Since the 1990s, there has been no shortage of academic interest in how indigenous civil society organisations (CSOs) influence post-conflict peacebuilding operations. Many studies have been carried out across social and political science, with varied objectives. Some question whether CSOs help to build a sustainable peace, with focus usually on a specific case study. Others investigate the relations between CSOs and members of the international community who are involved in a particular conflict. Some even question if they are a disruptive force, capable of preventing peacebuilding from being carried out. The differing aims of these studies means the literature can be difficult to navigate, not helped by scholars’ somewhat vague definitions of what ‘civil society’ is and what it represents. In this article, I attempt to make sense of this wide-ranging literature, by arguing that scholars in fact usually pivot their research around one of two interpretations of how indigenous CSOs influence peacebuilding. I define these as: (i) ‘problem-solvers’ who operationalise and legitimise a country’s peacebuilding efforts, and (ii) ‘autonomous political activists’ who publicly question and resist peacebuilding operations whilst advocating for what they believe peacebuilding should consist of.

Defining peacebuilding and civil society

It is firstly helpful to briefly establish what is meant by ‘peacebuilding’ and ‘civil society’, before delving into the article’s main objective. Although peacebuilding is often presented as an elusive term which ‘defies a single definition’ (Tschirgi 2013: 197) and is ‘difficult to define’ (Ryan 2013: 31), owing to the range of methods and approaches advocated for it to succeed, there is at least consensus that it is intended to address and tackle underlying structures and root causes of conflict. This is how John Galtung perceived it when he introduced the concept in a 1975 essay. He proposed that peace consists of the abolition of structural violence and the causes of war, such as oppression and domination, just as much as it is about eliminating direct violence or warfare (Galtung 1975). He argued that peace cannot succeed when antagonists are isolated and separated from one another, as it requires increased interaction channels between all levels of society, including a ’high level of interdependence’ and exchange between nations (Galtung 1975: 298-9). These ideas of association and interdependence are reflected in peacebuilding practices, where there is an emphasis on negotiation and dialogue-based initiatives.

Within the peacebuilding literature, civil society is usually defined as a sphere of voluntary collective action, comprising of ’shared interests, purposes and values’, distinct from the state, family and market (Paffenholz 2013: 351). Indigenously based organisations are typically presented as those founded and sustained by local stakeholders, with examples including faith-based organisations, social and political movements, and trade unions (Krznaric 1999: 8; Nilsson 2012: 249; Paffenholz 2013: 352). However, the usual definition of civil society can only take us so far. For one, we cannot easily draw distinctions between the state, family and market, given the boundaries will always be blurred and complex. This is particularly so in conflict settings where political authority is often fractured, and responsibilities are not clearly demarcated. However, the more fundamental point I wish to dwell on in this article is that it also does not help us to understand how interpretations of the function and purpose of civil society, and more specifically individual CSOs, widely differ when it comes to evaluating their impact upon peacebuilding.

Problem-solving interpretation

This first interpretation refers to the idea that CSOs can operationalise and legitimise a country’s peacebuilding efforts, helping them to succeed in the long term. It is a belief that became particularly salient during the aftermath of the failed peacebuilding missions of the 1990s, when the field became synonymous with ‘liberal internationalism’. This ideology was inspired by the United Nation’s 1992 Agenda for Peace report, which stipulated that ‘democracy at all levels is essential to attain peace for a new era of prosperity and justice’ (Boutros-Ghali 1992: para.82). The international community was subsequently ruled by the idea that peace could only be ordained if democratic elections, marketisation programs and constitutional reforms codifying civil rights were established in areas of conflict. However, this paradigm was quickly deemed ineffective and unsuccessful in establishing peace, not least because war-torn societies do not tend to possess the required infrastructure, socio-economic stability or political will to embark on elections (Paris 1997: 57; Kumar 1998: 7). Indeed, this one size fits all approach to peacebuilding, consisting of imposing Western ideals of market democracy onto radically different countries decimated by conflict, was soon regarded as naïve and unrealistic.

Consequently, there was a general sense that alternative approaches to peacebuilding were required. One such alternative, termed the social constructivist approach, advances that peace does not have a universally accepted definition, given that it means ‘different things to different actors in different contexts’ (Wallis 2021: 77). Therefore, rather than peace being imposed onto a particular setting, the belief is that it should be based on the ideas and practices of human agents within intersubjective social contexts. In other words, creating a durable peace is contingent upon the input of indigenous and contextual knowledge. Such an approach is reflected in a body of literature termed the ‘local turn’, which emphasises the active involvement of people on the ground in peacebuilding efforts (Leonardsson & Rudd, 2015: 825; Odendaal, 2021: 627). Most of these studies begin by citing John Paul Lederach. In his 1997 ‘integrated framework for peacebuilding’, Lederach taught that sustainable peace is rooted in local people, who must become drivers of peacebuilding efforts if peace is to be ordained. This is said to only be possible through ‘clearer channels of communication’ and integration between all levels of society, including the grassroots and the external actors who are involved in a particular conflict (Lederach, 1997: 100).

Given this increased focus on building peace from the grassroots level, theorists and practitioners commonly perceive indigenous CSOs as indispensable to successful and long-lasting peace. The inclusion of civil society is discussed as a silver bullet to overcoming problems associated with external actors imposing their own version of peace onto communities and societies they are unfamiliar with. This is because CSOs – with women’s organisations, religious associations and groups dedicated to human rights being amongst those often mentioned – can help peacebuilding efforts to ’gain broader public legitimacy and in turn become more durable’ (McKeon, 2004), given that they are in touch with citizens on the ground and have a deep awareness of a conflict’s internal dynamics and developments. A related assumption is that civil society is embedded with values of civility, tolerance, cooperation, non-violence and transparency – all deemed essential to resolving persistent disputes and tensions.

These beliefs are reflected in the international community’s assessments for why CSOs need to become actively involved in peacebuilding. The United Nations (UN) claims that ‘real progress’ depends upon accessing their knowledge and resources, besides ‘actively including them in their work’ (United Nations Security Council, 2015: 14). The European Union (EU) has spoken of how an ’empowered civil society is a crucial component of any democratic system’ and is an ‘important player in fostering peace’ (European Commission, 2012: 3). These claims are supported by a wealth of academic research which has sought to empirically test the extent to which the inclusion of CSOs does mean peace and is more likely to prevail in the long term. Desiree Nilsson’s quantitative study assessed 83 peace agreements signed between 1989 and 2004, determining that CSO involvement is beneficial to the durability of peace (Nilsson, 2012: 246). Similarly, Roberto Belloni argues that including civil society in the Bosnian peace process is vital for its ‘long-term sustainability’ (Belloni, 2001: 164), whilst David Roberts claims that ’indigenous organisations’ are vital to creating a ’meaningful, stable and viable’ peace in Cambodia (Roberts, 2008: 67).

In terms of how local CSOs can practically influence peacebuilding operations and thereby fulfil a problem-solving function, focus is generally placed on their role as facilitators of Track II (T2) initiatives: unofficial and informal activities, such as inter-ethnic dialogue sessions and workshops, designed to enhance interaction and understanding between disputant parties. They are intended to complement Track I diplomacy, or official negotiations and peace talks carried out by diplomats (Mapendere, 2000: 67). T2 efforts help to stimulate a ‘peace constituency’ by emphasising the value of peaceful relations and building trust between disputants (Burgess & Burgess, 2010: 16), thereby creating conditions where official peace negotiations and strategies are more likely to succeed. Indigenous CSOs are considered particularly effective in facilitating them. They are generally trusted by conflicting parties, who regard their aims as more legitimate and genuine than those of official actors. Consequently, CSOs can access a greater number of communities than officials whose lack of knowledge of a conflict’s complex internal politics can be a barrier to engaging with disputants (McKeon, 2005: 3-4). It should be noted, however, that indigenous CSOs are diverse in their objectives and actions, so some are better suited to peacebuilding than others. Faith-based organisations are believed to be particularly effective, owing to their experience as educators and intermediaries (Bercovitch & Kadayifci-Orellana, 2009: 176).

Autonomous political activist interpretation

The underlying issue with the problem-solving idea is that it assumes CSOs, perhaps owing to their supposed in-built civility and tolerance, passively support and help to enact a country’s peacebuilding operations without possessing their own views or preferred agenda. In contrast, the ‘autonomous political activism’ interpretation focuses on indigenous CSOs publicly challenging and resisting peacebuilding efforts, in addition to advocating which root causes of conflict should be focused upon. CSOs are therefore seen as having the autonomy and agency to exist outside of any other actor’s sphere of influence and as being more than just peacebuilding legitimisers and facilitators. Indeed, they can cause rather than solve problems for external peacebuilders, notably members of the international community.

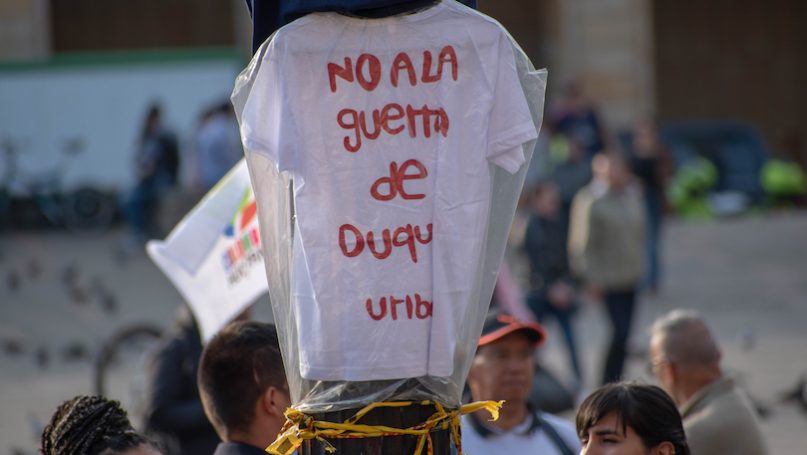

Academic studies have focused on how CSOs resist and refuse to comply with peacebuilding initiatives driven by external actors. They tend to focus on overt and symbolic forms of resistance, such as riots, demonstrations, boycotts and media campaigns (Mac Ginty, 2012: 178; Galvanek, 2013: 12). These actions can be planned or spontaneous. They are typically initiated by CSOs and rely upon a collective force of action. One example refers to the Cypriot conflict, where the ‘Green Line Regulation’ was introduced in 2004 to allow goods on either side of the divided country to be exported to the other. The EU hoped the regulation would foster economic cooperation and integration between both sides. However, it did not have its intended consequences, due to CSOs in the Greek Cypriot south of the island rejecting and boycotting goods from the Turkish Cypriot north. Businesses refused to sell Turkish Cypriot products whilst newspapers refused to advertise them (Galvanek, 2013: 74). Resistance activities can also be covert and more subtle, sometimes referred to as ’everyday resistance’ (Ejdus & Juncos, 2018: 17), or ‘non-participation’ (Mac Ginty, 2012: 167). This revolves around CSOs encouraging wider society to not participate or engage in political processes, such as elections, and to generally exert passivity towards peacebuilding programs which are believed to be ’incompatible with their perceptions and daily practice for sustaining their livelihood’ (Lee, 2021: 601). These actions can nonetheless have significant effects and have been equated with ’guerrilla warfare’ (Scott, 1989: 49).

In addition to resisting or not complying with external peace operations, some studies have specifically looked at how CSOs directly undermine them through disseminating defamatory, instigative messages, or by acting in a threatening and divisive manner – practices that have contributed to the conceptualisation of an ‘uncivil society’. Camilla Orjuela’s study into peacebuilding in Sri Lanka is a case in point. She outlines how Sri Lanka’s ethnic polarisation has contributed to the growth of local militant organisations, centred upon ethnic and ’racist lines’ (Orjuela, 2003: 204). They discourage individuals from participating in peace activities which they regard with suspicion. It leads to a situation ‘where even the idea of civil society cannot be taken for granted’ (Orjuela, 2003: 198), as the reality is far removed from the idealised version of civil society often portrayed in the literature. Roman Krznaric’s research into the Guatemalan peace process found that civil and ‘uncivil’ actors both exist within conflict settings. He analysed one civil and one uncivil association to highlight the differences between them, with the uncivil actor’s support of non-democratic politics and its attempts to ‘limit citizenship rights’ being down to its motivation ’to preserve economic privileges’ (Krznaric, 1999: 7). As discussed earlier, many theorists and practitioners associate CSOs with notions of civility, tolerance and non-violence. However, this assumption can clearly cause empirical problems if researchers are not expecting conflict settings to comprise of a complex mixture of civil and uncivil organisations.

A further aspect of the autonomous political activism interpretation centres on CSOs advocating and proposing their own ideas for how peacebuilding efforts should be implemented and what they should entail. In their typology of the different functions carried out by civil society in the peacebuilding domain, Thania Paffenholz and Christoph Spurk reveal how advocacy and public communication is widespread amongst CSOs in a range of conflict settings, through them ‘articulating interests’ and creating ‘channels of communication to bring them to the public agenda’ (Paffenholz & Spurk, 2006: 13). Such examples include bringing specific conflict-related themes, such as legal issues around the recognition of individual rights, to the national agenda through lobbying activities, and campaigning for civil society to be involved in peace negotiations (Paffenholz, 2010: 386). This can involve applying pressure to foreign governments and IOs, a tactic described as the ‘boomerang effect’, given CSOs bypass their own state institutions by appealing to international actors who can publicly support their agenda from ‘the outside’ (Keck & Sikkink, 1998: 12).

However, there are of course numerous factors that can ‘reduce the space for civil society to act or influence its effectiveness’ (Paffenholz, 2010: 404). In certain conflict settings, they may be unable to act in the way I have described. One of the predominant factors to consider is the behaviour and intentions of the state, or political authority, which governs the area where CSOs are based. In some circumstances, political authorities may be repressive and controlling of civil society, thereby reducing its autonomy and freedom to play a politically active role. The level of division and insecurity within a society is also highly significant. If there is widespread fear and distrust, perhaps due to ethnic or religious tensions, CSOs may not be able to safely promote peacebuilding. There are certainly some cases where those ’advocating publicly for peace have become targets’ to violent groups (Paffenholz, 2010: 410). Another important point is the effect that international donors can have upon the initiatives of indigenous CSOs. There is a wide disparity as to how dependent they are upon funding. However, for some recipients it is their primary source of income, to the extent that they would not be able to organise their activities without it. For these groups, the funding may influence how politically active they choose to be, besides indirectly determining their peacebuilding ideology.

Conclusion

The objective of this article has been to outline how indigenous CSOs impact peacebuilding efforts. Although there is widespread academic attention on this topic, the literature can prove somewhat overwhelming. Studies have conflicting aims and typically struggle to articulate how there are contrasting interpretations as to civil society’s role in peacebuilding. I have attempted to make sense of this, by demonstrating how the literature largely revolves around two interpretations. The first, defined as ‘problem solving’, regards CSOs as legitimisers who can operationalise peacebuilding, in part by alleviating problems associated with external, international actors attempting to intervene in a conflict where they lack deep connections or understanding. CSOs’ involvement typically comes through coordinating T2 initiatives, including workshops and dialogue-based activities. However, the issue with this interpretation is that it assumes CSOs passively support peacebuilding on the ground without raising their own views or agenda. This is where the ‘autonomous political activist’ interpretation is relevant, as it contends that CSOs do have a life of their own. They resist and challenge peacebuilding operations and advocate alternative areas of focus – actions which can cause problems for the international community involved in a particular conflict. In categorising CSOs this way, I am not claiming that only one or the other interpretation can be present in specific conflict settings. On the contrary, the picture is incredibly complex in practice, with individual CSOs more likely to perform each role at different times, rather than be constrained to being just a problem-solver or autonomous activist. Nonetheless, these two interpretations help us to understand the contrasting ways in which researchers and policymakers evaluate the impact of indigenous CSOs upon peacebuilding.

Bibliography

Belloni, Roberto. 2012. ‘’Hybrid peace governance: Its emergence and significance’’. Global Governance 18, No. 1: 21–38.

Bercovitch, Jacob and Ayse Kadayifci-Orellana. 2009. ‘’Religion and mediation: The role of faith-based actors in international conflict resolution’’. International Negotiation 14, No. 1: 175-204.

Boutros-Ghali, Boutros. 1992. ‘’An Agenda for Peace: Preventive Diplomacy, Peacemaking and Peace-keeping’’. UN Department of Public Information: New York. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/145749.

Burgess, Heidi and Guy Burgess. 2010. ‘’Conducting track II peacemaking’’. US Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/resources/PMT_Burgess_Conducting_TrackII.pdf.

Ejdus, Filip and Ana E Juncos. 2018. ‘’Reclaiming the local in EU peacebuilding: Effectiveness, ownership, and resistance’’. Contemporary Security Policy 39, No. 1: 4-27.

European Commission. 2012. ‘’Communication from the commission to the European parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions: Europe’s engagement with civil society in external relations’’. Publications Office of the European Union. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/9ee46839-55ef-4120-bb8d-e39b3640d53d/language-en/format-PDF.

Galtung, Johan. 1975. ‘’Three approaches to peace: Peacekeeping, peacemaking, and peacebuilding’’. In Peace, War and Defense – Essays in Peace Research, edited by Johan Galtung, 282-304. Copenhagen: Christian Ejlers.

Galvanek, B Janel. 2013. ‘’Translating peacebuilding rationalities into practice: Local agency and everyday resistance’’. Berghof Foundation. file:///C:/Users/hiu61/Downloads/Translating%20Peacebuilding%20Rationalities%20into%20Practice.pdf.

Jewett, Georgia. 2019. ‘’Necessary but insufficient: civil society in international mediation’’. International Negotiation 24, No. 1: 117-135.

Kaldor, Mary. 2003. Global Civil Society: An Answer to War. Somerset: Polity Press.

Keck, E Margaret and Kathryn Sikkink. 1998. Activists beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics. New York: Cornell University Press.

Krznaric, Roman. 1999. ‘’Civil and uncivil actors in the Guatemalan peace process’’. Bulletin of Latin American Research 18, No. 1: 1-16.

Kumar, Krishna. 1998. Postconflict Elections, Democracy and International Assistance. Colorado: Lynne Rienner.

Lederach, John Paul. 1997. Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press.

Leonardsson, Hanna and Gustav Rudd. 2015. ‘’The ‘local turn’ in peacebuilding: a literature review of effective and emancipatory local peacebuilding’’. Third World Quarterly 36, No. 5: 825-839.

Mac Ginty, Roger. 2012. ‘’Between resistance and compliance: Non-participation and the liberal peace’’. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 6, No. 2: 167-187.

Mac Ginty, Roger. 2013. Routledge Handbook of Peacebuilding. London: Routledge.

Mapendere, Jeffrey. 2000. ‘’Track one and a half diplomacy and the complementarity of tracks’’. Culture of Peace Online Journal 2, No. 1: 66-81.

McKeon, Celia. 2004. ‘’Owning the process: The role of civil society in peace negotiations’’. Conciliation Resources. https://www.c-r.org/resource/owning-process-role-civil-society-peace-negotiations.

Nilsson, Desiree. 2012. ‘’Anchoring the peace: civil society actors in peace accords and durable peace’’. International Interactions 38, No. 2: 243-266.

Odendaal, Andries, 2021. ‘’Local Infrastructures for Peace’’. In The Oxford Handbook of Peacebuilding, Statebuilding, and Peace Formation, edited by Oliver P. Richmond and Gëzim Visoka, 627-640. Oxford University Press.

Orjuela, Camilla. 2003. ‘’Building peace in Sri Lanka: A role for civil society?’’. Journal of Peace Research 40, No. 2: 195-212.

Paffenholz, Thania and Christoph Spurk. 2006. ‘’Civil society, civic engagement, and peacebuilding’’. Social Development Papers: Conflict Prevention & Reconstruction. https://hakikatadalethafiza.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Pfaffenholz-Spunk-Civil-Society-Civic-Engagement-and-Peacebuilding.pdf.

Paffenholz, Thania. 2013. ‘’Civil Society’’. In Routledge Handbook of Peacebuilding, edited by Roger Mac Ginty, 347-359. London: Routledge.

Paffenholz, Thania. 2010. Civil Society & Peacebuilding: A Critical Assessment. Colorado: Lynne Rienner.

Paris, Roland. 1997. ‘’Peacebuilding and the limits of liberal internationalism’’. International Security 22, No. 2: 54–89.

Richmond P Oliver and Gezim Visoka. 2021. The Oxford Handbook of Peacebuilding, Statebuilding, and Peace Formation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Roberts, David. 2008. ‘’Hybrid polities and indigenous pluralities: Advanced lessons in statebuilding from Cambodia’’. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 2, No. 1: 63-86.

Ryan, Stephen. 2013. ‘’The Evolution of Peacebuilding’’. In Routledge Handbook of Peacebuilding, edited by Roger Mac Ginty, 25-35. London: Routledge.

Scott, C James. 1989. ‘’Everyday forms of resistance’’. Copenhagen Papers 4: 33–62.

Tschirgi, Necla. 2013. ‘’Securitisation and Peacebuilding’’. In Routledge Handbook of Peacebuilding, edited by Roger Mac Ginty, 197-210. London: Routledge.

UN Security Council. 2015. ‘’Report of the high-level independent panel on peace operations on uniting our strengths for peace: politics, partnership and people’’. United Nations General Assembly Security Council. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/N1518145.pdf.

Wallis, Joanne. 2021. ‘’The Social Construction of Peace’’. In The Oxford Handbook of Peacebuilding, Statebuilding, and Peace Formation, edited by Oliver P. Richmond and Gëzim Visoka, 77-90. Oxford University Press.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Civil Society Actors and the Challenge of Dark Heritage in Bosnia

- Civil Society and the Syrian Refugee Crisis

- Understanding Peacebuilding: An Issue of Approach Rather than Definition

- Developing Countries and UN Peacebuilding: Opportunities and Challenges

- Pluriversal Peacebuilding: Peace Beyond Epistemic and Ontological Violence

- What Determines The Implementation of Civil War Peace Agreements?