The concept of danger has been critical to establishing the nation-state and its sovereignty (Dillion, 1996). The mainstream security scholarship believes that danger can be overcome through rational choice (Keohane, 1989). This dissertation investigates how states can both overcome and construct danger logically and purposefully. The practices of danger are not only relevant to this dissertation but also to international security politics. Indeed, the discourse of danger has become the foundation of political authority and order to the point where the discursive construction of the state originates from the discursive construction of danger (Dillon, 1996). Even though the latter is not a fixed, objective condition (Campbell, 1998: 2), states extensively use it to reconfigure their identity (Doty, 1996).

This dissertation is set out to answer the question “Do the failed states breed narco-terrorism?”. By answering the research question, this study will meet three aims. It will establish the causational relation, or the lack thereof, between failed states and narco-terrorism; it will re-frame narco-terrorism’s ontology, and it will re-frame narco-terrorism’s epistemology.

The Relevance of the Study: Research Question and Aims

The broader consensus among scholars presents narco-terrorism as a phenomenon facilitated by failed states. Makarenko (2004a) introduced “black holes” as the epitome of the danger posed by hybrid groups. Lamb (2008) extensively evaluated how failed states become safe havens for illicit actors, and Rotberg (2002a) emphasised the significance of safe havens’ repercussions on the international system, highlighting how they can become a source of significant instability and a danger to “functioning states”. It follows that the existent academic literature links the two phenomena through a causational relation. However, the literature fails to explore what led to the conclusion that failed states breed narco-terrorism and fails to explain how the latter phenomenon has made its way on the global security agenda.

This dissertation contributes to the existent literature because it adds a level of analysis that had not been considered before by answering the research question. The current study has gathered the fundamental theories and arguments around narco-terrorism and failed states. It has compared them with the empirical evidence drawn from Afghanistan and Colombia to demonstrate that narco-terrorism is a fabrication and claiming that “failed states” breed the latter is ontologically inaccurate.

Structure

The first chapter of this dissertation is the methodology, which will look at the ontological and epistemological positions that have informed this study, the motivations for conducting a qualitative secondary data analysis, and the choice of case studies as a method of analysis. The following chapter is a literature review, highlighting the leading academic positions and theoretical frameworks on the concepts of narco-terrorism and failed states. The next section, “Case Studies”, features an in-depth analysis of The War on Terror (Afghanistan) and Plan Colombia (Colombia). This chapter is critical to contextualise the notions presented in the literature review and evaluate their relevance. In conclusion, the discussion will draw upon the literature review and the case studies to answer the research question and re-define narco-terrorism’s ontology and epistemology by applying Constructivism and OST in International Security Studies.

Methodology

This is a qualitative study that engages secondary data (predominantly written materials). Qualitative research focuses on understanding the meanings and dimensions of humans’ lives and social worlds (Fossey et al., 2002: 717). Secondary data analysis refers to the use of data produced by other studies (Hammond and Wellington, 2020: 166). Secondary research is often criticised for giving researchers too much room to interpret and use someone else’s findings (Heaton, 2008: 40) that might not even fit the purpose of the current research (Walliman, 2017: 86). Nonetheless, in line with the Critical Research paradigm, which implies a Constructivist worldview that assumes that reality is socially constructed through historical and cultural norms (Cresswell, 2007: 20-21), this research seeks to challenge the power structures as society knows them. Thus, the issue of interpretation is not valid because the current dissertation is built upon the notion that the world is shaped by different understandings of the same structures and phenomena. More specifically, this dissertation required secondary analysis because it allowed the re-interpretation and new questioning of the data, which warranted the emergence of new themes and perspectives (Corti et al., 2006: 7). Indeed, this dissertation begins by looking at narco-terrorism in the context of failed states and ends by re-shaping narco-terrorism ontology and epistemology.

According to Hox and Boeije (2005), secondary researchers face three key challenges: locating valuable data sources, retrieving relevant data, and evaluating whether the data meets the purpose of this research. The data for this dissertation has been collected from the Internet. The web search engine Google Scholar and the BCU online library service have been the two primary sources to locate academic material. The keywords used for the literature review are: narco-terrorism, failed states, black holes, international relations, narco-terrorism black holes, and crime-terror nexus. The keywords used for the case studies are war on terror, US intervention Afghanistan, Plan Colombia, and Colombia narco-terrorism. Retrieving the data was not a challenge, as all material used was easily accessed through the researcher’s academic account. The task of identifying how relevant a potential source could be was accomplished differently according to the dissertation section. Such a process proved to be easier for the literature review, as almost every academic source available on the Internet contained relevant information on both narco-terrorism and failed states. However, sources that provided an overall take on the two phenomena were preferred over sources that focused on a specific instance of narco-terrorism or a failed state. For the case studies, the bibliographies within the academic sources were crucial in navigating the literature and understanding which author would have been more helpful in investigating a particular aspect of the case study.

Why Case Studies?

Given that Security is a speech act (Austin, 1962: 6), this study could have used a Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), the purpose of which is to analyse “opaque as well as transparent structural relationships of dominance, discrimination, power and control as manifested in language” (Wodak, 1995: 204). Although CDA focuses on relations of power and dominance in the social and political context, to meet this dissertation’s aims, the analysis had to consider various levels beyond the discursive one. CDA would have limited the analysis to the discursive realm, and thus overlooked what was done because of what had been said. By using case studies, this limitation was overcome.

A case study is an empirical enquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon in context when the boundaries between the phenomenon and the context are not evident (Yin, 1994). The case study approach is the best approach for this research because it allows for the investigation of narco-terrorism in the context of failed states, starting from the notion that failed states breed narco-terrorism. Case studies are versatile options for small-scale research (Rowley, 2002) that seek to shed light on how relationships and processes are interconnected (Denscombe, 2014: 53) and to understand how something “got the way it is” (Van Wynsberghe and Khan, 2007: 90). Thus, using case studies has allowed this dissertation to unpack the narco-terrorist phenomenon in a “natural setting” (failed states) and generate theories that look at the particular to explain the general. This dissertation has picked Afghanistan and Colombia as case studies because they fulfil Denscombe’s typical instance criterion (2014: 56), meaning that narco-terrorism is present in both states, which are either failed or failing.

The scathing criticism against case studies targets their extent of generalisability and the overall validity of the findings (Denscombe, 2014; Burton, 2000). The generalisation process is analytical for what concerns the current study (Rowley, 2002: 20). Therefore, the literature review serves as a theoretical template to compare the empirical results drawn from Afghanistan and Colombia. How generalisable is what will be read in the findings is an unclear question. If the expectation is to achieve a quantitative-like generalisability, then the current findings are not generalisable because this is a qualitative study underpinned by constructivism. Nonetheless, this dissertation aims not to generate a theory that is always applicable or to produce results that are always representative. This dissertation has produced findings that will hopefully help unpack how power dynamics work under a specific set of circumstances and conditions. These mechanisms are generalisable because they might be applied to different contexts that follow similar rules, bearing in mind that reality is constructed, interpreted, and multifaceted. Indeed, it could be argued that had this dissertation used Somalia and France as opposed to Afghanistan/Colombia and the US, the results would have been different. Undoubtedly. Somalia does not have the same value to France as Afghanistan/Colombia to the US, and France is not the US. Consequently, the lessons learnt from The War on Terror and Plan Colombia have limited generalisability in the bigger picture. Nonetheless, the ontology and epistemology of how those military interventions came about have certainly produced relevant insights into understanding the overall dynamics at play in the international system.

Ethical Issues

In terms of ethical implications, when it comes to secondary data analysis, significant concerns emerge around potential harm to individual subjects and the issue of return for consent (Tripathy, 2013: 1478). However, this dissertation uses data that does not contain quantitative results or personal or sensitive information. Moreover, the data used is freely available on the Internet; hence, permission for further use is implied (Tripathy, 2013) Because the use of secondary is an intrinsically ethical practice, and, as such, it is only valid when its benefits outweigh the risks (Tubaro, 2015), the current research meets the fundamental ethical condition (Tubaro, 2015) of not causing any damage or distress with its results.

Literature Review

This chapter will explore the concepts of narco-terrorism and failed states. In doing so, it will be divided into two sections. The first one will look at definitional issues and official definitions of narco-terrorism. Subsequently, it will explore scholars’ theories regarding functional interactions between criminals and terrorists and their meanings to the international community. Conclusively, the last part will look at how policy has been re-shaped around narco-terrorism and its implications.

The second section of this literature review will define failed states and explain why they are considered a security threat. Afterward, it will look at criticism and alternatives to this concept. Finally, it will explore the ideal policy approaches to failed states.

Narco-Terrorism

Definitional Issues

Although narco-terrorism originally referred to the way Latin American drug lords and criminal organisations influenced local governments (CSIS, 1991: 1), it soon became a phenomenon of global scope and reach (Wardlaw, 1988: 6). The Australian criminologist Grant Wardlaw was the first to highlight the potential shortcomings of this rapidly spreading concept. He suggested that narco-terrorism is often misconstrued to imply a conspiracy that merges criminal and political goals into a new kind of threat, which warrants unrealistic expectations and responses (Wardlaw, 1988). Approximately three decades later, Pellerin (2014) proposed a similar interpretation of narco-terrorism as a dangerous umbrella term that could hinder understanding of how criminals and terrorists practically interact.

Although scholars have already questioned the legitimacy of narco-terrorism, the relevant literature has yet to unpack the ontology of narco-terrorism, namely how it has come into existence. Wardlaw defines it as “a potent weapon in the propaganda” and a “catchword” (Wardlaw, 1988: 5-6); Pellerin calls it an “umbrella term” (2014: 25). However, neither explores how such a dangerous concept has been introduced into mainstream security discourse.

Official Definitions

The Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) defines narco-terrorism as a “subset of terrorism, in which terrorist groups, or associated individuals, participate directly or indirectly in the cultivation, manufacture, transportation, or distribution of controlled substances and the monies derived from these activities. Further, narco-terrorism may be characterised by the participation of groups or associated individuals in taxing, providing security for, or otherwise aiding or abetting drug trafficking endeavours to further, or fund, terrorist activities” (Hutchinson, 2002: 13). Conversely, the Department of Defence (DOD) understands the same phenomenon as “[t]errorism conducted to further the aims of drug traffickers. It may include assassinations, extortion, hijackings, bombings and kidnappings directed against judges, prosecutors, elected officials, or law enforcement agents, and general disruption of a legitimate government to divert attention from drug operations” (Thachuk, 2007: 24).

These definitions demonstrate two different understandings of the same concept. The DEA explains narco-terrorism as a means for terrorists to gain revenue; whereas, the DOD understands the latter as a diversion used by criminals to keep law enforcement agencies busy.

Narco-terrorism combines organised crime and terrorism. Organised crime is “the illicit movement of prohibited drugs across international borders by individuals, groups or states for financial gain and/or political purpose” (Warner, 1984: 44). Conversely, terrorism has no universally recognised definition (Wardlaw, 1982) and suffers from definitional stretching (Weinberg et al., 2004: 779; Bjornehed, 2004: 307).

As its name suggests, narco-terrorism is a ramification of terrorism. How can narco-terrorism be defined if terrorism still lacks a universal definition? Moreover, because narco-terrorism is a global phenomenon (Wardlaw, 1988: 6), the fact that the DEA and the DOD have such competing takes on the same phenomenon is contentious because it implies that the two agencies will have completely different approaches to countering the same threat. The policy section will elaborate on how this might be detrimental.

The Crime-Terror Nexus

Overall, scholars agree that there is insufficient evidence to fully understand the relationship between terrorists and criminals (Makarenko, 2004a; Bjornehed, 2004: 308; Schmid, 2005; Wardlaw, 1998: 11; Mullins and Wither, 2016: 65; Reitano et al., 2017). Therefore, Reitano and colleagues (2017) advise against using the word “nexus”, as it would erroneously imply a global trend, generalisable and applicable everywhere. Yet relationships between criminals and terrorists are not straightforward and not the same everywhere (Reitano et al., 2017); hence, every “link” should be considered independently. Notwithstanding Reitano and colleagues’ position, the expressions “crime-terror nexus” and “narco-terrorism” are used interchangeably in the literature, even though there is no agreed-upon definition for either of the two. This dissertation will conclude that these two expressions should not be classed as synonyms.

Ehrenfeld and Kahan (1986) used the Guillot-Lara episode to explain the link between terrorists and narco-traffickers as an attempt to undermine the West by the Soviet Union and its allies. Although the example lends itself quite well to supporting Ehrenfeld and Kahan’s thesis, Miller and Damask (1996: 115) argued that it transformed an ephemeral association of convenience into an ideological relationship that does not exist. Although the “Communist” thesis was flawed, it shows what Wardlaw meant by narco-terrorism as a “propaganda tool” (1988: 6). Indeed, Ehrenfeld and Kahan’s theory exemplifies the US’s readiness to fall back into Cold War-like narratives. This dissertation will identify a similar pattern that led the US to conceive narco-terrorism.

According to the dominant academic position, criminals and terrorists develop short-lived, instrumental relations that last only as far as both groups benefit from them, or until one of the parties develops in-house capabilities (Schmid, 2005; Dishman, 2001; Bjornehed, 2004; Mullins and Wither, 2016; Reitano et al., 2017). Fleeting associations are due to significantly different motivations. Specifically, terrorists tend to have political or ideological motivations that inevitably challenge the status quo, while criminals seek profit and material gains (Bjornehed, 2004: 312; Makarenko, 2004b: 7; Schmid, 2005: 6; Reitano et al., 2017). It follows that with such inherently different objectives, no cooperation within the crime-terror nexus harbours the potential to develop into a global conspiracy. However, it was noticed that terrorists and criminal groups tend to look increasingly alike because they learn and borrow tactics from each other. Indeed, Bjornehed (2004: 304-309), Schmid (2005), and Anderson (2004) all explained that both groups share a similar internal hierarchy, operate from the same murky parts of society through kidnappings, killings, intimidation and extortion, and tap into the same resources (fake passports, weapons, money laundering).

Conversely, other scholars describe a real communion of intent between the groups. Makarenko (2004a) argues that some relationships may give birth to hybrid groups whose objectives can no longer be defined as purely political or profit-oriented. Such a convergence of motives is problematic when a hybrid group successfully takes over a state that lacks the political structure to survive, turning it into a black hole (Makarenko, 2004a). Comparably, Curtis and Karacan (2002), Williams (2014), and Mullins and Wither (2016) indicate the possibility of different levels of interactions between the groups.

Again, it is taken for granted that, in some cases, illicit actors might cooperate in some way. Nonetheless, there is still no research on specific examples of a nexus and thorough investigations of the circumstances that led to the formation of said nexus and how it was dealt with. This dissertation will bridge this gap by looking at specific instances of narco-terrorism in Afghanistan and Colombia.

Policy

In the aftermath of 9/11, the policy division between terrorism and organised crime began to fade (Bjornehed, 2004: 141). Since the two phenomena became interlinked in practice, their policies could no longer be separate (OSCE, 2002). However, no justification is provided as to why 9/11 has led to such consequences. This dissertation will examine the role of 9/11 in influencing policies and agendas.

The idea of merging policies draws upon the notion that terrorists and criminals use similar tactics (Bjornehed, 2004), hence what works against one group must work against the other, and the notion that the criminal underworld generates terrorists’ profit (UNSC, 2001). However, scholars posit that merging policies against terrorists and criminals is detrimental and inefficient (Bjornehed, 2004; Miller and Damask, 1998; Pellerin, 2014; Shaw and Mahadevan, 2018). This notion alone is enough to question the existence of narco-terrorism.

Pellerin advises against militarised responses as they tend to reinforce the narco-terrorist connection (2014: 30). This dissertation will explore the “collateral damage” of said militarised responses to narco-terrorism and why they have been preferred over softer means. Regardless of their tactical similarities, crime and terrorism require different counterstrategies, hence narco-terrorism might mislead policy (Pellerin, 2014: 29; Miller and Damask, 1996: 121).

Sometimes policy tends to overemphasise only one end of the nexus (Reitano et al., 2018). The DEA and DOD’s respective definitions of narco-terrorism are proof of this. Consequently, competition between agencies (Mullins and Wither, 2016: 78) and reluctance to share classified information (Pfneisl et al., 2013) further undermine responses to narco-terrorism. Nonetheless, scholars recommend cooperation between law enforcement and intelligence agencies (Godson, 1994; Mullins and Wither, 2016), and long-term commitments to breaking the nexus apart (Cilluffo, 2000)

Failed States

If the convergence between criminal and terrorists allow them to take over a state, the latter becomes a failed one. Commentators have explained how the events of 9/11 have contributed to reframing the issue of failed states from one of the humanitarian matters to one of global insecurity (Rotberg, 2002a; Patrick, 2007; Innes, 2008; Call, 2008). This dissertation will explain how 9/11 shaped the understanding of failed states in relation to narco-terrorism.

There are multiple definitions of failed states, but none of them is adopted unanimously, and the criteria used to measure state failure vary significantly (Patrick, 2007; Piazza, 2006; Rotberg, 2002a). Before defining failed states, it is helpful to understand what characterises a “functioning” state. Weber (1921) describes nation-states as political entities that monopolise and legitimise violence within their territory. Failed states feature failure to provide essential services (Hehir, 2007) and ensure citizens’ wellbeing (Rotberg, 2002b); inadequate governance capacity, gaps in legitimacy, and internal conflicts (Lamb, 2008); loss of control over borders, corruption and weak infrastructures (Rotberg, 2002a; Zartman 1995: 2-3).

Why Are They Dangerous?

From a practical perspective, failed or rogue states are dangerous because they breed terrorists (Marshall and Gurr, 2005) and transnational criminals (Patrick, 2007: 655; Williams, 2001) and because they are potential safe havens (Lamb, 2008). Safe havens are ungoverned areas that illicit actors exploit to avoid detection (Lamb, 2008: 6; US Department of State, 2006: 156). For instance, illicit actors tap into citizens’ perceived gaps in legitimacy, human insecurity (O’Neil, 2002), and poor social and economic conditions (Gunaratna, 2002) to propose an alternative form of governance (Lamb, 2008: 31). Failed states create political vacuums where illicit actors can step right in and establish a semblance of order. This dissertation will counter this belief by denying a causational relation between failed states and narco-terrorists.

From a theoretical perspective, failed states are dangerous because, in the international system, each state must maintain domestic balance to avoid international chaos caused by the spill-over effect (Rotberg, 2002a: 130). Waltz’s structural realism (1979) supports this position by emphasising the lack of an overarching international authority capable of granting order (Jensen and Elman, 2012: 21). It follows that, as Rotberg (2002a: 130) explained, in such a precarious international system, it is upon every state to ensure that domestic affairs are in order not to tip the international balance. When a failed state becomes a safe haven, the spill-over effect of its failure could weigh upon the entire international system. Similarly, USAID (2003) stated that governance and development failure in a country means that issues ranging from crime and terrorism to health and environmental crises will be even more destructive.

Although scholars have argued that safe havens are a threat to “functioning states”, it remains unclear why states that do not stick to “the western checklist of the sovereign state” prototype become illicit actors’ safe havens. This dissertation will unpack this causational relation.

Do States Fail?

Rotberg explains that failed states with collapsed infrastructure, like Somalia, are rare (2002a: 133). Although some states manifest forms of failure, they are not entirely failed and still retain an extent of control over their territory (e.g. Colombia, Indonesia, and Zimbabwe) (Piazza, 2008). Such states are “weak states” (Rotberg, 2002b), “quasi-state” (Lamback, 2004; Menkhaus, 2003) or “failing states” (Piazza, 2008). Furthermore, scholars agree that ‘failing states’ are more appealing to illicit actors than failed states because they are not as vulnerable to international intervention and because they still offer semi-efficient infrastructures (transportation and telecommunications, access to the global market), which are essential to both terrorists and criminals (Menkhaus, 2003; von Hippel, 2002; Takeyh and Gvosdev, 2002; Patrick, 2007: 655). Conversely, Piazza’s study of failed states as ‘incubators of terror’ (2008) concluded that the higher the degree of state failure, the higher the chances that it will breed terrorists, effectively discarding the possibility that failing states might be more of a threat than failed states.

The notion of failed states as safe havens or sanctuaries for illicit actors does not come without its own set of criticism. Namely, safe havens are based on the Westphalian concept of nation-states (Innes, 2008: 258), which has never applied to the Criminological South. Because there is no agreed-upon definition, vastly diverse states are quickly labelled as ‘failed’ (Call, 2008, 1494-1497). Also, establishing the failure of a state means implying a “prosperous state” state standard that must be met. Such a standard is built upon the Western model, which some failed states like Colombia have never met (Call, 2008: 1499-1500).

International Community’s Response

Since US President Bush swore to smoke terrorists out of their holes (The White House, 2001), Europe (European Council, 2003: 11), Great Britain (PMSU, 2005), Canada (Government of Canada, 2005), and Australia (Australian National Aid Agency, 2006) have all placed safe havens at the top of their agendas. Nonetheless, the existent literature does not address how failed states became an international concern only after America argued about their dangerousness.

Both Lamb (2008) and Rotberg (2002) stress the importance of pairing hard (disarming and defeating) and soft (smart sanctions, freezing overseas accounts, and suspension from international organisations) means when dealing with safe havens in failed states. Premature exit by donors must be avoided, as it could do more damage than no intervention at all (Rotberg, 2002: 140). Notwithstanding, Innes (2008: 259) identified some hardship in combining hard and smart means to intervene in failed states efficiently. Lastly, Brooks (2005) urges against trying to rebuild failed states since the ‘nation-state’ is essentially a Western invention whose standards should not be applied at all costs to every state. Thus, the scholar suggests alternative solutions to state-building such as permanent UN membership as an administration, a loose affiliation with a third-party state, or special status within the EU (Brooks, 2005).

Conclusion

In summary, after evaluating the key academic arguments on narco-terrorism and failed states, this literature review has highlighted that although there is an agreement that 9/11 played a crucial role in redefining both phenomena, there is still no research or theory that investigates the importance of the attacks. Scholars have not analysed how 9/11 impacted narco-terrorism and failed states. Consequently, the literature struggles to define these two concepts and understand their nature. Specifically, there is no distinction between narco-terrorism and the crime-terror nexus. There is a tendency to assume that narco-terrorism occurs, but no study analyses the making of a specific narco-terrorist group. Lastly, although failed states are a contested concept, everyday praxis assumes that non-western states are bound to become safe havens for illicit actors.

Case Studies

This section will look at the case studies of Afghanistan and Colombia.

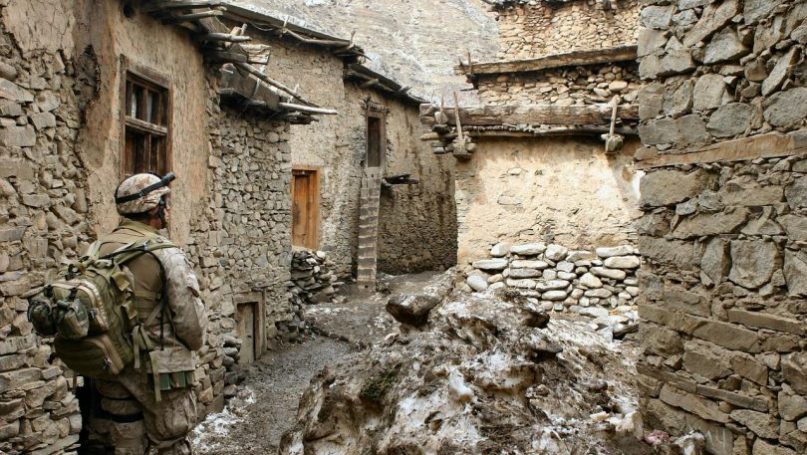

Case Study: Afghanistan

Afghanistan gained independence in 1919 after the Anglo-Afghan wars (Rubin, 2006; Ayub and Kuovo, 2008). The Soviet invasion in the 1970s, the US support of the Mujahideen, and the complete withdrawal of American and Russian forces after the end of the Cold War contributed to further damage to this already conflict-torn nation (Ayub and Kuovo, 2008; Lister, 2007). As power became decentralised, warlords came to control larger areas (Giustozzi, 2003; Rubin 1995). In such a chaotic context, the Taliban consolidated their power; meanwhile, bin Laden strengthened his regime in Afghanistan (Ayub and Kuovo, 2008). According to Katzman (2008: 5), the Taliban are a group of Islamic clerics and students that opposed the idea of internal conflict among Mujahideen and the corruption of the Rabbani government. The Taliban’s primary source of income is the cultivation, taxation, and trade of the opium poppy (Azami, 2018).

The Outset of the War on Terror

The 9/11 attacks proved to the US that even “weak” states could be a security concern (Rubin, 2006; Rotberg, 2002a; Patrick, 2007; Innes, 2008; Call, 2008), and the immediate reaction was to persuade the Taliban to extradite the terrorist suspects responsible for the attacks (Misra, 2004a: 108). However, the Taliban’s lack of cooperation reinforced the US’s idea that the Taliban were protecting the culprits; thus, validating the existence of a crime-terror nexus. The Bush Administration’s next step was to overthrow the Taliban (Katzman, 2010). This decision might be understood as an attempt to weaken the link between the Taliban and bin Laden. The USA declared war against Afghanistan (War on Terror) and framed it as an act of self-defence (Connah, 2021: 72), which was approved by the UN Security Council in Resolution 1368, allowing the US to “combat by all means threats to international peace and security caused by terrorist acts” (UNSC, 2001). To create a Taliban-free and more cooperative environment, the US also aimed at strengthening the economic, social, political, and security sectors in Afghanistan (Tarnoff, 2010). Nevertheless, USA’s attempts to simultaneously address security concerns and development issues have sparked debates around the legitimacy of the means adopted to curtail the terrorist threat and prevent Afghanistan’s failure as a state (Ayub and Kuovo, 2008).

Narco-terrorism in a “Rogue” Afghanistan

Aasen (2019: 141) points out that although violence and narcotics have had a long-standing relationship in Afghanistan, they only became a threat after 9/11. Undeniably, the US willingly overlooked the Mujahideen’s use of profits from the illegal narcotics trade to finance their resistance against the Soviets (Jalalzai, 2005: 9; MacDonald, 2007: 88; Shanty, 2011: 23; Rashid, 2010) but suddenly become opposed to the “cooperation” between terrorists and narco-traffickers after the attacks of 9/11. This rapid change of heart is linked to the Taliban’s refusal to extradite the 9/11 perpetrators. It follows that when the illicit drug trade is used to finance initiatives that fit the US agenda, it is permissible. Nonetheless, when the drug trade is used to support anti-American activities, it becomes a security threat. Such reasoning would almost sound legitimate (from a US domestic perspective) if it did not blatantly use dangerous double standards. Indeed, it is upon those double standards that US President Bush could construct the War on Terror as a global security issue.

Notably, President Bush identified a case of narco-terrorism in the Taliban-backed al-Qaeda terrorist training camps and military installations in Afghanistan (The Washington Post, 2001). Moreover, because of the interplay between al-Qaeda and the Taliban regime, the US viewed Afghanistan as a “rogue state” (US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, 2000: 1); and, as such, it embodied a challenge to the international community’s norms and values (Aasen, 2019: 147). Therefore, the US’s behaviour suggests that the Taliban are not a threat because they oversee the Afghan opium trade but because their association with terrorists confirms the belief that failed/rogue states breed a new kind of threat – narco-terrorism (Tsui, 2015: 75). The latter becomes a global danger because it threatens Western interests and, therefore, requires an extreme militarised approach; hence, the War on (Narco-)Terror.

What makes the War on (Narco-)Terror even more controversial is that the “new kind of threat” President Bush and the international community were so worried about did not exist. Evidence shows no link between bin Laden and the Taliban through the narcotics trade (Burke, 2003: 45; The 9/11 Commission, 2004: 171; Gomis, 2015: 7). Considering this, President Bush’s rejection of the Taliban’s offer to hand over bin Laden to a neutral country and to negotiate American troops’ withdrawal from Afghanistan (Robertson and Wallace, 2001; The Guardian, 2001) proves that The War on (Narco-)Terror was not just about preventing a failed state from becoming a safe haven for narco-terrorists.

From Counterterrorism to State-building?

Security is undoubtedly the main logic underpinning Afghanistan’s invasion. However, narco-terrorism is not the only threat to US security. Rosato and Schuessler (2011) posit that the balance against rival powers is critical to achieving security. Moreover, a state can achieve a greater level of security by becoming a hegemon (Mearsheimer, 2001). Through a realist lens, because the US was already a regional hegemon before 9/11 (Mearsheimer, 2001), the rise of other potential regional hegemons would have threatened its position and the international system’s status quo. Because the US aspired to become a global hegemon, the economic, political, and military rise of China and India in Asia constituted a threat to US supremacy. Gartenstein-Ross (2014) and Landler and Risen (2017) explained that China’s plan to exploit Afghanistan’s raw mineral and natural resources was a direct threat to the US economic interests.

Similarly, India is considered another aspiring regional hegemon (Rahman, 2019), and it ranks fourth in military power (Global Fire Power, 2021). Thus, it challenges American supremacy in the region, as it could be a significant military threat. Military and economy are two of the five sectors (Buzan, 1991: 19) that, if threatened, undermine a state’s sovereignty (Weaver et., 1993). Consequently, the defensive realist explanation that the US’s invasion of Afghanistan is motivated by only security concerns is not sufficient. In an offensive realist optic, which emphasises maximising power (Mearsheimer, 2001), the US presence in Afghanistan serves to keep the rise of China and India in check. Specifically, the US is acting as an onshore balance against China by keeping its troops in Afghanistan with the intent of state-building; and as an offshore balance against India by supporting Pakistan, its main competitor (Mearsheimer and Walt, 2016; Rahman, 2019). The implications of this offensive realist argument for this dissertation are that narco-terrorism may not be that much of a pressing threat as it was constructed to be since no evidence confirms a crime-terror nexus in Afghanistan.

“Just” Intervention?

As mentioned above, the US War on Terror in Afghanistan was authorised by Resolution 1368 (Connah, 2021: 72). However, Resolution 1368 does not explicitly authorise an invasion (UNSC, 2001). Thus, the US Congress’s endorsement of the Authorization for Use of Military Force of 2001 (AUMF) (US Congress, 2001) shows that the US intervention was nothing more than a unilateral use of force in self-defence (Ratner, 2002: 908; Cortright, 2011: 13). Afghanistan’s invasion was a war, and, for it to be legitimate, it must adhere to the Just War principles. Just War theory is a compromise between the pacifist view that categorically banishes war and the realist inevitability of armed conflict. According to ius ad bellum, war is justifiable if it is in self-defence, has a chance of success, and is a state’s last resort (Crawford, 2003: 7). Conversely, ius ad bellum calls for the proportionality of targets during attacks and discrimination (Whetham, 2010: 80-81).

If one accepts the self-defence narrative fostered by Bush’s Presidency, the War on Terror is justifiable in light of 9/11. However, this dissertation has already explored how the US used Afghanistan to assert its presence and curb China and India’s rise in the region. Under the uncorroborated pretence of narco-terrorism, invading a state to prevent other states from fully developing their military and economic capabilities is not just. In terms of war as a last resort, President Bush has specified that he was not interested in negotiating with the Taliban or al-Qaeda (The Guardian, 2001) and that “America’s best defense is a good offense” (NSC, 2002: 6). Thus, it seems unlikely that any non-military action would have been considered. The American support for the Northern Alliance’s ruthless methods (Misra, 2004b; Bird and Marshall, 2011), the fourteen thousand civilians killed between 2006 and 2014 only (Downes and Monten, 2013: 91), and the use of violence and torture (Kaldor, 2013: 166) are proof enough to believe that the US has not met the ius in bello criteria in Afghanistan.

The fact that the Bush Administration justified disproportionate civilian casualties by claiming that they were “unintended” and by reminding us of the humanitarian assistance provided by US airdrops (Crawford, 2003: 13) equals saying that if the perpetrators of 9/11 had claimed to have “accidentally” crashed an aeroplane into the twin towers, and had helped “clean up the mess”, the US would not have invaded Afghanistan. In summary, Afghanistan’s invasion was presented as a war to prevent Afghanistan from becoming a narco-terrorists’ safe haven. However, due to the paucity of narco-terrorism evidence, it is more accurate to believe that the US used the War on (Narco-)Terror to consolidate its interests against rising powers in the region. In retrospect, this dissertation posits that what undermined the US legitimacy in Afghanistan was the humanitarian cause’s rhetoric (Ayub and Kuovo, 2008). State- and democracy-building were never in the US intentions as much as hegemony and counterterrorism.

Case Study: Colombia

Colombia has been labelled as a failing or weak state (Rotberg, 2003; Brooks, 2005; Montañez, 2017). From 1948 to the 1960s, the country was torn by a civil war (La Violencia) instigated by the government’s assassination of political activists (Chomsky, 2000). Additionally, from the 1960s to the 1980s, the guerrillas’ communist insurgency and the Cold War contributed to worsening Colombia’s feeble stability (Dube and Naidu, 2015). The FARC and the ELN came into existence during the civil war (Livingstone, 2004; Dube and Naidu, 2015). Both groups sought to overthrow the Colombian government favouring a Marxist regime and land redistribution (Montañez, 2017). The FARC notoriously used kidnapping and drug trafficking to fund their campaign (Vélez, 2001; Shifter, 1999; Rosen, 2014).

Plan Colombia and the Narco-terrorist Connection

Colombia is the world’s biggest producer of cocaine, and the US is its most significant consumer (UNODC, 2014). Such circumstances influence the US-Colombia relationship. Plan Colombia (2000-2006) is the law aid package approved by President Bush that granted Colombia US $7.5 billion to counter drug trafficking and promote state development (Franz, 2017). The Bush Administration’s key objectives included eradication efforts to reduce illicit coca crops, which would, in turn, reduce insurgent violence and encourage social justice (DNP, 2006; Mejía et al., 2011). The assumption that curbing cocaine production will reduce violence is already constructing a narco-terrorist narrative. Indeed, according to the US, the FARC’s success was rooted in the cocaine trade, their crucial source of income (US Department of State, 2002).

Plan Colombia did not work (Franz, 2016; Hylton, 2010; Mondragón, 2007; Marcella, 2001). One of the reasons was the Plan’s highly militarised approach (Crandall, 2002; Aviles, 2008). Indeed, 61% of the aid went towards strengthening the Colombian military (Marcella, 2001: 8). The emphasis on Colombian Security Forces has also been linked to human rights violations (Farthing, 2006: 74). Moreover, human losses (Hylton, 2010: 111; Dion and Russler, 2008: 418) and displacement (Marcella, 2001: 1; Hylton, 2010: 109) prevented Plan Colombia from meeting its development expectations. Like in Afghanistan, the US readily promised Colombia development strategies without ever putting much effort into restoring Colombia’s institutions, except its security apparatus. The latter, however, was unable to counter the narco-terrorist threat, considering that FARC’s attacks increased after Plan Colombia (ICRC, 2009).

This dissertation argues that the US devised Plan Colombia as an essential pillar of the War on Drugs; however, after 9/11, the US used the narco-terrorist narrative to design the FARC as an Foreign Terrorist Organization (responsible for civil violence and the cocaine trafficking) and wage a “Latin War on Terror”, which matched the current American attitude towards foreign policy (Stokes, 2003: 579). According to the US agenda, the FARC was the main narco-terrorist actor in Colombia, and by merging counter-narcotics and counterinsurgency efforts through Plan Colombia, they would have killed two birds with one stone.

The Crime-Terror Paradox

The FARC turned to the illicit drug trade in the 1990s to fund their struggle against the Colombian right-wing paramilitaries (BACRIM) (Montañez, 2017). The guerrillas could assert their position within the cocaine business only after the US dismantled the Medellin and Cali drug cartels, monopolising the cocaine trade (Peceny and Durnan, 2006). Academically speaking, the FARC is a fitting example of what Makarenko (2004a) and Mullins and Wither (2016) defined as hybrid groups, starting with a solely political (or economic) agenda and gradually moving towards the opposite end of the spectrum. Thus, the crime-terror nexus in Colombia is not a concrete partnership between politically- and profit-oriented actors. In this case, narco-terrorism consists of one insurgent group seeking economic gains to fund its purpose.

As aforementioned, the US had condoned similar behaviours in the past, when the CIA disregarded Mujahideen’s involvement in the heroin trade during the Cold War (Vornberger, 1978). The Colombian instance of narco-terrorism promotes the notion that it is entirely at America’s discretion to decide whether it is an instance of narco-terrorism whenever an insurgent group becomes involved in the drug trade, effectively nullifying the meaning of the concept itself and making it vulnerable to the current President’s whims. Consequently, this dissertation argues that the Colombian case reinforces the belief that narco-terrorism is not a criminological phenomenon as much as it is a label strategically attached to problematic actors to serve the current political administration’s interests.

Even though Plan Colombia existed to tackle the devastatingly damaging effects of the illicit drug trade, the US counter-narcotics initiative did not target the key responsible for cocaine distribution and violence in Colombia: the paramilitaries. Although not officially backed by the government, the paramilitaries received support from the army and the police in Colombia (Dube and Naidu, 2015). As aforementioned, most of the US’s contribution to Plan Colombia went to the Colombian army and police, which were (and still are) collaborating with the paramilitaries (Avilés, 2008: 412; Stokes, 2003: 580). The paramilitaries are not only notable narco-traffickers (Vargas Meza, 2000: 22; Echandía Castilla, 2001) but also responsible for massacres against the civil population (Avilés, 2008: 413; Richani, 2002: 120-121; Ballvé, 2009; Stokes, 2003: 581). The US deliberately supported right-wing groups that profited from the drug trade (as much as the FARC) and committed atrocities against the civil population. The paramilitaries were listed as FTOs (Ballvé, 2009), just like the FARC, but were not considered narco-terrorists. Thus, the War on Drugs turned into a US-sponsored Latin War of Terror, considering the extent of violence allowed against Colombian non-combatants.

Whose Interests?

According to Hylton (2010: 108), the paramilitaries were employed to pacify Colombia quickly and efficiently, replacing the Colombian State and contradicting any state-building effort. What security concerns pushed the US into seeing the paramilitaries as a resource instead of a threat, considering their role in the cocaine trade? This dissertation maintains that neither narco-terrorism nor drugs, nor state-building were at the forefront of the American agenda during Plan Colombia.

Contrary to Chomsky’s theory (1985) which claims that US counterinsurgency campaigns in Latin America sought to curtail the threat of Soviet subversion bred by the socio-economic instabilities; this dissertation sides with the argument that American interventions in Latin America concerned the spread of Capitalism (Kolko and Kolko, 1972: 23), rather than Soviet containment. This does not imply that the leftist groups in Colombia were unimportant to the US. However, claiming that narco-terrorism in Colombia was enough of a threat to warrant military intervention and state-building efforts is far-fetched. Especially considering that the FARC were constructed as narco-terrorists only after 9/11, so the US could lead its asymmetric warfare using non-state actors (paramilitaries) and private security companies (Rochlin, 2011: 734), limiting their accountability.

Plan Colombia was the US’s imperialist effort to dominate the Andean region’s production of oil, which became a vital American interest because of the Middle East instability (Klare, 2000: 1-2; Petras, 2001), and to create a transnational state (Robinson, 2004: 91) stable enough for America and trans-national corporations’ investments. To achieve such a result, the US chose to target exclusively guerrilla violence, framing it as narco-terrorism, because guerrilla groups ascribed to a Marxist ideology, which, by definition, opposes capitalism and neoliberal economies. Conversely, the right-wing paramilitaries were given authority to conduct atrocities against civilians and profit from the cocaine trade. The US constructed a case of narco-terrorism in Colombia to cloak military interventions under the name of “state-building” and pursue its imperialistic goals.

Discussion

Now that this dissertation has explored the central academic positions around narco-terrorism and failed states and has analysed the two case studies, it is time to conclude. Hence, what is narco-terrorism? How did it become part of mainstream discussions around danger and security? Furthermore, do failed states breed narco-terrorism?

Narco-terrorism is a fabrication. To understand why this section will now link the critical academic theories to the case studies’ empirical findings.

Scholars claim that there is insufficient evidence to unpack narco-terrorism (Makarenko, 2004a; Bjornehed, 2004: 308; Schmid, 2005; Wardlaw, 1998: 11; Mullins and Wither, 2016: 65; Reitano et al., 2017), so much so that they struggle to agree on a definition. Nevertheless, the US invaded Afghanistan and Colombia, killing and displacing civilians in the process, in the name of something that cannot be defined and the existence of which cannot be corroborated. Why? To answer this question, it must be considered that narco-terrorism has gained resonance only after 9/11 (Gomis, 2015).

How did 9/11 affect the international system, and how does that relate to narco-terrorism and failed states? The fateful attack introduced a new phase of warfare by adding a global dimension to terrorism (Buffaloe, 2006). Terrorism is an enemy that plays by no rules and knows no international conventions; combating terrorism means fighting “asymmetric” warfare (Buffaloe, 2006). Such was the impact of 9/11 that it challenged core values, notions, and routine practices that shaped America’s identity (Schelenz, 2017), disrupting not only America’s security but also its ontology. According to the Ontological Security Theory (OST), states seek both physical and ontological security. Where realists argue that states focus on survival, OST scholars counter that states are equally interested in ensuring that the self will prevail in the international order (Mitzen, 2006: 342-344). Lack of identity means uncertainty and absence of self-conception (Mitzen, 2006: 345) and because identities symbolise interests (Hopf, 1988: 175), a state with no identity and no interests loses its agency.

The way the US went about reconstructing its identity is vital to understanding why narco-terrorism is a fabrication.

The keyword in this “reconstruction of identity” process is fear. Unquestionably, 9/11 caused a great extent of fear in the US. Nevertheless, what is fear? Fear is an anachronistic construction that transcends epochs but is influenced by them (Mantilla-Valbuena, 2008). 9/11 is part of a globalised era where fear comes from diffused and uncontrollable dangers (Mantilla-Valbuena, 2008). However, fear is also a “fortuitous factor”, instrumentalised by powerful entities (Mantilla-Valbuena, 2008).

How did the US instrumentalise fear to re-establish its identity? From Beck’s (2012) risk society to Bauman’s (2006) recycling of susceptibility to danger, fear acquires a structural function that lends itself to political domination and social control (Mantilla-Valbuena, 2008). The emphasis is now on political domination. A lesson learnt from Afghanistan and Colombia is that the War on (Narco-)Terror and Plan Colombia cloaked hegemonic and expansionistic goals. Afghanistan was an operational base to counterbalance the growth of China and India, and Colombia – to ensure the spread of a neoliberal capitalist ideology in Latin America and undermine the communist one in Venezuela and Nicaragua. Going back to the literature, Wardlaw warned that narco-terrorism might indeed become a propaganda tool to pursue political agendas by merging two considerable security threats, such as drug trafficking and terrorism (Wardlaw, 1988: 6).

Why would someone want to “join the forces of evil” and merge two threats already dangerous on their own? Even though conveying fear towards specific dangers is a great tool to achieve political power, creating a whole new super-threat seems hyperbolic, even for the US. Except that there is a way to profit from danger. Looking at the case studies, there is a predominant element in both interventions – the heavily militarised approach. How can militarisation and wars benefit the US? Ten of the world’s largest defense contractors are American companies (Stebbins and Comen, 2019), and, right after 9/11, Defense Department contracts reached $147.9 billion, and the spending kept going up every year (Face the Facts, 2013). Moreover, “one-third of the members of the Defense Subcommittee of the Appropriation Committee own stocks in top defense contractors” (Shaw and Moore, 2020). The US benefits from the fabrication of narco-terrorism because it was constructed as a lucrative business, which has allowed the latter to execute its imperialistic agenda by using discourses of danger and fear while simultaneously matching the post-Cold War globalised neoliberalist international trend. Thus, narco-terrorism is a fabrication and not a super threat.

The notion of “failed states”, like narco-terrorism, emerged after 9/11 (Rotberg, 2002a). Such an argument is inherently flawed because it is unlikely that certain states simultaneously and suddenly “failed” after 9/11. Were they “functioning states” before? Or were they simply not on anyone’s agenda? Although the states that fail only do so when put against the Western standards (Innes, 2008; Call, 2008) (their existence will momentarily be accepted for argument’s sake). Do they breed narco-terrorism? Having argued that narco-terrorism is a fabrication, it must follow that there is nothing to breed. Nevertheless, scholars have alluded to a crime-terror nexus based on fleeting and instrumental interactions (Schmid, 2005; Dishman, 2001; Bjornehed, 2004; Mullins and Wither, 2016; Reitano et al., 2017; Makarenko, 2004a). Since there is evidence of occasional cooperation among terrorists and criminals, and since narco-terrorism is a fabrication, it is logical to distinguish the latter and the crime-terror-nexus, which describes the relationship or lack thereof between terrorist and criminal actors. Whether or not states that fail to measure up to Western standards breed crime-terror nexuses is beyond the purpose of this dissertation.

Conclusively, this dissertation argues that narco-terrorism is a fabrication that sprung in the post-9/11 context of ontological insecurity that required the US to re-frame its identity in a globalised international order. Terrorism and drug trafficking have fallen victim to the US’s identity quest, which used fear and danger to merge the two threats and fabricate a super-threat that justified the heavy militarisation of responses. Such militarised interventions fortified war-profiteering and an imperialistic foreign agenda cantered around the hegemonic spread of a neoliberal capitalist ideology. To answer the questions that opened this section, this dissertation contends that narco-terrorism is a multisectoral label, the use of which requires securitisation (Buzan et al., 1998) of a specific crime-terror nexus by those placed to do so through the construction of a narrative.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this dissertation has used a Case Study approach to evaluate whether failed states breed narco-terrorism and to re-frame the latter’s ontology and epistemology. The literature review revealed the key positions, theories and gaps concerning both phenomena. The two case studies, Afghanistan and Colombia, were essential to contextualise the previous section’s theoretical framework and analyse the dynamics at play in two instances of narco-terrorism in one “failed” and one “failing” state. Overall, this dissertation has argued for a crucial difference between the crime-terror nexus and narco-terrorism, with the latter being a fabrication. Although failed states might entail a crime-terror nexus, they do not breed narco-terrorism due to a lack of centralised authority monopolising power and force. If there is no causational relation between the two phenomena, some light must be shed upon what compelled the US’ interventions in Afghanistan and Colombia in the context of this study. Drawing upon constructivism and OST, this dissertation posits that narco-terrorism was a by-product of the US’s search for identity. The US weaponised discourses of fear and danger to fabricate a narco-terrorist lucrative business in Afghanistan and Colombia and re-calibrate its foreign agenda towards hegemonic and expansionistic aims.

Limitations

Due to the impossibility of travelling to Afghanistan and Colombia to conduct primary research, this study has relied exclusively on secondary data analysis. However, thanks to the cross-checking process among numerous sources and the qualitative nature of the research, this study has not been compromised in any way by its methodology.

Wider Implications: Looking Forward

One element outlined by this study is the ubiquitous presence of state- or peace-building operations initiated but not accomplished by the US in Afghanistan and Colombia. The contexts in which such operations have been attempted is indicative of their coefficient of success. Indeed, it can be argued that because the US’s agenda was interest-led, and state- or peace-building was never part of those interests neither in Afghanistan nor in Colombia as much as it was a pretence to legitimise lengthy and drawn-out interventions. Such a scenario recalls Galtung’s Roman pax (1981), which served the interests of those in power to preserve the status quo. Future research could look at how power relations within the global system impact upon state- or peace-building. Specifically, it would be beneficial to understand if state- or peace-building is possible when a powerful donor with hegemonic aspirations and a valuable receiver is involved. This dissertation’s findings suggest that a negative peace or absence of violence (see Galtung, 1996) might be more likely instead.

References

Aasen, D. (2019) Constructing Narcoterrorism as Danger: Afghanistan and the Politics of Security and Representation (Doctoral dissertation, University of Westminster). Available at: https://tinyurl.com/2p8nbw67. [Accessed 16 February 2021].

Anderson, T. S. (2004) Transnational Terror and Organized Crime: Blurring the Lines. SAIS Review, 24(1): 50-52.

Austin, J. L. (1962) How to Do Things with Words. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Australian National Aid Agency (AusAID) (2006) Australian Aid: Promoting Growth and Stability-White Paper on the Australian Government’s Overseas Program. Canberra: Government of Australia.

Aviles, W. (2008) US Intervention in Colombia: The Role of Transnational Relations. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 27(3): 410-429.

Ayub, F. and Kouvo, S. (2008) Righting the Course? Humanitarian Intervention, the War on Terror and the Future of Afghanistan. International Affairs, 84(4): 641-657.

Azami, D. (2018) Afghanistan: How does the Taliban make money?. BBC, 22 December. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-46554097. [Accessed 15 February 2021].

Ballvé, T. (2009) The Dark Side of Plan Colombia. The Nation, 15: 22-32.

Bauman, Z. (2006) Liquid Fear. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Beck, U. (2012) Global risk society. The Wiley‐Blackwell Encyclopedia of Globalization.

Bird T. and Marshall, A. (2011) Afghanistan: How the West Lost its Way. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Björnehed, E. (2004) Narco-terrorism: The Merger of the War on Drugs and the War on Terror. Global Crime, 6(3-4): 305-324.

Brooks, R. E. (2005) Failed States, or the State as Failure?. The University of Chicago Law Review, pp. 1159-1196. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4495527. [Accessed 26 January 2021].

Buffalaoe, D. (2006) Defining Asymmetric Warfare. The Association Of The United States Army, 1 October. Available at: https://www.ausa.org/publications/defining-asymmetric-warfare. [Accessed 17 April 2021].

Burke, J. (2003) Al Qaeda: Casting A Shadow of Terror (London: IB Tauris). Measured and insightful analysis of the origins and motives of al-Qaeda.

Burton, D. (2000) The Use of Case Studies in Social Science Research. Research training for social scientists, pp. 215-225.

Buzan, B. (1991) People, States and Fear: An Agenda for International Security Studies in the Post-Cold War Era. Essex: Longman.

Buzan, B., Wæver, O., Wæver, O. and de Wilde, J. (1998) Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Call, C. T. (2008) The Fallacy of the ‘Failed State’. Third World Quarterly, 29(8): 1491-1507.

Calvani, S. (2004) United Nations Perspective. Crime-Terrorism Nexus: How does it really work, pp. 6-14.

Campbell, D. (1998) Writing Security: United States Foreign Policy and the Politics of Identity. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) (1991) Commentary No.13, Terrorism and the Rule of Law: Dangerous compromise in Colombia. Canadian Security Intelligence Service.

Chomsky, N. (1985) Turning the Tide: US Intervention in Central America and the Struggle for Peace. Boston: South End Press.

Chomsky, N. (2000) Rogue States: The Rule of Force in World Affairs. London: Pluto Press.

Chouvy, P. A. (2004) Narco-Terrorism in Afghanistan. Terrorism Monitor, 2(6): 7-9.

Cilluffo, F. (2000) The Threat Posed from the Convergence of Organized Crime, Drug Trafficking, and Terrorism. Testimony of the Deputy Director, Global Organized Crime Program, Director, Counterterrorism Task Force, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, Washington (DC). to the US House Committee on the Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime.

Connah, L. (2021) US Intervention in Afghanistan: Justifying the Unjustifiable?. South Asia Research, 41(1): 70-86.

Corti, L., Thompson, P. and Seale, C. (2006) Secondary Analysis of Archived Data. Qualitative Research Practice: Concise Paperback Edition. SAGE Publications Ltd, London, pp. 297-313.

Cortright, D. (2011) Ending Obama’s War: Responsible Military Withdrawal from Afghanistan. Boulder: Paradigm.

Crandall, R. (2002) Driven by Drugs: US Policy toward Colombia. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Crawford, N. C. (2003) Just War Theory and the US Counterterror War. Perspectives on Politics, pp. 5-25.

Curtis, G. E. and Karacan, T. (2002) The Nexus Among Terrorists, Narcotics Traffickers, Weapons Proliferators, and Organized Crime Networks in Western Europe. In The Library of Congress, December.

Denscombe, M. (2014) The Good Research Guide: For Small-scale Social Research Projects. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

Dillon, M. (1996) Politics of Security: Towards a Political Philosophy of Continental Thought. London: Routledge.

Dion, M. L. and Russler, R. (2008) Eradication Efforts, the State, Displacement and Poverty: Explaining Coca Cultivation in Colombia during Plan Colombia. Journal of Latin American Studies, 40(3): 399–421.

Dishman, C. (2001) Terrorism, Crime, and Transformation. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 24(1): 43-58.

DNP (2006) Balance Plan Colombia: 1999–2005. Bogotá: Departamento Nacional de Planeación (DNP).

Doty, R. L. (1996) Imperial Encounters: The Politics of Representation in North-South Relations. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Downes, A. B. and Monten, J. (2013) Forced to be Free? Why Foreign-Imposed Regime Change Rarely Leads to Democratization. International Security, 37(4): 90–131.

Dube, O. and Naidu, S. (2015) Bases, Bullets, and Ballots: The Effect of US Military Aid on Political Conflict in Colombia. The Journal of Politics, 77(1): 249-267.

Echandía Castilla, C. (2001) La Violencia en el Conflicto Armado Durante los años 90’. Revista OPERA Universidad Externado de Colombia, 1: 229–46.

Ehrenfeld, R. and Kahan, M. (1986) The Narcotic-Terrorism Connection. Wall Street Journal, 10 February.

European Council (2003) A Secure Europe in a Better World: European Security Strategy. Brussels: European Union.

Face the Facts (2013) Fed Contractors Profit from War on Terror, 1 March. Available at: https://facethefactsusa.org/facts/fed-contractors-profit-war-terror/. [Accessed 17 April 2021].

Farthing, L. (2006) The Drug War in The Andes. Ithaca, New York. Available at: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiM7-Xp86jvAhVAQUEAHTk2CS8QFjABegQIAxAD&url=http%3A%2F%2Fain-bolivia.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2FdrugwarCompleteLF.doc&usg=AOvVaw0RBRpVJD54DuSKuz1O6_xH. [Accessed 10 March 2021].

Fossey, E., Harvey, C., McDermott, F. and Davidson, L. (2002) Understanding and Evaluating Qualitative Research. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(6): 717-732.

Franz, T. (2016) Plan Colombia: Illegal Drugs, Economic Development and Counterinsurgency – A Political Economy Analysis of Colombia’s Failed War. Development Policy Review, 34(4): 563-591.

Franz, T. (2017) The Legacy of Plan Colombia. Oxford Research Group. Available at: https://www.oxfordresearchgroup.org.uk/blog/the-legacy-of-plan-colombia. [Accessed 19 March 2021].

Galtung, J. (1981) Social Cosmology and the Concept of Peace. Journal of Peace Research, 17(2): 183-199.

Galtung, J. (1996) Peace by Peaceful Means: Peace and Conflict, Development and Civilisation. Oslo: PRIO.

Gartenstein-Ross, D. (2014) China No Substitute for U.S. Involvement Over Afghanistan. CNN, 29 October. Available at: https://globalpublicsquare.blogs.cnn.com. [Accessed 17 February 2021].

Giustozzi, A. (2003) Respectable Warlords? The Politics of State-building in Post-Taliban Afghanistan. Working Paper no. 33. London: Crisis States Research Centre, London School of Economics.

Global Fire Power (2021) 2021 Military Strength Ranking. Available at: https://www.globalfirepower.com/countries-listing.asp. [Accessed 17 February 2021].

Godson, R. (1994) Crisis of Governance: Devising Strategy to Counter International Organised Crime. Terrorism and Political Violence, 6(2): 163-177.

Gomis, B. (2015) Demystifying ‘Narcoterrorism’. Swansea: Global Drug Policy Observation brief.

Government of Canada (2005) Canada’s International Policy Statement: A Role of Pride and Influence in the World. Available at: http://aix1.uottawa.ca/~rparis/IPS_2005.pdf. [Accessed 26 January 2021].

Gunaratna, R. (2002) Terrorism in the South before and after 9/11: An Overlooked Phenomenon. Responding to Terrorism: What Role for the United Nations, pp. 32-34.

Hammond, M. and Wellington, J. (2020) Research Methods: The Key Concepts. Taylor and Francis Group.

Heaton, J. (2008) Secondary Analysis of Qualitative Data: An Overview. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung, pp. 33-45.

Hehir, A. (2007) The Myth of the Failed State and the War on Terror: A Challenge to the Conventional Wisdom. Journal of Intervention and State Building, 1(3): 307-332.

Hopf, T. (1998) The Promise of Constructivism in International Relations Theory. International security, 23(1): 171-200.

Hox, J. J. and Boeije, H. R. (2005) Data Collection, Primary versus Secondary.

Hutchinson, A. (2002) International Drug Trafficking and Terrorism. Testimony Before the Senate Judiciary Committee Subcommittee on Technology, Terrorism, and Government Information. Available at: http://20012009.state.gov/p/inl/rls/rm/9239.htm. [Accessed 22 December 2020].

Hylton, F, (2010) Plan Colombia: The Measure of Success. Brown Journal of World Affairs, 17(1): 99-115.

Innes, M. A. (2008) Deconstructing political orthodoxies on insurgent and terrorist sanctuaries. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 31(3): 251-267.

International Committee of the Red Cross (2009) Annual Report on Colombia 2009. Available at: https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/other/annual-report-2009-colombia-icrc.pdf. [Accessed 10 March 2021].

Jalalzai, M. K. (2005) Narco-terrorism in Afghanistan. Lahore: Nasir Bakir Press.

Jensen, M. A. and Elman, C. (2012) Realisms. In Williams, D. and McDonald, M. (eds) Security Studies: An Introduction, 3rd edn. Routledge, pp. 17-32.

Kaldor, M. (2013) New and Old Wars: Organized Violence in a Global Era, 3rd edn. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publications.

Katzman, K. (2010) Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and US Policy. Library of Congress Washington DC, Congressional Research Service.

Keohane, R. O. (1989) International Institutions and State Power: Essays in International Relations Theory. Boulder: Westview Press.

Klare, M. (2000) Detras del Petroleo Colombiano: Intenciones Ocultas. Equipo Nikzor. Available at: http://www.derechos.org/nizkor/colombia/doc/plan/klare.html. [Accessed 15 March 2021].

Kolko, J. and Kolko, G. (1972) The Limits of Power. The World and United States Foreign Policy, 1945-1954. New York: Harper and Row.

Lamb, R. D. (2008) Ungoverned areas and threats from safe havens. Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defence for Policy Planning Washingto DC. Available at: https://spp.umd.edu/sites/default/files/2019-07/ugash_report_final.pdf. [Accessed 26 January 2021].

Lambach, D. (2004) The Perils of Weakness: Failed States and Perceptions of Threat in Europe and Australia. In New Security Agendas: European and Australian Perspectives conference at the Menzies Center, Kings College, London (pp. 1-3).

Landler, M. and Risen, J. (2017) Trump Finds Reason for the U.S. to Remain in Afghanistan: Minerals. The New York Times, 25 July. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/25/world/asia/afghanistan-trump-mineral-deposits.html. [Accessed 17 February 2021].

Lister, S. (2007) Understanding state-building and local government in Afghanistan. Working Paper no. 14, Crisis States Research Centre.

Livingstone, G. (2004) Inside Colombia: Drugs, Democracy and War. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

MacDonald, D. (2007) Drugs in Afghanistan: Opium, Outlaws and Scorpion Tales. London: Pluto Press.

Makarenko, T. (2004a) The Crime-terror Continuum: Tracing the Interplay between Transnational Organised Crime and Terrorism. Global Crime, 6(1): 129-145.

Makarenko, T. (2004b) “South Central Asia: The Organised Crime Angle” presented at The Crime-Terror Nexus: Hoe does it really work?

Mantilla-Valbuena, S. C. (2008). Más Allá del Discurso Hegemónico: Narcotráfico, Terrorismo y Narcoterrorismo en la Era del Miedo y la Inseguridad Global. Papel Politico, 13(1): 227-260. Available at: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0122-44092008000100008&lng=en&tlng=es. [Accessed 17 April 2021].

Marcella, G. (2001) Plan Colombia: The Strategic and Operational Imperatives. Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College.

Marshall, M and Gurr, T. R. (2005) Peace and Conflict 2005. College Park, MD: Center for International Development and Conflict Management.

Mearsheimer, J. J. (2001) The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York, NY: Norton.

Mearsheimer, J. J. and Walt, S. M. (2016) The Case for Offshore Balancing: A Superior U.S. Grand Strategy’, Foreign Affairs, 95(4): 70–83.

Mejía, D. and Restrepo, P. (2011) Do Illegal Drug Markets Breed Violence? Evidence from Colombia. Working Paper. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes.

Menkhaus, K. (2003) Quasi States, Nation-Building and Terrorist Safe Havens. Journal of Conflict Studies, 23(2): 7-23.

Miller, A. H. and Damask, N. A. (1996) The dual myths of ‘narco‐terrorism’: How myths drive policy. Terrorism and Political Violence, 8(1): 114-131.

Misra, A. (2004a) Afghanistan: The Labyrinth of Violence. Cambridge: Polity.

Misra, A. (2004b) Afghanistan: The Politics of Post-War Reconstruction. Conflict, Security and Development, 2(3): 5-27.

Mitzen, J. (2006) Ontological Security in World Politics: State Identity and the Security Dilemma. European Journal of International Relations, 12(3): 341-370.

Mondragón H. (2007) Democracy and Plan Colombia. NACLA Report on the Americas, 40(1): 42-44.

Montañez, J. C. R. (2017) Fifteen Years of Plan Colombia (2001-2016) The Recovery of a Weak State and the Submission of Narco-terrorist Groups?. Analecta Política, 7(13): 315-332.

Mullins, S. and Wither, J. K. (2016) Terrorism and Organized Crime. Connections, 15(3): 65-82.

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States (2004) The 9/11 Commission Report: Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States: Executive Summary. US Government Printing Office. Available at: http://bryantassociates.info/ba%20info/_fpclass/amlcft/911_TerrFin_Monograph.pdf. [Accessed 16 February 2021].

National Security Council (2002) The National Security Strategy of the United States of America. Washington, D.C.: Office of the President, September.

O’Neill, W. G. (2002) Beyond the Slogans: How Can the UN Respond to Terrorism. Responding to Terrorism: What Role for the United Nations, pp. 5-17.

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) (2002) Tenth Meeting of the Ministerial Council 6 and 7 December 2002. Available at: https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/b/f/40521.pdf. [Accessed 16 January 2021].

Patrck, S. (2007) Failed States and Global Security: Empirical Questions and Policy Dilemmas. International Studies Review, 9(4): 644-662.

Peceny, M. and Durnan, M. (2006) The FARC’s Best Friend: U.S. Antidrug Policies and the Deepening of Colombia’s Civil War in the 1990s. Latin American Politics and Society, 48(2): 95-116.

Pellerin, M. (2014) Narcoterrorism: Beyond the Myth. Barrios and Koepf eds, op. cit, 22.

Petras, J. (2001) The Geopolitics of Plan Colombia. Monthly Review, 53(1): 30-48.

Pfneisl, M., Kemp, W. and Meduna, M. (2013) A Dangerous Nexus: Crime, Conflict and Terrorism in Failing States. International Peace Institute, 27 November. Available at: https://www.ipinst.org/2013/11/a-dangerous-nexus-crime-conflict-and-terrorism-in-failing-states. [Accessed 17 January 2021].

Piazza, J. A. (2008) Incubators of Terror: Do Failed and Failing States Promote Transnational Terrorism?. International Studies Quarterly, 52(3): 469-488.

Prime Minister’s Strategy Unit (PMSU) (2005) Investing in Prevention: An International Strategy to Manage Risks of Instability and Manage Crisis Response. PMSU: London.

Rahman, M. M. (2019) The US State-building in Afghanistan: An Offshore Balance?. Jadavpur Journal of International Relations, 23(1): 81-104.

Rashid, A. (2010) Taliban: The Power of Militant Islam in Afghanistan and Beyond. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ratner, S. (2002) Jus ad bellum and jus in bello after September 11. American Journal of International Law, 96(4): 905-921.

Reitano, T., Clarke, C. P. and Adal, L. (2017) Examining the Nexus between Organised Crime and Terrorism and its implications for EU Programming. CT Morse Counter-Terrorism Monitoring, Reporting and Support Mechanism. Available at https://icct.nl/app/uploads/2017/04/OC-Terror-Nexus-Final.pdf. [Accessed 3 January 2020].

Richani N. (2002) Systems of Violence: The Political Economy of War and Peace in Colombia. Binghamton: State University of New York Press.

Robertson, N. and Wallace, K. (2001) U.S. Rejects Taliban Offer to Try Bin Laden. CNN, 7 October. Available at: http://edition.cnn.com/2001/US/10/07/ret.us.taliban/. [Accessed 16 February 2021].

Robinson, W. I. (2004) A Theory of Global Capitalism: Production, Class and State in a Transnational World. John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore.

Rochlin, J. (2011) Plan Colombia and the Revolution in Military Affairs: The Demise of the FARC. Review of International Studies, 37: 715-740.

Rosato, S. and Schuessler, J. (2011) A Realist Foreign Policy for the United States. Perspectives on Politics, 9(4): 803–819.

Rosen, J. D. (2014) The Losing War: Plan Colombia and Beyond. Suny Press.

Rotberg, R. (2003) State Failure and State Weakness in a Time of Terror. Brookings Institution Press.

Rotberg, R. I. (2002a) Failed States in a World of Terror. Foreign Affairs: 127-140.

Rotberg, R. I. (2002b) The New Nature of Nation-State Failure. The Washington Quarterly, 25(3): 85-96.

Rowley, J. (2002) Using Case Studies in Research. Management Research News.

Rubin, B. (1995) The Fragmentation of Afghanistan. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Rubin, B. R. (2006) Peace Building and State-Building in Afghanistan: Constructing Sovereignty for Whose Security?. Third World Quarterly, 27(1): 175-185.

Schelenz, L. (2017) Ontological Security-What’s Behind this New Theory Trending in IR?. Universitätsbibliothek Johann Christian Senckenberg. Available at: https://www.sicherheitspolitik-blog.de/2017/08/28/ontological-security-whats-behind-this-new-theory-trending-in-ir/#fn-8869-1. [Accessed 30 March 2021].

Schmid, A. P. (2005) Links Between Terrorism and Drug Trafficking: A Case of Narco-terrorism?. International Summit on Democracy, Terrorism and Security, 27.

Shanty, F. (2011) The Nexus: International Terrorism and Drug Trafficking from Afghanistan. Oxford: Praeger.

Shaw, D and Moore, D. (2020) The Members of Congress Who Profit From War. The American Prospect, 17 January. Available at: https://facethefactsusa.org/facts/fed-contractors-profit-war-terror/. [Accessed 17 April 2021].

Shaw, M. and Mahadevan, P. (2018) When Terrorism and Organized Crime Meet. CSS Policy Perspectives, 6(7). Available at: https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/bitstream/handle/20.500.11850/292077/2/PP6-7_2018.pdf. [Accessed 16 January 2021].

Shifter, M. (1999) Colombia on the Brink: There Goes the Neighborhood. Foreign Affairs, 78: pp.14-20.

Stebbins, S. and Comen, E. (2019) Military Spending: 20 Companies Profiting the Most from War. USA Today, 21 February. Available at: https://eu.usatoday.com/story/money/2019/02/21/military-spending-defense-contractors-profiting-from-war-weapons-sales/39092315/. [Accessed 17 April 2021].

Stokes, D. (2003) Why the End of the Cold War Doesn’t Matter: the US War of Terror in Colombia. Review of International Studies: pp.569-585.

Takeyh, R. and Gvosdev, N. (2002) Do Terrorist Networks Need A Home?, The Washington Quarterly, 25(3): 97-108.

Tarnoff, C. (2010) Afghanistan: US Foreign Assistance. Library of Congress Washington DC Congressional Research Service.

Thachuk, K. L. (2007). Transnational Threats: Smuggling and Trafficking in Arms, Drugs, and Human Life. Westport: Praeger Security International.

The Guardian (2001) Bush Rejects Taliban Offer to Hand Bin Laden Over. 14 October. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/oct/14/afghanistan.terrorism5. [Accessed 16 February 2021].

The United Nations Security Council (2001) Resolution 1368 (12 September 2001) [Online]. S/RES/1368. Available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/448051?ln=en. [Accessed 15 February 2021].

The Washington Post (2001) Text: Bush Announces Strikes Against Taliban. 7 October. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/nation/specials/attacked/transcripts/bushaddress_100801.htm. [Accessed 16 February 2021].

The White House (2004) President Urges Readiness and Patience: by the President, Secretary of State Colin Powell, and Attorney General John Ashcroft, Camp David. Available at: https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2001/09/20010915-4.html. [Accessed 27 January 2021].

Tripathy, J. P. (2013) Secondary Data Analysis: Ethical Issues and Challenges. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 42(12): 1478.

Tsui, C. K. (2015) Framing the Threat of Catastrophic Terrorism: Genealogy, Discourse and President Clinton’s Counterterrorism Approach. International Politics, 52(1): 66-88.