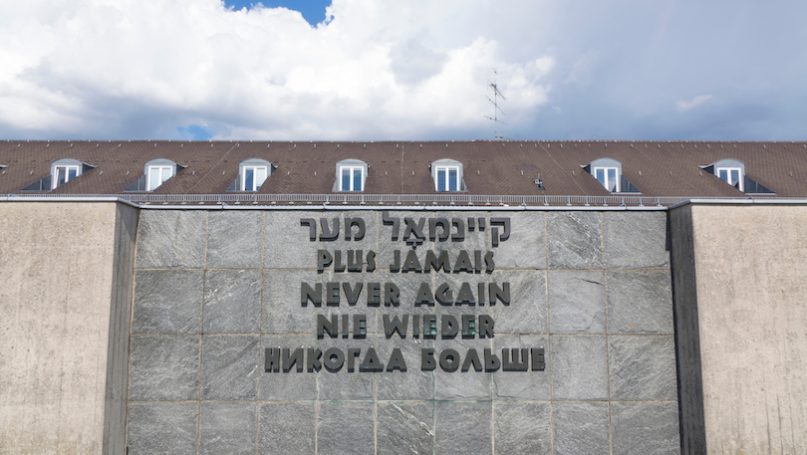

In July 2022, the U.S. State Department released the US Strategy to Anticipate, Prevent, and Respond to Atrocities, the U.S. Government’s first articulated national strategy on Atrocity Prevention. In October, the UK parliament’s international development select committee released a report that urged the UK government to form its own national strategy. Those working in atrocity prevention (AP) and trying to make “never again” a reality are cautiously supporting these steps on the part of these states to live up to their R2P.

R2P has been a state-centered doctrine since its inception. It calls on states to protect their own populations. When they fail in their protection, it calls on the international community to “encourage and help”, or to take collective action, usually military in nature, to protect those affected populations. This incarnation of the R2P doctrine has not been enough to prevent atrocities from continuing to take place around the world. It frames R2P as the task of actors, usually in the Global North, to save strangers, most often in the Global South, frequently through the use of arms. In addition to perpetuating racist and colonial logics of intervention, it also fails to acknowledge the role of civilian agency and non-military strategies in averting atrocity crimes. Instead of state-centric, strangers-saving-strangers R2P for atrocity prevention, we need to consider evolving the doctrine into civilian-led, “relational R2P”.

To further the evolution of R2P, atrocity prevention policies must center and support civil society and local populations as protection actors in their own right. Otherwise, states do not fully address the concerns of ineffectiveness and colonialism in the R2P doctrine as it exists today.

The U.S. government consulted with civil society in the formation of its national strategy, and the strategy mentions civil society and local actors, but a close reading reveals that their roles in implementing the strategy will be limited. “Locally Driven Solutions” headlines a section, in which “local” seems to refer only to local branches of U.S. government entities. The strategy states that the U.S. will “draw input from civil society” in its assessments of priority countries to target in atrocity prevention efforts, and in data collection and reflection, but actions like the development of response plans and implementation of strategies do not include any role for civil society, let alone for affected local populations. There is a gap where local civil society and local actors should be consulted in the development of responses. Even more glaring, is the lack of acknowledgment that local actors and civil society have a role to play in that response.

The U.K. parliamentary report, on the other hand, acknowledges that local actors and civil society have a role to play in the response to atrocity crimes. Yet that is not communicated as unequivocally as it could and ought to be. Expert witness testimony from international civil society representatives included in the report states that local civil society organizations and actors may be better placed for response and have a greater ability to offer alternative assistance than international actors, they have access to informal channels of communication to dissuade violence, and may possess useful prior experience delivering atrocity prevention programming.

These points, though included in the report, were not made explicit in the actual policy recommendations. Those stipulate an active role and simplified funding streams for civil society organisations, tying those to clauses about providing early warning of atrocity risks, which implicitly limits the interpretation of civil society’s capacity to that of early warning, especially to audiences who have not read the accompanying report and testimony. The policy, when it comes, must make clear that the active role for civil society is as a prevention and response actor in its own right, not only in aiding the U.K. early warning system.

All of the points addressing the capacities of local civil society and local actors were grouped in the report, misleadingly, under the section “Aid Programming”, which undercuts the attempt to acknowledge their expertise and resources. This needs to change with policy adoption to reflect and affirm that the U.K. government views local actors as equal partners in its atrocity prevention efforts – not just as beneficiaries.

Despite the laudable strides made in these national efforts, there is need for further recognition and support of more proactive roles for civil society and affected local populations. In this, the U.S. and U.K. can look to other national mechanisms that have been developed in recent years. Frank Oyerere Osei, a researcher at the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre, in speaking as part of an expert panel discussing the future of atrocity prevention, stated that in looking to where progress has been made in atrocity prevention, “civil society, in cooperation with state actors, are pushing the frontiers of prevention”. This includes in in national mechanisms that have been developed in several East African countries in which civil society representatives are members, not only consulted in the process of developing the mechanisms.

Osei also asserted that “atrocity prevention is more effective when you go down to the grassroots.” This is, in part, due to the relationships and knowledge that exists at that level. When local communities and civil society respond to atrocity crimes and risks, they are often able to access areas that many other actors cannot, and to respond with greater speed and agility. This has been demonstrated in Ukraine, where community-based groups, often including volunteer collectives, have been instrumental in evacuating civilians from areas under the threat of atrocity crimes. Relational strategies “are not blanket solutions”, and in the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, atrocity crimes have taken place despite the efforts of many. Still, to those civilians evacuated by the community-based groups, they “have meant that threats have been reduced, and lives saved.”

The UK report acknowledges that local communities have the close-up perspective and contextual knowledge to be able to analyze context and risks with greater depth and accuracy. In South Sudan, thousands of women have become members of Women’s Peacekeeping Teams, engaging in unarmed, protective accompaniment and presence, sometimes alongside INGOs like Nonviolent Peaceforce, forming Early Warning Early Response Networks, and conducting highly specific and dynamic risk analyses. These locally-led networks not only flag the warning signs, but take action on their own in community self-protection – a role that should be supported, not simply tapped to feed into outside government responses.

The engagement of civil society and affected local actors in unarmed civilian protection, particularly community self-protection strategies, is too important and effective a tool in atrocity prevention to leave it out of consideration. Explicitly acknowledging civil society and local actors’ role in response and protection is key to propagating that tool.

Locally-led efforts often need legitimacy and resources. National governments, as part of their atrocity prevention strategies, can fund more unarmed, civilian-led efforts to prevent and respond to atrocities, such as funding the type of volunteer-collective led unarmed efforts that have been saving lives in Ukraine. The U.S. Government can do so by passing the Fiscal Year 2023 spending package, which includes language that directs funds be provided for unarmed civilian protection programs. For Fiscal Year 2024 the U.S. government can fund the State Department’s Atrocity Prevention fund at $25 million and allocate $25 million to unarmed civilian protection.

The UK government can enact the ambitious national atrocity prevention strategy its report calls for, clarifying its take on the role of civil society and local actors, and back that up with aid spending that supports atrocity prevention. This would course correct from an “overall reduction to the UK aid budget in recent years [that is] likely to have affected programmes relating to atrocity prevention,” as the report notes. Civil society and local actors already play a protective and responsive role in atrocity prevention, leading the way in relational R2P. Let’s see the U.S. and U.K. clearly recognize and support those efforts in their national strategies and spending.

*This article is informed by Nonviolent Peaceforce’s unarmed civilian protection work around the world and builds on Felicity Gray’s recent paper, Relational R2P? Civilian-Led Prevention and Protection against Atrocity Crimes.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – UK Militarism Can (and Must) Be Resisted

- Humanitarian Intervention: Alive and Kicking

- The Responsibility to Protect in 2020: Thinking Beyond the UN Security Council

- Opinion – Britain and the American South: A Special Relationship?

- Opinion – Breaking Free From the Special Relationship

- Opinion – The Responsibility to Protect the Amazon