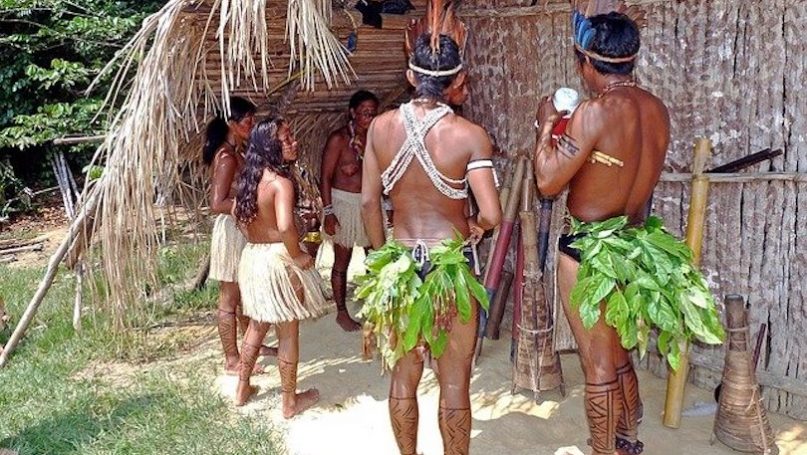

“Are you listening?”, she said. “The forest is talking to you.” This line, articulated by a Yanomami woman, is from the documentary The Last Forest (2021). Yanomami is an indigenous people living in a mountainous region of the Amazon forest, in today’s northern Brazil.[1] The director Bolognesi hopes that the documentary could introduce the audience to the life and resistance of the Yanomami, “from the interaction with them, from the desire of listening and understanding them in their own terms”.[2] It is a theatricalised representation of the Yanomami community. Yet through its artistic form, it also successfully impresses on the audience a deep sense of the uphill struggle for survival facing the indigenous peoples in Brazil.

Since the discovery of gold deposits in their land in 1986, the Yanomami have endured invasions by thousands of gold prospectors. Thousands of Yanomami people were murdered, not to mention the environmental pollution and diseases those prospectors brought.[3] They represent one of the many indigenous peoples—speaking various languages and imposed various names by Portuguese colonists[4]—who became known collectively as the “Indians”. For a contextualised understanding of the position of the indigenous in Brazil—or indeed the politics of indigeneity itself—we must go further back in history. The making of “the Indians” is inextricably intertwined with the making of “Brazil”, so much so that the anthropologist Gomes finds it “hard to associate the two in any other way than a zero sum”.[5] This essay attempts to trace the birth and shifting meanings of indigeneity in Brazil, from the start of Portuguese colonisation through Brazil’s independence to contemporary time. My contention is that the “indigenous” subjectivity was made and remade by the settlers for the elimination and discipline of human beings that have long resided on the land they occupied. I also discuss the implications this had for the peoples who have been considered indigenous, and how these dynamics have changed today.

The Newly “Indigenous” in Portuguese Brazil

The first encounter and the birth of the indigenous

What is meant by “indigeneity” or “the indigenous”? One would have answered differently had the history of the Lusophone South Atlantic not unfolded as it did. The position of the “indigenous”, it seems, could only make sense with reference to the process of contact and its enduring effects. Thus, I shall borrow the explication by Appiah and Robertson to orient this essay: Citing Appiah’s formulation that “few things . . . are less native than nativism in its current form”, Robertson contends that much of the notion of indigeneity today is “itself historically contingent upon encounters between one civilizational region and another”.[6] Just as Robertson uses the term “Glocalisation” to capture the dialectical relationship between the local and the global, we must also understand the indigeneity of the “Indians” in the context of Portuguese conquest of and encounter with peoples who had long resided in today’s Brazil. More important, this definition of indigeneity as an emergent product of contacts centres the modalities of co-existence and assimilation that were imposed on the Indians as a result of the colonial condition in Brazil since 1500. It is the vicissitudes of this condition that I shall trace.

Soon after Spain and Portugal signed the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, dividing the “New World” in halves, Portuguese sailors endorsed by the Crown began their attempts at navigating the Atlantic Ocean. As Cabral’s fleet finally found its way southwest to Brazil in 1500, the Portuguese also found there the “new species” that they called “the Indians”.[7]While no violent confrontation was recorded in official Brazilian history, hostility was already displayed upon the first encounter between the Portuguese and the native, as the colonisers raided native villages and the native fought valiantly back.[8] Still, it was not until 1534 that the Portuguese Crown divided Brazil into captaincies and granted local officials the power to enslave the Indians.[9] For Gomes, this was because of the 1529 bull Inter Arcana issued from Rome, which, following the “just war” philosophy, conveyed Catholic sanction for violent subjection of “the barbarian nations”, if necessary, to transmit “knowledge of God”.[10] To Schwarcz and Starling, this timing reflects Portuguese strategic calculation amid intensified competition among European powers for a share of the New World.[11]

In any case, from the native perspective, this saw the beginning of Portuguese invasion into their lands and exploitation of their labour. The Amazon itself was colonised in the 1620s, governed separately from other parts of Brazil.[12] One can argue this imperial encounter created the indigenous subject: All of a sudden, the sons of the soil became a “party” in this conflict for land ownership and free existence. (Indeed, this was the language used by the colonisers, calling the indigenous people nação gentílica [heathen nation] and themselves entradas/bandeiras [entry/slave parties].[13]) Clearly, the 1548 Regulations of Tomé de Souza had conditioned non-violent treatment of Indians on their accepting the colonial condition and gathering into aldeias for better “indoctrination” and availability of their labour power. Naturally, many Indians rejected Portuguese intrusion, which the colonisers took as a pretext for their enslavement. From 1548 to Brazil’s independence in 1822, dozens of ordinances were issued concerning the treatment of the Indians. Yet only in a few instances were there somewhat unambiguous declarations of “liberty of the Indians”, such as in 1570 with the Freedom of Indians Act,[14] and in the laws of 1605, 1609, and 1680.[15] (Even then, whether these were enforced is doubtful.) No matter how the language of these decrees changed, and regardless of the Crown and the religious orders’ shifting in and out of consensus, slavery or cativeiro remained a near constant reality for the conquered indigenous peoples.[16]

Logics of elimination and discipline

Apart from captivity and slavery—and to facilitate these acts—the indigenous peoples in some regions of Brazil had from early on been subject to a deliberate attempt at assimilation. Through the displacement and re-ordering of indigenous subjects, I argue, the colonisers aimed at the effects of discipline as well as elimination, in service of the imperial project.

What moves did the Portuguese colonists take specifically? There was firstly the task of moving the Indians living in the mountainous interior down to the east coast of Brazil near Portuguese settlements. This was partly so that the Indians could be integrated into the colonial economy, e.g., by working at engenhos (sugar-mills) near coastal settlements. But the relocation into aldeias also enabled the disciplining of Indians according to the colonisers’ administrative purposes and European notions of civilisation. Writing about late 18th century Porto Seguro, Barickman describes the Crown and local officials’ desire to “domesticate” the Indians, to acculturate them into a sedentary agrarian lifestyle. On the one hand, colonists like José Xavier Machado Monteiro had been abhorred by the perceived “vile, lazy, and corrupt” disposition of the native, who spoke “barbarous” languages, lived in communal huts, wore little clothing, and refused to produce marketable goods. Hence, particularly under Pombal’s policies, deliberate attempts were made to assimilate and “civilise” the Indians. This saw the creation of Directório dos índios (Directorate of Indians) in 1758, applied first in the northern and Amazonian captaincies of Para and Maranhao and later (after Brazil’s independence under Pedro II[17]) entire Brazil.[18] White “directors” were appointed to each aldeia to transform the “dense darknesses of [the Indians’] rustic ways”.[19] The institution of aldeias reminds of the panopticon: Indians were assigned fixed, nucleated residences for easy control; those residences, in turn, were to adhere to certain spatial orientations and locations (not to mention the presence of the church, town hall, and jail at the centre of vilas to symbolise the coloniser’s power). Native children were required to learn Portuguese and Catholic doctrines. And of course, the wearing of clothes outdoors was enforced; not borrowed clothes but bought, which contributed to the colonial economy, too.[20] By labouring and patrolling indigenous bodies, the colonists could render the Indians both subjected and productive (and the latter in both symbolic—affirming the colonisers’ supposed superiority—and material senses).[21]

Though the indigenous were thus intended to be useful, they were also subject to a logic of elimination, intensified by further Portuguese settlement over time (especially after Brazil’s independence). This might feel like a paradox or a flaw in the colonisers’ plan, as Barickman suggests.[22] Nevertheless, Wolfe’s explanation of “(structural) genocide” helps reconcile these seemingly contradictory logics. To Wolfe, the violence of settler colonialism is not equivalent to genocide as conventionally understood (actual killing of groups of human beings). It is rather the “grouphood”, or the “ongoingness” of an indigenous community’s mode of existence to borrow a communitarian expression from Walzer,[23]that settler colonialism sought to eliminate. This gives meaning to “genos” in this particular form of genocide.[24] By cultural assimilation, Portuguese colonisers disrupted (though not always successfully) the indigenous peoples’ ways of life. Their tremendously rich knowledges and practices, then unappreciated by Europeans, could have remained intact but instead suffered considerable losses. An epistemological/ontological violence no less eliminatory than direct coercion.[25]

The indigenous insubordination

The loophole in these strategies is that indigenous peoples were far from obedient. They resisted this colonial project in a multitude of ways, and indeed from the very beginning of their contact with the Portuguese, as mentioned. Barickman notes a lack of historical record on the specific modes of their resistance: We only know that marginalisation and exploitation notwithstanding, the Indians in Porto Seguro survived and continue to live. This, he argues, confirms speculations of Indians fleeing from supervised aldeias (such as the 1784 “sublevação da Ilha do Quiepe”, an uprising involving the flight of 900 Indians from several aldeias in the comarca of Ilheus, which lasted seven years[26]), and rumoured drunkenness in defiance to ban on alcohol production.[27] Still, some evidence is traceable. Established Portuguese settlements were sometimes raided by Indians. In the 1590s, for instance, the Indians attacked the settlement of Engenho Santana in Ilhéus, which by the 1570s had over a hundred slaves.[28] As Langfur notes, this was reflected in early cartographic references to Indians in the 17th century, showing that between the mouths of the Pardo and Paraiba Rivers, the much feared Botocudo whom colonisers called the Aimoré (literally the “evil ones”) had formed a barrier to Portuguese settlement, consequently limiting the wealth colonists could derive from Brazil.[29] Barickman puts the effect of Indian resistance in numbers: In Porto Seguro, these raids aroused so much fear and damage that the Portuguese population declined from 1,320 in 1570 to 600 in two decades, as two out of three captaincies were deserted, and only one of the seven engenhos there remained under control.[30]

The Indians who were resettled into aldeias also resisted through acts of insubordination to and contempt for colonial measures of discipline. Within their huts, native children above three years of age continued sleeping along with their parents, even though it was officially prohibited. There was no way to verify if Indians wore clothes indoors either. As for speaking Portuguese or native languages, Barickman notes that Indians simply took care not to speak their “barbarous tongues” in the presence of directors and other officials.[31] The descendants of some Indian peoples testify to Barickman’s account: Many Indian children the Portuguese set out to “civilise” had spoken their indigenous languages whenever possible, despite occasionally being caught and punished by the Portuguese.[32] Taken together, these acts of insubordination evince the limits of the colonisers’ authority, even though the indigenous peoples paid a tremendous price for their defiance and their cultures did not emerge unscathed.

Change and Continuity after 1822

From non-citizens to orphans and the landless dispossessed

With the independence of Brazil from Portugal in 1822, much of the dynamics between the colonisers and the indigenous peoples remained the same, following the logics of discipline and elimination. Initially, with a surge of a new desire for a Brazilian national identity, Brazilian elites debated the question of citizenship in the new empire, including the question of Indians. Early on, José Bonifácio de Andrade e Silva presented his “Notes on the Civilisation of the Barbarian Indians of Brazil” to the Constituent Assembly in 1823 for consideration of the Indians’ place in the new nation.[33] Yet this was not taken up, as the new king Pedro I of Brazil, son of king John VI of Portugal, sanctioned a Constitution without any mention of the Indians.[34] Miki explained this in terms of the new government’s inability to confront the legal questions posed by such a heterogeneous population as Brazil’s. Such attempts notwithstanding, Indians in Brazil were left in the same predicament as slaves, and many remained poor and exploited. Major rebellions erupted in early 19th century. In the early 1830s, Indians along with runaway slaves in Pernambuco and Alagoas fought a three-year rebellion against provincial authorities and sugar planters to protect their land.”[35] Another revolt in 1832, the Guerra dos Cabanos, was staged by run-away slaves and free Indians.[36] As Barman writes, this was unsurprising, given that the new Imperial regime, the land-owners, and the merchants colluded in the continued exploitation of slaves and the poor free Indians.

Only under Pedro II were new attempts made at legislation of Indian incorporation.[37] Ironically, this proved merely another stage of exploitation and elimination of the Indians. Under pressure to abolish slavery, the settlers already began expanding their territory to indigenous lands and relied increasingly on enslavement of Indians. When in 1831, Indians were classified as “orphans”.[38] Under state “guardianship”, they were to be educated, through labour (or slavery with a meagre pay). Alongside continued forced labour was an “emancipatory” effort. A Regiment of the Missions was created in 1845, guided by the motto catquese e civilização (Christianisation and civilisation) pursued by the directorate and Capuchin missionaries.[39] The same assimilatory/eliminatory desire shines through these apparent changes.

Importantly, anticipating the contest for land ownership today, the Law of the Lands was issued in 1850, with major consequences for the indigenous peoples. It established that every property claim must be registered and legalised in public land registrar offices. This excluded most Indians from claiming legal ownership of land, given their lack of access to lawyers and capacity to navigate the bureaucratic processes.[40] Later political officials nullified much of the Indians’ lands and made them public, “through contrived legal means as well as by sheer political power”. [41] Deprivation of homeland, along with increased contact with autonomous indigenous peoples which brought them fatal diseases, caused the population of many communities to decline from millions to tens of thousands by the 19th century. As if to find some comfort in this reality, 19th century Brazilian elites embraced Social Darwinism and promulgated the idea that the indigenous, or “maladaptive”, were doomed for extinction.[42] Such is the brutality of colonialism for the indigenous peoples: the more valuable their ancestral lands, the more expendable the peoples themselves became to the settlers. As Wolfe writes, citing Rose, “where they are is who they are, and not only by their own reckoning. . . . [T]o get in the way of settler colonization, all the native has to do is stay at home.”[43] The “indigenous”, in such a context, was made by the settlers for disappearance.

Institutional approaches to the Indian question and competing interests in Republican Brazil

After centuries of struggles by indigenous peoples themselves, the protection of indigenous rights was finally institutionalised with the formation of the Indian Protection Service (SPI) and later the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI). What motivated SPI’s creation in 1910 was growing sympathy among educated Brazilians in major cities.[44]The result of this development was mixed. SPI recognised Indians as “people in isolation” rather than “savage”, and offered some basic protection from potential invaders. By the 1950s, over a hundred service posts had been set up on (non-autonomous) Indian lands. It promoted indigenous culture in collaboration with museums and UNESCO. Despite all this, SPI failed to stop the decline in indigenous population, which fell to a historic low of 100,000 at one time.[45] Faced with industrial advances into indigenous lands, SPI could only act as “pacifier” of the Indians, negotiating (as if it were negotiable) with them for a division and distribution of the land concerned.[46]

The FUNAI, on the other hand, was a product of the 1964 coup d’état and the installation of the military regime. The then declining SPI was to the distaste of the regime and was abolished. Instead, it tasked the new FUNAI with resolving the “Indian question”. This turned out to mean accelerated assimilation of Indians into Brazil. FUNAI helped demarcation of indigenous lands and enjoyed periods of friendly relationship with Indians. But mostly, following the “military regime’s doctrine of “economic development with national security”, it simply intensified contact with autonomous Indians, and “managed” them more efficiently without compromising other parties’ (often anti-Indian) interests.[47] Companies turned to FUNAI, too, to carry out (illegal) mining.[48] In its nationalisation project—to make the indigenous a content member of modern Brazil—FUNAI’s success (to achieve its goals) was fairly limited, which is in any case better for the indigenous, as Gomes contends.[49]

Whether one views these institutional approaches as paternalistic but pathetic attempts at protection (despite that 1988 Constitution implied the end of Indians’ state wardship[50]), or as insidious acts of assimilation, we must note how much remained unchanged through the vast span of history during which “indigeneity” has emerged and been transformed multiple times. Even under the façade of harmony painted by Gilberto Freyre’s idea of “Luso-tropicalism” and “racial democracy”, still influential among political elites, one senses the inherent inequality in the colonial and later nation-building project.[51] As Quijano and Ennis argue, the making of the modern Brazilian nation-state “a la europea” is itself a process of homogenisation that has made the indigenous subject an enemy.[52] It is no wonder, then, that despite institutional efforts and growing international attention, modern Brazil remains hostile to indigenous existence. For such is the meaning of “indigeneity” as inscribed by, to quote Quijano, a “coloniality of power”.

Remaking the Indigenous Subject

The Lusophone world, in indigenous terms

“The non-native authorities use this word a lot: ‘important’. For you, who live in the city, products are the most important thing… What matters to us are the animals in the forest, fertility… our survival, our growth, our way of life, and our existence as people.”[53] These are the words of Davis Kopenawa, shaman and representative of the Yanomami people and one of the screenwriters for The Last Forest, at Harvard University, addressed to a mostly white audience. Such sights have become more common in recent years as indigenous people become increasingly vocal (or increasingly heard) in advocating for their rights against infringement by the state and industries. Not only have many indigenous peoples experienced a “demographic turnaround”, they have also found a new language for their struggle in light of the changing worldview of the international community.[54] Climate change in indigenous lands and worldwide highlights the importance of protecting both the forests and their residents. Thus, in their advocacy, organisations like the UN, Survival International, and indigenous peoples themselves have linked the twin causes of environmental protection and indigenous survival.[55] Postcolonial thinkers are also standing in solidarity with the indigenous subalterns, as they shed light on insights from indigenous cosmologies.[56] These have offered a new language[57] and a new realm of speech for those relegated to the margins of the modern age.

Still, in the final analysis, there is something disturbing in the language that the indigenous are the best guardian of the forest,[58] and “helpful” for alleviating the unfolding climate crisis. Doubtless, there is much to learn from indigenous peoples in Brazil and elsewhere to inspire alternative imaginaries of the Anthropocene.[59] Yet at its heart, this utilitarian language echoes the logic of elimination central to settler colonialism. It is precisely as a result of this logic of settler colonialism, as elaborated by Wolfe, that indigenous peoples in Brazil, despite surviving the colonial condition, have largely saw their native title/entitlement extinguished. The wound goes still deeper. As Brantlinger argues, “the juggernaut of economic development [is] to peoples trying to maintain traditional ways of life . . . just as destructive as armed massacres.”[60] To bring the modern Brazilian nation-state “to the right court”, the genocidality of the modern condition must be the focus, not some fading hope for potential benefits from the indigenous peoples’ survival; the Anthropocene is not their responsibility. Massacre is still ongoing (not to forget how COVID-19 affects indigenous peoples), as gold prospectors raided indigenous lands and polluted rivers with mercury.[61] While indigenous peoples continue to press for their demands,[62] the Bolsonaro regime has resolutely rejected their claims to ancestral lands.[63]

To conclude, the shifting constitution of “indigeneity” in Brazil charts a history of the indigenous peoples’ resistance against colonial closure of the frontier. Thus far, coloniality (even in postcolonial times) appears triumphant. Whether this sounds pessimistic, the language of modernity reigns supreme. Yet, lest we forget, the indigenous peoples’ reality remains one of refusing to be mourned as “(near-)extinct”, refusing to be written out of history along with their struggles for a rightful place in Brazil, and refusing to relinquish to an intrusive colonio-capitalist ideology. Therein lies the incivility of and crucial challenge to the modern capitalist world and modern Brazilian regime, which the making of indigeneity for elimination constantly reminds one of.

Notes

[1]In this essay, I use the terms “indigenous”, “Indian”, and “native” interchangeably. As my theoretical framework will make clear, I would treat none of these terms as more detached from colonial influence than the others.

[2] Bolognesi, The Last Forest.

[3] Gomes, The Indians and Brazil, 5.

[4] Gomes provides a detailed outline of the different indigenous “ethnies” with their corresponding language families and geographical regions. Nonetheless, such anthropological categorisations are certainly to some extent arbitrary, as Gomes admits when discussing conflicting figures in existing literature. See ibid., 132–53, 250–58, and 259, footnote 2.

[5] Ibid., 1.

[6] Appiah, In My Father’s House, 60; quoted and elaborated in Robertson, “Glocalization,” 37–38.

[7] Schwarcz and Starling, “First Came the Name, and Then the Land Called Brazil.”

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Quoted in Gomes, The Indians and Brazil, 58.

[11] Schwarcz and Starling, “First Came the Name, and Then the Land Called Brazil.”

[12] Gomes, The Indians and Brazil, 67.

[13] Ibid., 59–60.

[14] Schwarcz and Starling, “First Came the Name, and Then the Land Called Brazil.”

[15] Gomes, The Indians and Brazil, 64.

[16] Ibid., 59–64.

[17] Ibid., 72.

[18] Barickman, “‘Tame Indians,’ ‘Wild Heathens,’ and Settlers in Southern Bahia,” 337.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid., 338–41.

[21] Foucault, “Panopticism”; and Foucault, “The Body of the Condemned.”

[22] Barickman, “‘Tame Indians,’ ‘Wild Heathens,’ and Settlers in Southern Bahia.”

[23] Walzer, “Emergency Ethics,” 43.

[24] Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” 398.

[25] Ibid., 401.

[26] Barickman, “‘Tame Indians,’ ‘Wild Heathens,’ and Settlers in Southern Bahia,” 351, note 76.

[27] Ibid., 351.

[28] Schwartz, Slaves, Peasants, and Rebels, 51.

[29] Langfur, The Forbidden Lands, 39.

[30] Barickman, “‘Tame Indians,’ ‘Wild Heathens,’ and Settlers in Southern Bahia,” 330.

[31] Ibid., 341; Carelli et al., Indians in Brazil.

[32] Carelli et al., Indians in Brazil.

[33] Gomes, The Indians and Brazil, 9.

[34] Ibid., 70; Miki, “Outside of Society,” 2018, 34.

[35] Barickman, “‘Tame Indians,’ ‘Wild Heathens,’ and Settlers in Southern Bahia,” 326.

[36] Barman, Brazil, 169.

[37] Miki, “Outside of Society,” 2018, 34.

[38] Ibid., 53.

[39] Gomes, The Indians and Brazil, 72; Miki, “Outside of Society,” 2018, 34.

[40] Gomes, The Indians and Brazil, 72–73.

[41] Ibid., 73.

[42] Ibid., 74; Miki, “Outside of Society,” 2018, 102–4.

[43] Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” 388.

[44] Gomes, The Indians and Brazil, 77.

[45] Ibid., 77–81.

[46] Ibid., 81.

[47] Ibid., 82–88.

[48] Ibid., 177.

[49] Ibid., 83.

[50] Miki, Frontiers of Citizenship, 259.

[51] Dávila, “Brazil in the Lusotropical World.”

[52] Quijano and Ennis, “Coloniality of Power.”

[53] Bolognesi, The Last Forest.

[54] Gomes, The Indians and Brazil, ix–xii.

[55] For example, see FAO and FILAC, Forest Governance by Indigenous and Tribal Peoples; and Survival International, The Big Green Lie.

[56] For instance, Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire.

[57] It is certainly true that this language (of indigenous survival being inextricable from the many “global challenges” of the modern world) is not entirely new, nor does it belong only if at all to the indigenous. In some sense, it could even be interpreted into a binary of indigenous (nature)/settler (culture). As I have tried to maintain throughout this essay, much of the articulations by the indigenous and the non-indigenous have as the referent the other party of this dialectical pair. Hence my qualification next about the colonial imprint on this language. Still, I think one cannot deny indigenous agency. The key is to recognise that “agency” makes no sense outside a system of oppression, which can be so crushing that a broad-based and strategic alliance for resistance is urgently needed.

[58] Carrington, “Indigenous Peoples by Far the Best Guardians of Forests – UN Report.”

[59] See, for instance, Pereira and Gebara, “Where the Material and the Symbolic Intertwine.”

[60] Brantlinger, “White Twilights,” 190.

[61] Bolognesi, The Last Forest; “Report.”

[62] “Thousands of Indigenous People in Brasilia Press for Their Ancestral Right to Land.”

[63] “Bolsonaro Reiterates That Further Demand for Indigenous Lands Threatens Brazilian Agriculture”; “Brazil Government Authorizes Armed Forces Deployment on Indigenous Lands in Rio Grande Do Sul State.”

Bibliography

Appiah, Kwame Anthony. In My Father’s House: Africa in the Philosophy of Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Barickman, B. J. “‘Tame Indians,’ ‘Wild Heathens,’ and Settlers in Southern Bahia in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries.” The Americas 51, no. 3 (January 1995): 325–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/1008226.

Barman, Roderick J. Brazil: The Forging of a Nation, 1798-1852. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1988.

Bolognesi, Luiz. The Last Forest [A Última Floresta]. 2D, Documentary, Drama. Gullane and Buriti Filmes, 2021. Accessed 28 March 2022. https://www.aultimafloresta.com.br/en/.

“Bolsonaro Reiterates That Further Demand for Indigenous Lands Threatens Brazilian Agriculture.” The Rio Times, September 15, 2021. Accessed 1 April 2022. https://www.riotimesonline.com/brazil-news/brazil/bolsonaro-reiterates-that-the-demand-for-indigenous-lands-threatens-the-brazilian-countryside/.

Brantlinger, Patrick. “Conclusion: White Twilights.” In Dark Vanishings: Discourse on the Extinction of Primitive Races, 1800-1930, 189–99. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2003. https://doi.org/10.7591/j.ctt1287f39.

“Brazil Government Authorizes Armed Forces Deployment on Indigenous Lands in Rio Grande Do Sul State.” The Rio Times, October 19, 2021. Accessed 1 April 2022. https://www.riotimesonline.com/brazil-news/brazil/brazilian-government-authorizes-deployment-of-national-armed-forces-on-indigenous-lands-in-rio-grande-do-sul-state/.

Carelli, Vincent, Bras de Oliveira Franca, Pedro Garcia, Azilene Inácio, Quitéria Maria de Jesus, Bonifácio José, Agenor Gomes Juliao, and Joaquim Paula Mana. Indians in Brazil: Our Languages. Video in the Villages. Watertown (Mass.): Documentary Educational Resources DER, 2000. Accessed 28 March 2022. http://www.aspresolver.com/aspresolver.asp?ANTH;765046.

Carrington, Damian. “Indigenous Peoples by Far the Best Guardians of Forests – UN Report.” The Guardian, March 25, 2021, sec. Environment. Accessed 1 April 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/mar/25/indigenous-peoples-by-far-the-best-guardians-of-forests-un-report.

Dávila, Jerry. “Brazil in the Lusotropical World.” In Hotel Trópico: Brazil and the Challenge of African Decolonization, 1950–1980, 11–38. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010. Accessed 7 March 2022.

FAO and FILAC. Forest Governance by Indigenous and Tribal Peoples: An Opportunity for Climate Action in Latin America and the Caribbean. Santiago: Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), 2021. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb2953en.

Foucault, Michel. “Panopticism.” In Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, translated by Alan Sheridan, 2nd ed., 195–228. New York: Vintage Books, 1995.

———. “The Body of the Condemned.” In Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, translated by Alan Sheridan, 2nd ed., 3–31. New York: Vintage Books, 1995.

Gomes, Mercio. The Indians and Brazil. 3rd ed. Gainesville, Fla., [etc.]: University Press of Florida, 2000.

Langfur, Hal. The Forbidden Lands: Colonial Identity, Frontier Violence, and the Persistence of Brazil’s Eastern Indians, 1750-1830. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006. Accessed 29 March 2022.

Miki, Yuko. Frontiers of Citizenship: A Black and Indigenous History of Postcolonial Brazil. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108277778.005.

———. “Mestiço Nation: Indians, Race, and National Identity.” In Frontiers of Citizenship: A Black and Indigenous History of Postcolonial Brazil, 100–134. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108277778.003.

———. “Outside of Society: Slavery and Citizenship.” In Frontiers of Citizenship: A Black and Indigenous History of Postcolonial Brazil, 28–62. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108277778.003.

Pereira, Joana Castro, and Maria Fernanda Gebara. “Where the Material and the Symbolic Intertwine: Making Sense of the Amazon in the Anthropocene.” Review of International Studies, March 8, 2022, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210522000134.

Quijano, Aníbal, and Michael Ennis. “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America.” Nepantla: Views from South 1, no. 3 (2000): 533–80. Accessed 9 August 2021. http://muse.jhu.edu/article/23906.

“Report: Brazil’s Isolated Indigenous Territories Lost 3,200 Hectares to Deforestation in 2021.” The Rio Times, January 31, 2022. Accessed 1 April 2022. https://www.riotimesonline.com/brazil-news/rio-politics/report-brazils-isolated-indigenous-territories-lost-3200-hectares-to-deforestation-in-2021/.

Robertson, Roland. “Glocalization: Time-Space and Homogeneity-Heterogeneity.” In Global Modernities, edited by Mike Featherstone, Scott Lash, and Roland Robertson, 25–44. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: SAGE Publications, 1995.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2018.

Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz, and Heloisa Maria Murgel Starling. “First Came the Name, and Then the Land Called Brazil.” In Brazil: A Biography, E-book Ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017. Accessed 5 February 2022.

Schwartz, Stuart B. Slaves, Peasants, and Rebels: Reconsidering Brazilian Slavery. Blacks in the New World 842476822. Urbana [etc.]: University of Illinois Press, 1992.

Survival International. The Big Green Lie, 2021. Accessed 1 April 2022. https://www.survivalinternational.org/campaigns/biggreenlie.

“Thousands of Indigenous People in Brasilia Press for Their Ancestral Right to Land.” The Rio Times, August 25, 2021. Accessed 1 April 2022. https://www.riotimesonline.com/brazil-news/brazil/thousands-of-indigenous-people-press-for-their-ancestral-right-to-land-in-brasilia/.

Walzer, Michael. “Emergency Ethics.” In Arguing About War, 33–50. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

Wolfe, Patrick. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (December 1, 2006): 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Settler-Colonial Continuity and the Ongoing Suffering of Indigenous Australians

- Constraints On Rape As a Weapon of War: A Feminist and Post-Colonial Revision

- Frantz Fanon and the Inefficacy of Anti-colonial Violence

- Populism and Extractivism in Mexico and Brazil: Progress or Power Consolidation?

- Decolonising World Politics: Anti-Colonial Movements Beyond the Nation-State

- Terrorism as Controversy: The Shifting Definition of Terrorism in State Politics