Since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, some unexpected actors have been brought under the spotlight in the context of a war: global banks. Because they didn’t want to get involved in an armed conflict, Western European governments sought to implement economic sanctions against Russia – and these sanctions have largely been implemented through the banking system. The recent weaponization of global banks is a powerful illustration that banks are not just like any type of private firms. They are essential dimension of states’ geo-economic power.

My research shows that the capacity of banks to act as central nodes in global financial flows has motivated politicians to maintain or even increase the size of their domestic banks long before the war in Ukraine. More particularly, I show that the executive branches of Western European governments have been especially sensitive to the geo-economic dimensions of banking and have consequently been reluctant to pass regulation that may have impacted their global banks. However, other state actors are less sensitive to the geo-economic dimension of global banks. In particular, parliaments are often more concerned about the traditional function of banks consisting in providing credit to firms – this concern had led them to promote smaller and simpler banks more often than their counterparts in the executive branch of the state. I show that the differentiated institutional capacity of parliaments to weigh in the policy-making process in each national jurisdiction shape the more or less positive stance of the country towards its large global banks. To do so, my research has built on quantitative text analysis of parliamentary debates as well as a comparative case study of banking regulation in France, Germany and Spain since the 2008 financial crisis (Massoc, 2022).

Evolution of large European banks and post-crisis banking regulation

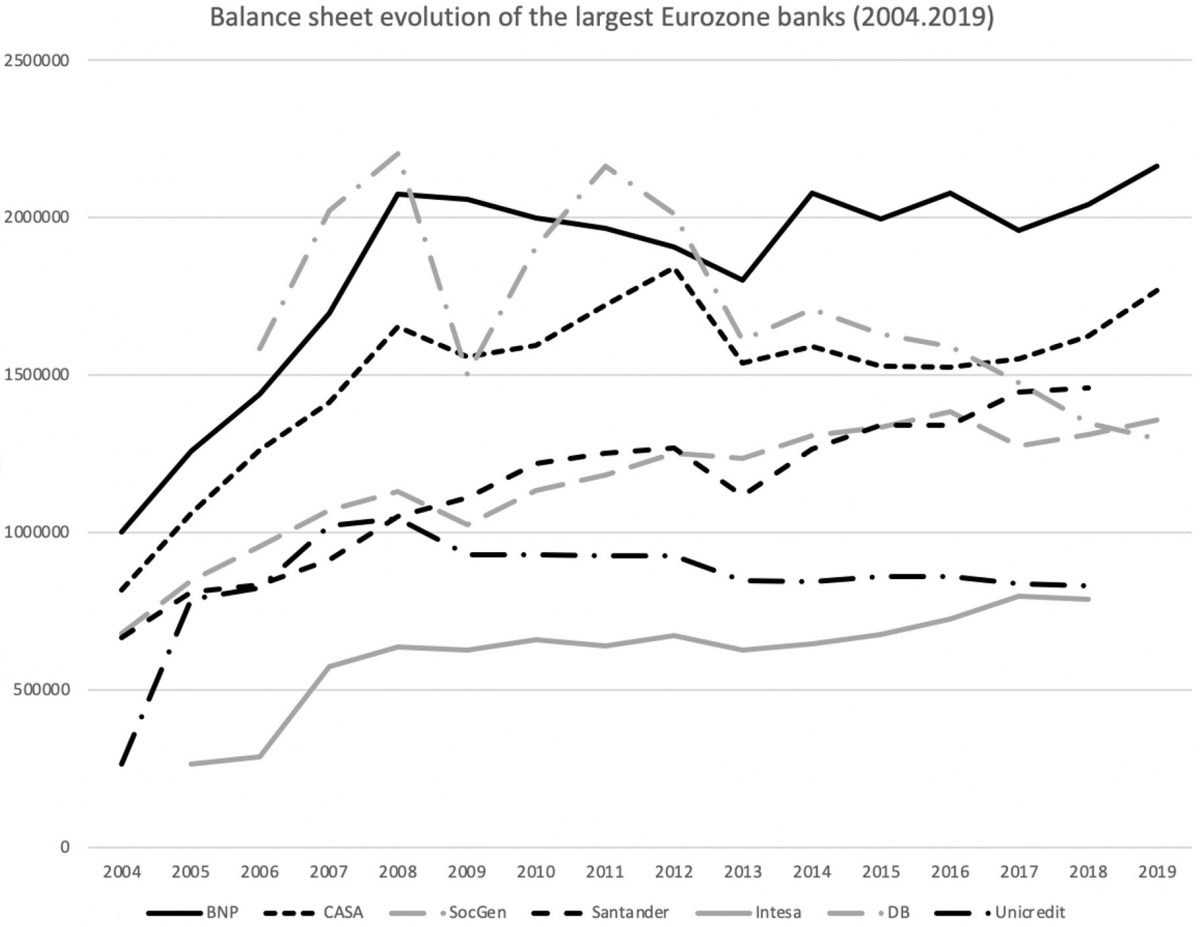

In the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis, most politicians and policymakers claimed to be on the same page as the Chief Economist of the European Central Bank, who declared in 2009 that “The simple statement that ‘if banks are too big to fail, they are too big to exist’ is a reasonable rule.” Twelve years later, the size and business models of Europe’s largest banks have largely remained unchallenged. Figure 1 shows the evolution of the eight largest Eurozone banks’ balance sheets. Except for Deutsche Bank and ING, the balance sheets have either remained stable or grown. In particular, the three largest French banks (SocGen, BNP-Paribas and CASA) as well as the largest Spanish bank (Santander) have continued to grow over this period. With the exception of one bank (Commerzbank), all of the European banks listed by the BIS as “globally systematically important” are still on this list.

A variety of market and non-market factors may explain the evolution of the largest Eurozone banks. In particular, the European Central Bank’s (ECB) so-called “unconventional monetary policies,” which amount to massive liquidity injections, have largely shaped the capacity of Eurozone banks to maintain both their lending and market activities (Carpinelli and Crosignani 2017; Braun and Gabor 2020).

However, this evolution could not have happened if there had been a political agenda to resist the expansion of large banks. Since the crisis, the main regulatory focus has been on banks’ capital requirements under the Basel III agreement. How Basel III has impacted large banks is debatable, but evidence has shown that capital requirements do not prevent large banks from growing – and to some extent they promote the complexification of balance sheets. There is also evidence that their implementation has been watered down by national regulators, especially through an accommodating implementation of internal models of asset risk weighting (Massoc 2017; Behn et al 2021). The initiation of the European banking union (EBU) also marked another major step in European banking reform. Its first pillar is the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), which brought the largest Eurozone banks under the supervision of the ECB. The second pillar of the EBU is the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM), which has harmonized banks’ resolution rules across Europe in favor of “bail-in” procedures. The SRM is supposed to prevent further banking bailouts at the expense of taxpayers. The EBU’s degree of completion, its multiple political and economic implications, and its actual effectiveness are all much debated issues. Such debates are beyond the scope of the argument developed here. What is pertinent to the present discussion is that the EBU framework is accommodating of the business models of large European market-based banks. It has never been discussed within the EBU to promote another type of (smaller and simpler) banking.

Ambitious banking reforms could have been passed both at the national and the EU levels if the political priority of national governments had been to downsize and simplify banking. The point here is that it was not their priority. A case in point to support this claim is the failure of the structural banking reform in Europe. Based on the Liikanen Report, the European Commission proposed in 2013 to separate retail from market activities in banking, which would have resulted in smaller and simpler banks, but European national governments actively opposed this proposal and ultimately prevented it from passing (Ganderson 2021, Massoc 2020).

Banks’ diminishing structural power

Is the European failure to make banks smaller and simpler due to the structural power that banks have over states? Banks have been described as the poster child of structural power as it is traditionally conceived in the political science literature: governments are structurally dependent on banks because the health of the whole economy depends on the very capacity of banks to provide credit to firms. This “privileged position” give banks political power because they can always (threaten to) cut credit to the economy in case they are dissatisfied with a certain regulation. Policymakers don’t want to risk putting the funding of the real economy in jeopardy so they don’t pass regulation that could upset them (Poulantzas 1969; Lindblom 1977; Block 1984).

The 2008 financial crisis and subsequent bank bailouts have renewed scholarly interest in the study of structural power. In this literature, scholars continue to assume that the main source of banks’ structural power lies in its unique capability to provide credit to the real economy. However, European banks’ business models have changed dramatically. Most notably, they have significantly developed their market-based activities before the crisis, giving rise to what Hardie et al. (2013) have called “market-based banking.” Accumulating evidence shows that the growing marketization of banking rather complicates the provision of credit to non-financial firms (especially small and medium enterprises (SMEs)) (Godechot 2016; Epstein 2018). Meanwhile, non-financial firms (NFCs) have further developed access to sources of funding other than bank credit (Braun and Deeg 2020). Ultimately, because they have become dependent on the markets for their own funding, banks that were formerly autonomous in their lending decisions have undermined their decisional power in lending to firms. These three trends have actually decreased the banks’ structural power as it is traditionally conceived.

The geo-economic foundations of banks’ power

If the power of banks is no longer predicated on the activity of facilitating real economic investment, what then is the basis for their continuing structural power? I argue that banks are still immensely powerful due to their geo-economic dimension.

Farrell and Newman (2019) write that,

States increasingly ‘weaponize interdependence’ by leveraging global networks of informational and financial exchange for strategic advantage. (…) Specifically, states with political authority over the central nodes in the international networked structures through which money, goods, and information travel are uniquely positioned to impose costs on others.

These authors underlined the importance of “chokepoint effects,” which describe the capacity of some states to limit or penalize the use of hubs by third parties (e.g. other states or private actors). Economic statecraft resides in the manipulation of access to markets as well as in the capacity to interrupt business activities and access to funding. Because hubs offer extraordinary efficiency benefits, and because it is extremely difficult to circumvent them, states that can control hubs have considerable coercive power, and states or other actors that are denied access to hubs can suffer substantial consequences.

Global banks are at the core of global financial flows of different kinds. Importantly, the global financial system depends upon the intermediation of market-based banks as providers of global liquidity. Only very large banks with expertise in complex finance are able to become hubs for global liquidity (Beck 2021; Lapavitsas 2013). When the new battleground is described “the interconnected infrastructure of the global economy” (Leonard 2016), European banks may use their financial power to disrupt liquidity provision in the interest of geo-economic considerations. As a consequence of the central position of their banks, some countries are able to obtain significant concessions without taking visible coercive measures (Drezner 2003). Large banks must thus be seen as signalling devices of potential practices of state power. This was made obvious in February 2022 when Western European governments sought to implement economic sanctions against Russia, but geo-economic considerations of state actors explain their positive stance towards large global banks already since the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

Different sensitivities of state agencies towards banks’ structural power and their resulting priorities towards banking

Actually, one category of state actors is particularly sensitive to the geo-economic dimension of banks: the executive branch, impersonated in the matters of banking by the Ministry of Economy and Finance. The executive branches of governments indeed traditionally dominate matters related to foreign policy, diplomacy and war. Their function of protecting the sovereign nation from foreign enemies and their concern with state power abroad make it more likely that executive branches will be sensitive to the geo-economic power of banks. In contrast, parliaments are directly elected and more directly accountable to constituents, and their concerns with their ability to work and live in good conditions on a daily basis. Complaints about the lack of credit for local firms may thus impact MPs more easily than ministers of finance. That makes them generally more sensitive to the “credit” foundations of banks’ structural power. Sensitivity to the provision of credit to the real economy is more likely to translate into a preference for smaller and simpler banks. Meanwhile, sensitivity to geo-economic power is more likely to translate into a preference for larger and more complex banks.

Discourse analysis of parliamentary debates

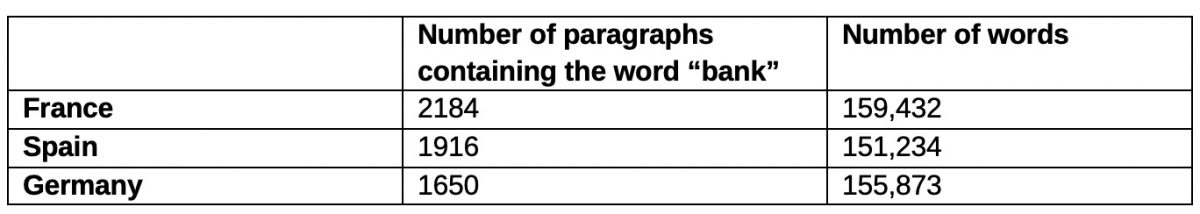

To support this claim empirically, I performed a discourse analysis of parliamentary debates concerning banking issues in France, Spain and Germany. On the public websites of the French, Spanish and German parliaments, I searched the minutes of the plenary parliamentary debates between 2010 and 2020 to return debates containing the keyword “bank” in the three national languages. Based on these samples, I constructed a database composed of all paragraphs containing the word “bank.” I took out paragraphs with expressions in which the word “bank” typically did not refer to the financial institutions (e.g. bank of data), as well as when used in reference to the central bank. Table 1 presents the number of paragraphs and the total number of words in the databases for each of the three countries.

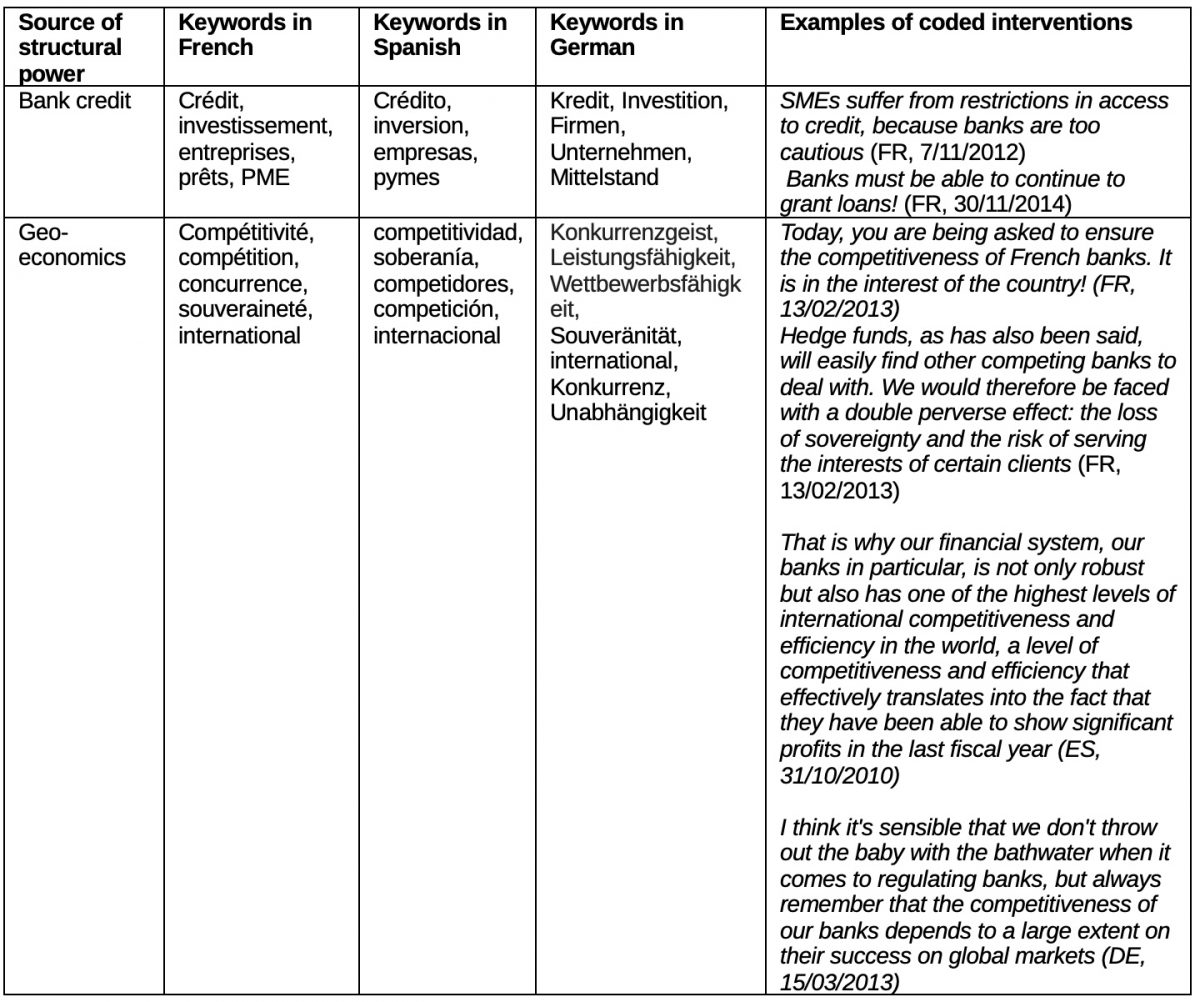

The words that politicians used when defending their political positions towards banking during the debates revealed what dimension of banking mattered most to them. Based on an initial reading of sub-samples of the parliamentary debates, I distinguished between the following the two different sources of structural power that lawmakers utilize to justify their positions on any given policy: 1) banking credit to the economy (bank credit); and 2) banks’ competitiveness on global markets and national sovereignty (geo-economics). Different keywords correspond to different sources of structural power. Table 2 presents these keywords in the three national languages, as well as their translation in English and illustrative quotes for each category.

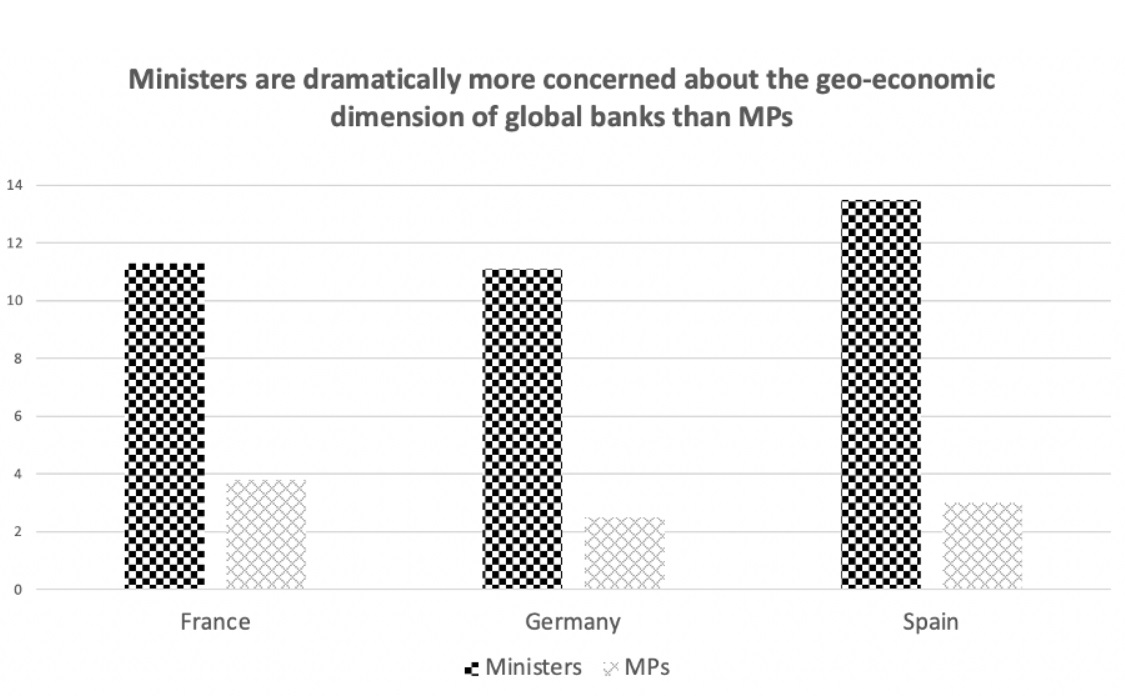

The assumption of the analysis is that words that politicians used when defending their political positions towards banking during the debates revealed what dimension of banking mattered most to them. Actors using words like “loans” more often are more sensitive to the economic role of banks. Actors using words like “sovereignty” more often are more sensitive to the geo-economic role of banks. The results of this analysis, pictured in Figure 2, show that in the three countries, Ministries of Economy and France are significantly more concerned about the geo-economic dimension of large banks. In France, 11,3% of their intervention related to banking are concerned with geo-economic considerations, which is more than the proportion of their intervention concerned with banks’ provision of credit to the real economy. Inversely, only 3.8% of parliamentarians’ interventions are concerned with geo-economics, when 12,1% of their interventions are concerned with banks’ provision of credit to the real economy. The same pattern holds in the three countries.

There are some slight variations in terms of which source of structural power matters most to politicians in each country. Yet, there is one constant: ministers are significantly more sensitive to the geo-economic power of banks than MPs. This finding goes against the assumption in the comparative political economy, according to which state officials would defend policies in coherence with their national varieties of capitalism or specific growth models. However, my findings show that ministries share the same concerns and preferences regarding large banks – regardless of the economic role occupied by those banks in their own political economies (see Quaglia and Royo 2014; Massoc 2020).

Another interesting result (not shown here) is that a partisan divide between the left and the right is visible among MPs: compared with left MPs, right MPs were more concerned with banks’ competitiveness (but still less so than ministers). In France and Spain between 2010 and 2020, there were governments with right and left majorities. In Germany, coalitions over this period varied and there were ministers of finance from the right and from the left. However, in contrast with MPs, in none of the selected countries was there a partisan divide demonstrated among ministers. Ministers are thus more sensitive to the geo-economic power of banks regardless of their party affiliation (and regardless of the economic role played by banks in their respective country).

I have suggested here that executive branch (especially finance ministries) prioritize geo-economic considerations over investment in the real economy, while parliaments prioritize investment and credit when it comes to banking policies. Other aspects of my research shows that banking policy outcomes indeed largely depend on the balance of power between those two political actors (Massoc 2022a, Massoc 2022b).

Conclusion

To explain the post-crash banking strategies of major European states, my research shed light on an overlooked aspect of banks’ structural power: their geo-economic importance in the eyes of key state officials. Due to their central position in the global financial system as providers of global liquidity, the weakening (or strengthening) of large domestic banks may cause the weakening (or strengthening) of state power in the global political economy. Thus, the structural power of large banks also derives from the fact that they are perceived as a crucial tool of statecraft.

This research has implications for the democratic debates about the role of finance in society. The responsibility for detrimental policy choices is often attributed to powerful economic actors and to the incapacity of state actors to resist them. Yet, my research shows that banking strategies largely depend on state actors’ preferences themselves, suggesting that politics matters, even when the fate of very powerful actors is at stake. Finally, public debates about finance tend to focus on the productive investment (or lack thereof) of banks and other financial actors because engaged citizens and social activists see this as the most important aspect of finance. Those activists may be right that this should be the case, but they miss an important point: key policymakers have other considerations in mind when they think about finance. To weigh in more effectively, social actors need to address and discuss the geo-economic dimension of global banks’ structural power.

References

Beck, Mareike. 2021. “Extroverted Financialization: How US Finance Shapes European Banking.” Review of International Political Economy, 1–23

Behn, Markus, Rainer Haselmann, and Paul Wachtel. 2016. “Procyclical capital regulation and lending.” The Journal of Finance 71, no. 2: 919-956.

Block, Fred. 1984. “The Ruling Class Does Not Rule: Notes on the Marxist Theory of the State.” In The Political Economy. Routledge.

Braun, Benjamin, and Richard Deeg. 2020. “Strong firms, weak banks: The financial consequences of Germany’s export-led growth model.” German politics 29, no. 3: 358-381

Braun, Benjamin, and Daniela Gabor. 2020. “Central Banking, Shadow Banking, and Infrastructural Power.” In The Routledge international handbook of financialization, pp. 241-252. Routledge.

Carpinelli, Luisa, and Matteo Crosignani. 2017. “The effect of central bank liquidity injections on bank credit supply.”

Drezner, Daniel. 2003. “The hidden hand of economic coercion.” International Organization 57, no. 3: 643-659

Epstein, Gerald. 2018. “On the Social Efficiency of Finance.” Development and Change 49, no. 2: 330–52.; 3

Ganderson, Joseph. 2020. “To Change Banks or Bankers? Systemic Political (in)Action and Post-Crisis Banking Reform in the UK and the Netherlands.” Business and Politics 22, no. 1 (March): 196–223.

Godechot, Olivier. 2016. “Financialization Is Marketization! A Study of the Respective Impacts of Various Dimensions of Financialization on the Increase in Global Inequality.” Sociological Science 3: 495–519.

Hardie, Iain, and David Howarth. 2013. Market-Based Banking and the International Financial Crisis. Oxford University Press.

Quaglia, Lucia, and Sebastian Royo. 2015. Banks and the political economy of the sovereign debt crisis in Italy and Spain. Review of International Political Economy, 22(3), pp.485-507

Lapavitsas, Costas. 2013. “The Financialization of Capitalism: ‘Profiting without Producing.’” City 17, no. 6 (December 1): 792–805.

Leonard, Mark. 2016. “Connectivity Wars : migrations, finance et commerce, champs de bataille du futur ?” Revue Defense Nationale N° 789, no. 4: 79–83

Lindblom, Charles E. 1977. Politics and Markets. Basic Books. New York.

Massoc, Elsa Clara. 2017. “When Adoption is not Enforcement: The Differentiated Enforcement of Banks’ Capital Ratio Requirements across Europe.” Berkeley Journal of Public Policy, (Spring Issue).

Massoc, Elsa Clara. 2018. Banking on States? The divergent trajectories of European finance after the crisis. University of California, Berkeley.

Massoc, Elsa Clara. 2020. “Banks, power, and political institutions: the divergent priorities of European states towards “too-big-to-fail” banks: The cases of competition in retail banking and the banking structural reform.” Business and politics 22, no. 1: 135-160.

Massoc, Elsa Clara. 2022a. Having banks ‘play along’state-bank coordination and state-guaranteed credit programs during the COVID-19 crisis in France and Germany. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(7), pp.1135-1152

Massoc, Elsa Clara. 2022b. “Banks’ Structural Power and States’ Choices Over What Structurally Matters. The Geo-Economic Foundations of State Priority Towards Banking in France, Germany and Spain.” Politics and Society, (forthcoming).

Poulantzas, Nicos. 1969. “The Problem of the Capitalist State.” New Left Review, no. 58: 67.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1: Balance sheet evolution of the eight largest Eurozone banks (€ mln) between 2004 and 2019 (Source: Banks’ annual reports)

Figure 2: Results of the text analysis

Table 1: Database composed of paragraphs in parliamentary debates containing the word “bank”

Table 2: Key words used to illustrate each type of structural power with examples

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Development, Central Banks and the International Monetary System

- Politics of Banking in Europe: Global Banks and Domestic Institutional Legacies

- Opinion – One Year In, Germany’s Traffic Light Coalition Already Looks Overwhelmed

- Opinion – Turkish Foreign Policy after the 2023 Elections

- Opinion – European Credibility and the Illusion of Normative Power

- Coexisting Influence: The Sino-American Competition in Europe