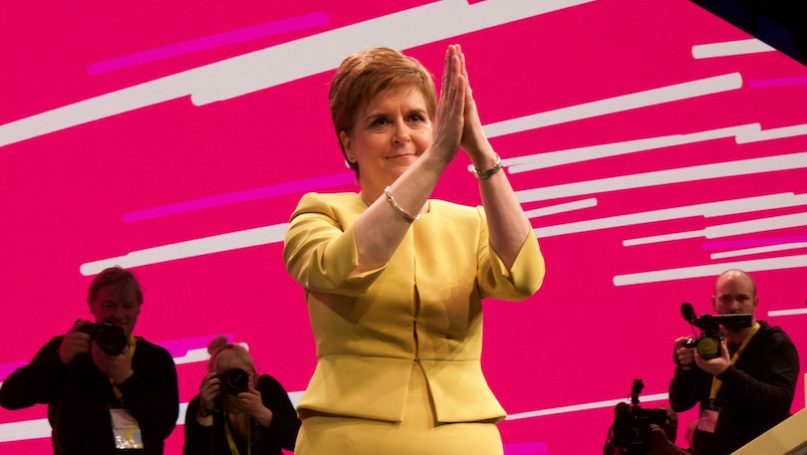

Nicola Sturgeon’s announcement that she will resign as First Minister of Scotland comes at a fractious time for Scotland’s independence debate. After the UK Supreme Court ruled the proposed October referendum this year to be illegal, the matter is likely to feature prominently in the next UK general election to be held in late 2024. Meanwhile, Scotland’s ability to craft its European framework in realistic terms remains distant, and it is unlikely that Scottish independence will become a reality anytime soon. For the Scottish National Party (SNP) this presents a clear policy and ideological dilemma for Sturgeon’s successor.

Already, the SNP’s Westminster leader Stephen Flynn has stated that ‘a major rethink’ may be needed regarding the party’s plans for a second referendum. The upcoming party conference in March will be key for SNP figures to outline their plans, not just regarding independence, but towards Scotland’s economy, controversial bills launched by Sturgeon such as the Gender Recognition Reform Bill, and relations with the governing Conservatives in Westminster. A major reset is likely in order, one that if implemented correctly, will ultimately benefit Scotland and its relations with both London and Brussels in the long term.

In 2014, Scotland’s independence debate took place in the pre-Brexit era in which Scotland’s place in Europe felt assured. Now, outside of the EU and framing independence as the only way in which to regain Scotland’s place within the bloc, Holyrood, like Westminster and other devolved parliaments, has been fixated on the intricacies of a result that few were expecting. For the SNP, Brexit revitalised an issue that formed the heart of their party platform, and with Sturgeon resigning, the SNP now has the chance to unequivocally state what they are for. Not just for Europe and a second independence referendum, but for the material conditions and policy proposals that would have a direct impact on their constituents’ lives.

This would allow any second referendum to occur under the best possible circumstances for all of Scotland’s political parties. The Scottish Conservatives, led by Douglas Ross, have long stated that the government should focus on issues that ‘really matter to people’ like pressures facing the NHS and the cost-of-living crisis in the UK. A focus on growth and economics outside of the independence framework can help better position Scotland within the UK, while charting a strong position for a second independence vote should the voters desire it.

Like most regions and constituent nations of the UK, Scotland’s identity and place in Europe has been severely tested by Brexit. Despite an undeniably strong connection to Europe, Scotland remains as ‘un-Europeanised as the rest of the UK’ according to a recent essay by a prominent Scottish political analyst. Furthermore, the essay states that with ‘a façade of pro-EU sentiment’, there remain ‘substantial disconnects’ between Scotland and the institutions and functioning of the EU. In addition, a report for the Scottish Parliament’s Constitution Committee found the Scottish government failed to keep Scottish legislation in line with hundreds of changes in EU law. This legal and legislative disconnect has not served Scottish voters and only provides a veneer of connectivity with Brussels while lacking the political will required to fundamentally transform Scotland’s relations with Europe.

After over a decade in power, a sense of complacency and perhaps inevitability has settled into the SNP’s thinking when it comes to independence. Few things are inevitable in politics, and the SNP risks sapping the agency from their party members and fellow Scots, rewarding authority and identity in confrontation with the rest of the UK over an enlightened and principled sense of autonomy.

Sturgeon’s resignation marks the first time in many years in which Scotland can recalibrate its approach and combine lofty, ideological rhetoric with practical policy proposals. Westminster has long been an easy scapegoat, and it remains politically convenient for the SNP to criticise the Conservatives who allegedly caused the mess rather than it is to devise pragmatic solutions. Thus far, Prime Minister Sunak has shown a greater willingness than his predecessors to work productively on sensitive Brexit-related issues. This includes renewed diplomacy over the Northern Ireland Protocol with Brussels, signalling reasons to be optimistic that Sunak can form a positive working relationship with Sturgeon’s successor.

However, for a second Scottish independence referendum to be remotely viable in the next decade, substantive input from additional Scottish parties like Labour and the Conservatives, formal legal approval from London, and sustained coordination between Holyrood and Brussels on EU policies will have to be met. In the interim, Scotland has many gifts it can still bring to its relationship with the UK. Scotland should be proud to be a constituent nation of a state that can still play a vital role in Europe as witnessed in London’s support for Ukraine, as well as in upholding the liberal, rules-based international order with the United States and other allies. Scotland can remain outward-looking towards continental Europe while fortifying its relations closer to home.

In looking to the future, Sturgeon’s successor would be wise to portray independence as an organic outcome from a yet-to-be-defined stage in Scotland’s political development. This would be in sharp contrast to Sturgeon’s view of independence as an organising principle or an endgame that pillories the opposing side while placing Scottish politics in a straitjacket. In short, independence should be temporarily freed from the shackles of government, only so that when it returns to the political calculus it can exist in a truer form that is more fully reflective of the people of Scotland.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Scottish Foreign Policy in the Brexit Era

- Opinion – Scotland: Host of COP26 but Divided on Its Role in the World

- Opinion – Brexit and Its Many Identities in the UK

- Opinion – The Rohingya Conundrum amid the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Opinion – Brexit and the Continued Troubles in Northern Ireland

- Opinion – The UK’s Complicated and Contradictory COVID-19 Moment