlooked that the Irish Free State fought conceptually with the museum authorities in Northern Ireland for supremacy of archaeological message. Dublin authorities hankered for a sense of Celtic identity while museum chiefs in the new state of Northern Ireland mentally willed to life the materialization of their Scottish cousins, around every Ulster crannog. Archaeologists on both sides of the border became increasingly professionalized as the century progressed, and everyone marveled the nomenclature of their finds. What ostensibly seemed Celtic was at times decidedly Ulster Scots, while that which was oft regarded as Scottish Baroque, on closer inspection yielded evidence of Celts. However, it is important to note that there was a political war between the respective museum experts, into which the malodorous racism of the South’s chief spokesman, Dr Mahr, was barely referenced by either side. It is something of a dark comedy that while this subterfuge of regional rivalry was being played out, Ireland’s museology was in the hands of a committed Nazi.

In this battle, Mahr was widely regarded, as “the father of Irish archaeology.” Whatever his personal politics, Mahr was a competent professional archaeologist who had unique Celtic expertise, and brought scientific methods to the field, such as implementing the Lithberg Report, which had been damning about the low previous standards across much of Irish museology. However, it was more than an open secret, that he was a committed and soon to become senior Nazi. And yet, distastefully, he was also the figurehead leading Ireland’s less than friendly museological rivalry with their opposite numbers in the museum authorities in Northern Ireland.

The Nazi party was specifically crafted to lure workers from communism and into völkisch nationalism. Its credentials, like those of Adolph, were unmistakably those of “A Nazi in plain sight”. Yet with the malodorous atmosphere of WW2 and the revelations of the colossal extent and barbarity of Hitler’s regime, Adolph Marr was conveniently forgotten, and certainly had no chance, post-war, of ever reclaiming his old job. Indeed, Adolph slowly found he could not be resuscitated, but he could indeed be forgotten. We owe much of our fragmented knowledge about Marr to Gerry Mullins who in 2007 published the volume, Dublin Nazi No. 1.

When he arrived in Dublin in 1927 to head up Irish Antiquities, Mahr was one of many foreigners head-hunted by the Free State. It was as if Dublin had an inferiority complex against picking their own and a marked distaste for experts from the old colonies. Mahr’s meteoric rise to lead Irish museology is less interesting than the fact that between 1934–39 he founded and commanded Ireland’s Nazis. He aggressively monitored the German community, acted as the eyes and ears of Germany, promoted the Nazi youth, and supported influential German interlocutors on state bodies such as the ESB and the Turf Board. Given the scarcity of professional talent, 1930s Ireland was probably an opportunistic time for someone like Mahr, but it is less easy to understand the official tolerance of his Nazism.

Mahr A Politicizing Museologist?

That Mahr was a civil servant in Ireland, begs the question why his politicizing was even tolerated? When war came, and with every intention of coming back to Ireland as he had a genuine obsession with all things Celtic, Mahr quickly led much of the German propaganda blasted to neutral Ireland. It should not be under-estimated that many Nazis metamorphosed in peacetime or underwent formal de-Nazification procedure. Mahr passed in 1951 in German obscurity without reprising his job. It has always been rumored that if the Nazis had invaded, Mahr would have been the obvious Nazi Gauleiter in an Irish satellite state. He did understand the Irish imbroglio very well, delicately crafting from Germany a subtle anti-imperial and anti-partition, pro-neutrality campaign, and cunningly exploiting Irish America. He also recognized that Ireland’s Jewish community were so sparse that antisemitism was all but irrelevant. Mahr was (however) devoted to a worldview based around Aryan superiority. His moral compass had no difficulty with the holocaust.

Mullins notes that Mahr, “comes across as an ardent anti-Semite in calling for anti-Jewish propaganda in foreign radio services” but that it is more noteworthy that he was the quintessential Nazi volunteer. He could have stood aloof from all that in Ireland, but instead he returned to be part of the Nazi fray. As Michael Gibbons observes, “he proudly served National Socialism, helped his Party overcome the perceived Jewish menace, and never questioned the Party’s ideology.” That must lead us to think a great deal less of him whether as a museum professional, a genuine exponent of Celtic studies or as a human being.

Born in the Hapsburg South Tyrol, Mahr’s was a military family of Sudeten Germans. They were abstemiously part of the German nationalist tradition within the Hapsburg empire. After army service in the Austrian army in 1906 attaining lieutenant rank, he studied at the University of Vienna, where he was a member of an avowedly antisemitic dueling fraternity. Indeed, a gunshot injury while dueling spared him from subsequent military service, and conceivably spared his life. After graduation, Mahr was employed by the Linz Museum, then the Vienna Natural History and Prehistoric Museum two years later; he eventually held the posts of curator and deputy director of the Anthropological-Ethnological Department. Economic hardship during the depression years fine-tuned his dislike of Jewry. From field archaeologist at the Iron Age Celtic graveyard in Hallstatt, Austria, Mahr successfully applied to join the National Museum of Ireland.

There was a well-developed German scholarly interest in Celtic studies. There was also an almost pathological desire on the part of the Irish state not to appoint Britons to state jobs, and so Mahr became part of the European “brain drain” that brought many to the inter-war Irish state. And, Mahr did prove his worth. He reorganized the museum’s collections in line with the Swedish Professor Nils Lithberg’s landmark antiquities report. He did decent work on designing a simple card index of excavations and succeeded in garnering funds from donors such as the Dublin-born California insurance magnate, Albert Bender (1866–1941), who donated a collection of Asiatic art to the museum. Ironically, Bender was a Semite. Mahr put his Germanic organizational acumen to use, streamlining excavation efforts. In 1931, when the Harvard Anthropological Study applied to conduct excavations in Ireland, the archaeological partner of the more famous Arensberg and Kimball study of wild Ireland, Mahr backed them. He and the Harvard archaeologists used the subsequent digs (1932–6) to skill up Irish scholars in modern excavation techniques. Mahr was also a reliable professional collaborator to colleague such as Belfast-based Emyr Estyn Evans. His scientific credibility as an archaeologist has never been doubted, but his moral judgement and respect for humanity inviolably are.

An Austrian enchanted by the Celts

The best surviving example of his Celtic Studies expertise is Mahr’s presidential address in 1937 to the Prehistoric Society, which was published in their Proceedings. In his address Mahr expertly synthesized the state of Irish archaeological knowledge based on his very meaningful collaboration with his Irish peers. This should be interpreted as a juxtaposition to a vision of Mahr as a Jew-hunting Nazi at large in the Irish countryside. Mahr also wrote on Irish archaeology in various eminent journals, including the Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, and with Joseph Raftery, authored the famous two-volume, Christian art in ancient Ireland (vol. i (1932) edited by Mahr vol. ii (1941) by Raftery). That first volume had been commissioned as part of the celebrations surrounding the 1932 Eucharistic Congress, which also gives an illuminating insight into Mahr’s capacity as an interlocuter with the Catholic hierarchy. In 1934 Mahr’s official endorsement by the Fianna Fáil government of Éamon de Valera elevated him to the prestigious national museum directorship.

When Hitler became German chancellor in January 1933, there was a mild but significant response in Ireland. Most adult Germans in Dublin, some five hundred or so, became Nazis. We can establish Mahr’s own “card carrying” credentials by 1 April 1933. It should also be observed that there was an implicit Germanic nationalism in German archaeology of the time, and Mahr was so imbued. To that extent we can understand Mahr’s view expressed in 1932, “the boundaries which separated humankind in the Stone Age are more important than the makeshifts of our present politicians”. Mullins further clarifies the significance of this statement in that German nationalists regarded their own views as transcending ‘politics’, which they saw as a futile distraction from the achievement of national unity and greatness). There is (however) no evidence whatsoever of Nazi rhetoric in his speechmaking or in any informal interaction with any Irish archaeologist at that time. He was “A Nazi in plain sight” but this did not impinge overtly on “his day job”. Indeed, several prominent archaeologists such as the Oxford classical scholar Paul Jacobsthal told Mahr’s denazification tribunal that his scholarly writings, “never defiled history by projecting racial or other doctrines of Nazism into the past”. His professional archaeology remained resolutely scientific, and there was no sense of Ireland’s Museums Service being in the hands of a blatant Nazi. To that extent. Mahr was able to hermetically separate these two roles.

Political Schizophrenia?

This leads one to the inevitable conclusion that Mahr was capable of simultaneously maintaining a “dual identity,” schizophrenically presenting as curator-technocrat while also moonlighting as Nazi chief, like a veritable Dr Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Mahr was the natural leader of the Nazi Party in Ireland, serving as the Ortsgruppenleiter and as head of the Irish division of the Auslandsorganisation, the association of Nazi Party members living abroad, which was led by Ernst-Wilhelm Bohle. Bohle operated a clandestine information-gathering agency which also promoted German overseas trade. Mahr reported back to Germany using a spy ring. Mahr’s home at 37 Waterloo Place, Dublin, was a social centre for the German community in Ireland; Mahr informed on German residents in Ireland (including Jewish refugees). He also demonstrated pragmatism in dealing with the unpleasant issue of antisemitism and even sometimes helped Jewish associates leave Germany. Never a vulgar ideologue, Mahr seems to have distinguished between his prejudices against ‘Jewry’ in general and his individual Jewish contacts, most of whom he had met through museology.

Ireland was neutral, but it should be noted that Mahr’s reportage could have precipitated a death warrant if Ireland been occupied by German forces. Indeed, the records show that one Julius Pokorny, when writing to a National Library employee about his plans to escape the Reich, urged him not to repeat them in case Mahr informed the Nazi authorities. Even the German legation was subject to pressure from the local Auslandsorganisation. In 1934 the departing German representative in Dublin, Georg von Dehn-Schmidt, was photographed kissing the ring of the papal nuncio during a courtesy call; the photograph was reproduced in Julius Streicher’s Der Sturmer, leading (amid widespread Irish outrage) to Dehn-Schmidt’s dismissal from the diplomatic service on the grounds that such behavior was unbecoming in a (Lutheran) representative of the Reich when relations with the Vatican were strained. It is believed that Mahr called the attention of the Nazi authorities to the photograph, although he later denied this. There can be little question that Mahr was zealous in his reportage, even to the extent that if Germany requested it, he could delve into the personal papers of families he suspected as having Jewish nomenclature and who could be of interest to Berlin.

From 1930 onward Mahr’s activities had become sufficiently noticeable, he fell under the close observation of the Irish police, Irish army intelligence, and the Department of External Affairs. By then the different security rungs of the state had informed themselves sufficiently that Mahr was a potential embarrassment to the new Irish Free State. The security services began to articulate concern of embarrassment to senior politicians if it became widely known. By the mid-1930s the tone of Mahr’s rhetoric even in his professional archaeology, suggested he believed a Nazi dictatorship was inevitable. Mahr added to the growing security neurosis of the Irish state by remarking on safeguarding museum collections in the event of war that, “if Ireland were occupied, it would be by a civilized nation which would respect these cultural treasures”. Only in July 1938 did he step down as leader of the Irish Nazi group on the grounds that it might cause conflict with his civil service position, though his resignation was not formally ratified by his German superiors until February 1939.

The paper trail is sparse, but Irish security officers played a significant role in persuading Mahr his “dual identity” had run its course and may have pressurized him to resign as Nazi organizer. Prior to the precipitation of this intervention from the Irish spooks, it is likely that Mahr had also over-played his cards. A letter to Mahr, dated 11 July 1939 and signed by an SS officer, suggests he may have deliberately abused his position in Ireland by supplying maps which could later have been used in the aborted Operation Green, a blueprint for an invasion of Ireland. His biographer, however, disputes this on the grounds that the quality of the information used in the blueprint is inferior to what Mahr could have supplied. We will never know just how helpful Mahr was to the Nazi machine, but it is apparent that we are dealing with an extraordinarily complex personality. On the one hand we see Mahr the Museums Service director and professional archaeologist, inspired by all things Celtic. Even into this we see the lacunae of politics, as he talks ad lib at a public meeting that Germany would respect Ireland’s national treasures. On the other hand, the resources which came to his hand, whether maps or personal data on suspects, were readily sent to Berlin, without a shadow of conscience. By this stage a schizophrenic monster had materialized: professional archaeologist by day, Nazi sleuth by night.

Exiled Never to Return

Events played a crucial part in determining Mahr’s war-time destiny, which also proved convenient for the Irish government and staved off diplomatic scandal. In July 1939 Mahr and his family left for Germany to visit relatives. The physical evidence shows that the family possessed tickets to return to Dublin after going to the famous Nuremberg rally of 2–11 September. The same evidence shows that Mahr tried to return to Dublin several times during the outbreak of war. Officially he had secured indefinite unpaid leave from the museum directorship and had not resigned. As far as the Irish state was concerned, his post was held open for him, leading to the conclusion that Dublin had retained in its employment a high-ranking Nazi throughout the war.

Unable to get back to Dublin, Mahr was given a slot in the German Foreign Office, pioneering radio propaganda directed against Ireland. His new broadcast medium was in the English language only, vehemently expressing German support for Irish neutrality, seeking to draw backing from the Irish diaspora and playing on religious sentiment as a good Catholic Austrian who understood the Irish Catholic hierarchy well. His voice, because of his strong Austrian accent, was rarely broadcast, but Mahr produced segments. He drew in a network of eccentric Irish émigrés and German scholars including Hilde Spickernagel. In 1944 Mahr became head of the Foreign Office section dealing with political broadcasting to the USA, Britain, Ireland – and later with a remit which included most of Europe. Significantly his talks show that he was fully aware of what was happening in the concentration camps of Europe.

Conclusions

At the termination of war, Mahr was detained by British occupation authorities in 1946 and ordered to undertake denazification. In summer 1945 he applied to return to Ireland (his two younger daughters, born in Ireland, were entitled to Irish nationality) and to resume his position as museums director. This was opposed by the Irish intelligence services, and there is an extant note from a senior deskman, Colonel Dan Bryan, who summarized Mahr’s record of Nazi activity. In the Dail, Deputy James Dillon took a personal interest in seeking Mahr’s ban from Ireland. There was a well-organized political and intelligence conspiracy to thwart any effort by remaining friends in the government to reappoint him.

Dail debates discussed activities incompatible with his civil service position. Government was also concerned about the implications for British attitudes towards Ireland in resuscitating the career of a notorious Nazi bureaucrat. As one state official said at the time, “he had no blood on his own shirt sleeve, but plenty near his hands”. Amazingly the Irish state did not simply banish him, and the records show that from 6 November 1948 he was pensioned off as keeper of Irish antiquities. Effectively erasing his record as museum supremo, the Irish state also pragmatically reduced his pension.

Mahr died full of political regret and begging the Irish authorities to accept him back. He had played curator and Nazi infiltrator with some level of success, and then also crystallized into the role of Nazi broadcaster. His last years were spent as a peripatetic lecturer on archaeological subjects, his original discipline. In 1948 he was appointed to lead a history institute in Bonn. He died from heart failure in 1951. The kindest thing one could say in his defence is that he did have a genuine passion for all things Celtic. A German nationalist who saw in Nazism a path to national greatness and an outlet for ordinary folk like himself to challenge the meritocracy. Although he was a bit player, it remains an embarrassing episode in Ireland’s museological history that it was directed by Ireland’s “Nazi No. 1.”

Sources

H. E. Kilbridge-Jones, ‘Adolf Mahr,’ Archaeology Ireland, vii (1993), 29–30

E. E. Evans, Ireland, and the Atlantic Heritage: Selected writings (1996), London, 216–17.

D. O’Donoghue, Hitler’s Irish voices (Dublin, 1998).

Maurice Manning, James Dillon (Dublin, 1999); and The Blueshirts, Gill Books, Dublin 2006,

John P. Duggan, Herr Hempel at the German legation in Dublin 1937–45 (Dublin, 2003).

Mervyn O’Driscoll, Ireland, Germany, and the Nazis: politics and diplomacy 1919–39 (Dublin, 2004).

Gerry Mullins, Dublin Nazi No. 1: The life of Adolf Mahr (Liberties Press, Dublin, 2007).

Michael Gibbons, Review, History Ireland, xv/5 (2007)

Mahr, Adolf, Entry Contributed by McGuinness, David; Maume, Patrick, originally published October 2009 as part of the Dictionary of Irish Biography, Last revised October 2009

Jacobsthal, Paul, “Celtic Art and the Nazis,” Oxford Archaeology Archives, Paul Jacobsthal | Archaeology Archives Oxford (WordPress.com)

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Fight Continues: New Access to Abortion Services in Ireland

- The Glasnevin Necrology Memorial: Exhibiting Ireland’s Dark Heritage

- Understanding Sinn Féin’s Abstention from the UK Parliament

- Opinion – Irish-American Diplomacy and the Catholic Orphanage Scandal

- Opinion – International Relations at the End of the Second Elizabethan Age

- The Dark Heritage of Holocaust Exterminators at Leisure