This is an excerpt from McGlinchey, Stephen. 2022. Foundations of International Relations (London: Bloomsbury).

The world today may seem to be in disarray. However, by historical standards, it is actually relatively orderly and fixed into place. Those that were born in the early part of the last century lived (if they were fortunate enough to survive) through a global pandemic, a global recession and two world wars. Life in prior centuries was even more perilous. Hence, there is no better place to start with International Relations than by explaining how the modern global system came into being, primarily out of the ashes of such events. This chapter deals with what can be described as the conventional origin story of International Relations. It sets out that International Relations as a discipline, and the global system it seeks to understand, was (and still is) dominated by warring nation-states that over time became somewhat moderated by international organisations and the characteristics that they embody – such as diplomacy and trade. Late in the story, individual human beings began to have limited agency. As the two chapters that follow this one will later detail, this origin story is under significant critique due to its limitations. Yet, it remains important as a starting point in any journey through International Relations to understand the history of the academic discipline by overlaying it on significant global events – as this chapter does.

The foundations of International Relations

You may have been drawn to studying International Relations for many reasons. But it is likely that part of what shaped your thinking began with a memorable event – perhaps one that occurred in your own lived experience or made it to the headlines. Such events are diverse and fall into many categories. As the book progresses, we will focus on those more. However, historically, significant events have typically involved violence between peoples through warfare and to a lesser extent large-scale regional or global economic events (Box 2.1). Indeed, it was the issue of warfare, and the seemingly endless occurrences of it, that birthed the discipline of International Relations in 1919 in the United Kingdom at Aberystwyth, University of Wales. Later that same year, Georgetown University in the United States followed suit and a trend had thus been established that universities should study and teach International Relations. Before long, there were groups of scholars spread across different continents working on one principal issue: how to build a discipline that could explain, and potentially solve, the problem of warfare.

The year 1919 was a landmark for many reasons. Not only was it the birth-year of International Relations as a discipline, but it also followed the end of the First World War (1914–18) which involved over thirty states and resulted in over 20 million deaths. Building on this, a common feeling at the time was that a war of such scale would not, or could not, happen again due to the financial costs and the toll it took on human life. Despite this, it was surpassed only twenty years later by an even more deadly conflict, the Second World War (1939–45), which took the lives of approximately 75 million people, 2.5–3 per cent of the world’s population at the time. The Second World War is the most significant war in history due to its scale and impact. It reinforced to scholars that warfare seemed to be endemic to humankind’s past and was therefore likely to be a central problem in our future. This reflected the so-called first ‘great debate’. Firstly, there were those who sought to develop the discipline with scholarship that sought to manage warfare. This would be done by developing and promoting strategies to help states manage their participation and survival in the inevitable wars of the future. Secondly, there were scholars who sought to focus on how war could be gradually replaced, or downscaled, by emphasising the benefits of established patterns of peaceful interaction (mainly trade) and building new structures that would restrict war and formalise diplomacy (international organisations) such as the United Nations.

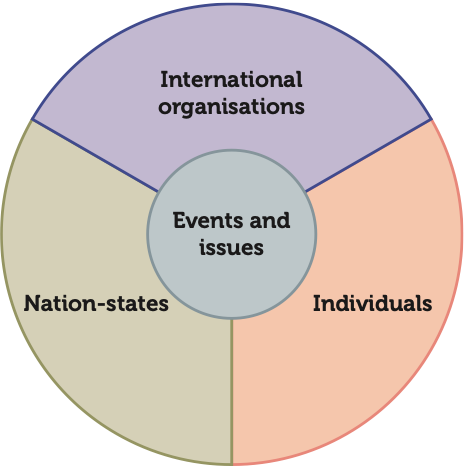

This early period left us with a discipline that focused on two key actors within the global system: (1) nation-states, the formal name for the political communities in which each of us lives and (2) international organisations, which provided a forum for states to discuss their differences whilst also helping to facilitate international trade. Gradually over time, a third element would emerge within the system: individual human beings. This was due to the rising issue of human rights, inspired by the atrocities of the Second World War and a desire to prevent that kind of mass suffering and death from happening again. Yet, it would take many more decades for individuals and the non-state groups they sometimes form to more fully rise to prominence. These three key actors of International Relations – nation-states, international organisations and individuals – were all in place by the mid- twentieth century and they still encompass the basic shape of how we make sense of the world today.

In attempting to make sense of history in all its complexity, scholars often use a simplification device to break the last 100+ years into different ‘eras’ (defined periods of time) as seen in Box 2.1. For example, the post-9/11 era consumed much of the debate in International Relations for the first two decades of the twenty-first century. In a darker sense than with human rights, it reinforced the growing importance over time of the actions of individuals – this time manifested through non-state terrorist groups. It is hard to say what the characteristics of our ‘present’ era are, that will only emerge in hindsight. However, we can say it is likely to be defined by responses to shared threats and shared opportunities beyond terrorism, which is no longer a top order global issue when taken against pandemic disease, climate change and new patterns of state rivalries.

The making of the modern world

Of all International Relations’ key actors historically, the emergence of the nation-state is the most important in terms of how the global system is shaped. Today, there are 193 defined and internationally recognised territories, which we formally call nation-states (or more commonly just ‘states’). To fully understand their importance, we need to look further back in history.

In Westphalia in 1648, part of today’s Germany, a peace treaty was agreed between a set of warring parties that had won the Thirty Years War (1618–48). With over 8 million dead, the so-called ‘Peace of Westphalia’ was notable not just for ending what had been a brutal war, but also for providing the origins of our modern global system. Prior to Westphalia, Europe had been comprised of a fluid set of city states and smaller territories, many of which were overseen in some way by the church (under the guise of the ‘Holy Roman Empire’), which provided a guiding set of principles to each ruler (see Ringmar 2017). Under this arrangement, borders and the distribution of power were unclear and often undefined. The Peace of Westphalia set out a system whereby authority going forward would be based on the political idea of sovereignty, rather than religious structures. Formalising this, each participant in the Treaty agreed on a set of defined borders marking their territory, which the others recognised in turn. This led to the redrawing of the European map and the gradual emergence of the idea of today’s nation- states as territorially bound units, recognised by other such units as mutually sovereign. Sovereignty came hand in hand with the principle of non-intervention of a foreign power in another state. Nevertheless, non-intervention has always been a point of tension – especially when relations between states break down.

Of course, peace did not come to Europe for long. In fact, Europe saw an ever-escalating series of wars for several hundred years thereafter, ultimately culminating in the two world wars. As power was (post-Westphalia) seen in the accumulation of territory, and the resources and peoples therein, many leaders sought to expand their territory by taking over the territory of others. This led to frequent conflicts that regularly redrew the European map as existing states grew (or shrank) in size, new states were created, and others vanished entirely. It escalated further as European powers exported their continental rivalry to Africa, Asia and the Americas, which they raced to colonise (control a foreign territory and its people). As a result, by 1945, one third of the world’s population were living under colonial rulers.

Following the Second World War, the global system began shifting to incorporate ideas of human rights and to recognise the illegitimacy of empire. This change was broadly inspired by the growing power of the United States, which had emerged from the Second World War in a stronger economic and political position relative to the other powers. It sought to use that leverage to influence a different world order beyond empire. Considering that the United States had freed itself from the colonialism of the British in the late 1700s during its own struggle for independence, its ideas when matched with its growing influence had sufficient gravity to reorder the system. Scholars have called this the beginning of a period of ‘pax Americana’ denoting the United States’ key role internationally from this point forwards.

The process of decolonialisation did not happen overnight, but gradually through the second half of the twentieth century empires were almost entirely dissolved. A system of establishing self-determination for formerly colonised peoples was overseen by the newly formed United Nations. In that system, those colonised peoples had only one path to independence – becoming nation-states along the very lines Europeans had established in 1648. This process gradually gave us the world map we recognise today as new borders were drawn worldwide. As had been the case in Europe, this was not always a peaceful process and a range of challenges to sovereignty, both internal and external, continue to this day across all continents. In that sense, our world map undergoes occasional updates as this process evolves with time.

The ubiquity of sovereignty in today’s global system, embodied in the nation-state and the quest for peoples who do not have a state to form one, is best represented numerically. In 1945 there were fewer than seventy nation-states. Today, there are almost 200. In that sense, today’s global system – represented by the division of the earth into territorially sovereign units – is a system made first in Europe and then exported to the rest of the world. It overrode pre-modern and alternative forms of arranging peoples and distributing power. It endures to this day as the so-called global ‘Westphalian’ system, as key elements of the logic and structure trace back to 1648.

Beyond the understanding of the Westphalian system and the ever-increasing patterns of historical conflict it led to, the Cold War, which emerged in parallel to the decolonisation process, is of central importance in reminding us that large-scale war was not over in 1945. Pax Americana translates from Latin as ‘American peace’, suggesting that the new values of the global system would lead to a more peaceful world than the one overseen by the frequently warring European colonial powers. However, while there has been no third world war, large-scale state conflict would evolve to take on different forms – primarily due to the arrival of a new technology, nuclear weapons. After the first uses of an atomic bomb by the United States on Japan in August 1945, reports and pictures of the devastation caused by the two bombs that the United States dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima confirmed that the nature of warfare had changed forever. As one reporter described the scene: ‘There is no way of comparing the Atom Bomb damage with anything we’ve ever seen before. Whereas bombs leave gutted buildings and framework standing, the Atom bomb leaves nothing’ (Hoffman 1945).

Nuclear weapons were soon developed by other states, resulting in an entirely new set of conditions in the global system. It may seem strange but, despite their offensive power, nuclear weapons are primarily held as defensive tools – unlikely to be ever used. This is due to a concept central to IR known as ‘deterrence’. By holding a weapon that can (if used) endanger the very existence of an opponent by potentially wiping them out, such an opponent is unlikely to attack you as the risk is too high. Especially if your nuclear weapons can (at least partially) survive that attack and allow you to retaliate. This is why states frequently move their nuclear weapons around, place them in submarines or aircraft, and even sometimes install them beyond their borders by agreement with an allied host state. In an environment as insecure as the Cold War, gaining a nuclear arsenal was a way to achieve deterrence from being attacked and thereby a measure of security that was not otherwise attainable. And tens of thousands of nuclear weapons were built and stockpiled by states during the Cold War. Underlining the logic of deterrence, nuclear weapons were never again used in anger after their initial use by the United States in 1945. Yet, in recognising the danger of the unmoderated spread of these weapons, a norm of non-proliferation of nuclear weapons became one of the central ideas of our global system, which is explored later in the chapter in the first case study.

The Cold War was responsible for the historical image of a world divided into three zones. The ‘First World’ was the ‘Western’ nations (this is where the term ‘the West’ comes from). These states were allied with the United States, broadly followed an economic system of capitalism, and (at least aspirationally) a political system of liberal democracy. The ‘Second World’ was the Soviet Union and a range of ‘Eastern’ states that were governed predominantly by communist (or socialist) parties who rejected capitalism as an economic model. This conflict between the first and second world went beyond economics and created two irreconcilable international systems – leaving other states a stark choice to operate within one system or the other. That led to some states opting out and declaring themselves ‘non-aligned’ – creating a ‘Third World’. As most of those states were newly formed and/or developing it became a term often used to describe economically poorer states and is still sometimes used as such.

Despite the added ideological element of communism versus capitalism, the Cold War resembled other wars before it in that it became a battle for control over territory. Instead of meeting directly on the battlefield, both sides took part in ‘proxy wars’ as they fought to either support or oppose elements within states who sought to (or appeared to) move between the First and Second Worlds. The most well-known instances of this occurred in Asia, in Korea (1950–3) and Vietnam (1955–75), each of which resulted in several million deaths. As this took place in a time of decolonisation, the goal in this period was not to be seen to directly conquer other states, but to influence their political and economic development and in doing so increase the power of one ‘World’ and diminish the other.

The Cold War ended when the Soviet Union collapsed internally between 1989 and 1991 due to endemic corruption, popular resistance and economic decline. The ‘Second World’ was therefore no more, having lost its anchor. Virtually all of the world’s states then transitioned to capitalism, if they had not already done so. At this point, the term ‘globalisation’ became widely used by scholars and policymakers more generally to describe the process of the First World’s image gradually becoming representative of the entire world. For the first time in history a truly ‘global’ system had been born. States then became categorised more loosely within that global system by their economic levels of development post-1991, with ‘Global North’ sometimes used to represent the most historically developed economies, and ‘Global South’ essentially replacing the term ‘Third World’.

The Cold War is therefore an interesting culmination in our journey of understanding the global system as being one comprised of historically warring nation-states. In this period, and continuing into the present, nuclear weapons helped prohibit the type of large-scale war seen pre-1945. In that sense, although the Cold War is over, it demonstrated a point in history where the global system changed materially in terms of how states can act internationally, especially when in conflict. This materially shaped the development of the discipline of IR and also gave way to the modern image of a world embodied by one global system. Not only has this changed the nature of warfare, it has also emphasised the importance of non-violent forms of engagement by states, allowing us to explore other elements in the system.

Beyond a world of warfare?

When military theorist Carl von Clausewitz remarked in the early 1800s that war was the continuation of policy by other means, he sought to normalise the idea of war in politics. Indeed, his words were reflective of the world at that time, as has been explored earlier in the chapter. But his words also indicated that actions short of war are available to help states achieve their objectives. These are typically the actions of diplomats. Their work is often far less expensive, far more effective and much more predictable a strategy than war. In fact, unlike in centuries gone by when war was common, diplomacy is what we understand today as the normal state of affairs governing international relations. When understood in tandem with the growing importance of international trade and the associated links between individuals in today’s global system it allows us to expand our journey through history while also adding more analysis to account for why we have not had a third world war after witnessing two in short succession in the twentieth century.

While you will now be familiar with the concept of war in its varying forms, diplomacy, due to its nature, may present itself as something alien or distant. Diplomacy is most often an act carried out by representatives of a state, usually behind closed doors. In these instances, diplomacy is a silent process working along in its routine (and often highly complex) form, carried out by rank-and-file diplomats and representatives. More rarely, diplomatic engagements can drift into the public consciousness when they involve critical international issues and draw in high-ranking officials – and in tandem the media. An example of this would be a high-profile event marking a major peace agreement such as the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt in 1978, in which the respective leaders appeared together and shook hands – an unexpected gesture considering the deep tensions between both nations which had led to several wars over prior decades.

Records of regular contact via envoys travelling between neighbouring civilisations date back at least 2500 years. They lacked many of the characteristics and commonalities of modern diplomacy such as embassies, international law and professional diplomatic services. Yet, communities of people, however they may have been organised, have usually found ways to communicate during peacetime and have established a wide range of practices for doing so. The benefits are clear when you consider that diplomacy can promote exchanges that enhance trade, culture, wealth and knowledge. The applicable international law that governs diplomacy – the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (1961) – references only states as diplomatic actors. Yet, the global system also involves powerful actors that are not nation-states. These include international organisations, which regularly partake in areas of diplomacy and often materially shape outcomes. For example, the United Nations materially shaped diplomacy in the regulation of nuclear weapons – which will be covered in the first case study later in this chapter.

Building on diplomacy, trade is another means to mitigate war. When the Cold War ended in 1991 the idea of global trade came of age. There were no more images of different worlds but instead an image of one world open for business. Still a world of nation-states, but one where the barriers between them were at a historical low and a system of shared practices (such as resolving disputes diplomatically) was enshrined in international organisations. The complex nature of global trade, where each nation-state’s economy is dependent on imports and exports to other states, is another development that makes war less likely. This is especially evident amongst the bigger powers in the global system who would likely be near-bankrupt and devoid of important commodities without the trade they generate between their peoples and businesses. The Covid-19 pandemic underlined this as, despite the unprecedented shutdowns of borders and restrictions on the movement of people, global trade – seen via the movements of goods and services – continued due to its necessity. Even the vaccines that were developed by pharmaceutical companies in certain states could not be manufactured at any scale without the materials and services found elsewhere.

What also makes war less likely is the fact that due to the instant communications we now enjoy via smartphones and global media, we can more easily see ‘the other’ as fellow human beings and as a result, it is much harder to justify acts of state aggression and to rally citizens to support a war. It is also easier to see (and therefore empathise with) individual human suffering, whether from war or from other manmade or natural factors, in other parts of the world. In this sense, the arrival of the globalised world in the 1990s also coincided with the gradual mainstreaming of ideas such as human security that took place both in the world of policymaking and in International Relations scholarship. It was as the twentieth century ended, the bloodiest century in recorded history, that individuals (and the groups they sometimes comprise) rose to prominence in the global system. In that sense you might view history as a dark place for people, but the foundations laid in the 1940s to emphasise the importance of human beings within the global system are gradually becoming more visible, as is explored further in the second case study later in the chapter.

Globalisation, especially when taken to be an unstoppable process within today’s global system, raises a number of questions. When we try to answer these questions, we quickly find new ones emerging. For example, if we settle on an idea of globalisation as the emergence of a shared global culture where we all recognise the same symbols, brands and ideals, what does that mean for local products and customs that may be squashed out of existence? Examples like this build around the question of whether globalisation is more negative than positive. In this sense, it can be seen to represent the imposition of Western political ideas and neoliberal capitalist economics – which can be viewed as unrepresentative and/or exploitative. Critiques such as this have inspired an anti-globalist (or ‘alter-globalism’) movement which is active in society and academia (see Chang 2002). The wide-ranging debate that just one term evokes is characteristic of the discipline of International Relations itself and the complexity it attempts to navigate. As noted earlier, globalisation also comes with a darker side via the opportunities it provides for criminals and terrorists to operate more effectively. Yet, beyond these issues, it is a useful way to visualise the importance of global trade and interconnectedness in a tangible sense. When taken alongside diplomacy it offers a more holistic picture of the ways states have options beyond war in today’s global system.

Adding trade and diplomacy, and the international organisations that facilitate them, allows us to see the world as one that is not static. New elements can sometimes appear and when they do, they can alter the nature of the system. Indeed, when recalling the presence of nuclear weapons, another factor within our system that disincentivises major war, it is clear to see that there are many reasons why today’s world is more peaceful in absolute terms than it has been historically. This does not take away from the reality that war still occurs, both between states (interstate war) and within states (civil war or intrastate war). Indeed, there are hundreds of instances of these post-1945. Yet, unlike in historical situations, these have not escalated to become systemic events (large-scale regional or world wars). All of this does not mean that major war is impossible. It just indicates that due to the shape of today’s global system, such a large-scale conflict is less likely to occur than in the different systems of the past.

It would be deceptive to end the origin story of International Relations without re-emphasising the role of the nation-state. Despite the other key actors that have emerged within the system, it is still only the state that holds sovereignty. This remains the true bottom line in terms of power, and this is also reflected in International Relations scholarship which has traditionally been very state centric. When Covid-19 was officially declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (denoting an epidemic occurring in multiple places) the decentralised and individualistic behaviour of states in response was more reminiscent of historical patterns than that of a supposed interconnected, globalised world. Rather than work together, states acted individually – often at odds, or in competition, with each other. This served as a reminder of their unmatched power to shape events within the global system. Later in the crisis when the race to deploy vaccines became the dominant objective, most states continued this path by competing to secure doses for their own populations first rather than prioritising international schemes (such as COVAX) to ensure everyone had equal access to vaccination.

Yet, a note of optimism. Major historical events, especially those that involve global crises (as noted throughout this chapter), do tend on average to result in shifts over the longer arc of history that come to improve how international relations operates. This typically only becomes clear in hindsight once the instinctual behaviour of states for short-term actions and reactions to crises gives way to opportunities for collective measures and working together.

CASE STUDY 1: Regulating nuclear weapons

The quest to regulate nuclear weapons offers a glimpse of interactions between states that were sworn enemies and had little in common due to incompatible economic and political systems. Yet, through diplomacy and the influence of the United Nations, they were able to avoid war and find ways to achieve progress in the most critical of areas. It also gives us one possible answer to the question posed at the start of this chapter as to why there has not been a third world war.

Although the United States was the first state to successfully detonate a nuclear weapon, others soon followed – the Soviet Union (1949), the United Kingdom (1952), France (1960) and China (1964). As the number of nations possessing nuclear weapons increased from one to five, there were fears that these weapons would proliferate (spread rapidly). This was not only a numbers issue. As the weapons developed, they became many orders of magnitude more destructive. By the early 1960s, nuclear weapons had been built that could cause devastation across over one hundred square kilometres. Recognising the danger, the United Nations attempted in vain to outlaw nuclear weapons in the late 1940s. Following that failure, a series of less absolute goals were advanced, most notably to regulate the testing of nuclear weapons. Weapons that were being developed required test detonations – each releasing large amounts of radiation into the atmosphere, endangering ecosystems and human health. By the late 1950s, diplomacy under a United Nations framework had managed to establish a moratorium (suspension) on nuclear testing by the United States and the Soviet Union. However, by 1961 a climate of mistrust and heightened Cold War tensions between the two nations caused testing to resume.

One year later, in 1962, the world came to the brink of nuclear war during the Cuban Missile Crisis when the Soviet Union placed nuclear warheads in Cuba, a communist island nation-state approximately 150 kilometres off the southern coast of the United States. Cuban leader Fidel Castro had requested the weapons to deter the United States from meddling in Cuban politics following a failed US-sponsored invasion by anti-Castro forces in 1961. As Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev (1962) put it, ‘the two most powerful nations had been squared off against each other, each with its finger on the button’. After pushing each other to the brink of a nuclear war, US President John F. Kennedy and Khrushchev found that via diplomacy, they could agree to a compromise that satisfied the basic security needs of the other. Over a series of negotiations, Soviet missiles were removed from Cuba in return for the United States agreeing to remove missiles they had deployed in Turkey and Italy. As the two sides could not fully trust each other due to their rivalry, the diplomacy was based (and succeeded) on the principle of verification by the United Nations, which independently checked for compliance. Building further on the momentum, in July 1963 the Partial Test Ban Treaty was agreed, confining nuclear testing to underground sites only. It was not a perfect solution, but it was progress. And, in this case it was driven by the leaders of two superpowers who wanted to de-escalate a tense state of affairs.

Although early moves to regulate nuclear weapons were a mixed affair, the faith that Kennedy and Khrushchev put in building diplomacy facilitated further progress in finding areas of agreement. In the years that followed the Cuban Missile Crisis, Cold War diplomacy entered a high-water-mark phase in what became known as a period of ‘détente’ between the superpowers as they sought to engage diplomatically with each other on a variety of issues, including a major arms limitation treaty. In that climate, progress was made on restricting nuclear proliferation.

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (1970) – often known as the Non-Proliferation Treaty – sought to channel nuclear technology into civilian uses and to recognise the destabilising effect of further nuclear proliferation. It was a triumph of diplomacy. The genius of the treaty was that it was aware of the realities of the international politics of the time. It was not a disarmament treaty as great powers would simply not give up their nuclear weapons, fearful their security would be diminished. So, instead of pursuing an impossible goal of eliminating nuclear weapons, the Treaty sought to freeze the number of nations that had nuclear weapons at the five states that already possessed them. Simultaneously, those five nations were encouraged to share non-military nuclear technology with other states – such as nuclear energy and nuclear medicine – so that others would not feel tempted to pursue nuclear weapons. In short, those who had nuclear weapons could keep them. Those who did not have them would be allowed to benefit from the non-military research and innovation of the existing nuclear powers.

Due to the well-considered design of the treaty and its enforcement, it has been highly successful. Following the end of the Cold War, the Non-Proliferation Treaty was permanently extended in 1995. Granted, it has not kept the number of nuclear nations to five, but there are still fewer than ten – which is far from the twenty or more projected before the treaty entered into force. States with nascent nuclear weapons programmes, such as Brazil and South Africa, gave them up due to international pressure. Today, only a small number of states are outside its bounds. India, Pakistan and Israel never joined as they (controversially in each case) had nuclear ambitions that they were not prepared to give up due to national security priorities. Underlining the weight of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, in 2003, when North Korea decided to rekindle earlier plans to develop nuclear weapons, they withdrew from the treaty rather than violate it. To date, North Korea remains the only state to withdraw from the Non-Proliferation Treaty.

The non-proliferation regime is not perfect, of course – a situation best underlined today by North Korea. It is also a system with an inherent bias, since a number of states are allowed to have nuclear weapons simply because they were among the first to develop them, and this continues to be the case regardless of their behaviour. Yet, while humankind has developed the ultimate weapon in the nuclear bomb, diplomacy has managed to prevail in moderating its spread. When a state is rumoured to be developing a nuclear bomb, as in the case of North Korea, the reaction of the international community is always one of common alarm. We call ideas that have become commonplace ‘norms’ and non-proliferation has become one of the central norms within our global system.

CASE STUDY 2: Human rights and sovereignty

During the Second World War, Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime that had ruled Germany since 1933 had been discovered to have undertaken a programme of exterminating Jews and other unwanted peoples such as homosexuals, political opponents and the disabled. In what is now known as the Holocaust, an estimated 17 million people were killed by the Nazis through overwork in labour camps, undernourishment and various forms of execution – which included gas chambers and firing squads. Of those, approximately six million were Jewish – two-thirds of the European Jewish population. Especially with reference to the fate of Jewish people, the phrase ‘never again’ became synonymous with these events. Not only was there a desire to prevent mass slaughter of human beings in a third world war – which would likely be nuclear – there was also a pressing desire to establish an international standard of human rights that would protect people from atrocities like the Holocaust and from unnecessary large-scale warfare.

Set up to represent all the earth’s recognised nation-states, the United Nations became ground zero for discussion of human rights. Just three years after the organisation was created, the ‘Universal Declaration of Human Rights’ (1948, pictured being held by Eleanor Roosevelt in Photo 2.5) had been agreed by virtually all of the United Nations’ member states outlining thirty articles that – in principle – extended to all the earth’s people. As a snapshot, the first three articles are as follows:

Article 1. All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Article 2. Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self- governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty.

Article 3. Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.

Upon reading this, three thoughts may cross your mind. The first is that it represents a step change in history. For the first time, an international document existed that sets all nation-states a set of benchmarks upon which their behaviour towards individuals will be judged. Secondly, the aforementioned comes from an international organisation that is now part of the global system, in addition to states. Here, it is important to understand the limits of the United Nations and the principles and declarations it may proffer. The United Nations is not sovereign. It does not have a territory, or a people. Instead it is an organisation run by, and through, the voluntary participation of its members. In that sense, it appends rather than replaces nation-state power. This leads us to the third thing that may have crossed your mind upon reading the articles above – that even with the most basic understanding they do not reflect today’s global system, which remains one scarred by warfare and well- publicised failures to protect human rights. In that sense, it is easy to regard human rights as a failure because, much like international organisations, individuals have not become sovereign the way nation-states are.

Such a conclusion, while factually true and the product of our global system’s enduring foregrounding of the nation-state, risks betraying the momentum that has gathered around human rights. Firstly, if we reverse to the pre-1945 period, states often acted with impunity by waging ever-escalating wars for selfish reasons – and also by colonising or enslaving human beings. There may be no international sovereign to impose legal punishment on states in the way a person would be prosecuted by the legal system within a state for a crime. But, the normative power of human rights is a growing element within our global system that has made such historical violations a rarity today. We can account for this further by looking at a range of international crimes that have been named and developed – with the bulk highlighting cases where states directly cause (or indirectly allow) unacceptable harm to people, including in times of war. Of these, perhaps the most well known is genocide, which denotes the deliberate killing of a defined group of people (usually defined by nationality, religion or ethnicity) – precisely what the Nazis did to Jewish people.

Building on the momentum of establishing a range of legal norms, the Responsibility to Protect (2001), sometimes referred to as ‘R2P’, was endorsed by all member states of the United Nations in 2005. It sought to build further on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and subsequent documents by establishing higher levels of punishment for the worst violations by states. In principle, this involves a reinterpretation of sovereignty (at times) to the level of the individual. To illustrate this, under the Responsibility to Protect, sovereignty can be imagined as similar to a mortgage given by a bank (the United Nations) to a homeowner (a nation-state). Should states keep up their repayments (by treating their people well) then the bank will never trouble the homeowner. However, if the state does not keep up its repayments (by acting in ways that cause its people undue harm and suffering) then that state may be repossessed by the international community, under the authority of the United Nations. In practice, this could mean that a state comes under an increasing level of actions, up to and including a regime being forcibly removed from power through invasion. The caveat is, as with any major issue involving international security, it has to be agreed by the world’s major powers – again reinforcing where the real bottom line of sovereignty lies.

The Responsibility to Protect has been invoked in well over a hundred resolutions at various levels within the United Nations, signifying that it is not just something that exists on paper, but that human rights in the decades since the Universal Declaration have come a long way. During the 2021 coup in Myanmar pro-democracy protesters even held up ‘R2P’ signs (Photo 2.6) showing how deeply and widely understandings and expectations of this norm have proliferated. Of course, some states still mistreat their people and international action is often insufficient to prevent it or stop it, or agreement on an action cannot be reached – as prolonged civil wars in Yemen and Syria demonstrate. Yet, understanding how the global system incorporates human rights in ways that go beyond the merely aspirational, and the related place of international organisations, is to understand that both the aforementioned exist in a position that is gradually challenging the once absolute monopoly on sovereignty held by states. It also adds further weight to the layer cake of reasons why there has not been a third world war – in this case adding a legal and normative architecture that restrains states from endangering human security on the scale that has been evident in history.

Conclusion

Our global system, in reality and as understood intellectually by International Relations scholars, is built on historical events. These events have resulted in a world dominated by nation-states which are influenced by international organisations in a dynamic system that has also opened a growing space for the voices and concerns of individuals. Future events will most likely continue to alter the system, just as past ones – such as the Treaty of Westphalia, the invention of nuclear weapons and the emergence of a global economic system of capitalism – have left indelible marks. Critiquing this origin story is our next step in the chapters ahead, which look deeper into our history and also ask questions of our present. We hope this will encourage you to not see this book, or the discipline it introduces to you, as something you can memorise as a series of events or static concepts. Instead, you should see International Relations as a living, challenging and sometimes confrontational journey of different perspectives. There are no correct answers for how we should understand the world. Indeed, there is no correct answer for the question considered earlier in the chapter of why we have not had a third world war. It may be because of nuclear weapons, it may be because the United Nations exists, perhaps it is born from a commercial desire to protect the global economy from a major disruption, or it may be because we just don’t want to solve disputes in that way any more due a rising norm of human rights. Each of these are relevant starting points and each may lead to different, yet legitimate, answers.

KEY TERMS: The global system

The phrase ‘international relations’ – not capitalised – is used to describe relations between nation-states, organisations and individuals at the global level. Lowercase ‘international relations’ is interchangeable with terms such as ‘global politics’, ‘world politics’ or ‘international politics’. What all these commonly used terms refer to are activities within the global system that both overlay, and undergird, life on planet earth. Traditionally, International Relations has understood the system at its most basic level as a dynamic between three key actors: (1) nation-states, (2) international organisations and (3) individuals. These key actors react to, are subject to, and sometimes shape, the events and issues that drive international relations. In reality, the picture is more complex than this and things will be unpacked further as the book progresses. Yet, simplification devices such as this, illustrated in Figure 1.1, are helpful to orient yourself.

KEY TERMS: The nation-state

‘Nation-state’ is a compound noun that joins two separate political entities together. A ‘nation’ is a group of people who share many things in common, such as language, territory, ethnicity or culture. Typically, a nation is forged over a longer period of history and shared experiences. When that nation is ruled by one system of governance, a ‘state’, the two join and form a ‘nation-state’. A state is a set of institutions, with a defined leadership, that has uncontested authority over the nation (the people). This authority is superior to any local, federal or regional government structures, which exist only through the consent of the state. A state’s power is typically expressed in political, military and legal power – but it can also include other categories such as religion. Historically, states came to rule over nations of people for many reasons, and they have taken many forms through history – often through patterns of domination rather than consent. But, taken broadly, it is most useful at this early stage to see establishing a state as a compromise that allows a nation of people to live under defined shared rules and structures, and thereby achieve a basic sense of security that allows their shared culture to endure in an insecure world.

KEY INSIGHTS: Landmark eras for International Relations

The First World War (1914–18). Before 1914, a system of agreements and actions known as the ‘concert of Europe’ was orchestrated between the larger powers in Europe aimed at preserving the status quo (keeping things as they are) in the continent. The collapse of this system led to war and the European powers, divided in two broad groupings, drew their overseas colonies and other great powers such as Japan and the United States into the conflict. At the time, it was known as the ‘Great War’ as its global scale was unprecedented.

The Interwar Years (1919–38). An initially optimistic period in which the first attempts at global governance were built, watermarked by the creation of the League of Nations, based in Geneva, which provided a forum to manage disputes through negotiation rather than war. During this period a stock market crash occurred in the United States in 1929, causing the ‘Great Depression’ that spread worldwide during the early 1930s and brought significant economic decline. This event marked out the importance of economics to the global system, especially in terms of how quickly it can cause negative effects spreading from one place to another.

The Second World War (1939–45). Certain states were unhappy with the status quo in the interwar years, most notably Germany and Japan, which sought to grow their power and acquire more territory by invading neighbouring states. This led to the collapse of the League of Nations and another world war as a group of states (the United States, China, the United Kingdom, France and the Soviet Union) formed an alliance to oppose the expansionist powers, eventually triumphing following the occupation of Germany and the surrender of Japan in 1945.

The Cold War (1947–91). The Cold War was known as such because the presence of nuclear weapons made a traditional war between the rival parties (in this case the United States and the Soviet Union) unlikely as they each had the power to destroy each other and in doing so jeopardise human civilisation as a whole. This was known as ‘Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD)’. For that reason, smaller-scale conflict and competition existed but a major ‘hot’ war, such as those in prior decades, was avoided. This period also underlined the importance of ideology in shaping global conflict, principally between capitalism and communism, which produced two incompatible international systems.

The New World Order (1991–2000). A short period following the end of the Cold War in which it was assumed that the international organisations built post-1945 (such as the United Nations) would finally come of age and provide a more secure and peaceful order based on globally shared ideas and practices. Francis Fukuyama’s idea of the ‘end of history’ (1989, 1992), in which he posited that liberal democracy was the only viable long-term political system to complement a capitalist world, watermarked the era. Yet, critics of such ideas highlighted their shortcomings as an overly Western image of world order.

The post-9/11 era (2001–19). On 11 September 2001, al-Qaeda – a terrorist group opposed to Western (chiefly American) dominance in the global system – attacked the United States by hijacking four commercial airliners and crashing two of them into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York and a third into the Pentagon (the headquarters of the US Military in Arlington, Virginia). The fourth plane crashed before hitting its target, which was presumed to be a political building in Washington, DC. The event led to the United States starting its ‘War on Terror’, seeking to rid the world of terrorists and governments that supported or enabled them. United States actions – together with further operations by al-Qaeda and similar terrorist groups – shaped the first two decades of the twenty-first century and led to material changes in the nature of both domestic, and international, politics.

The post-Covid-19 era (2020–). People have always travelled from place to place and exchanged goods and cultural artefacts. What has changed, due to advances in technology and transportation, is the speed and intensity of this process. Embodying this shrinkage of time and space, the term ‘globalisation’ is a major part of how we perceive today’s world. When the novel coronavirus that causes Covid-19 became a pandemic in 2020 it brought two points into focus. Firstly, transnational terrorism was no longer the central issue that it once was. Secondly, the pandemic questioned images of an interlinked, interdependent world as borders closed and most states initially turned inwards to tackle the problem for themselves rather than look outwards to pursue a global solution for all. Consequently, it is likely that the era that emerges from this crisis will be one where the global system’s resilience, and the very nature of globalisation, are stress tested for an extended period.

KEY TERMS: Sovereignty

When you look at a map of the world today all the earth’s landmasses are divided by lines (borders). Each of these borders are made (and remade) through historical events reflecting the key ordering principle of our global system – ‘sovereignty’ – which must be in place for a people to be recognised as a nation-state. Sovereignty has two benchmarks, both of which must exist simultaneously. First, there must be no major internal competition over who or what rules the territory. In practice this could be a parliament (or a similar set of institutions) in which power is regularly transferred to different elected officials. Or, it could be a monarch or dictator who rules until they are succeeded in some way by an equivalent figure. Second, there must be no significant external competition for that people’s territory. In practice this means that no overseas power claims ownership.

In practice, sovereignty is fluid. For example, should a state be attacked by another (an external competitor) it may result in that state being absorbed into the aggressor’s territory should they lose. In the modern day this is uncommon, but not unheard of. For example, Russia ‘annexed’ Crimea – part of Ukraine – in 2014. Additionally, if a group of people within a state start a movement (an internal competitor) and succeed this may sometimes create a differently composed state (carrying a new name and/or a new flag) occupying the same territory. We can see this in the case of China in 1949, which became the People’s Republic of China, and later in Iran in 1979, which became the Islamic Republic of Iran – both after successful revolutions. In these cases, other states gradually recognised the sovereignty of the new leadership as the internal competition had been settled. Finally, sometimes groups of people within states seek to break away and form an entirely new state. This occurred most recently when South Sudan seceded (legally broke away) from Sudan. As the existing state of Sudan did not contest this (removing the factor of internal competition) and no external competitor existed, South Sudan became the world’s newest nation-state in 2011.

There are territories often represented on maps which are described by terms such as ‘self- declared’ or ‘partially recognised’ because the two benchmarks of sovereignty are not yet fulfilled due to ongoing internal or external challenges. Among others, these include Taiwan, Kosovo and the Republic of Somaliland.

KEY TERMS: Diplomacy

Diplomacy is a process between actors (diplomats, usually representing a state) who exist within a system (international relations) and engage in private and public dialogue (diplomacy) to pursue their objectives in a peaceful manner. Diplomacy is part of the broader category of foreign policy. When a nation-state makes foreign policy, it does so for its own national interests. And these interests are shaped by a wide range of factors. In basic terms, a state’s foreign policy has two key ingredients: its actions and its strategies for achieving its goals. The interaction one state has with another is considered the act of its foreign policy. This act typically takes place via interactions between government personnel, sometimes the leaders of states themselves – as pictured in the image celebrating the Camp David Accords. Historically, to interact without diplomacy would limit a state’s foreign policy actions to conflict (usually war, but also economic sanctions) or espionage. In that sense, diplomacy is an essential tool required to operate successfully in today’s global system and a major explanatory factor that accounts for what Gaddis (1989) called the ‘long peace’ due to the absence of major war since 1945.

KEY TERMS: Polarity

The Cold War represented a global system of bipolarity. A bipolar system is one where two powers dominate. In that case, it was the United States on one side, and the Soviet Union on the other – with each side assembling their allies into their sphere of influence.

When the Cold War ended, a debate raged over how to describe the system. Some maintained that it was a system of unipolarity – as there was only one superpower remaining, the United States. This idea was captured by Krauthammer (1991) when he described it as a ‘unipolar moment’ in which the United States stood in an unprecedented historical situation where one state was significantly more economically, militarily and politically powerful to the extent that it would take a generation or more for a competitor of equal stature (a peer) to emerge.

Others have argued that the world has entered a period of multipolarity. Multipolarity is the historical norm as it describes a system with multiple competing powers. The last defined multipolar system ended shortly after the Second World War, which had left the European powers depleted – giving way to the Cold War bipolar system. Multipolarity today can be represented not just by rivalling states as it was in the past, but by the emergence of ideas of global governance through international organisations which compete with, and often constrain, the power of states.

Some suggest that bipolarity may return with the growing rivalry between the United States and a rising China shaping the twenty-first century. Others have suggested that a system of tripolarity may emerge, adding a resurgent Russia (or perhaps a different rising power) into the United States-China picture. While these perspectives draw on historical patterns for their inspiration, Acharya (2017) describes today’s system as one of multiplexity – a new type of order in which several systems exist independently at the same time, but not necessarily in conflict, much like the idea of different movies screening under one roof in a multiplex cinema.

END OF CHAPTER QUESTIONS

- In what ways has warfare been central to International Relations from its inception as a discipline?

- What is the ‘Westphalian system’ and why is it so important?

- With diplomacy, and the international organisations underpinning it, do we now have the tools we need to mitigate major war?

- What type of ‘polarity’ do you think best represents today’s global system?

- The post-Covid-19 era is hard to describe as it has only just begun, and we do not (yet) have the benefit of hindsight. Since you are living through it, what are your own impressions of it so far and how would you describe it?

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- International Relations Theory after the Cold War: China, the Global South and Non-state Actors

- Indonesia’s Role in International Relations: A Perspective from the Global South

- Fictional International Relations: Problematizing Fact and Fiction in Global Politics

- The Ethiopia Conflict in International Relations and Global Media Discourse

- Opinion – Dictatorships Are Unstable, Yet the International System Continues to Support Them

- Re-situating the Buffer State in International Relations: Nepal’s Relations with India and China