Following the culmination of the Second World War, Keynesian economic orthodoxy characterised western states’ economic policymaking. The latter’s pre-eminence began to falter as neoliberalism replaced it as the new hegemonic model for economic policymaking (Boston, 1987; Hall, 1989). Neoliberal reforms had transformative implications, eliciting significant controversy, particularly for the Thatcher Government between 1979 and 1991 in the United Kingdom (UK) and the New Zealand (NZ) Fourth Labour Government from 1984 to 1990. Both NZ and the UK mirrored each other in their neoliberal macroeconomic policy approaches, except in one key area – social policy (Boston, 1987; Menz, 2002).

Despite neoliberalism’s significant and transformative implications, existing comparative political economy literature could not define and apply the term to reflect an acknowledgement of its nature as heterogeneous, historically contingent, and susceptible to change over time (Ban, 2018; Ban, 2016). Studies focusing on the comparative impact of the neoliberal policy model between two or more states fail to recognise the significance, nature, and role of ideational processes surrounding neoliberal ideology and how such processes impact state-level policymaking behaviour (Ban, 2018).

If NZ and the UK are comparatively analysed, studies show what made the two similar based on outcomes. Whereas accounts for why they differed in specific instances are absent. One policy area of difference between both was in social policy, and, with only partial and limited explanations currently available, this research addresses this variance in approaches to social policy.

I argue that a policy transfer and ideational approach are required to address this question substantively. Studies that analyse each country during this period have often overlooked the critical impact and role of ideas on policymaking. Framing my analysis reveals the influential role ideas had on domestic policymakers in both UK and NZ and how the ideational processes behind UK policymaking behaviour spread transnationally and, in turn, influenced NZ policymakers.

Literature Review

Current Approaches in Cross-Country Policy Research

Policy transfer or policy diffusion are the two approaches explaining cross-country policy formulation and implementation (Marsh & Sharman, 2009; Meseguer & Gilardi, 2009). Policy transfer is a “process by which policies, administrative arrangements, institutions … in one political setting” lead to the facilitation and development of “policies … institutions … in another [setting]” (Dolowitz & Marsh, 2000, p. 3-5), while policy diffusion is the “process through which policy choices in one country affect those made in a second country” (Marsh & Sharman, 2009, p. 270; Braun & Gilardi, 2006; Obinger et al., 2013). Marsh and Sharman (2009) conclude that, while policy transfer theory focuses on agency, diffusion studies emphasise structure (p. 269, 274-275, 285). However, policy diffusion “does not imply a world without agency”, and both agency and structure are significant in each approach (Lee & Strang, 2006, p. 883; Newmark, 2002). Under a rationalist paradigm, as in much diffusion literature, policymakers “scan the international environment in search of policies that have worked well elsewhere; … through a … cost-benefit analysis” and select a policy that “can contribute to maximising its utility in the country in question” (Verger, 2016, p. 108; Meseguer, 2006).

Nevertheless, diffusion studies focus on policy outcomes instead of causal accounts explaining policy outcomes and assume that “economic policies can be deployed independently of the economic ideas from which they stem” (Ban, 2018, p. 51). This current study focuses on causal analysis of the spread of neoliberal policy ideas to account for the variation in social policy approaches in two different contexts. For this reason, the policy diffusion framework is not adequate for addressing the research aims. In contrast, while transfer literature is limited in accounting for why transfer occurs “in particular settings and not others”, it remains relevant for this analysis due to developments in the constructivist political economy (Benson & Jordan, 2011, p. 370).

Constructivist political economy is complementary to the aims of policy transfer research. Transfer literature emphasises the effect of actors on the transfer process (Marsh & Sharman, 2009, p. 279; Stone, 2001, p. 2; Knill, 2005; Monios, 2017, p. 352); alternatively, constructivist political economy conceives “actors [as] a-rational,” because their actions do not reflect a “utility maximiser with clear goals” (Carstensen, 2011b, p. 602; Carstensen, 2011a; Schmidt, 2008a). In this discourse, actors are pragmatic; constrained by their interpretive filters, they incrementally combine elements of “existing ideational and institutional” legacies in “the form of a bricolage,” eventually “leading to significant political transformation” (Carstensen, 2011a, p. 148; Carstensen, 2011b). In this way, “actors and ideas are interrelated” (Carstensen, 2011b, p. 602; Bevir & Rhodes, 2003, p. 35–37; Parsons, 2007: 98). This depiction of agency and ideational processes complements transfer literature, given its focus on how, and in what context, endogenous factors in “the recipient state” affect the influence and potential implementation of exogenous policy ideas on that state’s “domestic policymaking” (Marsh & Sharman, 2009, p. 279; Lenschow et al., 2005). Additionally, this perspective corresponds with the above definition of neoliberalism as a historically contingent process, whereby ideas and economic theory overlap, thus influencing policy decision-making in different contexts (James & Lodge, 2003; Lenschow et al., 2005; Marsh & Sharman, 2009, p. 279). Accordingly, a transfer and constructivist political economy perspective enable a reconceptualisation of agency and its relationship with ideational factors. More importantly, this framework facilitates this study’s ability to account for the differences in social policy approaches in the UK and NZ between 1984 and 1990 and, therefore, can demonstrate the impact of ideas on policymaking behaviour.

Neoliberal Reforms in NZ and the UK

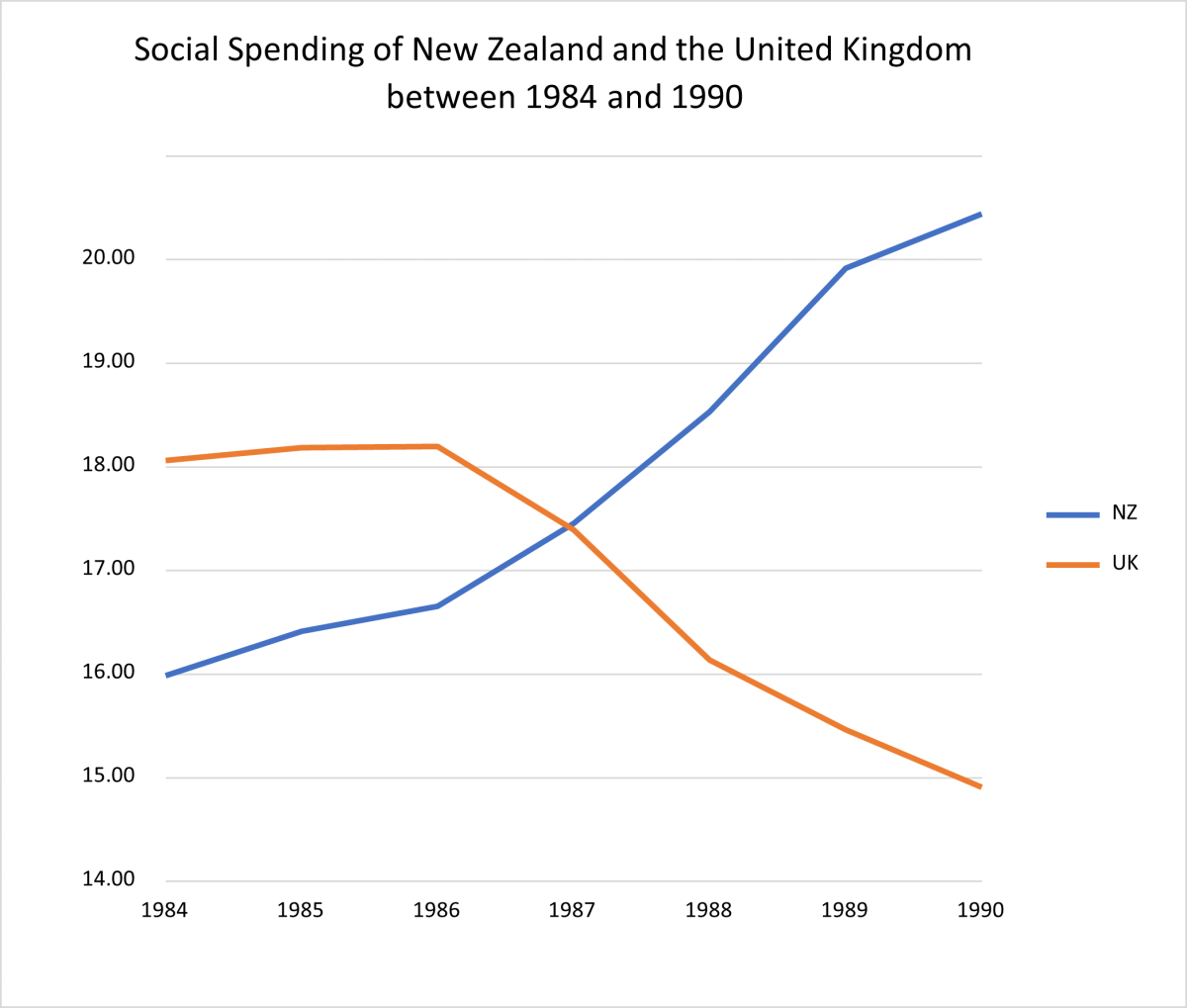

The UK and NZ were early adopters of the neoliberal paradigm shift. While in the UK, a Conservative Government initiated radical reforms for their time, in NZ, the neoliberal ‘revolution’, led by a social-democratic Labour Government, was perceived as ‘paradoxical’. This was not simply a consequence of the nature of the reform but of which political party had executed it (Boston, 1987, p. 129). For instance, reforms in monetary, fiscal, and public sector policy in both NZ and the UK mirrored each other, but this was not the case for their chosen social policy approach. Boston (1987) found the UK Conservative Government favoured a “reduction in state-funded welfare services”, which broadly aligns with a neoliberal economic approach, whilst in the NZ case, the welfare state was maintained through targeted assistance to “especially low-income families” (Boston, 1987, p. 133). NZ implemented wide-ranging neoliberal policy reforms comparable to the “structural adjustment programmes commonly advocated by the IMF for developing countries” (Menz., 2002, p. 137). Moreover, OECD data from this period shows that social spending rose significantly for NZ as a percentage of GDP but declined for the UK (OECD, 2021).

Comparative studies of both countries’ approaches to economic reform between 1984 and 1990 have emphasised financial and fiscal deregulation, reductions in corporate tax rates, elimination of subsidies, and other forms of state assistance to sector groups. In these particular areas, the two governments pursued broadly similar agendas. If a social policy is mentioned, it is only in broad terms as an adjunct to the more comprehensive macroeconomic reforms underway (Boston, 1987, p. 130; Menz, 2002; Menz, 2005). Boston’s (1987) comparative analysis of both countries follows this approach and suggests that the difference in social policy approaches between the UK and NZ is significant (p. 150). Nevertheless, he does not offer a causal explanation as to why the variance occurred. Therefore, his findings cannot substantiate the reason for this specific policy difference between the UK and NZ (Boston, 1987). Causal inferences are required to confirm Boston’s conclusion that the “defence of the welfare state … distinguishes the domestic policies of the NZ Labour Government from … the British Conservative Government” (Boston, 1987, p. 150). This study addresses this gap in accounting for why social policy variation occurred in NZ and the UK from 1984 to 1990.

Menz (2002) employs a policy transfer analysis to illustrate the significance of ideas as causal influencers of policymaking in NZ and portrays policymakers as rational actors highlighting the similarities between NZ and the UK regarding policy reforms (Menz, 2002, p. 137). As with Boston’s analysis, Menz’s study focuses on similarities between the two approaches rather than differences and cannot persuasively explain the variance in social policy between the UK and NZ.

In his article, Carstensen (2011b) uses a constructivist perspective to consider the evolution of UK policy implementation from one that emphasised the state’s role to one that focused on the individual. This perspective ultimately shifted the paradigm from the view that the state had a pivotal role in supporting the unemployed through welfare policy to one that emphasised individual agency and reductions in benefits, together with fewer incentives for the betterment of domestic social conditions (Ibid). Despite this policy representing a sharp contrast to and being “in opposition to Old Labour policies”, it was continued by the Blair Government (Ibid,

p. 607). Carstensen notes how Conservative policies based on “human capital/empowerment and individual incentives” were extended by reinstalling a measure of “responsibility on the part of the state” (Ibid, p. 607-608). This strategy enabled Labour to “draw in Labour votes” and voters from the conservative base as part of “Labour’s effort to position the party at the centre of British politics” (Ibid). This entire process reflects an incremental ideational change as Labour extended the “conception of individualisation… already in place under the Conservative Government”, incrementally enabling them to “capture the … middle ground” for electoral success (Ibid). This illustrates the capacity for policy agents to produce policy bricolage – hybrid policy consisting of multiple sources of policy ideas – in both a meaningful and pragmatically evolving way to serve political interests without radically disrupting the existing status quo.

Conceptualising actors as bricoleurs and utilising a constructivist perspective framed by a policy transfer approach helps explain why social policy differed between NZ and the UK from 1984 to 1990, despite both governments pursuing neoliberal economic policies. This approach contributes to our current understanding of the significance and role ideas have in accounting for cross-national policy differences.

The Policy Paradox Puzzle

The existing literature has identified a ‘social policy paradox’ concerning the variance in social policy approaches between NZ and the UK during their respective neoliberal reform processes from 1984 to 1990. I argue that accounting for this variance requires considering the global spread of policy ideas and the effect on both countries’ domestic structure and agency. I claim policy transfer is a better explanatory approach than policy diffusion accounting for cross-country policy variations. Policy diffusion analysis concentrates on outcomes when explaining cross-national policy trends or divergence. Nevertheless, the outcome of social policy variation between both countries remains causally unaccounted for by the literature, and subsequently, a diffusion approach is judged inapplicable for this study.

Policy transfer remains applicable to this analysis because of its emphasis on the role of ideas and their impact on endogenous policy decision-making. Constructivist political economy complements this focus as it reconceptualises policy agents as bricoleurs, combining pre-existing policy ideas with more novel approaches pragmatically and incrementally (Carstensen, 2011a; Carstensen 2011b). Framing this study through a policy transfer approach from a constructivist perspective offers a more enriching analysis that can account for the social policy variation between countries. I thereby designate NZ policymakers – and their UK counterparts – as active engagers of transnational policy ideas, however pragmatic in their methods.

Applying these two approaches will help demonstrate the dynamic inter-relationship between agency and exogenous ideational processes at a micro-level. (Risse-Kappen, 1994; Acharya, 2004; Ban, 2018). Using Carstensen’s theory can also highlight how transnationally disseminated ideas change, reinforcing the applied theoretical framework and definition of ideas (Carstensen, 2011b; Ban, 2018, p. 56-57; Latour, 1987, p. 132). By merging soft policy transfer with Carstensen’s theory of incremental ideational change, the following can illustrate the dynamic and interactive relationship between ideational processes and agency behaviour regarding policymaking, further demonstrating the significance of ideas within comparative policy research to account for the cross-national social policy variance between NZ and the UK.

Definition of Terms and Applied Theoretical Framework

Ideas, Welfare, Social Security and Neoliberalism

To account for differences in social policy between the UK and NZ and to demonstrate the significance of ideational processes on policymaking behaviour, the terms ideas, welfare, and social security requires conceptual clarity. Ideas are defined as “web[s] of related elements of meaning” and refer specifically to policy ideas within subsequent analysis (Carstensen, 2011b,

p. 600). Analysing the relation between an idea’s internal elements provides a clearer understanding of the overall meaning of the idea itself (Ibid., p. 601). Elements of meaning refer to the socially constructed “cognitive shortcuts” policy agents use to “reduce societal complexity” when addressing policy issues (Ibid). Cognitive shortcuts provide agents with heightened clarity and simplicity from which they may act, hence framing their understanding of what an idea means (Ibid.). Although the internal elements of an idea are pertinent to ascertaining a clearer understanding of an idea’s meaning, ideas “are not closed systems of fixed meaning”; they too are subject to change per the impact of their surrounding environment (Ibid., 602).

Welfare is defined as “the goals of social security systems and measures of the performance of systems, schemes or programmes” (Walker, 2005, p. 7- 8). I define social security in a general sense to “include social insurance benefits; non-contributory cash benefits” and “means-tested benefits” (Ibid., p. 5-6). The latter refers to policy schemes where individuals “can claim if their income” is below a “prescribed standard”. Non-contributory benefits refer to provisions aimed at claimants with disabilities “irrespective of their resources” (Ibid.).

Despite the term being prevalent within existing scholarship, there is no single definition of neoliberalism (Boas & Gans-Morse, 2009; Ban, 2018; Ban, 2016). While many define the term, others use it in a more general way, acknowledging that there may be inconsistencies within the broader meaning of the term (Ban, 2016; Bourdieu, 1998; Block & Somers, 2014; Boas & Gans-Morse, 2009; Mirowski, 2013). Scholars “frequently fail to define the term” (Boas & Gans-Morse, 2009, p. 144). In this way, neoliberalism has become something of a ‘broad church’, meaning anything associated with capitalism more generally, underpinned by an adherence to monetarism and deregulation (Boas & Gans-Morse, 2009). Compounding this definitional challenge are views from ideational scholarship, which point to the discursive transformation of ideas that determine the specific neoliberal typologies that policymakers use as reference points (Carstensen, 2011a; Schmidt, 2017; Ban, 2016). With these considerations in mind, I utilise the following definition, which characterises neoliberalism as: “[a] set of historically contingent and intellectually hybrid economic ideas derived from … economic theories whose goals are making economic policies credible with financial markets and ensuring trade and financial openness.” (Ban, 2016, p. 11)

Here, I acknowledge neoliberalism’s heterogeneous nature by noting how ideas generally, economic theory more specifically, and historical context, collectively overlap, inform, and influence monetary policy decisions. Defining neoliberalism in this manner corroborates how I consider ideas as not necessarily “coherent or stable entities” but from their “multi-interpretability” by policy agents who engage and refer to it in their policymaking (Carstensen, 2002, p. 602; Schmidt, 2017; Smidt & Thatcher, 2013). Previous literature failed to define it without considering its ideational tenets, which this definition achieves.

Applied Framework

The applied framework will help analyse the social policy variance between NZ and the UK by merging developments in the current constructivist political economy and policy transfer scholarship. Policy transfer refers specifically to the “process by which knowledge of policies, … and ideas in one political system (past or present) are used in the development of similar features in another” (Dolowitz, 2000, p. 3; Benson & Jordan, 2001). Transfer prioritises the role of ideas and how these can affect endogenous agency behaviour regarding policy decision-making. This study defines agents as “elected officials; political parties; bureaucrats/civil servants; pressure groups; policy entrepreneurs/experts; and supra-national institutions” (Dolowitz & Marsh, 1996, p. 345). Typically transfer comprises either “hard” or “soft” transfer. Hard policy transfer refers to “policy instruments, institutions and programmes between governments”, while soft policy transfer – the specific type of policy transfer I subsequently consider – refers to the transfer of “ideas, ideologies and concepts” (Dolowitz & Marsh, 1996, p. 349-350; 2003; Benson & Jordan, 2001 p. 370; Stone, 2004).

Carstensen’s theory of incremental ideational change (2011a; 2011b) completes the theoretical framework needed to analytically focus on the relationship between ideas and policy agents and ideational processes. Carstensen posits that ideas constantly undergo incremental ideational change, even in times of stability (Carstensen, 2011b, p. 596). Ideas change when the relationship between their existing elements changes or when “one but not all elements of an idea” are modified (Carstensen, 2011b, p. 596). Alternative ideational theories demonstrate the importance of ideas as drivers behind the institutional change, but they assume that ideas only change during crisis periods (Ibid.). This assumes that ideas are more stable than they are open to change and that the nature of ideational change is immediate instead of incremental. Instead, an idea’s meaning is determined by its web of related elements of meaning which, Carstensen argues, are constantly subject to “potential changes”, not solely during periods of crisis (Ibid., p. 602).

According to Carstensen, understanding how ideas undergo incremental change involves reconceptualising policy agents as bricoleurs, non-rational actors who use cognitive shortcuts to combine and recombine pre-existing policy ideas with novel approaches to determine their behaviour (Carstensen, 2011a, p. 163-164). However, this theory argues that ideas are not necessarily “internalised” by agents, given their cognitive limitations and dependency on cognitive shortcuts (Ibid p. 164). Agents hence play a role in the extent of influence and significance that ideas have on meaning and play a crucial role in how ideas change over time.

Having demonstrated how the agency is conceptualised, it becomes possible to effectively demonstrate in subsequent analysis the agency’s important role in an idea’s influence and propensity to change, specifically in an incremental manner. Thus, understanding agents as bricoleurs and how they engage with ideational processes further the theoretical application of incremental ideational change theory to discern better how “ideas change” (Carstensen, 2011a, p. 164).

Carstensen’s work fits within the context of a policy transfer approach because it focuses on the specific interactions between agencies – specifically NZ and UK policymakers – and ideational processes, either endogenous or exogenous, regarding domestic policymaking. Applying this theoretical framework further emphasises the interaction between agency and ideas to better account for why UK and NZ policy agents differed in their approaches to social policy (Risse-Kappen, 1994; Acharya, 2004; Ban, 2018).

Policy transfer, however, remains applicable to this analysis because of the emphasis it places on the role of ideas and their impact on endogenous policy decision-making. Constructivist political economy complements this focus as it reconceptualises policy agents as bricoleurs (Carstensen, 2011a; Carstensen, 2011b). Framing this study through a policy transfer approach from a constructivist perspective offers a more enriching analysis that can account for the social policy variation between countries. Nevertheless, this study designates NZ policymakers – and their UK counterparts – as active engagers of transnational policy ideas, however pragmatic in their methods. (Ban; 2016; Menz, 2002; Braun & Gilardi, 2006).

Methodology

Research Design

The comparative-historical research (CHR) method is applied to frame this study’s research design. CHR compares and contrasts two or more units’ “overtime” to understand social processes, reinforcing my research aims (Mahoney, 2004, p. 81). NZ and the UK act as the comparative units of analysis over the 1984-1990 period. An analysis of both during this period will determine why social policy differed and demonstrate the value and impact of ideational processes on domestic policymaking.

CHR provides a holistic perspective that emphasises both context and conditions that can elicit causal accounts behind interactions between social phenomena and units of analysis. CHR also lends itself to a cross-sectional analysis through which the “large-scale” implications of given phenomena can be discerned. Therefore, this approach offers conceptual clarification of simultaneous causes that may account for specific phenomena (Larner & Walters, 2000; Collier, 2011). Following existing literature, this study frames the emergence of neoliberal policy reform as a socio-political event that had radical contemporary implications for both NZ and the UK (Boston, 1987).

Sampling, Case-Selection and Research Questions

Given the qualitative nature of this inquiry, purposive, non-probability sampling is employed with the theoretical framework outlined above. Qualitative research has many advantages for analysis since it can enrich the current understanding of selected case studies. It avoids generalising these findings – a common feature of quantitative research (Ishak & Abu Bakar, 2014; Neuman, 2009).

In CHR, the process of case study analysis is inductive and empirically driven, reinforcing the purposive sampling process. In this way, the “selection of participants can be conducted non-random” to “select unique” and relevant cases that identify themselves as “cases for in-depth investigation” (Ishak & Abu Bakar, 2014, p. 32). NZ and the UK are the two cases selected for this study because they complied with the Most Similar Systems Design (MSSD). Under an MSSD approach, cases that are more similar than different are comparatively analysed according to a distinguishing feature to establish causality (Anckar, 2008, p. 393). Purposive sampling enabled me to extrapolate similarities between countries. During the 1984-1990 period, similarities included a shared language; strong Westminster Parliamentary traditions; a First-Past-the-Post electoral system; an executive arm exercised through the executive powers of the respective cabinets; and their shared status as constitutional monarchies (Docherty & Seidle, 2003; Boston, 1987; Larner & Walters, 2000; Levine & Roberts, 1994). The distinguishing feature between both cases was social policy, given that, in almost every other policy area, the neoliberal reform agenda’s implementation was overwhelmingly similar (Menz, 2005; Menz, 2002; Boston, 1987; OECD, 2021). Together, these factors explain the utility of the MSSD approach.

The operationalisation of social policy approaches is the other aspect of this study. I refer to the UK Social Security Act of 1986 (SSA) and the NZ Royal Commission on Social Policy of 1988 (RCSA) to represent each government’s perspective and approach to social policy. It is noted that alternative iterations of UK and NZ social policy did exist during this period. These will be referred to in passing because it is argued that both the SSA and the RCSP reflected the culmination of these earlier – and less extensive – iterations of the NZ and UK Government’s approaches to social policy. Operationalising social policy approaches on these terms clarifies and widens this study’s analytical scope and focus to account for social policy variance between NZ and the UK.

Research evidence is derived from secondary sources (Mahoney, 2004). These include the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) database to illustrate the variation in social spending between the UK and NZ (OECD, 2021). This is combined with a review of the historical and political economy literature from and about the period under consideration (Evans, 2019; Pierson, 1997; Layard & Nickell, 1989; Reitan, 2003; Menz, 2005). While secondary sources are a potential limitation of this study, access to primary sources is hampered because many of the key individuals who worked during this period are deceased. In addition, archival material is limited and not yet online and was inaccessible due to COVID-19.

Utilising available secondary sources to address the following research questions, as informed by this study’s central aims are labelled below.

- How can we account for variance in social policy approaches in NZ and the UK between 1984 and 1990?

- How significant are ideas regarding cross-national policy research?

Analysis and Discussion

Accounting for Variance in Social Policy Approaches in NZ and the UK between 1984-1990

During this period, both NZ and the UK implemented sweeping reforms to mitigate rising inflation, manage rising wages, reduce costs, and improve economic efficiency and productivity. Both governments operated under the assumptions that the cause of inflation was due to “excessive growth of money supply” and that “supply-side” measures were necessary to remedy this. These included encouraging work incentives by reducing income tax rates, the deregulation of financial and labour markets, and reforms to the public sector to make it more efficient (Boston, 1987, p. 132).

These policies drastically broke from economic orthodoxy and interventions that had characterised the previous decade. In the UK, the government argued that these policies were necessary because, among other things, there was an “excessive level of welfare expenditure, high marginal tax rates … slow adjustments of wages” (Ibid., p. 134). The NZ Fourth Labour Government characterised its reforms as ones that sought to undo the consequences of the previous government’s “excessive interventionism” and “inappropriate state-led investment strategies”. More broadly, both governments argued that Keynesian economic policies “could not reduce unemployment”; thus, an “alternative approach” was “necessary” (Ibid., p. 135). While both countries enacted neoliberal policy, social policy remained a key area of difference.

Unlike the UK, which favoured “a reduction in state-funded welfare services and privatisation of provision where feasible”, the NZ Labour Government intended to “maintain” the “welfare state” by directing assistance toward “low-income families” (Ibid., p. 133). Figure 1 helps illustrate this social policy divergence regarding social spending as a percentage of GDP.

Accounting for social policy differences between NZ and the UK requires focusing on causal factors. Such a focus prioritises the significance of ideas – specifically policy ideas – and their dynamic with policy agents across different domestic contexts and how this influenced domestic policymaking. Regarding the SSA in the UK and the RCSP in NZ, this paper’s conception of agents as bricoleurs demonstrates the impact of ideational processes on policymaking and the transformative role of agency when engaging with said processes which lead to policy change over time.

UK’s welfare reform’s primary focus, rooted in the neoliberal policy reform, was to alter the structure and funding of social security. In fact, ‘the development of the conditional and affordable welfare state’ was a clear “policy goal” of the UK Government (Albertson & Stepney, 2020, p. 325; Stepney, 2018a, p. 45). The UK reforms resulted in a reversal of the “governments’ commitment to universal social security; it would instead “provide” benefits based on means-testing” (Mabett, 2013, p. 43). Social security had, up until this point, “been the major feature of state welfare” and the “largest item of state expenditure” (Alcock, 1990, p. 89). There was also a perception that the state was a “massive bureaucracy”, which explained the increasing levels of state expenditure, and that it was this bureaucracy that needed reform and consolidation (Mabett, 2013, p. 43). The UK Government agreed with this perception arguing that “everything that could be privatised would be privatised”, significantly diminishing the state’s role in “securing the population’s living standards” (Alcock, 1990, p. 89).

The UK Government’s strategy for social security reform underwent continuous evolution before it culminated in the Social Security Act of 1986. Even after the earlier iterations of Social Security Acts I and II, their “ideological strategy … was not clear”, though their fundamental objective, driven by a neoliberal conceptualisation of the economy, of a smaller state remained. Above all, it implied a revised conception of the “collective responsibility of the state” in providing welfare support (Alcock, 1990, p. 92-98). There were several instances, for example, where the government’s strategy was merely a consequence of path dependency, in that it was simply continuing policy directions in line with existing ideational discourse and practice as had been the case under the previous Labour Government (Boston, 1993; Dominelli, 1988). This is especially evident when analysing the role of the Fowler Review in “shifting the discourse on the welfare state in favour of “neoliberal perceptions, which advocated for its retrenchment and “the individual from’ welfare dependency” (Dominelli, 1988, p. 49).

Nevertheless, this falsely implies that ideas on welfare claimants turned adverse only after the Fowler Review had occurred. In fact, “the ideological aversion to the welfare scrounger had become a widespread phenomenon before the Thatcher Government [took] power” (Golding & Middleton, 1982; Alcock, 1990, p. 98). The review actually “built upon … the Social Security Review of 1976,” which the Labour government had initiated “to redistribute benefits amongst existing claimants to target the more needy” because: “…[too] many people were claiming benefits when they were not entitled to do so”. (Dominelli, 1988, p. 49-50)

This approach to the welfare state corresponded with the neoliberal approach, both in general and reducing social welfare recipients and associated costs. Indeed, what policymakers in the Conservative Government achieved was too ubiquitous the negative connotation of “welfare dependency” associated with excessive spending. This was, at its heart, an ideational strategy to negatively depict the welfare state as detrimental to class mobility (Dominelli, 1988). Instead, the government now encouraged claimants “to take up employment opportunities” to make them “free beings” liberated from the constraints of a welfare system that had “controlled their lives” and affected “their right to independence and choice” (Ibid., p. 50). In this regard, it is not difficult to see Carstensen’s fundamental observation at work: “agents use ideas creatively in the effort to secure their interests” and form a bricolage of novel and existing policy ideas to institute policy change (Carstensen, 2011a, p. 600; Carstensen, 2011b). Government policymaking benefitted from applying the welfare dependency concept as an “ideological construct” to further their interests in enacting what they viewed as long overdue social security reform (Dominelli, 1988, p. 50). This example reflects the dynamic relationship between both agents and ideas. While the idea of benefit exploitation did exist before their electoral victory in 1979, the new government’s neoliberal perspective could extend this. This allowed it to frame the welfare state itself as a problem and focus on the perceived high levels of public expenditure on social security and the need for the government to reduce this substantially.

Additionally, the proposals of the ASI, which the government implemented to a great extent in 1986, reflect the role of ideas shaping policy approaches, thereby reflecting the heterogenous application and meaning of neoliberalism. Alcock argues that the government’s implementation of the measures contained in the ASI proposal “was not only financially wasteful” given that they “extended the boundaries of state support unnecessarily” via the deregulation of existing regulatory frameworks to deliver provisions to those “in proven need [but] they also contradict the principles of private self-protection” (Alcock, 1990, p. 102). Indeed, while the 1986 legislation aimed to reduce social security spending significantly, a report on the legislation showed that, despite a 6% reduction in means-tested benefits spending, social security spending remained the same (at 29%) throughout both the periods 1986 to 1987 and 1990 to 1991 (Evans et al., 1994, p. 2-3).

Under the pretext of driving neoliberal grounded “claims about the undesirability of the all-extensive state,” the government’s failure to effectively reduce growing social security expenditure represents a significant contradiction in its neoliberal social policy approach (Alcock, 1990, p. 103-104). This reflects the heterogeneous and pliable nature of neoliberalism. The ability to shape the overall concept of neoliberalism in policy application acted as a critical enabler of the reform process, with UK Government officials dynamically engaging with exogenous ideas emerging from institutions, such as the ASI. These novel ideas were merged with pre-existing approaches from the previous Labour Government and were creatively exploited and manipulated to enhance their reforming of the welfare state. This demonstrates the dynamics and significance of the interrelationship between agency and ideas when influencing and implementing policy change.

Standing in sharp contrast to the UK experience with the social policy applied within a neoliberal framework is the case of NZ over the same period, notwithstanding a similarly strong broader neoliberal focus on macroeconomic reform.

Substantial evidence exists of policy transfer influence from the UK to NZ. Ideas, concepts, and experiences ‘travelled’ between the two countries via specific channels of influence. Menz writes how two key channels – US education/professional work experience and the UK’s historical and cultural influence – enabled neoliberal policy ideas to disseminate and enter the NZ policymaking arena (Menz, 2002). Several treasury officials “either received their graduate degrees in the US, had been sponsored by the Treasury to do so …, or had spent time at US-based … institutions [like] … the IMF” (Ibid., p. 147). Examples include the eventual deputy governor of the NZ Reserve Bank Rod Deane, who worked previously at the World Bank (Ibid).

Additionally, two Treasury officials who had co-authored the government’s manual for neoliberal reforms “had spent stints at Harvard” while the other “had … received additional training at Harvard Business School … before serving as Secretary to the Treasury between 1986 and 1993” (Kelsey, 1997, p. 47-54, 154; Menz, 2002, p. 146). Additionally, the neoliberal influence of the UK, which had begun reforms five years earlier, seemed to have influenced NZ officials. NZ Treasury officials frequently referred to the desirability of the neoliberal model as one NZ urgently required, given its contemporary economic situation (Menz, 2002, p. 146; Kelsey, 1997).

The UK’s historical and intellectual legacy also impacted NZ policymaking. NZ, at the time, operated under “a Westminster-style ‘first-past-the-post’ political system, composed of a one-chamber parliament and only two major political parties” (Menz, 2002). Thus, when Labour won the 1984 election, “it commanded [an] absolute majority of seats”, leaving opposition parties with little ability to challenge its policymaking (Ibid). In social policy, however, the influence of these neoliberal policy ideas failed to materialise. This difference is typically attributed to the pre-existing ideational and identity norms within the Labour Party, which comprised a progressive identity toward the NZ welfare state. More specifically, however, it reflected the active engagement of the NZ agency in changing the elements of meaning behind these transnationally disseminated neoliberal policy ideas to preserve and expand social policy, not reduce it, despite neoliberal policy ideas favouring social policy retrenchment.

Despite facing similar economic challenges as the UK in the mid-1980s and pursuing broadly similar macro-economic reforms aligned with neoliberalism, the NZ Labour Government took the opposite direction regarding social security provisions. Upon assuming office, the government enacted several reforms to improve welfare provisions for its citizens. For instance, in 1984, family benefits were increased to support working-class families. Additionally, the threshold for public benefits was improved to provide more assistance to claimants when seeking employment (Evans et al., 1994; Schwartz, 2000; Angresano, 2007). Moreover, 1985 saw the passing of the Tax Reform Package. This lowered tax rates for the working and middle class (Easton, 1997; McCluskey, 2008). In that same year, the government’s budget significantly increased benefit rates by up to 80% for disability claimants and introduced the Special Accommodation Benefit to assist working-class tenants (McTaggart, 2005).

In 1986, the government reformed its social security programme to enable more significant financial support to families working full-time with dependent children (Angresano, 2007, p. 109) – the antithesis of the UK model in precisely the same year. These changes, while numerous, acted as a prelude to the Royal Commission on Social Policy (RCSP) in 1988. The objective was to reinforce the Labour Party’s historical commitment to its social democratic values and norms of supporting the NZ welfare state (Easton, 1997; Boston, 1993; Barnes & Harris, 2011), a point confirmed in a subsequent assessment by the then Prime Minister, Rt Honourable David Lange (Lange, 2005). It also, however, demonstrated bricoleur behaviour on the part of NZ policy agents. This is because while almost every other economic policy area mirrored the reforms of the UK, NZ policymakers combined these novel neoliberal policy prescriptions with pre-existing policy ideas – in this case, social policy. This, in essence, changed the elements of meaning of what neoliberal policy models allowed for in the NZ context; that is, preservation of pre-existing social policy norms. The government established the RCSP in 1986, and, within two years, its findings were published.

The RCSP’s intentions were a long way from neoliberal perceptions of the state’s role. It claimed that the role of the government was “to ensure that all citizens, irrespective of their socio-economic backgrounds,” were provided with enough support for community participation and financial dignity (Barnes & Harris, 2011; Boston, 1993, p. 65). Several studies argue that this was an apparent attempt by the Labour Government to retain its social democratic identity and defend the social policy from neoliberal policy reformers, including in a bid to avoid a similar social policy direction as observed in the UK during this same period (Barnes & Harris, 2011, p. 2; Easton, 1997; O’Brien, 2008). The RCSP “broadened the scope of what could be considered social policy”, yet it provoked controversy during its unveiling. It ran headfirst into neoliberal preoccupations regarding social policy (Barnes & Harris, 2011, p. 4; McClure, 1998, pp. 227-228). The NZ Treasury took a strongly negative view of the RCSP, believing it reflected an attempt by the government to expand social policy expenditure in contradiction to its broader economic reforms.

Effectively, the RCSP was part of the Labour Government’s strategy of retaining its social democratic focus by maintaining the welfare state, even if all around it, fundamental neoliberal reforms were in motion. Notably, the build-up to the RCSP resulted from the incremental change that saw various progressive social policy reforms implemented in direct contradiction to the NZ Treasury’s neoliberal reform agenda. Their officials’ education was influenced by the US and UK Treasury, with both countries remaining highly influential to NZ’s “intellectual climate [and] culture” and had also already implemented neoliberal ideas into the policy (Menz, 2002, p. 144). This transfer of neoliberal policy ideas from the UK to NZ accounts for the NZ neoliberal reform experience. However, it cannot explain why the neoliberal agenda, so vigorously pursued across the NZ economy, did not transpire in social policy.

This variance can be explained by the success of internal NZ bricoleurs in resisting the transfer of exogenous neoliberal ideational change opposing social policy expansion, instead choosing to change elements of neoliberal policy ideas to retain a socially democratic emphasis on upholding social welfare through state-driven social policy. The ideational foundations for the RCSP in the Fourth Labour Government were already in place due to the earlier work undertaken in the early 1970s by the short-lived Third Labour Government (1972-1975/6). Therefore, the NZ Government enacted social policy reforms resulting from the incremental ideational change that significantly contrasted with the broader neoliberal policy reforms.

The Analytical Significance of Ideas in Cross-National Policy Research

The significant role of ideas in cross-national policy implementation depends on analyses highlighting agents’ conceptualisation as bricoleurs, hybridising existing and novel policy ideas incrementally to reflect the significance and dynamic relationship ideational processes have with the agency. The above analysis, which accounted for the social policy variance between NZ and the UK, demonstrated the transformative potential of agents “hold in processes of ideational … change” (Carstensen, 2011a, p. 148). In the UK, social policy occurred incrementally with the gradual ideational implementation of social policy reforms culminating in the 1986 Social Security Act. UK policy agents acted like bricoleurs recombining “elements from the existing repertoire of ideas to create new meaning.” (Carstensen, 2011b, p. 604). Specifically, the preceding Labour Government had already initiated an ideational path-dependency as its Social Security Review in 1976 had already developed a shift in ideational perception of claimants of welfare benefits. This process was extended and significantly transformed by the Conservative Government policy agents who, over eight years, incrementally developed a “new meaning” of the welfare state as being a scourge of state expenditure and encouraged its citizens instead to rely on private forms of social security to lessen the alleged economic strain progressive social policy caused (Ibid). Notably, policy agents deferred to private agents from specific institutions, particularly the ASI, to continue developing their bricolage, demonstrably reflected by the Social Security Act in 1986.

Policy agents do not operate with a “predefined end-goal” in mind but also do not work “irrationally” because the relationship with ideas is a pragmatic and incremental one (Carstensen, 2011a, p. 155). While the UK Government’s objective was to substantially decrease social security expenditure to align itself with its neoliberal view of reducing the state’s role, achieving this was a dynamic relationship between ideational processes and agency. The significance of UK policymaking ideas was a consequence of the role of policy agents, as novel and pre-existing ideas formed a bricolage that agents used to substantiate their policymaking incrementally.

As discussed earlier, the specific avenues of ideational influence regarding NZ in cross-national policymaking during this period were (a) the educational and professional experience garnered from the US and (b) the existing cultural and colonial legacy of the UK (Kelsey, 1997; Menz, 2002). Many other NZ Treasury officials had worked in or been seconded to the UK Treasury in the NZ General Election in 1984 (Kelsey, 1997). Therefore, they were exposed to and engaged with the UK’s neoliberal programme of reform that had gathered momentum in London since the late 1970s. The Government’s Minister of Finance prepared two documents early in the Fourth Labour Government’s term along with the Treasury. These reflected a “heavy indebtedness” to neoliberal belief in the “superiority of the market” and provided the intellectual framework for NZ’s neoliberal reforms during this period (Goldfinch & Rober, 1993; Easton, 1988; Boston, 1991; Menz, 2002).

Furthermore, the UK’s influence on NZ policymaking was evident in NZ’s electoral system, which ensured the Labour Government governed with a majority. This also served as a precise reference point for enacting neoliberal reforms because the UK had achieved this five years earlier (Menz, 2002). These two factors enabled the NZ treasury to speedily translate these exogenous ideas to the domestic context in rapid, unimpeded succession (Douglas, 1993, p. 67; Menz, 2002, p. 148; Easton, 1994, p. 215).

The NZ Treasury interpreted ideas, disseminated from these channels of influence, to implement their neoliberal policy reforms. However, as previously observed, the adaptation of neoliberal policy ideas exogenously originating from the UK and, to a lesser extent, the US was not applied in social policy. The NZ Government intended to salvage its social democratic identity by reinforcing the role of the welfare state because of the transformative neoliberal policies it had enacted elsewhere.

This argument may not cohere with a rationalist interest theory perspective. Rational choice arguments for why social policy varied would argue that the attempt to reform changes to NZ social policy maximised their electoral support (Strom, 1990, p. 566; Downs, 1957). My research does not strive to challenge these arguments because interests do matter. What it instead aims to demonstrate is that, although “agents are strategic and oriented towards the attainment of political power”, their active engagement with ideas informs their strategies, meaning that “ideas function as both a resource and a constraint for … interest-oriented agents” (Carstensen, 2011b, p. 611).

The UK Government referred to policy ideas on welfare reform by the ASI. In NZ, conflicting policy ideas on the welfare state between the Treasury and broader welfare advocates within the Labour Government, including then-Prime Minister David Lange, constrained the RCSP from effectively reinforcing Labours’ strategy to secure electoral victory in the forthcoming 1990 election. Hence, the influence of ideas is significant because “ideational battles occur” both beyond and within governmental organisations (Carstensen, 2011b, p. 606). Moreover, policy agents can find that an incremental ideational approach to changing policy is in their electoral interests “to capture the … electoral middle ground,” as reflected by both the NZ (1987) and the UK (1987) Governments’ respective electoral victories (Carstensen, 2011a, p. 608; Barnes & Harris, 2011). This reinforces the importance of ideas in cross-national policymaking and how agents engage with the elements of meaning characterising said ideas while also being mindful of the role held by surrounding domestic structures that impede or facilitate the application of these ideas into a given policy.

The purpose here is not to sacrifice the role of interest-theory-based accounts to understand agency behaviour but highlight the essential and influential role ideational processes have on agency behaviour and how this is a complementary part of a dynamic relationship. This depends on how conceptualised policy agents, which concerns bricoleurs forming hybridised policy proposals incrementally implemented over time. Ideas play a vital role in cross-national policymaking.

Conclusion

Analysing the differences in social policy between NZ and the UK, which implemented similar economic policies between 1984 and 1990, required an ideationally focused critical lens. Existing literature analysing both countries during this period fails to explain this variance as many focused on the similarities. This research applied a policy transfer approach combined with a constructivist analysis through Carstensen’s theory of incremental ideational change. The dynamic relationship NZ and UK policymakers had with ideational processes impacted their policymaking during this period. Emphasising this relationship from an analytical perspective enabled this research to determine why social policy differed in each country.

The research revealed two key findings. First, social policy variance occurred due to NZ policy agents affecting change in the elements of meaning behind neoliberal policy ideas. These ideas initially opposed social policy expansion to hybridise a policy model that merged numerous neoliberal policy prescriptions and retained pre-existing approaches and norms in social policy. In contrast, the UK Conservative Government continued their neoliberal reform process by remoulding pre-existing social policy norms because they continued to view the welfare state as an economic risk contributing to heightened inflation and a burden on state expenditure. In both cases, UK and NZ policy agents engaged – both with each other, through specific ideational networks, and with policy ideas – and produced a policy that reflected a bricolage of existing and novel policy ideas pragmatically and incrementally, albeit differently.

Second, this research demonstrated the significant role of ideas in cross-national policy research in identifying causal factors that further clarify policymaking behaviour. Agents constantly interact with ideas, and their elements of meaning, to change the relationship between these existing elements or change certain elements characterising an idea. In NZ, agents in the Treasury did the former regarding Labour’s policymaking by integrating transnationally disseminated neoliberal policy prescriptions to overthrow the pre-existing adherence to Keynesian philosophy. While this changed critical elements within how a Labour Government should govern, it did not change the idea entirely. This was explicitly due to the Labour Government expressing their commitment to upholding social policy despite internal conflicts between them and the Treasury. Despite differing in social policy, the UK Conservative Government also incrementally altered certain elements in their idea of governing the country, as their policy reforms throughout, including social policy, were both controversial as they were transformative when implemented. In both instances, these changes occurred through a constant engagement by policy agents with pre-existing and novel policy ideas. Domestic structures in both countries, specifically their sharing of a first-past-the-post electoral system and certain institutions, such as the UK’s ASI and NZ’s Treasury, enabled and informed each government to enact their reforms.

The research did not seek to undermine current interest-based theoretical scholarship because agents, as in the UK and NZ, certainly have and pursue interests beneficial to preserving power. Instead, it demonstrates the significant role ideas have in clarifying these interests to agents who either engage with ideas as a resource or constraint to their given strategy.

The qualitative case study-oriented approach exhibited certain limitations, notably that findings are non-generalisable to broader instances of cross-national policymaking. Similarly, certain limitations were unavoidable; key actors relevant to this period could not be interviewed. However, my choice to sacrifice breadth and generalisability for an in-depth inquiry into two cases enabled a more nuanced analysis of the enactment of social policies in two specified national contexts between 1984 and 1990.

This study has demonstrated the significance of incorporating an ideationally focused lens to develop current understandings behind cross-national policy variance. Such an approach is complementary to policy transfer and, in the cases of NZ and the UK, reveals new perspectives and answers to explain what previous literature could not – social policy variance. An avenue for future research would be to compare the extent of ideational change during times of stability or crisis. This would provide further scope into understanding the impact of ideational processes on policymakers and perhaps contribute to the current understanding of policymaking behaviour that can sometimes prove controversial or paradoxical in NZ.

Bibliography

Acharya, A. (2004). How ideas spread: Whose norms matter? Norm localization and institutional change in Asia. International Organisation, 58(2), p. 239-275.

Albertson, K. & Stepney, P. (2020). 1979 and all that: A 40-year reassessment of Margaret Thatcher’s legacy on her own terms. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 44, p. 319–342.

Alcock, P. (1990). The end of the line for social security: The Thatcherite restructuring of welfare. Critical Social Policy, 10(30), p. 88-105.

Anckar, C. (2008). On the applicability of the most similar systems design and the most different systems design in comparative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11(5), p. 389-401.

Angresano, J. (2007). The case of New Zealand: Liberalizing the welfare state with mixed results. In: French Welfare State Reform: Idealism versus Swedish, New Zealand and Dutch Pragmatism. London: Anthem Press, pp. 91-120.

ASI (2014). Adam Smith Institute [Online] Available at: shorturl.at/hCNQY [Accessed 25 April 2021].

Ban, C. (2011). Neoliberalism in Translation: Economic Ideas and Reforms in Spain and Romania, College Park: Unpublished Dissertation.

Ban, C. (2016). Ruling Ideas: How Global Neoliberalism Goes Local. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ban, C. (2018). Ch. 4: Translation and Economic Ideas. In: F. Fernandez & J. Evans, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Politics. London: Routledge, pp. 48-63.

Barnes, J. & Harris, P. (2011). Still kicking? The Royal Commission on Social Policy, 20 years on. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 37, p. 1-13.

Benson, D. & Jordan, A. (2011). What have we learned from policy transfer research? Dolowitz and Marsh revisited. Political Studies Review, 9(3), p. 366-378.

Bevir, M. & Rhodes, R. A. W. (2003). Interpreting British Governance. London: Routledge.

Biersteker, T., Hall, R. B. (2002). The Emergence of Private Authority in Global Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Block, F. L. & Somers, M. R. (2014). The Power of Market Fundamentalism: Karl Polanyi’s Critique. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Boas, T. C. & Gans-Morse, J. (2009). Neoliberalism: From new liberal philosophy. Studies in Comparative International Development, 44, p. 137-161.

Boston, J. (1987). Thatcherism and Rogernomics: Changing the rules of the game – comparisons and contrasts. Political Science, 39(2), p. 129-152.

Boston, J. (1991). The theoretical underpinnings of public sector restructuring in New Zealand. In: J. Boston, J. Martin & P. Walsh, eds. Reshaping the State: New Zealand’s Bureaucratic Revolution. Auckland: Oxford University Press, pp. 1-26.

Boston, J. (1993). Reshaping social policy in New Zealand. Fiscal Studies, 14(3), p. 64-85.

Bourdieu, P. (1998). L’essence du Néolibéralisme. Le Monde Diplomatique, 15 December, p. 3-7.

Braun, D. & Gilardi, F. (2006). Taking ‘Galton’s problem’ seriously towards a theory of policy diffusion. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 18(3), p. 298-322.

Carstensen, M. B. (2011a). Paradigm man vs. the bricoleur: Bricolage as an alternative vision of agency in ideational change. European Political Science Review, 3(1), p. 147-167.

Carstensen, M. B. (2011b). Ideas are not as stable as political scientists want them to be: A Theory of Incremental Ideational Change. Political Studies, 59, p. 596-615.

Cheyne, C., O’Brien, M. & Belgrave, M. (2005). Social Policy in Aotearoa New Zealand. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Collier, D. (2011). Understanding process tracing. PS: Political Science & Politics, 44(4), p. 823- 830.

Docherty, D. C. & Seidle, F. L. (2003). Reforming Parliamentary Democracy. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Dolowitz, D. & Marsh, D. (2000). Learning from abroad: The role of policy transfer. Governance, 13(1), p. 15-24.

Dominelli, L. (1988). Thatcher’s attack on social security: Restructuring social control. Critical Social Policy, 8(23), p. 46-61.

Douglas, R. (1993). Unfinished Business. Auckland: Random House.

Downs, A. (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper and Row.

Easton, B. (1988). From Reagonomics to Rogernomics. In: The Influence of United States Economics on New Zealand: The Fulbright Anniversary Seminars. Wellington: New Zealand Institute of Economic Research, Research Monograph, pp. 13-41.

Easton, B. (1994). How did the health reforms Blitzkrieg fail? Political Science, 4(2), p. 205-225.

Easton, B. (1997). The Commercialisation of New Zealand, Auckland: Auckland University Press.

Evans, E. J. (2019). Thatcher and Thatcherism. Fourth ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

Evans, M., Piachaud, D. & Sutherland, H. (1994). The Effects of the 1986 Social Security Act on Family Incomes, York: Joseph Rountree Foundation.

Fowler, N. (2019). Norman Fowler – 1985 Statement on the Social Security Review. [Online] Available at: https://www.ukpol.co.uk/norman-fowler-1985-statement-on-the-social-security- review/ [Accessed 26 April 2021].

Gilardi, F. (2010). Who learns from what in policy diffusion processes? American Journal of Political Science, 54(3), p. 650-666.

Goldfinch, S. & Rober, B. (1993). Treasury’s role in state policy formulation during the post-war era. In: B. Roper & C. Rudd, eds. State and Economy in New Zealand. Auckland: Auckland University Press, pp. 56-68.

Golding, P. & Middleton, S. (1982). Images of Welfare: Press and Public Attitudes to Welfare. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Hall, P. (1989). The Political Power of Economic Ideas: Keynesianism across Nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ishak, N. M. & Abu Bakar, A. Y. (2014). Developing sampling frame for case study: Challenges and conditions. World Journal of Education, 4(3), p. 29-35.

James, O. & Lodge, M. (2003). The limitations of “policy transfer” and “lesson drawing” for public policy research. Political Studies Review, 1(2), p. 179-193.

Kandiah, M. D. & Seldon, A. (2013). Ideas and Think Tanks in Contemporary Britain. New York: Routledge.

Kelsey, J. (1997). The New Zealand Experiment – A World Model for Structural Adjustment? Auckland: Auckland University Press.

Knill, C. (2005). Introduction: Cross-national policy convergence: Concepts, approaches and explanatory factors. Journal of European Public Policy, 12(5), p. 764-774.

Kogut, B. & Macpherson, J. M. (2008). 3 – The decision to privatize: Economists and the construction of ideas and policies. In: B. A. Simmons, F. Dobbin & G. Garrett, eds. The Global Diffusion of Markets and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 104-140.

Lange, D. (2005). My Life. Auckland: Viking Press.

Larner, W. & Walters, W. (2000). Privatisation, governance, and identity: The United Kingdom and New Zealand compared. Policy & Politics, 28(3), p. 361-377.

Latour, B. (1987). Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers Through Society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Layard, R. & Nickell, S. (1989). The Thatcher miracle? The American Economic Association, 79(2), p. 215-219.

Lee, C. K. & Strang, D. (2006). The international diffusion of public-sector downsizing: Network emulation and theory-driven learning. International Organization, 60(4), p. 883-909.

Lenschow, A., Liefferink, D. & Veenman, S. (2005). When the birds sing: A framework for analysing domestic factors behind policy convergence. Journal of European Public Policy, 12, p. 797-816.

Levine, S. & Roberts, N. S. (1994). The New Zealand electoral referendum and general election of 1993. Electoral Studies, 13(3), p. 240-253.

Mabett, D. (2013). The second time as tragedy? Welfare reform under Thatcher and the Coalition. The Political Quarterly, 84(1), p. 43-52.

Mahoney, J. (2004). Comparative-historical methodology. Annual Review of Sociology, 30, p. 81-101.

Marsh, D. & Sharman, J. (2009). Policy diffusion and policy transfer. Policy Studies, 30(3), p. 269- 288.

McClure, M. (1998). A Civilised Community. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

McCluskey, N. P. (2008). PhD Thesis: A Policy Of Honesty: Election Manifesto Pledge Fulfilment In New Zealand. Canterbury: University of Canterbury.

McTaggart, S. (2005). Monitoring the Impact of Social Policy: Report on Significant Policy Events, Wellington: Social Policy Evaluation And Research.

Menz, G. (2002). More Thatcher than the real thing: Policy transfer and economic reforms in New Zealand. In: M. de Jong, K. Lalenis & V. Mamadouh, eds. Institutional Transplantation: Experiences with the Transfer of Policy Institutions. New York: Springer, pp. 137-152.

Menz, G. (2005). 3. Making Thatcher Look Timid: the Rise and Fall of the New Zealand Model. In: S. Soedergberg, G. Menz & P. Cerny, eds. Internalizing Globalisation. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 49-68.

Meseguer, C. (2006). Rational learning and bounded learning in the diffusion of policy innovations. Rationality and Society, 18(1), p. 35-66.

Meseguer, C. & Gilardi, F. (2009). What is new in the study of policy diffusion? Review of International Political Economy, 16(3), p. 527-543.

Mesher, J. (1981). The 1980 social security legislation: The great welfare state chainsaw massacre? British Journal of Law and Society, 8(1), p. 119-127.

Mirowski, P. (2013). Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown. New York: Verso Books.

Monios, J. (2017). Policy transfer or policy churn? Institutional isomorphism and neoliberal convergence in the transport sector. Environment and Planning, 49(2), p. 351-371.

Neuman, W. L. (2009). Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 7th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

Newmark, A. (2002). An integrated approach to policy transfer and diffusion. Review of Policy Research, 19, p. 152-178.

Obinger, H., Schmitt, C. & Starke, P. (2013). Policy diffusion and policy transfer in comparative welfare state research. Social Policy and Administration, 47(1), p. 111-129.

O’Brien, M. (2008). Poverty, Policy and the State: Social Security Reform in New Zealand. Bristol: Policy Press.

OECD (2021). OECD Data: Social Spending Indicator. [Online] Available at: https://data.oecd.org/socialexp/social-spending.htm [Accessed 12 3 2021].

Pierson, P. (1997). Dismantling the Welfare State? Reagan, Thatcher and the Politics of Retrenchment. Third ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reitan, E. A. (2003). The Thatcher Revolution: Margaret Thatcher, John Major, Tony Blair, and the Transformation of Modern Britain, 1979-2001. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Risse-Kappen, T. (1994). Ideas do not float freely: Transnational coalitions, domestic structures, and the end of the Cold War. International Organisation, 48(2), p. 185-214.

Risse, T. (2000). Let’s argue! Communicative action in world politics. International Organisation, 54, p. 1-39.

Schmidt, V. A. (2008). Discursive institutionalism: The explanatory power of ideas and discourse. Annual Review of Political Science, 11, p. 303-326.

Schmidt, V. A. (2017). Britain-out and Trump-in: A discursive institutionalist analysis of the British referendum on the EU and the US presidential election. Review of International Political Economy, 24(2), p. 248-269.

Schwartz, H. (2000). 3. Internationalization and Two Liberal Welfare States Australia and New Zealand. In: F. W. Scharpf & V. A. Schmidt, eds. Welfare and Work in the Open Economy Volume II: Diverse Responses to Common Challenges in Twelve Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 69-131.

Smidt, V. A. & Thatcher, M. (2013). Resilient Liberalism in Europe’s Political Economy. In: V. A. Schmidt & M. Thatcher, eds. Introduction: The Resilience of Neoliberal Ideas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1-52.

Stepney, P. (2018). Theory and methods in a policy and organisational context: international perspectives. In: N. Thompson & P. Stepney, eds. Social Work Theory and Methods: The Essentials. New York: Routledge, pp. 44-62.

Stone, D. (2001). Learning lessons, policy transfer and the international diffusion of policy ideas. Centre for the Study of Globalisation and Regionalisation, pp. 1-38.

Strom, K. (1990). A behavioral theory of competitive political parties. American Journal of Political Science, 34(2), p. 565-598.

Verger, A. (2016). Chapter 3: The Global Diffusion of Education Privatization. In: K. Mundy, A. Green, B. Lingard & A. Verger, eds. Handbook of Global Education Policy. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 105-123.

Walker, R. (2005). Words, Meaning and the Importance of Context. In: D. Gladstone, ed. Introducing Social Policy: Social Security and Welfare Concepts and Comparisons. London: Open University Press, pp. 3-19.

Weyland, K. (2004). Learning from Foreign Models in Latin American Policy Reform. Washington DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

Weyland, K. (2009). The rise of Latin America’s two lefts: Insights from Rentier State Theory. Comparative Politics, 41(2), p. 145-164.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Confronting Great Powers: New Zealand’s Nuclear Stance During the Cold War

- The False Dichotomy of the Material-Ideational Debate in IR Theory

- Neoliberalism and the Sovereignty of the Global South

- IR Theory and The Ontological Depth of the Material-Ideational Debate

- Everyday (In)Security: An Autoethnography of Student Life in the UK

- The Importance of Queer Theory: An Abridgement on Trans Healthcare in the UK