Volunteer abroad programmes have become an increasingly popular option for young people over the last two decades (Toomey, 2017), building on and adapting the long tradition of missionary workers and development workers. In this article, I will assess this phenomenon and reflect on the legacy of colonial projects and civilising missions today. A postcolonial perspective will be used to build on research focusing on the tendency of Western-led volunteer abroad programmes to work within and even further contribute to neo-colonial ideas of the Global South. Within this article, I also utilise my personal experience as a former volunteer on the International Citizen Service (ICS) programme in 2018. I, like many others, had not fully considered my place as a young, white, and inexperienced volunteer in Kenya before applying; therefore, this article serves as my reflections on volunteering abroad with the knowledge, experience and insights I have gained over the years since.

ICS was a volunteer development programme that sent 18–25-year-old British citizens to communities in the Global South and claimed to work towards aims such as ‘reducing poverty and tackling global challenges’ (ICSa, n.d.). As a development programme with the general aim of ‘tackling global challenges’, the postcolonial theory would suggest that the history and legacy of colonialism are crucial considerations, as neo-colonialism remains a global challenge and a great barrier to global equality (Hodges, 1972, p. 12). Therefore, the role ICS plays in creating, addressing and challenging colonial legacies and global power dynamics has important implications on the impact the programme can have (Toomey, 2017). Throughout the article, postcolonial literature and perspectives are used to provide context, understanding and analysis of the findings presented.

Literature Review

Colonialism, decolonisation, and neo-colonialism

The continent of Africa has been colonised by numerous civilisations throughout history, but when we speak of and research the colonisation of Africa today, we think primarily of colonisation by European powers. Colonialism, broadly defined, is the coercive relationship between a subordinate state and a ‘foreign power’ (Martin, 1982, p. 224), in which the foreign power holds economic, policy, social and cultural (among others) control over the subordinate state (Faleiro, 2013, p. 13). Africa can now ‘claim to be technically ‘postcolonial’’ (Young, 2016, p. 3) as it has gone through a process of ‘decolonisation’, with formal colonial control withdrawn between the 1920s to 1975. But decolonialisation did not mark a total break from the power and control over former colonies by the colonising powers, resulting in a state of ‘neo-colonialism’. Young (2016) describes neo-colonialism as the continued creation of conditions for postcolonial states to depend on their ‘former masters’ and the continuation of ‘former masters’ to act in a ‘colonialist manner’ towards the postcolonial states (p. 45). Many academics speak of neo-colonialism in terms of economic and policy control (Klay Kieh, 2009; Martin, 1982); however, postcolonial scholars such as Walter Rodney explain that it is essential to consider different methods of neo-colonial control over African countries that bring non-monetary benefits to the former colonising countries (Rodney, 1981, p. 185).

Colonial power constructs

There is an abundance of postcolonial theorists deconstructing and analysing the effects of colonialism on the contemporary world. Young (2016) explains that postcolonial theory aims to politically analyse and criticise the ‘conditions of postcoloniality’ (p. 58). Loomba (2015) claims that although there is much debate over the validity of postcolonial studies, what it does successfully is shed light on the ‘history and legacy of European imperialism’. One crucial reflection in postcolonial literature on the process of colonialism is the power discourses it creates around Whiteness and the colonial ‘Other’. Over centuries, colonialism has worked to construct the idea and practice of eurocentrism on a global scale, imposing what Gabay (2018), among others, calls ‘Whiteness’ (p. 13) onto the colonial ‘Other’. Interestingly, Gabay explains in Imaging Africa that the mutability of this construct of Whiteness is often forgotten in postcolonial work and should be understood as a series of logics that control and structure all aspects of life rather than being a description of a certain skin colour (Gabay, 2018, p. 14). This ranges from structuring beliefs, attitudes, spaces, behaviours and much more (Gabay, 2018, p. 14). With this definition, the process of constructing the logic of Whiteness can be found in the foundations of colonialism and has become entrenched in such a way that Whiteness still has a grip on what we consider to be the ‘normal’ and ‘moral standard’ today. This is potentially one of the most powerful immaterial legacies of colonialism, as many postcolonial scholars show that conforming to and imposing Whiteness has wide and deep implications that motivate much of the behaviour in the field of development and volunteering.

Throughout colonialism, practices and discourses have served to ‘abnormalise’ (Gabay, 2018, p.14) people who do not conform to the structures of Whiteness. Elliot-Cooper (2021) supports Gabay’s theory by recalling how the British abnormalised African religious, social and spiritual systems by labelling them a result of ‘psychosis’ and fighting them with ‘White’ values and education (p. 146). Through decades of abnormalisation of ‘non-European’ behaviours and practices, colonialism built up a strong defence of the supremacy of eurocentrism and the idea that the West were the original ‘pioneers of development’ (Gabay, 2018, p. 12). In constructing Whiteness as the norm, colonialists were able to speak of colonialism as a ‘civilising mission’ because Whiteness was associated with all that was positive – civilisation, development, intelligence – therefore, anyone who did not conform to Whiteness was uncivilised (Rodney, 1981, p. 186). By using this discourse of logic, imposing the presence and interference of Europeans onto the colonised could be justified as a positive process in the interests of the welfare of the ‘uncivilised natives’ (Rodney, 1981, p. 186).

Exploits of colonialism

Many scholars, when writing about the motivations and benefits of colonisation, place a heavy focus on the monetary benefits of exploitation (Martin, 1982, p. 227) and talk of this relationship in terms of ‘economic exploitation through the control of colonial resources’ (Faleiro, 2013, p. 13). However, while certainly an important dimension of colonialism, in order to fully understand neo-colonial relations today, we must understand colonialism beyond economic gain. The non-monetary benefits of colonialism can be seen everywhere: European powers leached on African social and cultural capital, stealing artefacts, practices, hairstyles, and cuisines (plus more). Britain then claimed these as their own (Heldke, 2001, p. 77), which only served to enrich the lives of Westerners. Look to the British Museum, a memorial to British colonialism, with hundreds of stolen artefacts from all over the globe on display (Rodney, 1981, p. 186). The British Museum symbolises the colonial construction of the idea of a ‘civilised’ and ‘developed’ Britain (Rodney, 1981, p. 186), in contrast to colonised populations.

What this non-monetary gain from colonisation also shows is that colonialism was also about an attitude and feeling of superiority that Europeans gained from the exploitation of the colonies. This white European superiority complex was partly developed and justified by the underdevelopment of the colonies and the creation of a racialised ‘Other’. An essential area of underdevelopment created by the British was under-education in Africa. Rodney explains that in Kenya, white colonisers actively discouraged and prevented the education of the native Kenyan population because they were easier to control and put to manual labour than educated Kenyans (Rodney, 1981, p. 265). British colonialists needed to maintain an advantage over the colonised population in order to maintain control and the feeling of superiority, so when the Mau Mau war for liberation happened in Kenya between 1952 to 1960, the British government destroyed 149 schools built by the Kikuyu Independent Schools Association, claiming that schools were ‘training grounds for rebellion’ (Rodney, 1981, p. 271). The weaponization of education as a tool for the underdevelopment of Africa is one important aspect of colonialism as it contributed to the idea of white superiority and justified control over policies and labour in Africa – how could uneducated and uncivilised populations govern themselves?

Neo-colonialism and volunteer abroad programmes

When considering the legacy of colonialism in a mostly decolonised world, one key aspect of research in postcolonial studies is looking at ways in which the unequal power dynamics between the Global North and Global South are rearticulated and practised today, evidencing the existence of neo-colonialism (Raymond & Hall, 2008). By doing so, postcolonial scholars are shedding light on one of the major ways in which British aid to Africa reinforces neo-colonial relations, and this article will contribute to this literature with a focus on British youth volunteering in Kenya. Griffiths explains that much of the aid and volunteer programmes created by the British both play on the unequal power relations created by colonialism and have a tendency to ‘write out critical perspectives’ on development and aid, which has the effect of depoliticising and dehistoricising the causes of the inequality they claim to tackle (Griffiths, 2017, p. 413). As Gabay (2018) has described, what effect this dehistoricised and depoliticised approach to inequality and poverty have is to maintain the ‘centrality of White logics’ to the management of all aspects of life (p. 120), including the idea that the West is the ‘original pioneer of development’ (p. 12). In examining the neo-colonial practices of the British Department for International Development (DfID), Ballie Smith and Laurie (2011) find that DfID promotes ideas of ‘citizenship and professional development’ in global development without any consideration of what role this plays in a postcolonial context and how it dismisses the colonial history of British aid (p. 553). Furthermore, according to Griffith (2017), DfID marginalises power relations and frames poverty as ‘spontaneously occurring’, which excludes critical perspectives of inequality as a product of structural processes and unequal power relations which find their roots in colonialism (pp. 339, 406).

To Toomey (2017), the tendency of many volunteer organisations to prioritise the interests of the volunteer over the needs of the communities they volunteer in reproduces the concept of Whiteness and a ‘colonial approach to the Other’ (p. 166). By neglecting the experience of the communities and poorly training under-experienced volunteers (Toomey, 2017, p. 164), which Raymond et al. (2008) describe as volunteer tourists inappropriately assuming the role of ‘expert’ or ‘teacher’, it reinforces the ‘neo-colonial construction’ of the European volunteer as being superior (p. 531). By sending unprepared volunteers to communities in the Global South to supposedly add value, it sends a message that it is acceptable to use these communities as ‘training grounds’ for Europeans to personally and professionally develop (Raymond & Hall, 2008, p. 539). This harkens back to Rodney’s (1981) critique of colonialism as not just an economically exploitative process but one of social and cultural exploitation (p. 186), which Toomey and Raymond et al. demonstrate takes a neo-colonial form in the exploitation of the Global South as a space for European volunteers to enrich their lives. This critique is supported by Hickel (2013), who describes the dynamic of short-term volunteer programmes, explaining that the volunteer can be seen as the ‘consumer’ while the host community is the ‘raw material’ used to create the product, which in this case is the ‘self-development’ of the volunteer (p. 21). I will draw on this literature to analyse the Voluntary Services Overseas (VSO) run volunteer programme ICS from a postcolonial perspective.

Methodology

As this article is inspired and based on my own personal experience as a British volunteer in Kenya, it can be partly described as an autoethnography. Autoethnography focuses on research into the self and culture, using experience as both a ‘source of knowledge’ and a topic to be made sense of and analysed for meaning (Bell et al., 2019, p. 850). As such, I tell my story and the story of fellow volunteers on the ICS programme, as both British volunteers and Kenyan volunteers on a British volunteer programme. As part of an autoethnography, it was vital for me to question my right to speak on this topic and consider who I was speaking for (Edwards, 2021, p. 3). Therefore, I want to clarify that this article focuses mainly on the experience of outsiders of a culture and country (me and my fellow British volunteers) and how this dynamic can be analysed in a postcolonial context. As such, I do not claim to speak for the populations we encountered and worked with in Kenya and instead emphasise the importance of further research and considerations of their experience from their own perspective. Furthermore, my sample size was small and, thus, is not representative of the British or Kenyan volunteer’s experiences as a whole. Still, I use these interviews to help illustrate a set of dynamics I wish to critique within the volunteer programme.

To provide a more cohesive and meaningful autoethnography, I interviewed seven fellow volunteers. I did not just want my interviewees to ‘help with recall’ (Ellis et al., 2011, p. 275), but I also wanted the opportunity to include other perspectives and experiences in my analysis of the volunteer programme. I conducted interviews in the form of what Garton and Copland(2010) call ‘acquaintance interviews’ (p. 536) with former volunteers on the same ICS programme as me. I chose to interview both British volunteers and Kenyan volunteers who participated in the programme in order to provide multiple perspectives from people who both arrived as outsiders of the cultural and political sphere we volunteered in and those who belonged to it. I conducted the interviews over a video conference platform of the interviewees’ choice and recorded the audio to be transcribed onto a word document. Each interview lasted around one hour and was semi-structured, with a set list of questions but flexibility for follow-up questions and different anecdotes and perspectives to be explored. Transcribed data was then organised and analysed thematically (Paul Gee, 2010, p. 8). I conducted a discourse and narrative analysis, extrapolating meanings and findings from our conversations.

I should also add that I requested an interview with VSO representatives to discuss the selection and training process for ICS volunteers, how they had factored sustainability into their programmes and the history of the programme. I wanted to do this to ensure I would not be making assumptions and speaking on behalf of the organisation, instead allowing them to present and explain themselves. However, VSO declined my request stating limited resources. Therefore, my research into ICS was limited to net-archival research such as blogs, advertisements and reports published by the organisation. I conducted both content, and discourse analysis on these resources to both discover facts about the programme and also how and why they presented themselves in the way they did. Not being able to interview representatives presents the risk of a lack of nuance and misrepresentation of ICS. However, I have ensured to present as many personal accounts of the programme as possible to create a fuller picture, which I cross-reference and contrast with the experience of the volunteers I interviewed and my own.

International Citizen Service

In this section, I will analyse ICS. Postcolonial and development literature will be used to analyse and critique the narrative created by ICS, with a focus on their marketing, presentation and explanation of poverty and inequality and how they attempt to set themselves apart from what they believe to be unsustainable ‘voluntourism’ programmes.

Background

International Citizen Service was a volunteer programme that provided British 18–25-year-olds with the opportunity to volunteer ‘in some of the poorest communities in Africa and Asia’ (ICSa, n.d.). The programme was run by three development organisations, with VSO being the lead partner. Beginning in 2011, ICS came to its planned end in December 2020 (VSOa, n.d.). VSO began in 1958 when 16 British volunteers were recruited to teach English voluntarily in Borneo in response to the Bishop of Portsmouth’s request (VSOb, n.d.). Since then, they have built a reputation as a volunteer organisation that utilises the skills and professions of a variety of volunteers, with an emphasis in their advertising on recruiting ‘experienced professionals’ (VSOc, n.d.). VSO has made attempts to distance itself from its colonial missionary history by building positive, anti-colonial relations with partners in the Global South. It is on this basis that I analyse their volunteer programme, ICS. VSO is funded by a variety of sources, with 49% of funding in 2020-2021 provided by institutional grants. £16 million of this was made up of governmental incomes, including Global Affairs Canada, the European Union and United Nations agencies (VSO, 2021, p. 37). £8 million was donated by non-governmental bodies such as Mastercard Foundation, Hempel Foundation and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (VSO, 2021). The ICS programme itself was 90% funded by the UK government, while volunteers fundraised the remaining 10% (ICS, 2020).

How was ICS marketed?

ICS claims their projects aimed to ‘increase the economic opportunities and self-sufficiency of communities’ (ICS, 2020). They also championed education projects – including the one I volunteered on – explaining that they aimed to ‘improve access to education among disadvantaged groups in rural communities’ (ICS, 2020). Former UK Prime Minister David Cameron, in promoting the ICS programme, explained how the experience allowed young people to ‘do something positive to help’ (DfID & Mitchell, 2012). However, this was a footnote in a speech mainly promoting the advantages the programme would have on volunteers, including how it would provide them with a chance ‘to really understand the many challenges faced by people from very poor countries’ (DfID & Mitchell, 2012). This is in line with the DfID marketing of ICS, which focused heavily on the programme as an opportunity for self-development, to ‘broaden the horizons of young adults and develop key skills’ and ‘build the confidence necessary to achieve their personal and professional goals in later life’ (DfID & Mitchell, 2012).

A pattern begins to emerge, with any attempt by ICS to consider the programme’s impact on local communities and global development left unexpanded and overshadowed by a strong focus on how the programme has benefitted the British volunteers. The 2012-2020 report claims that 77% of ICS volunteers identified ‘personal development’ in their top three achievements, and 74% reported the experience as ‘very useful’ for their career development (ICS, 2020). While not intrinsically bad to value self-development, the heavy focus in reports and advertisements of the programme on the benefits to the volunteers suggests that within the ICS programme, the self-development of the young volunteers is actually put before development itself (Hickel, 2013, p. 21). But whether it is true or not that creating active ‘international citizens’ is the main aim of ICS, when the volunteer is the priority in a volunteer abroad programme, it is possible to conclude that inequality and the opportunity to ‘tackle it’ has become a ‘commodity itself’ (Hickel, 2013, p. 21). As such, it appears that, based on their own material, ICS was promoting the use of ‘developing countries’ as ‘training grounds’ for young volunteers’ professional futures (Raymond & Hall, 2008, p. 539). This distracts from the needs of the community and the ‘structural causes of oppression’ (Toomey, 2017, p. 167) and instead reproduces processes of exploitation seen during colonialism (Rodney, 1981), which I explore in the next section.

How was inequality addressed and framed by ICS?

How ICS addressed and framed inequality can tell us a lot about their relationship to neo-colonialism. According to Griffiths’ research and his former ICS volunteer interviewees, educational sessions on development were provided by ICS to volunteers but it drew ‘heavily’ on UN and DfID material (Griffiths, 2017, p. 401), such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals. These governmental bodies largely engage in an apolitical and uncritical analysis of poverty and inequality. Thus, Griffiths finds it unsurprising that ICS education on development lacked critical and historical perspectives. The significance of the relationship between ICS and the UK Government when analysing how seriously VSO and ICS take the history of colonialism and underdevelopment should not be underestimated. In 2011, Prime Minister David Cameron spoke about the importance of the aid budget for international development:

Meeting our international aid commitments is profoundly in our own national interest. If we invest in countries before they become broken, we might not end up spending so much on the problems that result… So it is in our national interest not just to deal with the symptoms of conflict when they arise, but also to prevent that conflict by addressing the underlying causes – poverty, disease and lack of opportunity.

(Cameron, 2011)

This statement reveals much about the attitude of the government towards development and countries in the Global South. The discourse created around these subjects by Cameron, including the idea that a country can be ‘broken’ and that contributing to aid is ‘in our national interest’, implies that developing countries in the Global South are fundamentally burdensome and in need of ‘fixing’. Poverty and disease are not issues to address alone but only become Britain’s problem when they cause conflict. Speaking of poverty and disease as a ‘symptom of conflict’ feeds into what Toomey (2017) describes as a ‘practice of depoliticised managerialism’ (p. 164), which Cameron removes from the discourse of Britain’s long history of colonialism and exploitation of countries in the Global South, and contemporary political relations that result from this.

In a search for acknowledgement of the concepts of colonialism, global power structures or racism from ICS on their website, only a webpage entitled ‘Our approach to anti-racism’ (ICSc, n.d.) can be found. In this publication, ICS talks about the importance of cross-cultural relationships both in achieving ‘great positive outcomes’ and also having the potential to perpetuate negative dynamics (ICSc, n.d.). Perhaps this alludes to the construction of negative perceptions and relationships with the Global South by the Global North, but ICS does not expand this idea. While diversity is undoubtedly an important part of the struggle against neo-colonialism, focusing on the impact diversity has on volunteers is to the detriment of local communities. It would therefore be very difficult to claim that ICS as a volunteer development programme meaningfully considered its impact on the neo-colonial relations between the Global North and Global South if its training, publications and critical funding institution (the UK Government) fail to engage with the very concepts of colonialism, exploitation and capitalism. Without engaging with the colonial history of aid as a ‘civilising’ and ‘Othering’ mission or the ‘capitalist structure’ that thrives on inequality (Toomey, 2017, pp. 161, 166), ICS considerably limited its ability to tackle global inequality, stereotypes, and racism.

ICS on organisation, structure and sustainability

ICS claims that all their projects were based around the ‘needs, priorities and aspirations of the communities’ and were collaboratively delivered with the community, ‘with sustainability in mind’ (ICS, 2020). In their 2011-2020 report and a blog entitled ‘Responsible volunteering’, ICS discussed the importance of being aware of and avoiding ‘poorly-managed projects’ which ‘inadvertently do more harm than good’ (ICSb, n.d.). To raise awareness of damaging volunteer opportunities, ICS provided a ‘Responsible Volunteering Checklist’ which asks questions such as: does the organisation work with local partners? And, do they provide training before you go? (ICSb, n.d.). Interestingly, this checklist has been curated in such a way that ICS could check all the boxes and thus claim to be a responsible volunteer programme based on its own criteria. It is true that ICS volunteers did receive some form of training before they travelled, and they also worked with local partners such as the local VTCs and local businesses. However, this criterion does not fully engage with the quality, purpose or scope of these factors and thus may be misleading. Furthermore, if this checklist is representative of what ICS considered to be ‘responsible volunteering’, I do not believe they held themselves to a very high or dynamic standard, which will be explored further.

ICS claims that impactful volunteer projects work because the design enables volunteers to ‘add real value’ instead of ‘engaging in superficial… work’ (ICSb, n.d.). Engaging in superficial work is harmful for many reasons, including reinforcement of the idea that it is acceptable to use the Global South as space to become ‘spectators’ to poverty with no critical engagement or resolution building (Toomey, 2017). ICS warns against projects that provide volunteers with work they are unqualified and unprepared for (ICSb, n.d.). This suggests that ICS believe they chose volunteers who were suitably qualified and prepared for a volunteer role. However, in another publication, they claim that in youth volunteering, ‘technical skills like carpentry or business management’ do not matter (Taylor, 2019). Instead, it is only qualities such as ‘enthusiasm’, ‘commitment’, ‘energy’ and ‘passion’ that are needed to make a ‘substantial difference to individuals in the poorest and most marginalised communities’ (Taylor, 2019). This blatant contradiction demonstrates that ICS did not consider the wider implications of volunteer selection criteria and raises a range of questions and issues, such as how it is possible that young British volunteers with ‘enthusiasm’ and ‘energy’ but no practical skills have any transformative effect on local communities in the Global South (Toomey, 2017), and what qualifies them to work on problems within communities they have never encountered before.

An ICS project with a positive impact

In an effort not to engage in confirmation bias by presenting a narrow view of ICS, I would like to highlight an ICS project I encountered in my research that appeared to address some of the fundamental issues I have raised about ICS so far. In 2016, a group of British deaf ICS volunteers worked in Kenya to support local deaf people (Mezbourian, 2017). ICS selected volunteers for this project based on their personal experience as people with deafness who had diverse working backgrounds, such as engineers and psychologists (Mezbourian, 2017). As such, the volunteers were able to utilise their experience and sign language skills to teach 450 community members sign language, address the stigma surrounding deafness in the community, and provide advice to the families of deaf children (Mezbourian, 2017). With this ICS project, a clear need in the community was identified, the skills necessary to carry out the project could not be found among community members, and therefore volunteers were selected based on their ability to fulfil this need. A transfer of skills took place, which provided the community with the skills to continue teaching and benefitting from the project in the British volunteer’s absence, which removes the neo-colonial characteristic of forced dependency on former colonisers.

It is possible that the specialised nature and future sustainability of this ICS project challenged the common issue of British volunteers reinforcing people’s ‘sense of relative poverty and marginality… resigned to roles as aid-recipients’ (Garland, 2012). British volunteers were ‘appropriately qualified’ and thus hopefully able to make ‘genuine contribution’ (Raymond & Hall, 2008, p. 539) instead of patronising the community with their lack of experience and skills. While I believe this reflection is important, I do not intend to present this as an example of the perfect volunteer abroad project. ICS has shaped available knowledge about the project in their own publication, meaning I could not learn about the training the volunteers received in terms of training, both practical and educational on inequalities. Therefore, in the next section, I will analyse one specific ICS cycle that took place in 2018 in the Taita-Taveta district of Kenya from the perspective of seven volunteers who are no longer affiliated with ICS.

Former Volunteer Perspectives

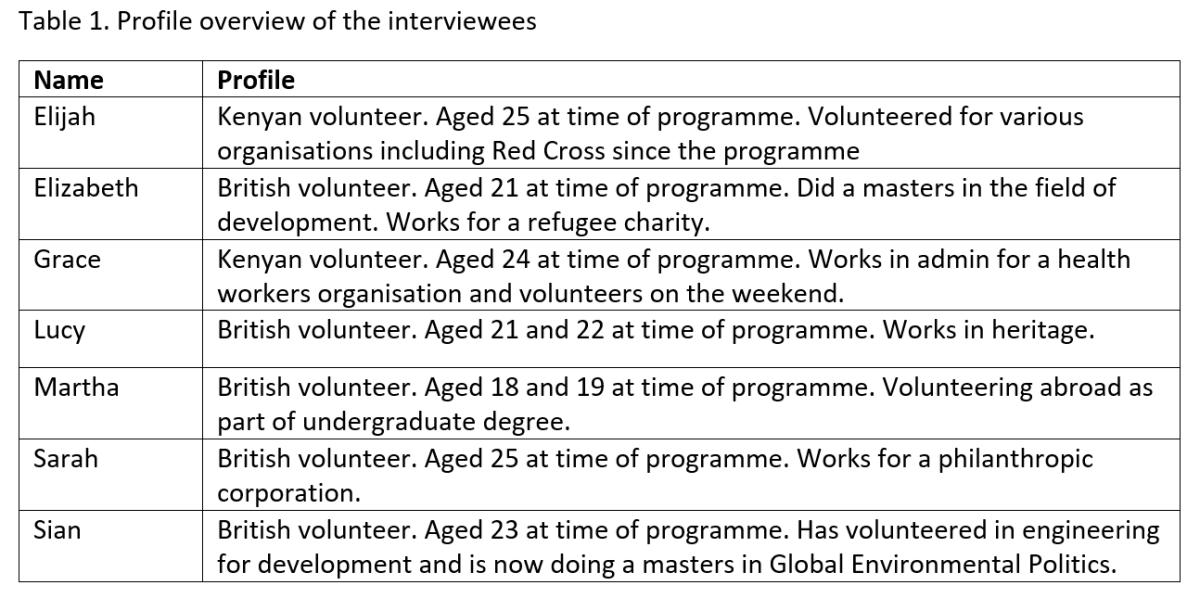

In this section, the results of my volunteer interviews will be categorised based on themes and analysed through a postcolonial lens. Opinions, information, and critiques offered by the volunteers will be discussed for meaning. Following on from the previous section, this section also uses the experiences of the volunteers as a response and critique of the information and claims provided by ICS to assess further their practical application and implications based on one real ICS programme. The names of all my interviewees have been changed for anonymity (see Table 1. Profile overview of the interviewees).

Motivation to volunteer with ICS

Firstly, I asked my interviewees what motivated them to apply for volunteering with ICS. For the most part, all the volunteers responded with similar sentiments: a desire to volunteer to make a positive change. When asked more specifically why they chose ICS for this experience, Elizabeth, 21 at the time of the volunteer programme, told me that she had learnt about unsustainable volunteer practices on her degree course and thus wanted to choose a programme that was sustainable and ethical. She told me she ‘trusted the UK government’ and that it was a ‘known scheme’ which gave it ‘credibility’ (Elizabeth, 2022). Sarah, aged 25 on the programme, wanted to take a sabbatical that would help develop her interest in global health and development in a sustainable way. She wanted to ensure she ‘wouldn’t cause harm’ and could work on something ‘useful and relevant’ to her ‘skillset’ (Sarah, 2022). She believed she had found that in ICS, based on their marketing and the interview process. In an ICS publication, they claimed not to ‘put volunteers into contexts they are unqualified and underprepared for’ (ICSc, n.d.). It was claims like this that reassured the volunteers that the programme would not be like the ‘voluntourism’ experiences they wanted to avoid. Several interviewees talked about their growing interest in a career in development as a motivating factor for volunteers.

Sian, a British volunteer aged 23 on the programme, wanted to get into the field professionally and gain as much volunteer experience as possible (Sian, 2022). This demonstrates that many of the volunteers, myself included, felt that volunteering abroad with ICS was a crucial and appropriate step in gaining the experience and insight needed to achieve our professional goals, based on what we had learnt from others and the way that ICS was marketed to us. This is a common belief and practice within the ‘volunteer gap year’, in which young people, even with the best intentions, use the Global South as a space for their own development (Garland, 2012; Hickel, 2013).

Selection criteria for ICS

One important way to assess the purpose and responsibility of a volunteer programme is by examining the ICS selection criteria. As previously highlighted, ICS claims they select work for volunteers based on their qualifications and capabilities (ICSb, n.d.) while also claiming that technical skills are not important (Taylor, 2019). So, while we have established that ICS does not value technical skills, I wanted to know whether, given the skills and qualities the volunteers possessed, they felt qualified to volunteer in an unknown community with specialised needs. The volunteers were able to answer this with hindsight, reflecting on the activities they were assigned and their ability to carry out these activities. Elizabeth, aged 21 on the programme, who was tasked with training and supporting small businesses, told me that she felt at the time that her anthropology degree meant she had ‘absolutely no business advising anybody’ and so she felt superfluous.

Grace, a Kenyan volunteer who was 24 on the programme, felt that her age and previous volunteer experience gave her an advantage because she was able to understand and ‘pass on information’ she had learnt about business growth from the training. However, she felt that having never had a business herself limited the effectiveness of the workshops. Lucy, a British volunteer aged 21 on the programme, when asked about what skills she thought ICS sought in volunteers, felt that ICS did not seem to turn many applicants down and she did not get the impression that they sought any skills or qualifications in the applicants.

I argue that taking on roles they were not qualified to do simply because they were given the power to do so by a British volunteer organisation reasserts the ‘neo-colonial construction of the westerner as racially and culturally superior’ (Raymond & Hall, 2008, p. 531). My enquiry into the skills and qualifications of the volunteers compared to their placements demonstrated that they felt qualities ICS valued over technical skills, such as ‘enthusiasm’, ‘passion’ and ‘commitment’ (Taylor, 2019) alone were not conducive to the most effective, responsible and worthwhile volunteering that could contribute towards challenges to global power imbalances.

Training on ICS

According to ICS, the fact that they provide ‘training before you go’ (ICSb, n.d.) qualifies them as a responsible volunteering programme. However, exactly what content the training involves has important implications for the impact the programme has on the local community and on the neo-colonial relationship between Britain and Kenya. First, I explored whether volunteers received practical training to fulfil their placements better. Sarah, aged 25, remembers that training in the UK was more focused on safeguarding and the potential challenges we could encounter in a new culture (Sarah, 2022). While Sarah found this somewhat helpful, Lucy echoed the general feelings of the volunteers, explaining that training in the UK did not prepare her for what was actually expected. Elijah, a Kenyan volunteer aged 25 on the programme, said he did not receive specific training on the placements he was tasked with (Elijah, 2022).

Furthermore, given the consensus in much postcolonial literature on the danger of volunteer abroad programmes to perpetuate neo-colonial power relations and dependencies (Raymond & Hall, 2008; Hickel, 2013), one of the most important criteria for me in assessing the ICS programmes’ place in this discourse was the level of attention and acknowledgement they paid to Britain’s colonial past and the role it has played in global inequalities. Many volunteers worked in polytechnics, addressing the ‘underdevelopment’ of education in Kenya. An important example already highlighted by Rodney was the destruction of education systems in Kenya by the British. This was a colonial project designed to control Indigenous populations (Rodney, 1981). Only when this is known and understood can anyone, including UK volunteers, begin to address contemporary struggles for education with the respect and resolutions necessary.

As discovered in the previous section, the partnership with the UK Government seemed to affect the level of engagement ICS had with these issues, and the volunteers appeared to confirm what I found in my net-archival research. Few volunteers could recall what ICS disseminated in training about global inequality and development. From my experience, supported by the interviews Griffiths (2017) conducted with other former ICS volunteers, there was a sole focus on the UN Sustainable Development Goals such as ‘quality education’ and ‘clean water and sanitation’ (UN, n.d), which they drew from create and justify the focus and design of our projects. For ICS, these served as explanations and solutions for inequality, and any further analysis of inequality and global power structures was left out, let alone a discussion about colonialism. Elizabeth agreed, commenting that there was no encouragement to think critically about inequality or aid (Elizabeth, 2022). In her work on volunteer tourism, Simpson (2004) highlights that any educative process that leaves out these important dynamics of inequality ‘becomes complicit with them’ (p. 690), which is the least desirable quality of a volunteer development programme.

Organisation and sustainability of the programme

In their publication outlining what they believe to be ‘responsible volunteering’, ICS claimed that the design of their programmes prevented volunteers from ‘engaging in superficial… work’ (ICSb, n.d.). To test the ICS claim, I asked the volunteers about the structure and organisation of their placements. The volunteers unanimously agreed that the placements they worked on were poorly organised and did not have the level of the positive impact they were expecting. Martha, who was on teaching placement in a local polytechnic school, explained that they were timetabled to teach at polytechnics despite them being closed for weeks for holidays. Overwhelmingly, Martha and her fellow volunteer felt they were not needed because the schools already had qualified teachers.

The idea that placement was provided for the sake of the experience rather than successfully filling a genuine need was echoed by Elizabeth, who taught in polytechnics and provided training to small businesses. In the business workshops, she found it hard to contribute because much of it was conducted in Kiswahili, not English. Sarah worked with the Kenya Red Cross alongside me, and we reminisced about the lack of structure and ad hoc nature of the placement. Sarah did not feel like there was any continuity to our work from week to week, and neither of us had the skills to ‘really make a difference in that setting’. On reflection, Sarah said, ‘thinking about it years later, I got more out of it than the community got out of it’. The combination of working on placements with skilled staff already filling positions, poor organisation and lack of skill-matching perpetuate the idea that development simply requires passion and willingness of volunteers (Simpson, 2004). Without meaningful consideration of the impact this had on local communities, we can see the experience of the volunteer being prioritised again (Toomey, 2017).

Experience of white volunteers in Kenya

During the interviews, the Whiteness of the volunteers was discussed by all who could relate as an important point of discomfort. The dynamic was unique in that the discomfort arose from the unique treatment that seemed to put us in higher regard and respect because of our Whiteness. Elizabeth recalled that most of the positions she was placed in, such as advising small businesses at workshops, were by merit of being ‘white’ rather than skills or experience. Martha also spoke about her experience as an inexperienced white volunteer, commenting that she appeared to receive a unique level of trust and expectations compared to other. This is despite the fact that she recognised her Kenyan counterpart volunteers as more experienced and capable, given their level of education and ability to relate to the culture and practices of the community more easily. Lucy recalled being told by her Kenyan counterpart volunteer that being white meant they could get more done and faster because people will take her more seriously.

What her counterpart was telling her was not a fabrication; it resonated well with my experiences on placement. As one of the only white volunteers with the local Red Cross, my Whiteness was utilised and revered in a way I had not before anticipated. I stood front and centre for photos of rural villages I have never encountered before, celebrating their achievements. I was asked to pose as a project coordinator for housing projects because the volunteers believed the local participants would take me more seriously and be inspired to work harder in my presence. Given that I was not qualified or able to take credit for any of these things, it seems as though being white in Kenya is valuable on its own. With all this in mind, it is hard not to argue that the structure, practices and lack of historical, political and social awareness or acknowledgement within the ICS programme serve to reproduce colonial relations and unequal power structures between the Global North and South.

Did the volunteers feel the programme challenged or engrained power dynamics?

In this section, I analyse the issues of Whiteness, colonialism and power from the perspective of the Kenyan ICS volunteers. Unfortunately, I could only interview two Kenyan volunteers, so this perspective is limited. Elijah, a Kenyan volunteer on the programme, was 25 at the time. From the beginning of my interview with Elijah, I got the impression that he was not overly critical of the ICS programme in terms of British volunteers entering a new community and assuming roles such as teachers and business advisors. Elijah believed the opportunity to ‘combine the British and Kenyan volunteers was a great opportunity for development’, and he enjoyed the opportunity to work and socialise with British volunteers. It was interesting to discover that an educated Kenyan, who had engaged with ICS, believed collaboration with British volunteers in Kenya was beneficial to development. Elijah elaborated, saying: ‘in terms of development, you are more developed than us’, which explained why we were given the privilege of travelling to Kenya. As our interview developed, I sensed Elijah reflecting and becoming more aware of the implications of this belief and how it manifested in the ICS programme. According to Elijah, there is an idea in Kenya that white people are ‘more skilled and have more professionalism’, but his time spent with the British volunteers demonstrated that this perception ‘isn’t always true’.

Grace, a Kenyan volunteer aged 25 on the programme, supported Elijah’s reflections, explaining that there was a suggestion of superiority that Whiteness carried, which was reconstructed both by the British team travelling far to volunteer in Kenya and the way in which the British volunteers were framed to the Kenyan volunteers in their initiation with ICS. Grace told me that ICS explained British volunteers’ presence in Kenya as a positive thing because where they go, the money and knowledge follow. What this did for Grace was ‘communicate the superiority and inferiority message long before they even meet’. Grace also quickly came to the realisation that the Kenyan volunteers generally had the upper hand in age, experience, and educational qualifications over the British volunteers. So, the ICS programme provided a mixture of contradicting messages, symbolism and realities for these two Kenyan volunteers. But overall, based on their reflections, I believe we can learn that ICS as a volunteer programme reinforced stereotypes about Whiteness. Paradoxically, the fact that ultimately Grace and Elijah recognised that what they were being led to believe both by ICS and broader society about Whiteness was not true could by itself be interpreted as a successful challenge to oppressive global power dynamics. However, as Grace mentioned, volunteers and local people experiencing our presence as young, white people assuming the ‘roles of ‘expert’ or ‘teacher’, despite our lack of experience, helped perpetuate unequal power relations and ideas of superiority (Raymond & Hall, 2008, p. 531), which is not conducive with a project that claims to be a ‘force for good’ which ‘tackles global challenges’ (ICSd, n.d.).

Conclusion

A postcolonial framework has been used to analyse both ICS, and the perspective of former volunteers and the conclusion will summarise the highlights of my research. ICS presented themselves overwhelmingly as a ‘responsible’ volunteer abroad programme with a positive impact, separating themselves from ‘poorly-managed projects’ (ISCb, n.d). But as shown, it was crucial to test this claim against the extent to which ICS addressed global inequality, global power structures and a history of colonialism. Based on my net-archival research and my interviews with former volunteers, clearly an apolitical and dehistoricised approach to global inequality was taken by ICS. After analysing the attitude of the government towards global inequality, we can begin to understand one factor that shaped the narrow view ICS took on inequality and development. In order to avoid controversy or self-reflection on the role the British Empire played and the role Britain continues to play in global inequality and power structures today, the UK government tends to focus on more palatable approaches to inequality, such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals and explanations framing poverty as ‘spontaneously occurring’ (Griffiths, 2017, pp. 339, 406). ICS did not encourage historical and critical engagement with the social issues supposedly at the heart of their projects, and in doing so, the organisation has encouraged thousands of young British people to remain uncritical about global inequality and poverty, which only serves to deepen further the issues ICS claimed to address.

It has also been shown, based on ICS material and the experience of the volunteers, that the volunteer selection process did not prioritise skills or experience to ensure the most efficient work could be carried out. Most volunteers confirmed that they did not feel they possessed the skill necessary to carry out placement activities to an effective level, and the British volunteers felt they were relatively inexperienced and unequipped in comparison to the Kenyan volunteers. It was remarked that Whiteness carries a symbolic level of superiority in Kenya, which was supported both by the experience of the British volunteers and the words of the Kenyan volunteers. By sending young, unskilled British volunteers to work in Kenya, ICS communicated the message that white people’s enthusiasm and interest alone qualify them to travel to the Global South, become involved in a community they know little to nothing about, and inappropriately assume roles they are not qualified for (Raymond & Hall, 2008, p. 531). Therefore, the construction of Whiteness as the standard to follow and the norm (Gabay, 2018) was reinforced by ICS.

Another crucial conclusion to be drawn from the ICS material and the experience of the volunteers is the tendency of the volunteer programme to treat the Global South as a space for young British volunteers to train and develop professionally and personally (Raymond & Hall, 2008, p. 539). Throughout ICS marketing and reports, the experience and development of the volunteer are given great focus, going as far as to describe the experience as an opportunity to ‘build the confidence necessary to achieve their personal and professional goals in later life’ (DfID & Mitchell, 2012). The volunteers echoed this finding, with some claiming that their motivation to volunteer with ICS included gaining experience to begin a career in development while also reflecting on the feeling that they took more benefits away from the experience than they could provide to the communities. From a postcolonial perspective, this process can be likened to the social and cultural exploitation of colonies by colonial powers, looting them of their knowledge, experiences and resources and denying them an equal exchange (Rodney, 1981).

Therefore, in light of my findings, as a volunteer abroad programme that partners British and in-country youth volunteers, ICS did not effectively challenge unequal power dynamics between the Global North and Global South, which find much of their origins in colonialism (Raymond & Hall, 2008). In doing so, ICS played an essential role in perpetuating neo-colonial relations and a British ‘colonial approach’ (Toomey, 2017, p. 153) to volunteering. My journey of self-reflection on this topic has been a long one and is constantly evolving and deepening. Like many other volunteers, I often feel shame when reflecting on my experience as a volunteer in Kenya. But what this has shown is that there needs to be more education and wider discussions in Britain around the impact of volunteer abroad programmes towards a decolonial end. Exactly how to conduct the most effective volunteer programmes and the extent to which they have a place in development is a very contentious issue that I cannot answer. However, what I have learnt is that first and foremost, any attempt to aid the development of communities in the Global South should be planned, led and controlled by the local community themselves, and any outside input must be on their terms. Every relationship and communication between the Global North and South can benefit from a critical postcolonial perspective because the continued impact of the legacy of colonialism in a mostly post-colonial world is significant and must be considered at every opportunity to avoid reproducing it and even towards rupturing neo-colonial dynamics and relations (Raymond & Hall, 2008; Toomey, 2017).

Bibliography

Ballie Smith, M. & Laurie, N. (2011). International Volunteering and Development: Global Citizenship and Neoliberal Professionalisation Today. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 36(4), 545-559.

Bell, D., Canham, H., Dutta, U. & Fernandez, J. S. (2019). Restrospective Autoethnographies: A Call for Decolonial Imaginings for the New University. Qualitative Inquiry, 26(7), 849-859.

Blichfeldt, B. (2007). What is ‘good’ anyway? The interviewing of acquaintances, Aalborg University.

Cameron, D. (2011 June 11). Why we’re right to ringfence the aid budget. The Observer.

DfID & Mitchell, A. (2012). International Citizen Service: Young people fight poverty. [Online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/international-citizen-service-young-people-fight-poverty [Accessed 26 November 2021].

Edwards, J. (2021). Ethical Autoethnography: Is it Possible. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, Volume 20.

Elliott-Cooper, A. (2021). Black Resistance to British Policing. Manchester University Press.

Ellis, C., Adam, T. & Bochner, A. (2011). Autoethnography: An Overview. Historical Social Research, 36(4), 273-290.

Emerson, R. (1969). Colonialism. Journal of Contemporary History, 4(1), 3-16.

Faleiro, E. (2013). Colonial, Neo-Colonialism and Beyond. The Journal of International Issues, 16(4), 12-17.

Gabay, C. (2018). Imaging Africa. Cambridge University Press.

Garland, E. (2012). How Should Anthropologists Be Thinking About Volunteer Tourism? Practicising Anthropology, 34(3), 5-9.

Garton, S. & Copland, F. (2010). ‘I like this interview; I get cake and cats!’: The effect of prior relationships on interview talk. Qualitative Research, 10(5), 533-551.

Griffiths, M. (2017). ‘It’s all bollocks!’ and other critical standpoints on the UK Government’s vision of global citizenship. Identities, 24(4), 398-416.

Heldke, L. (2001). ”Let’s Eat Chinese!”: Reflections on Cultural Food Colonialism. Gastronomica, 1(2), 76-79.

Hickel, J. (2013). The ‘Real Experience’ industry: Student development projects and the depoliticisation of poverty. The International Journal of Higher Education in the Social Sciences, 6(2), 11-32.

ICS (2020). ICS Report: 2011-2020, International Citizen Service.

ICSa (n.d.) About ICS. [Online] Available at: https://www.volunteerics.org/about-ics [Accessed 10 February 2022].

ICSb (n.d.) Responsible Volunteering. [Online] Available at: https://www.volunteerics.org/responsible-volunteering [Accessed 17 February 2022].

ICSc (n.d.) Our approach to anti-racism. [Online] Available at: https://www.volunteerics.org/what-we-stand-for/anti-racism [Accessed 9 February 2022].

ICSd (n.d.) Challenge yourself to change the world. [Online] Available at: https://www.volunteerics.org/ [Accessed 21 March 2022].

Klay Kieh, G. (2009). Reconstituting the Neo-colonial State in Africa. Journal of Third World Studies, 26(1), 41-55.

Loomba, A. (2015). Colonialism/Postcolonialism. Routledge.

Martin, G. (1982). Africa and the Ideology of Eurafrica Neo-Colonialism or Pan-Africanism? The Journal of Modern African Studies, 20(2), 221-238.

Mezbourian, A. (2017). Fighting discrimination against deaf children in Kenya. [Online] Available at: https://www.volunteerics.org/blogs/fighting-discrimination-against-deaf-children-kenya?_ga=2.241246274.1967839505.1644076748-473590331.1637594359 [Accessed 2 March 2022].

Owton, H. & Allen-Collison, J. (2013). Close but not too close: friendship as method(ology) in ethnographic research encounters. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 43(3).

Paul Gee, J. (2010). An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method. Routledge.

Raymond, E. & Hall, C. (2008). The Development of Cross-Cultural (Mis)Understanding Through Volunteer Tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(5), 530-543.

Rodney, W. (1981). How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Howard University Press.

Roiha, A. & Iikkakenen, P. (2022). The salience of a prior relationship between researcher and participant: Reflecting on acquaintance interviews. Research in Applied Linguistics, 1(1).

Simpson, K. (2004). ‘Doing development’: The gap year, volunteer-tourists and a popular practice of development. Journal of International Development, 16(5), 681-692.

Taylor, J. (2011). The Intimate Insider: Negotiating the Ethics of Friendship When Doing Insider Research. Qualitative Research, 11(1), 3-22.

Taylor, L. (2019). Debunking 4 myths behind youth volunteering, International Citizen Service.

Toomey, N. (2017). Humanitarians of Tinder: Constructing Whiteness and Consuming the Other. Critical Ethnic Studies, 3(2), 151-172.

V. S. O. (2021). Helping young mothers return to education. [Online] Available at: https://www.vsointernational.org/news/blog/helping-mothers-return-to-education [Accessed 10 October 2021].

VSO (2021). VSO Annual Report and Accounts 2020-2021, Voluntary Services Overseas.

VSOa (n.d.) Youth Volunteering (ICS). [Online] Available at: https://www.vsointernational.org/volunteering/youth [Accessed 21 January 2022].

VSOb (n.d.) History. [Online] Available at: https://www.vsointernational.org/about/our-history [Accessed 12 February 2022].

VSOc (n.d.) Volunteer with VSO. [Online] Available at: https://www.vsointernational.org/volunteering [Accessed 5 December 2021].

V. S. O. (n.d.) Ensuring Deaf young people aren’t excluded from sexual and reproductive health services. [Online] Available at: https://www.vsointernational.org/our-work/healthy-communities/inclusive-srhr/imbere-heza [Accessed 9 October 2021].

Young, R. (2016). Postcolonialism: An Historical Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Citizenship Deprivation Policy in the UK and Abroad: a Postcolonial Analysis

- China in Africa: A Form of Neo-Colonialism?

- Queer Asylum Seekers as a Threat to the State: An Analysis of UK Border Controls

- Do Colonialism and Slavery Belong to the Past? The Racial Politics of COVID-19

- “Fake It Till You Make It?” Post-Coloniality and Consumer Culture in Africa

- Safeguarding a Woman’s Right to Education and Water in Africa